Reanimating Chicago

Humanimalia 8.1 (Fall 2016)

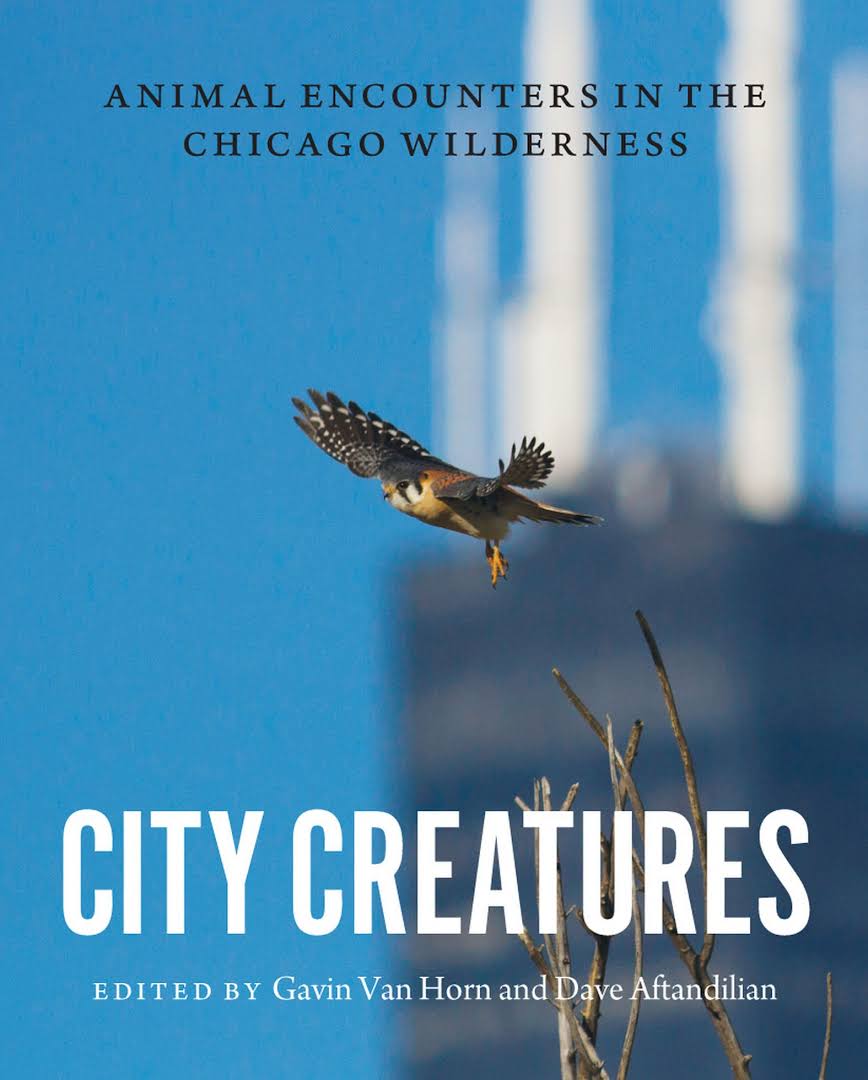

“Hog Butcher for the World, / Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat / Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler; / Stormy, husky, brawling, City of the Big Shoulders.” The first five lines of Carl Sandberg’s 1914 poem “Chicago” capture its enduring image as a bold and brash city of industry. With its pavement and steel landscape, its air thick with the aroma of hog butchering, and its corrupt culture of political cronyism, images of Chicago as a concrete jungle still persist. Dave Aftandilian and Gavin Van Horn’s edited collection, City Creatures: Animal Encounters in the Chicago Wilderness, unsettles such perceptions of Chicago by attending to “the many, surprisingly varied wild and domestic animals with whom we share our apartments and alleys, backyards and gardens, forest preserves and parks” (1). From Chicago’s meatpacking heyday and beyond, Aftandilian and Van Horn reveal that the city was and continues to be a living city filled with an astonishing variety of creatures. Even if we are oblivious to their presence, these animals see us, and, as City Creatures suggests, it is time for us to begin seeing them. To that end, City Creatures aims to “reanimate Chicago” by introducing readers to the “unexpected diversity of finned, feathered, scaled, and furry animals who live alongside us in the city and suburbs” (3). In (re)acquainting its audience with their animal neighbors, City Creatures strives to “inspire readers to care about and for them” (3). This book thus has an educational and ethical thrust geared toward changing city dwellers’ attitudes and behavior toward the nonhuman creatures in their midst.

City Creatures accomplishes this goal by adopting a story-based approach that combines a variety of genres and media, including nonfiction essays, illustrations, maps, photographs, and poems. Citing literary scholar Jonathan Gottschall’s argument that humans are “as a species, addicted to story” and conservationist Will Rogers’s claim that stories “can get through to our hearts with a message,” City Creatures uses stories as a means to inspire its audience to empathize with the animals around them (3). Rooted in the conviction that narratives foster a sense of shared community among people of different backgrounds, this volume features stories that “foreground other animals as agents … as subjects rather than objects, acting with consciousness and intention in the world.” By making Chicago’s dismissed, ignored, or unknown animals visible as actors and subjects in their own right, City Creatures hopes to change how people perceive and relate to nonhuman life in their everyday lives.

While this emphasis on nonhuman creatures as subjects and actors aligns with much of the scholarship in animal studies, and both Aftandilian and Van Horn have Ph.Ds. (in anthropology and religion respectively), this book primarily addresses itself to a non-academic audience of “part-time naturalists, urban explorers, creative artisans, outdoor enthusiasts, [and] green-space lovers” (4). In addition to these readers, the volume has a number of stories about children and childhood, focusing on the ways in which we can teach children about the world through nature or can foster a childlike sense of wonder in ourselves. For that reason, this book would also appeal to parents and teachers. City Creatures also features a diverse set of contributors, bringing together native Chicagoans, immigrants to the city, academics from the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences, as well as artists, poets, museum curators, farmers, religious leaders, and more. Filled with beautiful and provocative essays, images, and poems, City Creatures would be an ideal coffee-table gift for a nature-loving relative, a Chicago history enthusiast, a visual art aficionado, a new parent, and beyond. Priced at a reasonable $30 for hardcover and $18 for an e-book, with short and engaging sections that span no more than ten pages, the book is also ideal for high school or college-level teaching. One could imagine borrowing excerpts for a wide range of classes covering anything from animal ethics, art history, and Chicago history, to environmental studies, urban history, and literary studies. The book’s educational benefits are enhanced by the recommended resources list at the end of each essay — a useful source for further exploration and research. For students of nonhuman life, the volume also has a larger appendix at the end that is categorized by subject, with sections such as “animals in art,” “Chicago metropolitan nature,” and “philosophical and humanities perspectives on animals.”

“Why look at city animals?” To answer this question, the book begins with the following statistic: in the United States more than 80 percent of humans live in urban areas; globally, it’s around 50 percent (5). Rather than lamenting the rise of cities as harbingers of humanity’s increasing isolation from nature, Aftandilian and Van Horn suggest that we “retrai[n] our vision of cities as places of inhabitation and encounters with nature” (5). While one can commune with nature in America’s vast public lands and national parks, city dwellers can also appreciate and experience the wilderness in their own backyards. To that end, City Creatures advocates for the paradigm of reconciliation ecology, a concept coined by evolutionary ecologist Michael Rosenzweig that refers to the “science of inventing, establishing, and maintaining new habitats to conserve species diversity in places where people live, work, or play” (6). While ecological restorationists seek to mitigate and reverse the human impact on the surrounding environment, reconciliation ecologists work to create new ways of responding to other species’s needs, allowing for dynamic sites of cohabitation (6). The ecological restorationist paradigm reflects two important ideas emphasized throughout the book: 1) cities have always been embedded within nature, and 2) humans are not the only city dwellers. While humans may have created cities, many forms of nonhuman life inhabit and change urban environments — from squirrels to insects to birds of prey. With these ideas in mind, City Creatures “hopes to place the dialogue about urban conservation front and center and contribute to an ethic of care for the everyday places where people live and work” (7).

“Why Chicago?” one might also ask, harking back to Carl Sandberg’s poetic depiction of Chicago. As City Creatures reveals, Chicago is much more than the skyscrapers of its downtown. Chicago is a city of neighborhoods, parks, and waterways, and as City Creatures reveals, even Chicago’s most populated downtown areas are home to many forms of nonhuman life. In addition to Chicago proper, City Creatures covers Chicago’s metropolitan region, encompassing its vast networks of suburban forest preserves, rivers, and prairies. Chicago’s geography, topology, and hydrology have made it a popular meeting place for many animal and vegetal species (7). Thanks to the efforts of early naturalist groups, Chicago is home to institutions such as the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum (operated by the Chicago Academy of Sciences), the Field Museum, and the Lincoln Park and Brookfield zoos. These institutions make Chicago a prime destination for humans looking to encounter both familiar and unknown creatures. Aftandilian and Van Horn also remind us that Chicago is one of the birthplaces of the ecology and is home to numerous scientific organizations devoted to ecological management, such as the RESTORE project (Rethinking Ecological and Social Theories of Restoration Ecology), and the Chicago Wilderness Land Management Research Program. Chicago embodies the idea that cities are not biological deserts, but are vibrant settings to meet and study all types of nonhuman life (8).

City Creatures is comprised of six sections, each of which constitutes a potential site of human-animal encounters. Although the book is nearly 400-pages long, its format of short, readable sections makes it easy to pick the book up and return to it at one’s convenience. It would be difficult to do justice to all the rich voices in the space of a book review, but I will highlight a few from each part. The first section, entitled “Backyard Diversity,” is filled with stories, images, and poems about the animals we might encounter close to where we live, such as opossums, raccoons, and squirrels. One standout is Lea F. Schweitz’s “Mysterium Opossum,” which recounts her unexpected encounter with the sacred, prompted by young son’s query, “What is that?” upon viewing an opossum in their backyard. In attempting to answer her son’s deceptively simple question, Schweitz reflects on how “being present with urban nature and the sacred that hides within it is rarely easy; it’s ambiguous and unpredictable and fascinating, and sometimes frightening” (48). Invoking twentieth-century theologian Rudolph Otto’s notion of the mysterium tremendum et fascinans, which describes the experience of the sacred as one that overwhelms us when we confront a mystery, making us tremble in fear (the mysterium tremendum). At the same time, we are also drawn to this mystery and filled with awe (the mysterium fascinans). Schweitz and her son’s experience with the “mysterium opossum” reveals the limits she had unconsciously placed on the sacred in urban nature, forcing her to interrogate and inhabit the ambiguity she feels about a typically despised creature like an opossum. In so doing, the opossum teaches Schweitz and her son that “by abiding in the ambiguity, they can remain open to the grace in [the opossum] and the possibility of other unexpected spiritual lessons in urban nature” (49).

Section Two, “Neighborhood Associations,” travels to Chicago’s liminal spaces that are neither wild nor domestic. This section includes many highlights, such as the Puerto Rican-born and Chicago-raised poet David Hernandez’s “Pigeon,” which draws incisive and uncomfortable parallels between Chicago’s pigeons and its Latino and Hispanic residents (91). Another fascinating piece from this section is Eli Suzukovich III’s “Kiskinwahamâtowin (Learning Together),” which is about a garden restoration project at the American Indian Center in Chicago’s Ravenswood neighborhood, a part of the city better known for being home to Chicago’s mayor than for its connection to Chicago’s Native American communities. Through compelling details and stories, this essay describes how the restoration of the garden also revitalized relationships among Native languages, cultures, and communities in Chicago (106).

While “Neighborhood Associations” includes a few excellent pieces about the cats and dogs of Chicago (see Michael S. Hogue’s essay about the community-building effects of an impromptu city dog park, Susan Hahn’s poem “Wanting was an Alley Cat,” and Alma Domínguez’ paintings), I would have liked to have seen more space devoted to confronting Chicago’s massive population of homeless dogs and cats. With 20,000 dogs and cats entering Chicago’s city shelter annually, it would be worth exploring how socioeconomic inequities among Chicago’s human beings have affected its feline and canine populations. Because companion animal homelessness is a problem in cities across the United States, it would be valuable to explore what steps local animal rescue organizations and the city of Chicago are taking to combat this challenge.

Turning to “Animals on Display,” section three visits places where humans go to watch animals, including aquaria, museums, and zoos. Many of the essays, such as Joan Gibb Engel’s “Train to the Zoo” and Andrea Friederici Ross’ “Bridging the Divide: Pondering Humanity at the Zoo” confront the ethics of taking children to zoos or of supporting institutions that keep animals in captivity. Attuned to the benefits of experiencing “wild” animals up close, but also conscious of the costs exacted on the animals themselves, these essays present a nuanced picture of the ethical complexities of urban zoo-keeping. Living animals are not the only kinds of creatures on display in Chicago, as Rebecca Beachy’s “A Living Taxidermy” reminds us. Describing her experiences performing public taxidermy demonstrations at the Beecher Lab of the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum, Beachy argues that “to display the dead, in every stage of decay and preservation, enhances the possibility of actually seeing — of witnessing death and life in palpable conversation. Public taxidermy demonstration does just this” (157). Supplemented by Marianna Milhorat’s video stills depicting different stages of taxidermy, the experience of reading Beachy’s essay is akin to witnessing a live taxidermy demonstration, complete with the attendant fascination and discomfort. Terry Evans’s photographs of drawers of taxidermied birds, beautiful and heartbreaking in their stillness, are a perfect accompaniment to Beachy’s piece (175-7).

Section four, entitled, “Connecting Threads,” explores the protected areas around Chicagoland that provide habitat for local and migrating animals. Andrew S. Yang’s essay “Letting the City Bug You: The Artistic and Ecological Virtues of Urban Insect Collecting” engages with Baudelaire’s notion of the flâneur as a model for artistic engagement by questioning if there are non-anthropocentric ways of being a flâneur. For Yang, this is possible through the eyes of insects, whose diversity and ubiquity make a strong case for exploring the city from an insect’s perspective. Drawing from his experiences teaching an entomology class at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and aided by photographs captured during such entomological explorations, Yang describes the spontaneous social spaces that emerged as strangers joined his class to help collect insects at nearby parks. In addition to bringing diverse groups of people together, Yang recounts how his students developed a greater appreciation for the small creatures in our midst as they learned to experience Chicago through insect eyes.

Turning from creatures on the ground and in the air to those under the water, section five, “Water Worlds,” examines the ecologically essential, but perhaps less familiar, creatures who inhabit the bodies of water surrounding the city. The first essay, “Washed Up on the Shores of Lake Michigan” by Curt Meine, recounts what happens when the usually hidden contents of the lake rise to the surface, as they did during the great alewife die-off of 1967. During that summer, the shores of Lake Michigan were overtaken by dead alewives, a species of fish not native to the Great Lakes, thus revealing the effects of human-perpetuated environmental change. Meine uses this historical event to raise these essential questions: “Do we accept, combat, or accommodate the invasive species that come to our waters? Do we continue to see only the surface of Lake Michigan and to regard the water out there as something inert and apart? Do we persist in seeing the lake as only a commodity, lacking a relevant history, ours to reconstruct according to political and economic demands? Or do we care for the lake as a living community to which we belong?” (250). Clearly, Meine would answer in the affirmative to the final question, arguing for a broader ethic of care towards the creatures populating the Chicagoland region, including not only those living on land, but also those in the water. Following Meine’s essay is a poem by Todd Davis called “Alewives” that laments “how quickly they perish / far from home,” (253) and a photograph by Colleen Plumb of dead alewives stacked together in varying stages of decay. Together, these three pieces make a convincing case for understanding Lake Michigan not simply as a commodity to be used by human beings, but as a living, ecologically significant habitat for a diverse number of creatures.

While many visitors to Chicago are familiar with Lake Michigan, Michael A. Bryson’s “Canoeing through History: Wild Encounters on Bubbly Creek” draws our attention to the largely forgotten South Fork of the South Branch of the Chicago River located on Chicago’s Southwest Side. Nicknamed “Bubbly Creek” in the nineteenth century, this body of water earned its moniker due to the methane gas that bubbles up from the anaerobic bacterial decomposition of organic waste that makes up the creek’s sediments (264). This “organic waste” is a result of decades of using Bubbly Creek as a dumping ground for the Chicago Union Stock Yards, a decision that was justified by the false belief that the slow-moving current would wash the waste downstream (264). Despite the water’s “perpetual sickness” from human mismanagement, Bryson argues that Bubbly Creek and places like it are “potential sites for contact with wildlife and renewal of spirit — especially for urban citizens who may be plagued by a fundamental disconnection from the nonhuman world around them” (265). As a means of illustrating this point, Bryson recounts the experience of taking a class on canoes down the creek, where students spotted a majestic sandhill crane. For Bryson, this moment of sublimity in the midst of decay reflects the possibility of encountering nature in unexpected places and the hope for the creek’s eventual restoration (270-1).

The final section, “Coming Home to the City,” turns to the wild animals living in Chicago. This section includes essays, poems, and images of coyotes, buffalo, skunks, and more. One highlight is Dave Aftandilian’s piece, “Hardy, Colorful, and Sometimes Annoyingly Loud,” which describes the infamous parakeets of Hyde Park, the neighborhood home to the University of Chicago. As its title suggests, the presence of this non-native species is a contentious topic; they were beloved by Chicago’s former mayor Harold Washington and despised by those irritated by their incessant squawking. Enriched by Diana Sudkya’s beautiful and educational paintings of the parakeet nests, this essay fosters an appreciation for the birds, who promote ecotourism to Hyde Park as well as provide joy during Chicago’s bleak winters (304). Ultimately, Aftandilian suggests that the monk parakeets are best understood as a “new kind of totem animal” (305). Drawing from Graham Harvey’s definition of the term in his book Animism, totemism here refers “not just [to] the animals or plants in question, but also to the humans who feel closely connected with them, together as ‘groups of persons that cross species boundaries to embrace more inclusive communities and seek the flourishing of all’” (305). Through these birds, Aftandilian believes that we can learn about what it means to become “native” to a place and to share it with others (305).

City Creatures thus reminds us that cities are not solely the domain of human beings, and that as urban citizens we have a responsibility to attend to and care for the nonhuman creatures around us. By combining a variety of perspectives from within and outside of academia, this book is an accessible and entertaining way of seeing Chicago or any urban environment with fresh eyes. For the scholar of animal studies or nonhuman life, the book would be a useful teaching tool or entry point into a new area of interest.

Works Cited

Sandburg, Carl. “Chicago.” Poetry (March 1914).