Telling Tales in Troubled Times

Humanimalia 9.1 (Fall 2017)

The Trouble

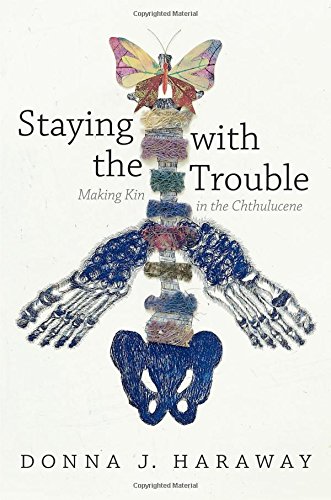

A particularly keen generosity of practice runs throughout Donna Haraway’s latest book, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Haraway shares in the same “curious” methodological practice that she attributes to philosopher and psychologist Vinciane Despret, one that “is not interested in thinking by discovering the stupidities of others, or by reducing the field of attention to prove a point” (126). Rather, such practice constitutes a kind of thinking that “enlarges, even invents, the competencies of all the players, including [one]self, such that the domain of ways of being and knowing dilates, expands, adds both ontological and epistemological possibilities, proposes and enacts what was not there before” (126-127). Only with such a change in kind, suggests Haraway, do we become capable of changing the story — aptly described here as “the prick tale of Humans in History” — that has captivated, and kept us captive, for so long. Such curious and generous practice, she continues, loosens the grips of cynical defeatism, allowing us to think outside of the “abstract futurism” that currently dominates thought and steeps us all in “its affects of sublime despair and its politics of sublime indifference” (4).

For Haraway, the prick tale’s current iteration can be approached most clearly through the work performed by the conceptual frameworks known as “the Anthropocene” and “the Capitalocene.” Haraway convincingly argues that such terms, which are more or less commonplace in academic discourse today, readily maintain the prick tale with their “self-certain and self-fulfilling predictions, like the ‘game over, too late’ discourse” (56). However, to accept such deadening abstract futurism and thus its championing of supremely indifferent despair is as equally senseless — and brings with it exactly the same potential for catastrophic futures — as it would be to deny absolutely the seriousness, urgency, and magnitude of the problems that confront us today.

Haraway advocates instead staying with the trouble, which she describes as “redo[ing] ways of living and dying attuned to still possible finite flourishing, still possible recuperation” (10). We all, she insists, “require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles,” a requirement that, in Staying with the Trouble, she aims to both argue and perform (4). In order to do this, she writes, we must first “look for real stories that are also speculative fabulations” (10). A somewhat vague specification admittedly, this is quickly augmented by a list of “oddkin” terms, all of which come under the order of the acronym SF: string figures, science fact, science fiction, speculative feminism, and so far. “Not in the world, but of the world,” says Haraway, the “worlds of SF are not containers; they are patternings, risky comakings, speculative fabulations” (14).

Initial troubles

Haraway’s narrative of composable and decomposable worldings brought forth through countless unaccountable multispecies players all “enmeshed in partial and flawed translations across difference” is as compelling as it is necessary (10). Before we can address Staying with the Trouble in greater critical depth, however, we must first consider two troubling textual issues, the first aesthetic and economic, the second terminological.

1. The Market Demands of Celebrity

The influence of Donna Haraway’s work across an array of disciplines and inter-disciplines has long been undeniable. Indeed, she is one of very few thinkers working in English today whom one could legitimately — that is, in a positive, non-pejorative sense — describe as a “celebrity” academic. Moreover, there are probably even fewer contemporary thinkers, in any language, who are as aesthetically and cognitively committed to design and pattern in the presentation of their work as Haraway. In the case of Staying with the Trouble, however, it seems that the demands of the latter have suffered somewhat at the hands of the former. Or, put in the language of political economy, we could say that the exchange value of “Haraway” as the name of a commodity appears to have been privileged at the cost of the use value of Haraway as thinker.

Hence, what will likely strike the reader first of all about Staying with the Trouble is its obvious imbalance, with very nearly half of the total content being made up of largely extraneous material: namely, an incredible mass of end notes, an extended bibliography, and, lastly, a whopping — and largely redundant — 32 page index covering a main text that itself covers less than 170 pages and incorporates dozens of images along the way. The likely second thing to become all too frustratingly evident to the reader — after the first dozen or so pages — is that Haraway’s “new” book is in fact a collection of six previously published stand-alone articles, and concluding with a hitherto unseen piece of “speculative” fiction. All of this is not necessarily a bad thing — extensive revision coupled with adroit use of differently focused draft versions, for example, can indeed transform a set of related yet independent articles into a dramatic and coherent monologue. Unfortunately, however, that has not been the case here.

Rather, a great deal of the same statements and descriptions are repeated again and again in every chapter, along with the same names and same references, the same intellectual debts and the same points of collaboration. Indeed, the amount of repetition found within Staying with the Trouble is largely the reason why the endnotes stretch out over sixty pages, all of which is a lot less interesting than the actual work of staying with the trouble. The trouble, one assumes, is the consequence of stand-alone journal articles being forced too violently into the generic framework of book chapters. There are times when the sheer weight of reiteration comes to sound less like an acknowledgement of comrades banded in their shared struggle and more like a branding of kinship onto others, a marking of names aimed more toward ownership and legacy. But then again, and as is well known, reiteration tends toward odd, unpredictable doings when left unchecked for too long.

With respect to repetition, moreover, the same question can be asked on a more general level, as Haraway herself makes clear: “It is no longer news,” she writes, “that corporations, farms, clinics, labs, homes, sciences, technologies, and multispecies lives are entangled in multiscalar, multitemporal, multimaterial worlding” (115). Rather, she continues, it is the details that matter, as it is the details that ”link actual beings to actual response-abilities” (115). Indeed, but this once again begs the question as to why Haraway spends so much of her latest book reiterating the former at the expense of the latter.

2. Posthuman/ism

Reiterating the position put forward in When Species Meet, Haraway again places herself in opposition to both “the Posthuman” and “posthumanism” — two distinct notions that, more often than not, she condenses into the single term “posthuman(ism).” She does this first by retroactively invoking “companion species” as conceptually opposed to “posthuman(ism),” and then with the introduction of a new term intended to signify, among other things, its antagonistic distance from all things posthuman: compost.

Critters are at stake in each other in every mixing and turning of the terran compost pile. We are compost, not posthuman; we inhabit the humusities, not the humanities. Philosophically and materially, I am a compostist, not a posthumanist. Critters — human and not — become-with each other, compose and decompose each other, in every scale and register of time and stuff in sympoietic tangling, in ecological evolutionary developmental earthy worlding and unworlding. (97)

Here, the trouble centers on just what Haraway is referring to with the term “posthuman(ism).” First of all, the conflation of “the posthuman” (considered as either an entity or an event) and “posthumanism” (understood as a position subsequent to the deconstruction of the traditional discourse of humanism) strongly suggests that, for Haraway, the two terms are synonymous, despite both terms having long served to mark sites of intense contestation across a wide variety of positions and disciplines.1 While the term for the most part remains without gloss throughout Staying with the Trouble, in the manifesto-type section that opens the first chapter there are signs that, for Haraway, “posthumanism” refers above all to Heideggerian existentialism (11).

Here, Haraway tells of being “finished” with both “Kantian cosmopolitics” and “grumpy human-exceptionalist Heideggerian worlding,” further claiming to be without any relation whatsoever to the “existentialist and bond-less, lonely, Man-making gap theorized by Heidegger and his followers” (11). In contrast to the “world-poor” condition Heidegger infamously attributes to nonhuman animals, she continues, the worlding of “the SF web of always-too-much connection” is rather “rich in world, inoculated against posthumanism but rich in com-post, inoculated against human exceptionalism but rich in humus, ripe for multispecies storytelling.” On closer inspection, however, we would do well to wonder just how anti-Heideggerian we really are here. First of all, the strain of existentialism that, at least from this very brief description, would seem to ineluctably stain every notion of the posthuman, sounds far more akin to Antoine Roquentin’s world of nauseous isolation as described by Jean-Paul Sartre than it does to anything put forward by Heidegger.2 Yes, ontological difference for Heidegger does indeed constitute and, in so doing, privilege the human as Dasein and, moreover, it does so at the cost of relegating every other living being to the vaguely articulated status of “poor-in-world.” On the other side of the coin, however, is that with his rigorous articulation of radical new concepts such as the structure of significance, of being-open, and of a calling forth into being that is simultaneously a being-thrown, Heidegger dramatically informed and transformed our understanding of being-in-the-world. Moreover, he continues to do so, as is the case here when, writing of the capabilities of pigeons that so impress and surprise their human kin, Haraway notes that human beings

often forget how they themselves are rendered capable by and with both things and living beings. Shaping response-abilities, things and living beings can be inside and outside human and nonhuman bodies, at different scales of time and space. All together the players evoke, trigger, and call forth what — and who — exists. (16)

“I am a compostist, not a posthumanist,” Haraway declares, “we are all compost, not posthuman” (101-102). A better idea, I suggest, would be to stay with all the troubling humus and hubris of the posthuman, to continue taking the trouble with posthumanism for some while yet — com-post, that is to say, with-post. At the very least, this “having finished with” Heidegger (and with Kant before him) suggests a symbolic setting-free that accords rather with something like a “near-utopianism” that can be sensed throughout Staying with the Trouble, of which more later.3

Three Tales of Trouble

The heart of Staying with the Trouble can be found at the various intersections and crossings-over of three different stories that speak themselves in three mostly distinct genres. First, now as then, is the prick tale of Humans in History. Second, comes the nested narrative — and sublime quietism — of the Anthropocene. And, third, stories that somehow narrate outside the first and somehow think beyond the helpless despair of the second — stories of a living future for living in the Chthulucene, and where, in the end, we will ultimately encounter Camille.

1. The prick tale

“Tool, weapon, word,” writes Haraway, “that is the word made flesh in the image of the sky god; that is the Anthropos” (39). Much of earth history, she writes, is a Man-made tragedy “told in the thrall of the fantasy of the first beautiful words and weapons, of the first beautiful weapons as words and vice versa” (39). This is the prick tale, featuring but a single actor in the role of hero and world-maker engaged throughout in murderous conquest that allows of space for nothing else and nothing more: “All others in the prick tale are props, ground, plot space, or prey. They don’t matter; their job is to be in the way, to be overcome, to be the road, the conduit, but not the traveler, not the begetter” (39). In Staying with the Trouble, Richard Dawkins’s “later sociobiological formulations within the Modern Synthesis, The Selfish Gene” (62) serves as an exemplary moment in its ongoing action-movie plotline.

Working against this simplistic quest narrative, Haraway poses SF writer Ursula K. Le Guin’s “carrier bag theory of narrative” and what she calls the “Gaia stories” of prominent social theorist Bruno Latour. As regards the latter, however, Haraway is right to maintain her reservations with respect to Latour’s reliance on “the material-semiotic trope of trials of strength” (42), not the least of which being its obvious availability for appropriation within the prick tale quest narrative, and within that of neo-Darwinist sociobiology in particular. At this point, Haraway displays her talent for close textual analysis — albeit a talent far more in evidence in her early works — in tracing back Latour’s structuring trope to its foundation in the work of political theorist Carl Schmitt. As Haraway astutely remarks, “Schmitt’s enemies do not allow the story to change in its marrow; the Earthbound need a more tentacular, less binary life story. Latour’s Gaia stories deserve better companions in storytelling than Schmitt. The question of whom to think-with is immensely material” (43).4 Also interesting here is that, while Haraway reiterates this last sentence any number of times over the course of the Staying with the Trouble, only here does it take on weight and meaning, as only here it is sufficiently contextualized to become something more than a simple slogan.

2. The Anthropocene

According to Haraway’s excellent analysis, “the Anthropocene” understood in terms of an epochal period of time on earth is essentially a continuation of the prick tale of Humans in History by way of a nested millenarian narrative that lends itself all too readily “to cynicism, defeatism, and self-certain and self-fulfilling predictions, like the ‘game over, too late’ discourse I hear all around me these days” (56). For all of that however, continues Haraway, the idea of imminent catastrophe is hardly new – and this is a hugely important point: “disaster, indeed genocide and devastated home places, has already come, decades and centuries ago, and it has not stopped” (86). That we “stay with” such trouble is at the very center of Staying with the Trouble insofar as resurgence “is nurtured with ragged vitality in the teeth of such loss, mourning, memory, resilience, reinvention of what it means to be native, refusal to deny irreversible destruction, and refusal to disengage from living and dying well in presents and futures” (86). Such are the stories of living and dying in what, as a far better alternative to the misplaced but by now entrenched terms Anthropocene and Capitalocene, Haraway gives the name “the Chthulucene.”

Haraway is right to foreground the need to think of the Anthropocene not as the name of an epoch, but rather as a boundary event akin to the K-Pg boundary between the Cretaceous and the Paleogene periods. “The Anthropocene,” she insists, “marks severe discontinuities; what comes after will not be like what came before” (100). Of particular interest for Haraway, however, is just why it should be that the epochal name of the Anthropocene imposed itself in the way it did at just the time “when human exceptionalism and the utilitarian individualism of classical political economics become unthinkable in the best sciences across the disciplines and interdisciplines” (57). Could it … perhaps, just perhaps … be that the Anthropocene is not in fact a guarantor of the end of the world as a fait accompli but simply a last desperate fable along the prick tale of Humans in History, simply “the last gasps of the sky gods” (57)? And again, what is simple sloganeering elsewhere here becomes a thing of weight and meaning: “It matters which thoughts think thoughts” (57).

3. The Chthulucene

Despite Haraway’s claim that, as words go, the inelegant Chthulucene is in fact quite “simple” (2), the term — all questions of pronunciation and catchiness aside – is not without its issues. As a term, “Chthulucene” would seem to constitute a clear and obvious reference to the fiction of H. P. Lovecraft in general, and to his 1928 short horror classic, “The Call of Cthulhu” in particular. However, at the very outset what for Haraway must be made absolutely clear is that “Lovecraft’s misogynist racial-nightmare monster Cthulhu” has no role to play here whatsoever (101, 174n4). In other words, it is imperative for Haraway that, upon the introduction and every subsequent reiteration of the term “Chthulucene,” we somehow not allow what is its sole, blaringly obvious reference to impact upon our relation to the word. In a move that can hardly be described as helpful, Haraway signals this utter absence of relation by way of an extremely subtle change in spelling (a difference so subtle, it should be noted, that we must be parenthetically reminded to take note of upon each appearance). Hence, Haraway’s entirely discrete conceptual beast is properly the Chthulucene, as opposed to that founded upon the Lovecraftian term “Cthulhu,” which would have yielded instead the noun Cthulhucene. It’s just so obvious now, right? Problem solved. All facetiousness aside, however, I am baffled as to why Haraway would select for a central concept of the book — perhaps the central concept, and most certainly its unifying term — a term that refers uniquely and explicitly to the Lovecraftian oeuvre, only to then deny the sole significance it necessarily brings with it? Just what is going on here? Is the shift from “Cthulhu” to “Chthulu” at once magical spell and magical spelling by which the monstrous anxiety of influence can apparently be rendered inoperative, or at least inapparent? It is difficult to understand exactly what is at work here, and what is at play. What appears and what disappears, and what is being made to appear and what is being made to disappear?

The story as Haraway sees it is that she “rescues” the Cthulhu from Lovecraft in order to make it available for other stories, and marks this liberation from Lovecraft’s patriarchal mode “with the more common spelling of chthonic ones” (174n4). In this way, she argues, are unveiled diverse undulating and ongoing “tentacular powers and forces and collected things with names like Naga, Gaia, Tangaroa (burst from water-full Papa), Terra, Haniyasu-hine, Spider Woman, Pachamama, Oya, Gorgo, Raven, A’akuluujjusi, and many many more” (101).

Sounding a little vague and somewhat utopian at first, Haraway begins to articulate the new contours of the Chthulucene by first making very clear just what it is that we must not be doing, or must not continue to do, if we are to have any hope of staying with the trouble: this is not an argument for cultural looting; it is not about raiding situated indigenous stories for their use as resources for harnessing the “woes” of colonizing projects and peoples; and it is not “a way to finesse the Anthropocene with Native Climate Wisdom” (87). From the other side, meanwhile, it is not the answer to anything and everything: it is not about playing games for “universal oneness,” and it is not a “posthumanist solution to epistemological crises.” Finally, it is not a general program that, if followed to the letter, promises a solution to any given particular: Staying with the Trouble, as is the case also for any one of its exemplary narratives, is not a general model for collaboration. It is not “a primer for the Chthulucene.”

So, after learning of all that it is not, what exactly is going on here? How might we set out “to learn somehow to narrate — to think — outside the prick tale of Humans in History” (40)? The answer, posits Haraway, is sympoiesis.

Staying with the Trouble: Sympoiesis

Demon Familiars

In a move that will be familiar to readers of her previous books, Haraway narrates the story of the Chthulucene by way of figures that are at once real and imagined: material-semiotic. Christened “demon familiars” here, previous figures of Haraway have included a certain post-gender cyborg, a Harvard mouse with an activated oncogene and, more recently, a protozoan by the name of Mixotricha paradoxa. In Staying with the Trouble, however, the importance of such figures to the ongoing ebullience of worlding feels immeasurably greater, as too does the urgency with which they are required (the latter, no doubt, playing a major role in the former): “We need another figure,” she writes, “a thousand names of something else, to erupt out of the Anthropocene into another, big-enough story” (52).

Perhaps, then, Haraway can be forgiven for the somewhat obvious instrumentality in her use of another demon familiar and fellow North Central California resident — the spider Pimoa cthuluhu — as a stepping stone on the way to the latest figure of privilege: “Bitten in a California redwood forest by spidery Pimoa chthulhu [note spelling],5 I want to propose snaky Medusa and the many unfinished worldings of her antecedents, affiliates, and descendants” (52). From the Greek Μέδουσα, meaning “guardian’ or “protectress,” Medusa is a powerful winged being with living snakes for hair and possessing a gaze with the power to turn its recipient to stone. Moreover, as the only mortal member of the race of Gorgons, Medusa is a chthonic being without proper genealogy, of “no settled lineage and no reliable kind (genre, gender)” despite being “figured and storied as female” and with a reach that is “lateral and tentacular” (53-54). In this, Medusa is a figure and the figure here — one of a thousand names — of sympoiesis.

Perhaps, just perhaps, writes Haraway, Medusa might “heighten our chances for dashing the twenty-first century ships of the Heroes on a living coral reef instead of allowing them to suck the last drop of fossil flesh out of dead rock” (52).

Sympoiesis

Haraway offers less a rigorous accounting of “sympoiesis” as a concept, and more an exuberant surging and outpouring of synonyms, likenesses, kinships, and recursive patternings. We can, however, pick out three key aspects of sympoiesis. First, and most important, is an underlying relational ontology: entities are constituted by “an expandable number of quasi-collective/quasi-individual partners in constitutive relatings; these relationalities are the objects of study. The partners do not precede the relatings” (64). Second, and following from the first, any research that takes substance as prior to relation will necessarily fail in any attempt aimed at “studying webbed inter- and intra-actions of symbiosis and sympoiesis.” And third, the generative nature of sympoiesis is made possible by its recursive structure — it is the passing of “relays again and again … that make up living and dying” (33).

Familiarly Demonic

With all the talk of “abyssal and dreadful graspings, frayings, and weavings” (33), of sympoiesis understood as “alignment” and not inheritance, and of chthonic entities as beings lacking proper genealogy and settled lineage, one cannot help but wonder at the glaring absence of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari throughout Staying with the Trouble, and in particular their hugely influential notions of alliance, genealogy, becoming, demonic animals, and assemblage. Haraway, for example, proposes that we replace the term “beings” with “holoents” (or “holobionts”), meaning “symbiotic assemblages at whatever scale of space or time, which are more like knots of diverse inter-active relatings in dynamic complex systems” (60). At this point, one can only assume that Deleuze and Guattari are still a little too demonic — or differently demonic — as yet for Haraway, given her brief but scathing dismissal in When Species Meet and elsewhere. That said, one hopes that Haraway’s renowned generosity of practice might well return her to Thousand Plateaus at some time in the future — a sympoietic engagement that would likely prove to be extremely productive indeed.

In the same vein, one can wonder about potential results of a closer engagement with both Nietzsche’s will to power and Spinoza’s conatus. In opening the chapter on “Sympoiesis,” for example, Haraway suggests that critters become-with each other perhaps “as sensual molecular curiosity and definitely as insatiable hunger, irresistible attraction toward enfolding each other is the vital motor of living and dying on earth” (58). Haraway is very unclear as to whether what is being described here is in fact a drive — especially given the use of terms such as “insatiable” and “irresistible” in this context, as this would seem to return us to the deeply problematic issue of the instinctive, the driven, and the mechanistic, of the vitalism of program and instinct and of the paradoxical entity that would be a “vital motor.”

Material Semiotics and Life at the Limit

This paradox of a “vital motor” possibly plays an obscure role in Haraway’s extremely important notion of “material semiotics,” insofar as the latter would seem to open up the idea of “living” far beyond its traditional restriction to that of individual biological organisms. Material semiotics, she writes, “is exuberantly chemical; the roots of language across taxa, with all its understandings and misunderstandings, lie in such attachments” (66). For Haraway, “critters” are always dynamic multipartnered entities across every scale and time, and theoretically without privilege. Hence the need to ask how multicellular partners in the symbioses affect the microbial symbionts, and not just vice versa: “at whatever size, all the partners making up holobionts are symbionts to each other” (67).

Despite this, however, it remains unclear whether Haraway includes within her definition of critters — holobionts, holoents — such multipartnered relatings as would traditionally be defined as nonliving entities, that is, “simple” material objects, mere “things.” At times the answer appears to be yes: “Critters — human and not — become-with each other, compose and decompose each other, in every scale and register of time and stuff in sympoietic tangling, in ecological evolutionary developmental earthy worlding and unworlding” (97). At other times, however, it would seem not to be the case: “Plants are consummate communicators in a vast terran array of modalities, making and exchanging meanings among and between an astonishing galaxy of associates across the taxa of living beings. Plants, along with bacteria and fungi, are also animals’ lifelines to communication with the abiotic world, from sun to gas to rock” (122).

Blueprint for Global Change, Salve for the Suburbanite, Academic Ego-Aggrandizement

In the end, Staying with the Trouble offers its readers an almost endless series of fascinating, inter- and intra-linked stories — of the Crochet Coral Reef, of the Madagascar Ako Project, of the console game Never Alone, and of many more stories, and of so many still to come. However, one question haunts every one of these stories: Can such necessarily local commemorations ever translate into global change? Take the tale of the Melbourne pigeon loft, for example: can and do such tales ever amount to more than self-serving narratives of middle-class philanthropy? Can and do they escape charges such as idealism and naivety, given the notion of staying with the wider trouble, such as the fate of aborigines? Or are they only pocket utopias, mere academic compositions? It is a question, moreover, of which Haraway is fully aware: “the municipal pigeon tower certainly cannot undo unequal treaties, conquest, and wetlands destruction, but it is nonetheless a possible thread in a pattern for ongoing, noninnocent, interrogative, multispecies getting on together” (29). Such a practice of “cultivating response-ability,” she further argues, “is not a heroic practice … is not the Revolution … is not Thought. Opening up versions so stories can be ongoing is so mundane, so earth-bound. That is precisely the point” (130).

Quite so. But this still does not answer our question: can such a resolutely mundane, so decisively earth-bound a practice, ever bring with it potential for change on a global scale? Or does it rather narrate the impossibility of any such practical potential? Responding to the question of a self-serving salve,Haraway claims instead that the processes of symbiogenesis or sympoiesis are necessarily infectious (64) — an infectiousness that therefore has the potential to be world-changing. But are they really, in fact, infectious, as Haraway claims: “Companion species infect each other all the time. Pigeons are world travelers, and such beings are vectors and carry many more, for good and for ill. Bodily ethical and political obligations are infectious, or they should be” (29). They are infectious, or they ought to be infectious? To be, or to ought to be: that is indeed the question, but on this point, at this point, Haraway hesitates. Only at the very end, with the introduction of “The Camille Stories,” does Haraway at last engage with this question of the relation, or otherwise, of local and global.

Camille began life at a writing workshop at a colloquium at Cerisy in 2013, in which participants were collectively asked “to fabulate a baby, and somehow to bring the infant through five human generations” (134). The first iteration (“Camille 1”) is born in 2025 and the last (“Camille 5”) dies in 2425, during which time the global human population continues to increase to a high of ten billion in 2100, before then declining to a stable three billion by 2400. As one of the conditions for a sustainable global future, Haraway writes, this massive reduction in the overall number of human animals is initially made possible through a “new” collective practice among small, close-knit communities of birthing babies bonded with animal symbionts. Camille 1 is one of the first of these, born in symbiosis with a Monarch butterfly and, at least in one of our futures, ushering in a new age of kinship, intimacy, and response-ability.

Ultimately, the potential for global change from local commemoration can be located here, in this speculative account of a future history. A “story, a speculative fabulation,” and, according to Haraway, “a relay into uncertain futures” (134), the stories of Camille offer an account of — and attempt to account for — a four-hundred-year period bearing witness both to the end of capitalism (and thus the Capitalocene) and the inauguration of the Chthulucene. Camille, writes Haraway, “is a keeper of memories in the flesh of worlds that may become habitable again. Camille is one of the children of compost who ripen in the earth to say no to the posthuman of every time” (134). A story, then, a fabulation; but also manifesto and blueprint.

And so, in the end, it matters more how we might we read this new genre of manifesto — it matters, in Haraway’s words, which thoughts think thoughts and what stories we use to tell stories. Is this utopian SF? Does it bespeak of Idealism, of naivety and of the Ego? Do we see in Camille the vision of Haraway as New (Age) Earth Mother? And is this even fair criticism? Or else prick thinking? And can this even be answered in accordance with the framework that Haraway sets out — a kind of unfalsifiability that it itself denounces as irrelevant?

“Tool, weapon, word,” we recall, “that is the word made flesh in the image of the sky god; that is the Anthropos” (39). And “Camille” too is of course tool, weapon, and word, one purposefully aimed at crafting — at creating, speculating, constructing — a word and a world to be made flesh in the image of the chthonic god. But does Camille offer anything beyond a simple change of name alone? Is this perhaps a change of genre, but not of narrative structure? And how can we be sure that Haraway’s tentacular “Chthulu” is not, in the end, Lovecraft’s deeply patriarchal prick? After all, the sky god too has a thousand names.

In the end, our question can be further concentrated: is it possible to propose — to speculate — a figure of sympoiesis? Or is it not rather the case that sympoiesis is the very impossibility of being named, of being figured (out) in advance?

Notes

1. Oddly, elsewhere in Staying with the Trouble Haraway appears clearly cognizant of the need to differentiate between the two distinct concepts, noting that “posthumanists” constitute “another gathering altogether” than those of the “Posthumans” (50). Just why Haraway should abruptly bestow capital letter status upon the latter term remains unclear.

2. See Jean-Paul Sartre Being and Nothingness [L’Être et le néant] (1943) and Nausea [La Nausée] (1938). Sartre’s telling philosophical tales is also germane to the issues in Haraway’s case of inheritance, alliance, alignment, and legacy.

3. The notion of “a near-utopianism” in relation to Haraway’s oeuvre comes initially from Istvan Csicsery-Ronay’s review of When Species Meet entitled “After Species Meet” in which he writes of “the erstwhile Human” becoming for Haraway “a dynamic, tumbling network of living relationships” that includes “a near-utopian web of scholars and fellow-teachers constantly supplying new energies to each other” (n.p.). In Humanimalia: A Journal of Human-Animal Interface Studies 1.2 (2010): 145.

4. In my book Zoogenesis: Thinking Encounter with Animals (London: Pavement Books, 2014), I argue that Schmitt’s Friend/Enemy dichotomy as and at the origin of the nation-state is nothing short of the political logic of genocide in its purest form (220-230).

5. And note the perceived need, on Haraway’s part, to note the spelling correction/impropriety.