The Cost of Human Exceptionalism

Humanimalia 7.1 (Fall 2015)

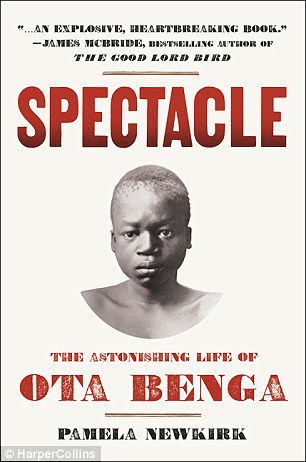

In September 1906, a pygmy named Ota Benga was exhibited in a cage in the monkey house by the New York Zoological Park. Bones were scattered around his enclosure, suggesting that he had been a cannibal, and a sign told of his provenance. An orangutan was later also placed in the cage, ostensibly to keep him company. Benga brought in huge crowds, but the exhibit immediately provoked protests, especially from the African-American community. After a while, Benga, who had up till then shown a pleasant disposition, became uncooperative and almost violent, so he was allowed to move freely on the grounds, but thousands of raucous tourists followed him about. After only about three weeks, the exhibit was discontinued.

Ota Benga then lived in a series of foster homes. For a while, he managed to thrive in a rural community around Lynchburg, VA, where Blacks retained some African traditions. He taught young men techniques of hunting, cooking, and gathering that he had learned in childhood, but he gradually became increasingly homesick. As World War I began, his hopes of ever returning to his native land faded, and his friends dispersed. In 1916, Benga committed suicide by shooting himself in the chest.

Ota Benga is remembered today as a symbol of the close association at that time between science and racism, as well as because he remains surrounded by a good deal of mystery. There is certainly no shortage of records about him, but they are full of gaps and unreliable. Pamela Newkirk’s Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga is not the first biography of him, but it is the most comprehensive to date. She has consulted a vast number of archival records, as well as newspaper and magazine articles, yet many key details, especially concerning how he was brought to the United States from the Congo and the exact nature of his captivity, remain uncertain.

Such problems in reconstructing events are common in periods of genocide, such as, for example the Armenian Holocaust in 1915 or the Holodomor (the artificially created famine in Ukraine) in 1932. King Leopold II of Belgium, who ruled the Congo at the time Benga was brought to America, was a despot on the scale of Stalin, Hitler, and Pol Pot. In 1884, the European states had held a convention in Berlin, in which they divided Africa among themselves, without the participation of a single indigenous representative from that continent. No country wished to govern the Congo, since they judged that it would be unprofitable, but Leopold persuaded the assembly to give it to him, not precisely as a colony but as a personal protectorate. He then made the Congo profitable, by enslaving the entire country, at a cost of, according to most scholars, ten million human lives. Though the historical episode is now largely forgotten, the name “Congo” can still evoke a slight shudder of terror to this day.

As Newkirk recounts in detail, Benga was first obtained by the explorer Samuel Phillips Verner, along with a few other pygmies, for display at the Saint Louis World’s Fair in 1904. In his earliest account, Verner simply said that he had found Benga in a remote part of the forest. In later accounts he claimed to have rescued Benga from a tribe of cannibals, which, as Newkirk points out, seems to be an incident borrowed from Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, in which the hero rescues the Black man who will become his devoted servant. Subsequent accounts in Verner’s writings and in the press generally mention cannibalism, but differ in their details. In some, he claims to have bought Benga from his persecutors for a bolt of cloth and a pound of salt, but in his final version it was not him but the Belgian army that saved the pygmy. After Benga’s death, The Lynchburg News reported that he had once told an unnamed individual that a white stranger, presumably Verner, had kidnapped him at the age of 13, but there is no way to verify that account. Benga returned home briefly after the World’s Fair, but once again left with Verner, this time for New York.

In summary, it is uncertain whether Verner purchased Benga as a slave, captured Benga, or simply offered the pygmy the opportunity to emigrate. The truth may be more complicated than any of those scenarios, and perhaps incorporates elements of each. Whatever happened, as Newkirk points out, Benga had surely already been traumatized even before his departure. Verner, as she amply documents, was, in addition to being mentally unstable, a racist and, even more significantly, an apologist for King Leopold.

Newkirk ends her book with a passage of wonderful eloquence, modesty, and simplicity: “While a single volume cannot being to right the grave injustice that so tragically marked Benga’s life, it can help untangle the web of egregious fallacies that mark our historical record and dishonor his memory” (260). Without a doubt, she has succeeded in that goal. Further progress will probably be made not by uncovering some long-lost document, since all records appear to be tainted, but by reconstructing the ambiance, and the way of thinking, that prevailed at the time.

It is hard even to discuss the events without risking violations of good taste, but that, of itself, is a sign of unresolved tribulations. To head off accusations of such a transgression, I will say that the suffering of Verner is obviously not comparable to that of Benga. Nevertheless, it seems to me likely that Verner as well had been traumatized by what he witnessed in the Congo, which might explain his constantly changing accounts. Perhaps his claim to being a savior and friend to Benga was not simply propaganda but also a psychological necessity, a way of dealing with extremely stressful events. Although Newkirk dismisses the possibility, I think the claim to friendship may have had, at least sometimes, an element of truth. After all, contradictions do not show whether one is lying or responding honestly, only that, whatever the intent, one is not doing a very good job of either. Despite their vast differences, Benga and Verner had shared experiences that they could not communicate with anybody else. Each was, nevertheless, a reminder to the other of events that both would have preferred to forget. I may be indulging in novelistic speculations here, but it is hard to understand the events in any other way.

Our difficulty in understanding the incident is not due solely to either apologetics for King Leopold or to repression of our racist past. The zoo in the early twentieth century was, in many ways, very much unlike the sanitized institution that we know today. People would often put on formal attire to visit, but, otherwise, it was a pretty rowdy place, and there was a good deal of interaction between animals and human beings. Despite the claim of being educational, the zoos were often not very different from the side shows, “freak shows” if you will, in the circus. The zoo made very little or no pretense of placing the animals in a natural environment. There was, from our contemporary point of view, amazingly little care taken for safety of either of the animals or the people. One brilliant but eccentric herpetologist in Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo allowed poisonous snakes to move freely about her office and possibly beyond, convinced that they had been tamed. The feeding of live rodents to anacondas was a popular, though controversial, event, which brought gasps of horror and fascination. People talked to and often fed the animals, even offering them alcoholic drinks.

It was not unusual for indigenous people such as the Inuit or Sami to be exhibited alongside beasts, although placing a human being, Benga, in the monkey house had been unprecedented. The boundary between human beings and animals was a constant source of boisterous, if uneasy, humor. It was not always easy to tell whether people were laughing at the animals, at themselves, or at society. It was not always easy to separate showmanship from science or entertainment from education. Perhaps the public enjoyed the presentation of Benga as a sort of proverbial “wild man,” including the titillating suggestion of cannibalism, while knowing full well that it was just a show. It could also be that Benga, despite his traumatized condition, could have at times played along, acting out the role he had been assigned. He was at times characterized in the press as a “zookeeper,” and his purpose was to mediate between the animals and human beings.

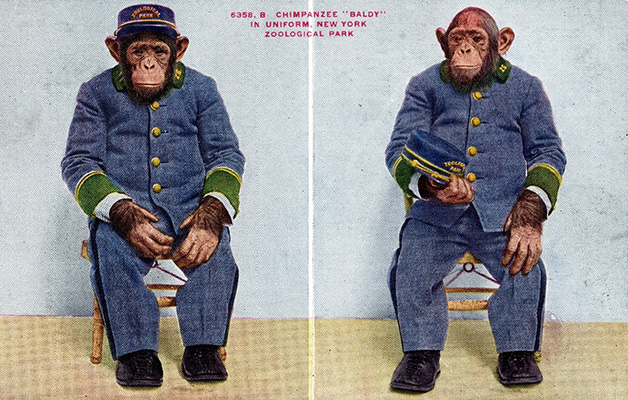

Mostly to get a better idea of the prevailing ambience, I have done a bit of research myself into the early New York Zoological Park, especially in the archives of the New York Times and other newspapers around the start of the twentieth century. After Benga departed from New York, the gap he left was, within a few months, filled by a popular chimpanzee named Baldy, who was constantly mentioned in the newspapers, and, though he did not cause as much controversy, may well have been as big an attraction as the pygmy who preceded him.

Indigenous people on public display were, at the time, shown in settings that emphasized their reputedly “primitive” character. The apes, by contrast, were presented in ways that made them appear as “human” and “civilized” as possible. At many zoos around the turn of the century, apes were taught to smoke pipes or cigars, drink wine, play musical instruments, and ride in carts drawn by dogs. At the New York Zoological Park, they would, among other acts, be displayed sitting at a table and drinking tea from fine china. An article in The Portsmouth Daily Times dated October 3, 1910, tells how Baldy, who had a reputation for unusual intelligence, was the first ape to learn to learn to eat with a knife and fork. He was then assigned to teach this skill to the orangutans, who sat with him in chairs around a table. Soon, a quarrel broke out over food, and Baldy hit one of the orangs with a chair.

Another incident, reported in the Goshen Mid-Week News on October 31, 1911, seems very clearly reminiscent of Benga. The authorities decided that Baldy would be promoted to the rank of zookeeper, and he was given a custom-made uniform, including shoes to wear on the job. Then it was time to show him about the entire zoo. Everything went well, and a crowd of over a thousand visitors soon gathered to watch, until Baldy entered the reptile house, and was spooked by the anaconda. He tore off his shoes, ran off, and started climbing around the grounds, tearing his uniform to shreds, until the keepers finally managed to lead him back to the monkey house. Needless to say, the crowd loved the spectacle. Baldy continued to represent the zoo, often dressed in human clothes, and greeted visiting dignitaries, including President Taft, by shaking hands.

None of this in any way constitutes a vindication of the New York Zoological Park. It is possible that the gesture of making Baldy a zookeeper was even a way of mocking Benga in absentia. Furthermore, there is the question of exploitation of Baldy, whose biography has yet to be written, and the other apes. The New York Zoological Park, as an ostensibly educational institution, was trying to popularize Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, which was usually interpreted as a story of biological “progress,” to the masses. To dramatize the continuity between animals and people, they needed a figure to play the proverbial “missing link,” a role that was first taken by Benga and later by Baldy. The institution did not necessarily expect everyone to take their displays completely seriously, and, despite their pedagogic aspiration, they were presented in something like the spirit of vaudeville. Baldy, in sum, was what the zoo authorities had initially intended Benga to be.

The proverbial “missing link” is a sort of archetypal figure in modern culture, still played, with variations, by various celebrities, from pro-wrestlers to writers. The sharp division that we have made between the realms of nature and civilization creates a need for intermediaries. But the figure is ultimately a fantasy, as is the human exceptionalism on which it is based. Any attempt to actually live, or to assign, that role will probably lead to tragedy, as the life of Ota Benga shows.

Figure 1: Ota Benga with a chimpanzee, from the Logansport Pharos Tribune, Sept. 29, 1906.

Figure 2: Two pictures of Baldy in his zookeeper's uniform, from a postcard published by the New York Zoological Park.