Relocating “Stuffed” Animals

Photographic Remediation of Natural History Taxidermy

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.9991

Stephanie S. Turner writes about extinction and animal representation in scientific and popular texts. She is currently co-curating an exhibit, “Animal Skins, Visual Surfaces,” at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, where she teaches science communication.

Email: turnerss@uwec.edu

Humanimalia 4.2 (Spring 2013)

Abstract

This essay focuses on the remediating effects of photography of natural history museum taxidermy. How do these works refigure the apparent verisimilitude of taxidermied animals and their realistic diorama “habitats”? And how do they implicate viewers? Applying historian and curator Rachel Poliquin’s typology of taxidermy to a number of examples, I show how the “talkative thingness” of taxidermied animals — their tendency to signify in excess of their materiality — is expressed in the overlapping descriptive, biographical, cautionary, and experiential aspects of a number of contemporary photographers of natural history museum taxidermies.

From the Natural History Museum to the Art Gallery: Taxidermic Aesthetics

The decades-old taxidermies of the natural history museum’s golden era of dioramas are beginning to show their age, and many curators are now faced with some tough decisions about whether to refurbish the taxidermied animals and their fading diorama “habitats,” auction them off, or even destroy them (Poliquin 123-124; Milgrom 160-190). As Merle Patchett observes, other curators of these “uncomfortable reminders” of colonialism have shifted them from display to storage, removing them from public view yet maintaining them in museum archives (“Putting” 12). Meanwhile, outside the natural history museum, taxidermy as an art form (hunting trophies aside) has been flourishing (Connor). This trend in “dead animal art,”1 which can be traced as far back as Robert Rauschenberg’s famous tire-and-goat taxidermy Monogram (1959), is evident in the work of such contemporary mixed-media artists as Damien Hirst, Mark Dion, and Polly Morgan. Many of these artists do more than merely incorporate the bodies of dead animals into their works; mastering the art of taxidermy themselves, some of them create their own mounts, mixing and matching animal parts and incorporating other objects into their artwork. By relocating taxidermied animals from natural history museums to art museums and galleries, these artists are also dislocating them from familiar natural history classification systems and established genres of natural history museum exhibition. Out of context, the animal objects thus lose some of their aura as scientific artifacts as they gain an aura of objects d’art.

One result has been a shift in the discussion of authenticity in animal representation that has been so central to natural history taxidermy (Quinn). New ontological questions arise: how does the “realness” of a taxidermied animal in the art museum differ from its “realness” in the natural history museum? What sort of difference does the dead animal object make in this new space? Mark Dion’s installation Mobile Wilderness Unit — Wolf (2006) (Fig. 1) illustrates the irony that can result from such relocation. Cropping a diorama that features a single wolf standing next to a rock to fit on a small trailer, ready to be pulled along by a vehicle, the installation mockingly calls attention to the problem of verisimilitude of the taxidermy-in-a-diorama genre. Such displays are fleeting, the installation suggests; their easy relocation as objects disconnects them from the actual living things they stand for. Yet another layer of irony here, though, is that for Dion’s installation to work, it must still “look real.” The discussion of verisimilitude in taxidermy representation is also therefore epistemological: what new meanings might the relocated and remediated dead animal object—together with the new target audience — create? What more can the viewer come to know about, say, humans’ relationship with wolves and their habitat from looking at Dion’s installation? Artwork incorporating taxidermy jars the viewer’s sensibility of what dead animal objects represent, and where and how they should be displayed. Taxidermied animals displayed deliberately out of place or, in Steve Baker’s formulation, “botched” in some way, call upon the viewer to rethink human relationships with animal others or, at the very least, ponder “what it is to be human now” (Baker, The Postmodern Animal 54).

Figure 1: Mark Dion, Mobile Wilderness Unit — Wolf, 2006, Courtesy George Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna. Photo Lisa Rastl.

Cultural studies of artwork about taxidermy have affirmed these forms of animal representation as endemic to the larger field of animal studies. For example, Ron Broglio, in Surface Encounters: Thinking with Animals and Art, explores how contemporary artists, including those working with taxidermy, are challenging the notion that animals “live on the surface of things” (xvi) because they are assumed to lack self-reflexivity. Whereas Broglio is concerned with the instantiation of animal corporeality in contemporary art — how an aesthetic encounter with animals opens up a shared space with the viewer — Giovanni Aloi is more concerned with the “deterritorialization” of animals in contemporary art (31-39) — how the current use of real animals in art signals a seismic shift in our “relational modes” with animal others (xv). Although Aloi, in his chapter on taxidermy art, does mention photographic images of natural history taxidermy as “shattering the illusory aura of the diorama” (28-31), no systematic examination of photography of taxidermy in situ — photographs made within the natural history museum that are meant to be viewed in spaces dedicated to artistic practices — has been undertaken.

Scholarly interest in the cultural resonances of natural history taxidermy can be traced to Donna Haraway’s 1984 analysis of famed taxidermist Carl Akeley’s exhibits in New York’s Natural History Museum, created during the early twentieth century. Haraway’s critical reflection on the ideological value that natural history taxidermy once held in gaining popular support for imperialist projects, along with its role in the development of museum exhibits, has been treated at length (see, for example, Asma; Patchett, “Putting”). Central to any close examination of taxidermy’s role in animal representation is the fascination it holds as a craft and creative process, how taxidermy, as a material practice, makes dead things life-like. Art historian Rachel Poliquin observes in The Breathless Zoo that taxidermy, “straddling the nature-culture opposition [...] requires its own aesthetic vocabulary” (107). Art critic Steven Connor, too, indicates a unique aesthetic surrounding taxidermy, one that, significantly for my analysis of taxidermy photography, is linked to its historical function as a predecessor to photographic documentation: “the art of taxidermy is an art that conceals art,” Connor writes, “which aims to create something like a photographic sculpture of the animal” (3; see also Poliquin, Breathless 50).

A natural history museum taxidermy presented as art confronts viewers anew with its construction as a cultural thing. In this aestheticized object, its historical lived reality is both erased and recreated in the object’s carefully crafted pose and the drama of its display. At the same time, however, as a work of art, the taxidermy calls for additional layers of perception: first it calls attention to itself as something created, something with a different kind of material reality than the thing it represents; then it asks the viewer to consider the significance of its relocation from its usual “habitat.” Indeed, it is as if the aestheticized taxidermied animal has assumed a sort of agency. While still “real enough” to reference the actual animal, and perhaps, as well, its former surroundings, taxidermy in the art museum references a great many other cultural “habitats” — historical, social, geographical, ideological — that the animal and the viewer not only occupy together but also co-constitute. One example of such co-constitution is another well-known work by Dion, Tar and Feathers (1996) (Fig. 2). This installation uses the tarred and feathered bodies of animals often considered “pests” (rats, cats, snakes, and crows) to reference the tarred and feathered bodies of black lynching victims, who were dehumanized in their treatment as slaves. The taxidermied animal as art object creates meanings beyond what it signifies as a representative type specimen. By exposing its cultural history and continuing significance, taxidermy art tends to reveal very little to the viewer about the actual animal whose skin it wears but suggests quite a lot about the circumstances that brought it to this place and create around it a new meaning.

Figure 2: Mark Dion, Tar and Feathers, 1996, Mixed media, courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

In her essay “The Matter and Meaning of Museum Taxidermy,” Poliquin describes this suggestiveness of taxidermy as its “provocative loquaciousness,” the “talkative thingness” (125) of a once-living animal made to look alive and perhaps, too, anthropomorphized, as though it actually could talk back. This cultural thingness of the taxidermied animal proliferates when it is relocated to an art museum, raising not only the issues of the ethics of the post-colonial sourcing of the animals (Desmond), but also the culpability of the viewer’s consuming gaze within that visual economy (Baker, “‘You Kill Things’”). In other words, the viewer wonders, where did the animal bodies come from to make these things, and is it all right to look at them? Baker suggests that such is the “pressing reality” of the animal body in dead animal art that viewers are called to respond as though its agency as a living being persisted after its death (“‘You Kill Things’” 78). Part of this agency resides in the power the dead animal object has over the viewer to prompt a narrative imagining its (re)creation and (re)location. In the visual economy of taxidermy as art, the dead animal object invokes a consuming gaze that is both a product of our myriad relationships with non-human others as well as a reminder of the limits of those relationships. Despite the viewer’s elaborate imagining of the animal others in taxidermy art, the pressing materiality of the once-living skin of the individual animal constitutes a boundary to what we can know about the animals on display. Skin, therefore, is what mediates taxidermic aesthetics.

Many critics focus on the skin of the taxidermied animal — the only part of the animal that remains in a taxidermy, its residual “realness” — as a sort of permeable medium through which the viewer imagines a palpable connection with the animal other. According to art critic Rikke Hansen, skin, a border around our corporeal being that is a trait we share in common with other living things, becomes, in cultural terms, a kind of “unfinished project” in the Western effort to keep human and non-human animals separate (10-11), much like the dubious cultural purpose human skin has long served in otherizing groups within our own species. This project proceeds in ambivalent ways: we define our humanity, in part, by our prideful lack of a hairy hide or feathery covering, yet we take animals’ skins from them to cover and adorn our own; we kill animals for all kinds of reasons — including, as the artist Damien Hirst puts it, simply “to look at them” (qtd. in Baker, “‘You Kill Them’” 84) — then we recreate the dead animals from their skin so we can keep right on looking at them. In this sense, as Rachel Poliquin explores at length in The Breathless Zoo, the consuming gaze is also a longing gaze. We want more than just skin. Ron Broglio echoes Hansen’s argument about the “unfinished project” that is skin. Linking skin to surface, and surface to the “contact zone,” Broglio uses Mary Louise Pratt’s description of that social zone comprised of both peril and possibility in which unfamiliar others come into contact and negotiate their differences (Surface Encounters 93). Surface, then, is much more than just surface; it refers to the processes by which skin remediates.

From Animal Skin to Photographic Image: Proliferating Surfaces

One striking trend in the visual economy that taxidermy seems to proliferate is the photography of natural history taxidermy in situ. Increasingly, photographers have been making images of the taxidermies and dioramas in natural history museums. These images then make their way, in the flat surfaces of various lens-based media, into the art museum or gallery. Unlike the artistic relocation or recreation of the sculptural dead animal object in the art museum, which then occupies that space as a remanufactured, and in that sense revitalized, corporeal entity, the photograph of the dead animal object remediates its talkative thingness spectrally, through what Roland Barthes would describe as the “irreducible singularity” (Houlihan) of the frozen photographic image. In Barthes’s famous formulation, “what the Photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once: the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially” (Barthes 4). Barthes was moved to write his famous theory of photography in Camera Lucida after looking intently at a number of photographs of his recently dead mother. He was trying, as he put it, to locate her “essence” in the images (66). More than an act of mourning (Dillon), however, Barthes’s quest led him to the realization that the photographic image is distinct from other forms of representation in that it indexes a singular object in a particular moment of time. This indexing is much like the correspondence between a taxidermy and the living animal it represents (Henning 138). In other words, the photograph and the objects arrested in its image (as with the taxidermy and the animal it represents) are more proximate to each other than, say, the objects represented in a painting are to the actual objects. At the same time, however, the photograph, whether film or digital, is also a material thing,2 and the photographic surface adds a layer to the dead animal object held in the viewer’s gaze, effecting perhaps a “safe” distance from the materiality of the actual taxidermy. Further, this equivocal proximity, strangely enough, seems more apparent in older photographs, in photographs of old things, and in photographs that anticipate posterity (as in a photograph of an animal known to be critically endangered, or possibly already extinct). In this way, then, “every photograph” signals “the return of the dead” (Barthes 8). Given Barthes’s formulation of the nearness of the photographic image to the actual thing it shows, what are we to make of the unrepeatable existentiality of the photograph of the taxidermy, the dead animal object that is itself “something like a photographic sculpture” (Connor 3)? How does a photograph of a taxidermy mediate the “talkative thingness” of the actual thing (Poliquin 125)? Is it a difference in kind, of degree, or both?

Many of the photographers making images of natural history taxidermy — Diane Fox and Jason DeMarte, for example — emphasize the fabricated nature of their exhibition within dioramas. Referencing events and objects beyond the frame, including sometimes the viewers themselves, these photographs implicate viewers in some larger cultural narrative about animal representation and the consuming gaze. Other photographers working in this vein — Nicole Hatanaka, Danielle Van Ark, and Jules Greenberg — make images of taxidermied animals in museum storage rooms and work spaces, rendering these archival holding areas a different kind of exhibit space. Many of these photographers gesture toward a documentary genre, in effect creating a photographic archive of backroom collections. Other photographers of taxidermied animals in storage, however, — Sarah Cusimano Miles and Mary Frey — filter the images through more aesthetic modes, for example framing the subject as a still life or portrait, or manipulating photographic production processes to produce a certain affective engagement between the viewer and the image. The work of these photographers of natural history taxidermy and their diorama habitats remediates the taxidermied animal as a “questioning entity,” Baker’s description (after Derrida) of the excessive signification of animals as art (Postmodern Animal 76). Given the correspondence between the indexicality of both taxidermy and photography (Henning 138), how does this excessive signification filter through the combined surfaces of animal skin, the photographic lens, the materiality of the photographic image, and the viewer’s culturally layered perception?

I consider here some examples of how photographers of natural history museum taxidermy are remediating dead animal objects. How does photography mediate the questions these entities ask? Keeping in mind Barthes’s point about the irreducible singularity of the photographic image, I frame my analysis using Poliquin’s typology of taxidermy. Because, as she puts it, taxidermied animals “always embody an excess that resists full disclosure” (“Matter” 123), they seem not only to entice representational practices but to perpetuate representational desires. Addressing the tendency of taxidermy to signify meaning in excess of its materiality, Poliquin classifies the “talkative thingness” of taxidermied animals by the types of narratives they evoke: descriptive, biographical, cautionary, and experiential. In the descriptive mode, a taxidermy signifies on the basis of its “mimetic capacity” (128), that is, its resemblance to the living animal it once was. Because it is “supposed” to represent that animal, however, ultimately it elicits in the viewer the realization that it stands in for others of its kind. The individual animal it once was is thus erased. By contrast, taxidermies that work in a biographical mode signify particularity; their representation relies upon supplementary documentation that details the historical facts of their acquisition. Here, Poliquin emphasizes the accrual of meaning as these objects “move between and interact with various social contexts” (129), which I would argue continues in their daily encounters with curators and visitors in the museum exhibit. The now-deteriorating taxidermies of natural history museums and the ironic self-reflexivity of taxidermies in art exhibits best exemplify the cautionary mode, which Poliquin describes as the “admonition and censure” viewers experience when the taxidermy exhibit emphasizes the “loss and destruction of species and habitats” (129). Cautionary modes of signification may overlap with experiential modes. Experiential modes, according to Poliquin, arise from a “visceral” encounter between the viewer and the dead animal object. In this mode of signification, the viewer is struck by the “embodied ‘thingness’” of the dead animal, the “strange aura” surrounding “lively yet dead creatures collected together for the purpose of looking” (129). Eliciting an emotional response in the viewer that seems to be linked somehow to the interfaces of skin and surface, the experiential mode of taxidermic encounters may be the most useful category in Poliquin’s typology as it illuminates the additional layers of signification created by lens-based media. As Poliquin’s typology makes clear, even in a purely descriptive mode, taxidermy is loquacious; moreover, the fluidity of her typology makes excessive signification all the more likely. One question, then, is whether taxidermy photography can be effectively characterized by a typology developed to characterize material objects. To put it another way, what distinguishes the signification of the spectrally dead animal object remediated in the photograph from the signification of its materially dead counterpart in the diorama? Inasmuch as a photograph is also a material object, it seems the question is answerable in part through Poliquin’s typology. The very fact that so many photographers are focusing their attention on these objects suggests that they, too, may be asking similar questions In this case, practice thus precedes and is perhaps informing an aesthetic theory of taxidermic (and photographic) surfaces.

Figure 3: Nicole Hatanaka, Back Room, 2009, archival inkjet print, courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

Like many of these photographers, I begin my investigation in the museum storage room. Returning to Connor’s comment that taxidermy is “an art that conceals art” (2), one might well wonder what goes on “back there,” behind the scenes, in making this art. A conspicuous absence of human presence is evident in many of these behind-the-scenes photographs. In Back Room (2009), from Nicole Hatanaka’s series Taxinomia, for example (Fig. 3), the viewer is shown a length of pristine white storage cabinets over which presides a row of mounted rams’ heads. A grouping of headless antlers on an adjacent countertop catches the sunlight from a nearby window. The mimetic capacity that Poliquin ascribes to taxidermy in the descriptive mode is obvious in the mounted animal heads, the familiar genre of taxidermy known as the hunting trophy. This genre, common both within the natural history museum and in other contexts, works in the descriptive mode by using the bodiless head of an animal to signify the whole animal as a representative — indeed a prize — specimen of its kind. As the viewer’s gaze moves to the next most prominent set of objects, however, the headless antlers, the mimetic effect diminishes somewhat in their haphazard organization. Their disarray calls attention to the “social processes,” such as their procurement and preparation, that are “sidestepped” (Poliquin, “Matter” 128) in the descriptive mode of traditional natural history museum display. More enigmatically, in the background atop another cabinet, the viewer can detect (but just barely) an object resembling a monkey under a layer of transparent plastic wrap. The plastic covering further alludes to processes of preparation, storage, and restoration underway in this laboratory-like environment. The transparency of the dead animal object mounted in a pose typical of its kind — the descriptive mode of the taxidermy created for scientific reference in the museum — is ironically revealed here to be just that — a surface the viewer can see through. Rather than narrating their status as typical specimens of science, then, these objects narrate their status as created artifacts. Additional sheets of transparent plastic can be seen on the floor toward the back of the room, and again along the top of cabinet behind the rams’ heads. In Poliquin’s typology, this proliferation of surfaces instantiated by the photograph renders the dead animal objects more biographical than descriptive. This effect is intensified by the photographer’s framing of their laboratory-like setting. The image depicts the spaces in which museum staff members do their work; the dead animal objects in this space accompany the workaday routine.

Figure 4: Nicole Hatanaka, Storage, 2009, archival inkjet print, courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University

The “fluctuation” that Poliquin observes in the descriptive mode between “reading a taxidermy mount as a material presence of an animal and as an abstract marker within a theoretical [classification] system” (“Matter” 129) is especially evident in another of Hatanaka’s photographs from the Taxinomia series, Storage (2009) (Fig. 4). In this image, the viewer is permitted a close-up look into one of these storage cabinets, glimpsing the back end of what appear to be a mounted deer, the tails of two other unidentifiable creatures, perhaps also mounted, and a large, unidentifiable boney object. Here, the photograph, by mediating what is seen and especially how it is seen, filters the narrative the objects collectively tell. These neatly arranged objects in the storage cabinet are real animal things; they are so real, in fact, that their material presence fills the cabinet beyond the frame of its opening. With their descriptive tags, they could easily be shifted onto the exhibit floor and arranged in some sort of classificatory system for viewing. One tag, for example, describes the large bony object as “WALRUS,” though which part of the walrus this object could be is not clear. As the mysterious tags and selective framing of this photograph intimate, these varied denizens of a backroom storage cabinet resist such easy classification. Conceptually, then, the storage cabinet in this image becomes another surface the viewer encounters, a sort of diorama in which an uncertain drama is being enacted. In describing the Taxinomia series, Hatanaka links the preservation of dead animal objects with their study. She wants to find out, in photographing these back rooms and the objects within them, “what gets preserved and what gets thrown away,” “which objects are put on a pedestal and which in a drawer,” “what determines value.” In attempting to deconstruct such binaries as “order and disorder, official and non-official, valuable and insignificant,” she is trying to “reframe the ways in which meaning may be constructed and interpreted” (Taxinomia [Artist’s Statement]). As with dioramas created for public consumption, the objects in Hatanaka’s photographs of sequestered dioramas do correspond to an ordering principle of selection of what gets preserved and ultimately represented. In this sense, they signify in a descriptive mode. Yet by their very remediation through the photographer’s framing, which includes surfaces and interiors the viewer cannot fully see through or into, these objects also signify in a biographical mode. In this way, they continue to “accrue meaning,” evoking that which “enables their existence” (Poliquin, “Matter” 129).

Figure 5: Danielle Van Ark, untitled, 2006, from The Mounted Life, courtesy of the artist.

Hatanaka’s question about the value of these artifacts touches on their historical and epistemological significance. Photography of taxidermy and objects related to taxidermy in museum storage rooms compels viewers to take stock of taxidermied animals as “surplus” objects in the imperialist accumulation of knowledge of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One question these objects raise is whether natural science still needs all of these animal bodies, or whether their accumulation was more a matter of documenting territories conquered and resources gained. How and what do they still signify in the postcolonial era and relative stasis of museum storage rooms? The photographs of Danielle Van Ark’s series The Mounted Life demonstrate some ways that natural history taxidermy photography extends Barthes’s formulation of the photograph as a frozen moment in time to include a kind of motionless incipience in the image. In freezing time yet also suggesting some sort of future, they show how photography of natural history museum artifacts behind the scenes remediates animal artifacts in an experiential mode. In one photograph from the series, a taxidermied deer seems to peer out from between two cabinets (Fig. 5), in another a rhinoceros appears to gaze impassively over a work space (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Danielle Van Ark, untitled, 2006, from The Mounted Life, courtesy of the artist.

Something seems about to happen in these images despite the non-aliveness of their subjects and the conspicuous absence of human agents. The deer (Fig. 5), “caught” between two metal cabinets, appears to gaze at something out of the frame; beyond the cabinets and out of focus near the edge of the frame of the image, a window, letting in natural light, suggests a way out — of both the storage room and the photograph. In contrast to a diorama exhibit, which in recreating the animal’s natural surroundings would elide any evocation of the taxidermied animal’s “desire” to be elsewhere, this image evokes in the viewer a narrative of ungulate longing that exceeds the literal account of what the deer taxidermy is actually “doing” in storage. The donkey in another of Van Ark’s photographs (Fig. 7) evokes a similar narrative of longing to escape from what appears to be a closet, and again, a shaft of natural light emphasizes its apparent captivity within this small space. Significantly in this image, the viewer, sharing the donkey’s vantage point, is also waiting by the door. In terms of Poliquin’s typology, these two images work in an experiential mode, drawing the viewer into the image to wait alongside the donkey. In this way, the incipience is co-constituted. In Figure 6, a rhinoceros seems to impose itself on the unpopulated work space, its head jutting out into an apparent walkway while behind it loom two trash cans. What work is being impeded by this large animal? Could the utility of taxidermy itself be in peril? In describing her work, Van Ark identifies an emotional impetus: “the way these animals are haphazardly stored by humans ... results in the most moving scenes” (qtd. in Singer n.p.). The storage rooms in her photographs become, like those in Hatanaka’s images, diorama-like in the dramas they suggest. Precisely because of the haphazard juxtapositions of the denizens of these back room habitats indeed, precisely because they bear so little resemblance to the animals’ actual habitats — these interiors seem to give rise to a new afterlife for their occupants. Still, it is only through the surface of the photographic image, which renders transparent what backroom storage cabinets, closed doors, and cluttered workspaces have made opaque, that the viewer can discern it.

Figure 7: Danielle Van Ark, untitled, 2006, from The Mounted Life, courtesy of the artist.

What of animal skins in museum storage that were never intended for display, for example, the drawers full of bird skins used by taxonomists? The spectral aspect of the taxidermy photograph is most evident in images featuring such artifacts. The images in Jules Greenberg’s series Fallen, both descriptive and biographical, also evoke the spectrality of Barthes’s formulation of the “irreducible singularity” of the photographic subject. What matters here is the indexical function of the animal body itself to the others of its kind, time, and place. While the real bird skin in the drawer indexes its relationship to others for a scientific purpose, the photographic bird skin gestures beyond the realm of literal description. As with Hatanaka’s deliberate framing techniques, Greenberg’s framing of the bird bodies establishes an other-than-scientific narrative. One photograph, for example shows a cropped image of a bird against a stark black background; tags tied to one of its legs identify the specimen and describe when and where it was taken. Providing little context (for example, not showing the bird as an object in the museum’s archive of drawers), the photograph seems to function redundantly as a second index of this indexing. Yet the artist’s cropping and minimal use of color re-present the specimen as biographical. The lack of head and color and the starkness of the tags against the black background shift the narrative of this bird specimen toward a subjective understanding of this bird in this time.

Considered in their entirety, the images in Greenberg’s Fallen series do more than merely archive the surplus contained in the natural history museum storage room. While in some of these images the viewer can see the taxonomically important identification tags, by the artist’s own account, these images are “elegiac”: “In the tradition of nineteenth-century postmortem photography,” she writes, “Fallen offers a confrontation with the dead. In this sense, the series is a sort of ‘corpse meditation,’ like that practiced by Buddhist monks who sometimes sit with dead bodies or stare at images of them for days, pondering the fleetingness of life and the inevitability of death” (Greenberg, Artist’s Statement). The portrait-like photograph of two taxidermied owls with cotton stuffing for eyes exemplifies this idea. A cautionary reading of these images is also apparent in her selection of subjects. Birds, she writes, have a “long symbolic history as both ominous harbingers of death and envied icons of freedom.” The fact that so many of them have been “stored in the darkness of closed drawers” elicits in Greenberg a mourning response similar to the response elicited, as she puts it, by “the unrecounted ‘casualties of war’... whose deaths have been ignored, disavowed, or rationalized in the name of freedom, security, progress, and even peace” (Greenberg). The cultural history referenced in the artist’s statement about these photographs further mediates their impact, effecting an experiential mode of viewing through the pathos of mourning.

The surplus of dead animal bodies in museum storage rooms, which gives rise to a surplus of signification in taxonomy (see, for example, Malone), also leads to surplus of photographic mediation in the works of Sarah Cusimano Miles and Martha Frey. In Miles’s series Solomon’s House, the artist undertakes an elaborate digital photographic process involving multiple exposures of the same image using different focal points layered and stitched together in high-resolution composites that extend the depth of field. The effect, as she describes it, is to include “much more photographic information in the print than was possible to record in a single image” (Miles 5). Though placidly still-life-like in their composition, as in the photograph Lilac-breasted Roller (Coracias caudate) with Kumquats (2010) (Fig. 8), these photographs nevertheless have a disquieting effect on the viewer, who is forced to contend with a “hyper-real photographic space” (Miles 9) in which every detail is in the sharpest possible focus.

Figure 8: Lilac-breasted Roller (Coracias caudate) with Kumquats, from Sarah Cusimano Miles’s Solomon’s House series, 2010.

Neither the human eye nor a single camera lens, on its own, can apprehend reality in this way. Comprised mainly of the malleable skin of the once-living animal, these dead animal objects are also highly malleable as digital media. The malleability of images in digital media allows Miles to “play with the truth-claim of the photograph” (Miles 10). In Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) with Specimens (2010) (Fig. 9), Miles combines the layering of her photographic technique with the layering of the objects in the photograph, creating a proliferation of surfaces that the viewer might experience as crowded were it not for the formal composition the artist imposes on the objects. The image shows a deer skin carefully arranged in overlapping layers on what appears to be a bed of protective paper lining a metal shelf. Although the skin of the deer and its hooves extend past the edge of the shelf, creating a destabilizing effect, the neat row of specimen jars lining the shelf above the deer skin serves to fix it in place. The truth-claim of this photograph — that it represents a singular moment in time — is called into question when the viewer apprehends the imaging process of the multiple exposures that create multiple layers. Similar to the nature morte genre these two images reference, time seems to have stopped, even as the combined surfaces of animal skin and photographic image multiply. In this hyper-descriptive and subtly experiential mode, Miles is thus able to negotiate for herself and her viewers what she considers to be the “contradiction of empathy for the organisms and consumptive fascination with the specimens” (Miles 4), these “accumulated and warehoused” objects (Miles 1).

Figure 9: Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) with Specimens, from Sarah Cusimano Miles’s Solomon’s House series, 2010.

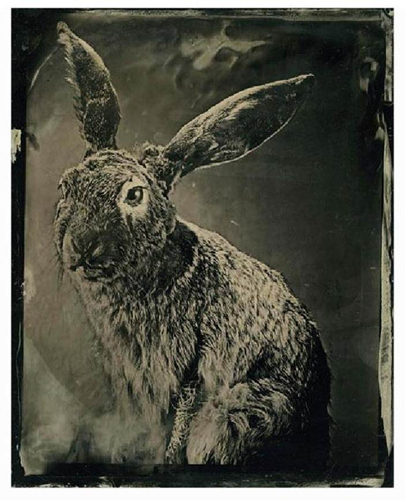

For a taxidermy to work in an experiential mode, according to Poliquin, the viewer must not have to rely upon a descriptive text to discern what is going on; the encounter must be more of a “visceral” one, “a recognition of the embodied ‘thingness’” (“Matter” 129) of the dead animal object. Certainly this is the case in the photographs of Mary Frey’s Imagining Fauna series. Like Miles’s images, Frey’s images create an affective engagement with the viewer through a deliberate photographic technique. Unlike Miles’s digital manipulation, however, Frey achieves an experiential effect using a much older, nineteenth-century photographic wet-plate process known as the ambrotype. In Imagining Fauna, the one-of-a-kind, black-and-white images resulting from this process emphasize the tattered, reliquary aspect of the natural history taxidermy she chooses to photograph. In Frey’s image Black-tailed Jack Rabbit (2010) (Fig. 10), a bedraggled rabbit, whiskers drooping, gazes resolutely beyond the frame just over the viewer’s left shoulder, the exposed armature of its left front leg betraying its taxidermic status. Uneven tones, an artifact of the wet plate process, swirl around the image of the rabbit and along the borders. It is as if the image of the animal is being filtered through a dream.

Figure 10: Black-tailed Jack Rabbit, from Mary Frey's Imagining Fauna series, 2008-2010.

Frey’s artist’s statement explains how her chosen medium complements the subject matter in this series. Comparing taxidermy with photography as both “enabl[ing] us to stare, scrutinize, and become voyeurs” (Frey), she also links the “aging biological collections housed in science museums worldwide” with this old-fashioned image-making technique. “The fragility of an ambrotype’s glass substrate,” she says, “echoes” the fragility of these old taxidermy specimens. In light of Poliquin’s point that experiential narratives are more likely to arise from “very old” taxidermy (“Matter” 129), Frey’s medium and subjects place her work decisively in this category. Yet her images in the Imagining Fauna series signify in a cautionary mode as well. Documenting the prospect of the imminent loss of vintage taxidermies perhaps soon to be discarded, they also summon in the viewer an anticipation of posterity. The talkative thingness of the taxidermied animal, represented in and remediated by the photograph, thus differs from that of the dead animal object both in kind and in degree.

The contradiction of surplus and imminent loss of dead animal objects plays a key role in the signification of taxidermy photography, as do the photographic techniques of layering and framing. In the new context of art gallery space, with its discourses of curation, creation, and cultural critique, these concepts and technics establish aesthetic taxidermy photography as a co-constitutive medium. Moving away from images of the natural history museum back rooms and storage cabinets into images of taxidermy on exhibit, I cannot help but notice, in contrast to their absence of living things, how peopled they are, and how variously the planes and surfaces of the exhibit spaces negotiate the interactions between the living and the dead. As photographer Diane Fox puts it, “nature comes to us, viewed through [the] glass windows” of zoos, natural history museums, and electronic screens (Fox). In her UnNatural History series of photographs of natural history museum exhibits, Fox deliberately references this mediation by emphasizing the glass display cases of the exhibits, in effect creating whole new dioramas for the dead animal objects on display by incorporating equally spectral images of their living human visitors reflected in the cases. For example, in Porcupine Family, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California (2011) (Fig. 11), the viewer can clearly make out the lone porcupine taxidermy clinging stiffly to a tree in its diorama, while off to the lower right, reflected in the diorama’s glass case, the silhouettes of several human figures seem to hover above their own shadows, which create another layer of silhouette. Still another layer of reflected silhouette — though of what, is not clear — is superimposed on these human figures which, in turn, are superimposed on the limbs of the tree in the diorama, bringing the eye back to the porcupine.

Figure 11: Porcupine Family, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, 2011, from Diane Fox's UnNatural History series.

Similar to the photographic layering in Miles’s museum storage room still lifes, Fox’s museum exhibit images are also comprised of a complexity of layers, though in this case it is the layers of glass, light, and shadow that create a disorienting surplus of visual information within the images. Although the viewer of this photograph seems to have the privileged vantage point of a straight-on, unobstructed view of the dead animal object within the “real” space of its glass encased habitat, the viewer is also challenged to navigate the photographic space between this real thing and the apparitions surrounding it. Then, in an experiential flash of recognition, the viewer realizes the joke: she too is caught up in the consuming gaze of the silhouettes in the background, and it is she, along with her fellow museum visitors, that comprises the porcupine family in the diorama, even as the lone porcupine in the tree seems to gaze at something else entirely beyond the frame of the photograph.

In playing with multiple vantage points and transparent surfaces, Fox’s UnNatural History images also juxtapose the artificial “natural” environment of the diorama with the real built environment of the museum space. In the photograph Wild Dogs, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, California (2010) (Fig. 12), this juxtaposition is evident in the exterior wall of windows and support columns that are visible through the glass case of the diorama. Here, the viewer, sharing the vantage point of the wild dogs, enters the photograph by becoming a witness, along with them, to the comings and goings of the museum visitors beyond the diorama. The view is through a glass case, as it is possible to see the light reflecting off the glass and below, in the right-hand corner of the image, a bit of the frame of the case itself. Despite the anchoring effect of this bit of frame, however, the boundaries of the case are not entirely clear: the sandy ground on which the wild dog taxidermies stand gives way imperceptibly to the museum floor, and the heads of the taxidermied animals themselves seem to fade into the blurred silhouettes of the museum visitors beyond them. In Fox’s photographs, the view into the natural world is thoroughly experiential, a “physical encounter between viewer and thing” (Poliquin, “Matter” 129) in which the viewer must grapple with the multiple interacting surfaces of the taxidermy on exhibit, in which everyone, both human and animal alike, within the frame and beyond, gets caught up.

Figure 12: Wild Dogs, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, California, 2010, from Diane Fox's UnNatural History series.

Co-constituting Surfaces: Natural History Taxidermy Photography Relocated

While natural history taxidermy photographers Hatanaka, Van Ark, Greenberg, Miles, and Frey emphasize the artifactual aspect of the dead animal object, its talkative thingness as a signifying surface that urges still more to be written upon it, other photographers gesture more broadly toward what has been, and could yet be, inscribed upon the dead animal object. These works point to the co-constitution of the photographic surface with broader cultural forces beyond the natural history museum. While Fox’s photographs suggest a world outside the museum in the blurred movement of the visitors walking through the exhibit past museum windows, the work of Jason DeMarte blatantly juxtaposes and layers the dead animal objects in their dioramas with other, obviously “faux,” objects not typically found in the natural history museum. Forage (2007), for example (Fig. 13), confronts the viewer with two images: one shows a taxidermy of an arctic wolf posed as if about to pounce on prey; below it another image shows a TV dinner in which the stylized colors of the food items are further offset by the garish orange of the compartmentalized plastic tray in which each item is embedded.

Figure 13: Forage, 2007, from Jason DeMarte's Utopic series.

This and other photographs from DeMarte’s Utopic and Nature Preserve series, through juxtaposing and layering such obviously fabricated objects of modern consumer culture into the visual display of natural history museum artifacts, draw the viewer’s attention to the false reality of the taxidermy and diorama. Calling into question the desirability of these highly manufactured items, DeMarte’s photographs also question the pleasure derived from viewing animal skins in simulated habitats.3 This question becomes even more pointed in photographs in which the dead animal objects that once populated the dioramas are replaced entirely by photographic images of guilty pleasure finger foods in animated poses: strips of fake bacon frolic across a windswept beach, fried chicken legs dance in a field of flowers, Cheetos® line up in front of a butte. Referring to the absent thing indirectly, these tasty faux food objects work in an indirectly descriptive mode, signifying the equally consumable animal that is represented, in the viewer’s recognition of the natural history museum exhibition genre, by the dead animal object of the (missing) taxidermy. The consuming gaze that taxidermies seem to invoke is at play here; there seems to be no escaping them, not even in their absence. Once again, the joke is on the viewer: consuming these dead animal objects is a guilty pleasure; we crave them, though they lack corporeal substance (just as the faux food objects do).

In his artist’s statement, DeMarte says that he is investigating “how our modern day interpretation of the natural world compares to the way we approach our immediate consumer environment.” Our “unnatural experience of the so-called ‘natural’ world is reflected in the way we, as modern consumers, ingest products. What becomes clear” in making and viewing these images, he explains, “is that the closer we come to mimicking the natural world, the further away we separate ourselves from it” (DeMarte). Many of the images in the Utopic series further emphasize this separation by layering in the concept of the surplus value of consumable objects, calling into question the unnaturalness of the “use, toss, repeat” pattern of American consumer culture. In Eager (2008), for example (Fig. 14), colored dot stickers such as one might use to label items in a garage sale litter the beaver dam landscape of the diorama. Such is the eagerness of beavers in building their dams that, like the acquisitive zeal of humans building the suburban housing developments that give rise to the very excess necessitating garage sales, they may go a little overboard. Art gallery visitors, recognizing themselves in this image of “eager beavers,” experience anew their distance from the natural world they occupy. DeMarte digitally layers the sticker dots onto this and other images in the Utopic series to elicit a cautionary response in the viewer as well as an experiential one.

Figure 14: Eager, 2008, from Jason DeMarte's Utopic series.

Everything about these scenes is fake, these intrusive objects remind us; in attempting to preserve nature through the indexicality of taxidermy and photography, the best we can manage is ironic references to our own tendency to overconsume. The titles of DeMarte’s two series on natural history museum taxidermy, Nature Preserve and Utopic, suggest the remediating potential of photography to relocate the dead animal objects and their faux habitats outside of natural history museum exhibit space. Layering representations of traditional dioramas with references to contemporary cultural phenomena outside the purview of museum space, DeMarte’s highly evocative photographs experientially refigure the taxidermied animal as a “provocatively visceral presence” (Poliquin, “Matter” 130) not only in art gallery space, but as a co-production with popular consumer culture.

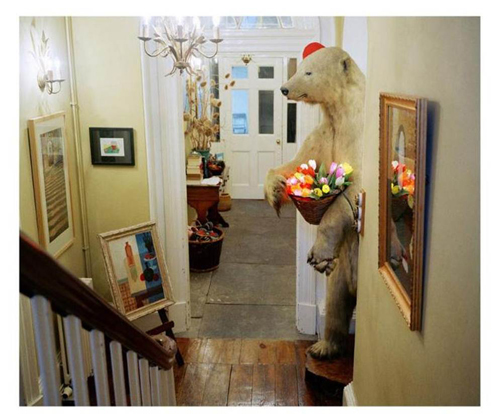

That the surfaces of natural history taxidermy are culturally layered and thus invoke further remediation and relocation characterizes the ambitious project of Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir and Mark Wilson to photograph every stuffed polar bear in the United Kingdom, and after that to move a number of them into temporary new exhibit space. The resulting work, Nanoq: flat out and bluesome: A Cultural Life of Polar Bears, operates in all four modes of Poliquin’s typology. As a descriptive project, Nanoq “presumes the mimetic capacity and value of taxidermy,” as Poliquin puts it (128), in compiling a visual and textual catalogue of what turned out to be a total of 34 mounted polar bears in situ, “as they appear in their respective museums and private homes, on display, in storage, or undergoing restoration” (Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson, 13). The mimetic potential of these dead animal objects resides not only in the photographers’ visual documentation of the mounted bears’ various cultural habitats which include both public and private spaces. Taking more than three years to carry out this documentary effort, Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson also painstakingly documented, through interviews with curators and private owners and by compiling whatever archival texts were available, the killing, mounting, and ownership lineage of each bear. This aspect of the project rendered it highly biographical, as well. Each polar bear has its own story of acquisition and display, a story that necessarily includes human actors. Regarding the bear in the Dover Museum, for example, we find that it was one of 60 polar bears shot in Franz Joseph Land in the Arctic Circle between 1894 and 1897 by Dr. Reginald Koettlitz, MD. Once mounted, the bear then spent more than 60 years in the reception/waiting room of the Dover hospital, after which it was donated to the Dover Museum, where it was cleaned and restored in the 1980s (Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson 2006, 101). In compiling these detailed biographies, Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson mapped out the “cultural life” that the Nanoq project narrates. According to the photographers, “we were aware that in undertaking the tracking down of bears, we were involved in a process that in some way mirrored the original acts of hunting. [But] it was a cultural hunt,” they clarify, one that was also about collecting (Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson 2006, 15). The Somerset bear (Fig. 15) biography exemplifies the personal aspect of collecting, as this bear is part of a larger private collection of antique artifacts.

Figure 15: Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir and Mark Wilson, Somerset, 2004. Status: Adult, vertical mount; Source: Fox's Glacier Mint factory; Acquired: 1973; Donor: Bought from the factory by the present owner's sister; Preparation: Unknown; Current Location: stands in the hallway of a private residence, Somerset; Notes: Given to the present owner by his sister on his 21st birthday.

For Snæbjörnsdóttir, collecting the polar bear photographs became a way of connecting to her own family history, since “Snæbjörnsdóttir” translates from Icelandic into English as “snow bear’s daughter.” In describing this connection, the artist asks, “What better way to find one’s bearings in relation to an unfamiliar environment to which one is nevertheless instinctively drawn, than to connect by means of a name to one of the most powerful icons on earth” (14)? While Snæbjörnsdóttir’s personal connection to the polar bear constitutes, for her, an experiential mode of representation, her reference to the iconic status of the polar bear layers a more general cautionary element onto the narrative. An endangered species whose decline is virtually synonymous with anthropogenic climate change, the polar bear derives power even from its decline, as humans intervene to protect it and, by association, the entire planet. More than just a personal mission, then, Nanoq also became a mission to relocate several of the polar bear taxidermies to an art exhibit space (Fig. 16), where they could, as the artists put it, “generate a discourse in which audiences [would be] able to consider their relationship not only to the ‘polar bears’ themselves, but to the history of their collection, presentation and preservation” (14).

Figure 16: Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir and Mark Wilson, Exhibition at Spike Island, Bristol, 2004.

Baker touches on the relational aspect of the Nanoq exhibit in explaining the significance of the relocation of the polar bears into art space: “Works of art are active things, actively to be engaged with” (Baker, “What” 149). In this way, they become experiential to the wider viewing public; more than merely a collection of things, they become an opportunity for people to have “new experiences of the bears, new interpretations of their histories, new emotional responses to them, and new understandings of the spaces that the bears might come to occupy” (Baker, “What” 154). Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson’s Nanoq: flat out and bluesome: A Cultural Life of Polar Bears has become a touchstone project in the relocation of natural history taxidermy to art space (Aloi 37-39; Broglio, Surface Encounters 72-80; Patchett “Animal as Object”).

Conclusion: Surface Tension

Applying Poliquin’s typology of taxidermy to its photographic remediation makes manifest a surface tension between viewer and image, between the consuming gaze and the object of desire. Filtering the taxidermic surfaces of dead animal objects through lens-based media seems to emphasize the complementary forces inherent in the four modes in which taxidermy signifies. The mimesis that is characteristic of the descriptive mode, for example, can be seen to invoke an erasure, as well, when the indexicality of the talkative thing to its referent is cropped, as in Hatanaka’s and Van Ark’s images of taxidermies in storage cabinets; hazy, as in Frey’s ambrotypes; or hyperreal, as in Miles’s multiple exposures. What is more, the erasure inherent in the descriptive mode seems also to invoke a sort of testimonial aspect characteristic of the cautionary mode, as in Greenberg’s images of Fallen bird taxidermies that gesture toward other “ignored” and “disavowed” dead, and DeMarte’s consumerized dioramas dramatizing the unrequited desire of our separation from nature.

As with the literal phenomenon of intermolecular forces creating a barrier between liquid and air and thus giving shape to liquid, as when rainwater forms beads on the surface of a newly waxed car, the surface tension developing from the photographic remediation of natural history museum taxidermy seems the inevitable result of the imbalance of energy in the tendency of taxidermic things to signify in excess of their skins, as Poliquin so effectively describes (Breathless). By talking their way out of their natural history museum via the lens-based media of these photographers, these dead animal objects seem restlessly to revise the larger narratives from which they have arisen, taking new shapes and creating new meanings in cultural practices of animal representation.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Susan Ressler and Michael J. Faris for their contributions to this article.

Notes

1. The term “dead animal art” is most often associated with the work of the artists’ collective known as the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists (MART); it is the name of the website of MART founding member Scott Bibus.

2. That a digital image is as much a material object as an image produced analogically has been theorized at length. The camera’s capacity to record images is what gives those images material reality, according to Mark J. P. Wolf (419). Paul M. Leonardi argues for a definition of “materiality” in which matter is understood as anything with the potential for the “practical instantiation of theoretical ideas” (n.p.) See also Bolter and Grusin, 105-112; and Sassoon, 186-202.

3. In theorizing the difference between analog and digital photography, Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin argue that photographs can be distinguished “on the basis of their claim to immediacy,” something the viewer desires as much, if not more, than their veracity. The irony with which Fox’s and DeMarte’s photographs are intended to be viewed, by calling attention to the photographs themselves, remediate immediacy by privileging the representation of its desire (110).

Works Cited

Asma, Stephen T. Stuffed Animals & Pickled Heads: the Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums. London: Oxford UP, 2001.

Baker, Steve. The Postmodern Animal. London: Reaktion Books, 2000.

Baker, Steve. “What Can Dead Bodies Do?” Nanoq: Flat out and Bluesome: A Cultural Life of Polar Bears. Ed. Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir and Mark Wilson. London: Black Dog, 2006. 148-155.

Baker, Steve. “‘You Kill Them to Look at Them’: Animal Death in Contemporary Art.” Killing Animals. Ed. The Animal Studies Group. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 2006. 69-98.

Barthes, Roland. 1980. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1999.

Broglio, Ron. “A Left-Handed Primer for Approaching Animal Art.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 9. 1 (2010): 35-45.

Broglio, Ron. Surface Encounters: Thinking with Animals and Art. Minnesota: U of Minnesota P, 2011.

Connor, Steven. “Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On.” Steven Connor, 2009. Web. 28 January 2012.

DeMarte, Jason. “Artist’s Statement.” Jason DeMarte, 2009. Web. 25 January 2012.

Desmond, Jane. “Postmortem Exhibitions: Taxidermied Animals and Plastinated Corpses in the Theaters of the Dead.” Configurations 16 (2008): 347-77.

Dillon, Brian. “Rereading: Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes.” The Guardian 25 March 2011.Web. 18 November 2011.

Fox, Diane. UnNatural Histories.“Artist’s Statement.” Diane Fox Photography, n.d. Web. 18 November 2011.

Frey, Mary. Imagining Fauna. “Artist’s Statement.” Mary Frey Photography, 2008. Web. 18 November 2011.

Greenberg, Jules. Fallen. “Artist’s Statement.” Jules Greenberg Photography, 2005. Web. 11 November 2011.

Hansen, Rikke. “Animal Skins in Contemporary Art.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 9. 1 (2010): 9-16.

Haraway, Donna. “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1936.” Social Text 11 (1984): 20-64.

Hatanaka, Nicole. Taxinomia [Artist’s Statement]. Nicole Hatanaka, 2010. Web. 11 November 2011.

Henning, Michelle. “Skins of the Real: Taxidermy and Photography.” Nanoq: Flat out and Bluesome: A Cultural Life of Polar Bears. Ed. Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir and Mark Wilson. London: Black Dog, 2006. 136-147.

Houlihan, Kasia. (2004). “Annotation of Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida—Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981).”The Chicago School of Media Theory, 2004. Web. 10 November 2011.

Leonardi, Paul M. “Digital Materiality? How Artifacts without Matter, Matter.” First Monday 15.6 (2010). Web. 30 Nov. 2012.

Malone, Margaret E. “Increasing the Use and Value of Collections: Finding DNA.” MA Thesis. Baylor University, 2010. Web. 18 November 2011.

Milgrom, Melissa. Still Life: Adventures in Taxidermy. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

Miles, Sarah Cusimano. Solomon’s House. MFA Thesis Statement. University of Alabama, 2010.

Patchett, Merle M. “Animal as Object:Taxidermy and the Charting of Afterlives.” Unpublished web article, 2006.

Patchett, Merle M. “Putting Animals on Display: Geographies of Taxidermy Practice.” Diss., University of Glasgow, 2010. Web. 11 November 2011.

Poliquin, Rachel. The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State UP, 2012.

Poliquin, Rachel. “The Matter and Meaning of Museum Taxidermy.” Museum and Society 6.2 (2008): 123-134.

Quinn, Stephen Christopher. Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History. New York: Abrams, 2006.

Sassoon, Joanna. “Photographic Materiality in the Age of Digital Reproduction.” In Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images, ed. Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart (London: Routledge, 2004): 186-202.

Singer, Jill. “The Making of The Mounted Life by Danielle Van Ark.” Sight Unseen, November 2009. Web. 11 November 2011.

Snæbjörnsdóttir, Bryndís and Mark Wilson, eds. Nanoq: Flat out and Bluesome: A Cultural Life of Polar Bears. London: Black Dog, 2006.

Wolf, Mark J. P. “Subjunctive Documentary: Computer Imaging and Simulation.” In Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World: A Critical Sourcebook, ed. Carolyn Handa.Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004. 417-433.