Our Funnaminal World

Humanimalia 16.1 (Winter 2025)

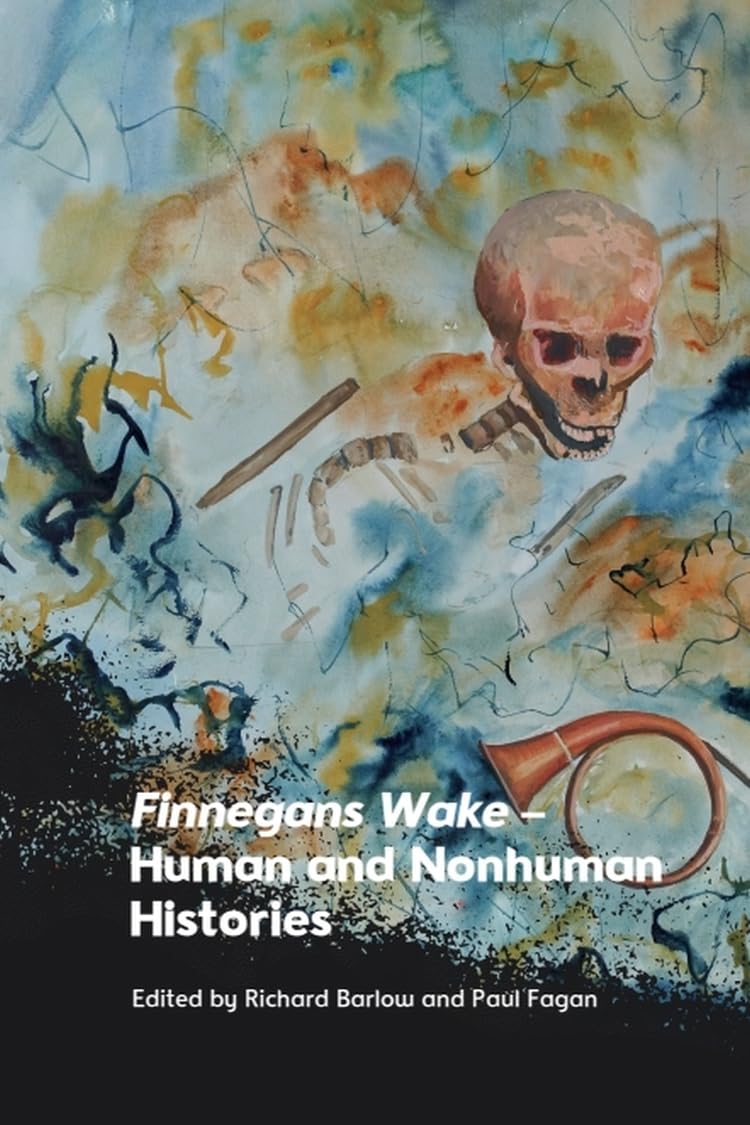

On the cover of Finnegans Wake — Human and Nonhuman Histories is a painting from Carol Wade’s series The Art of the Wake. A human skull and spine emerge from a gaseous and squiggly miasma, a mess of nonhuman stuff. A post horn suggests that this might be the moment of resurrection, of Finnegan rising from the grave in response to Gabriel’s horn on Judgment Day. But if this is Tim, or Finn, or HCE or any of his other avatars, then it is startling that he appears as bare bones rather than robed in ruddy flesh. In Wade’s image, resurrection is more earthy and nonhuman than it is typically conjured elsewhere. In the ballad from which Joyce’s book takes its name, whiskey splashes on Tim, resurrects and revives him, and he’s quickly ready to drink and dance again. Unlike the ballad’s spry (for a recent corpse) and thirsty Finnegan, Wade’s skull and spine leave viewers to wonder how much of the human is left in these human bones. Where is the human in a fragment of skeleton? And was there something nonhuman that skulked within this erstwhile human all along, just waiting to get out? Wade’s artwork responds to Finnegans Wake’s powerful imagery, what Enda Duffy calls Joyce’s “will to visualize.”1 For Duffy, Joyce is not a subverter of authorities or a transgressor of boundaries but a maker of images. This is nowhere more the case than in Finnegans Wake, which we might regard as a unique resource for generating startling images, ideas, and visions of the human relative to the nonhuman.

Finnegans Wake — Human and Nonhuman Histories integrates historicist approaches to Finnegans Wake with nonhuman-centred ones such as animal studies, ecofeminism, sound studies, petroculture studies, and the blue humanities. As its title suggests, the book’s goal is to consider how Finnegans Wake represents the material stuff of human histories even as it looks beyond these histories to what Joyce calls “all this our funnaminal world” (FW 244.13). Editors Richard Barlow and Paul Fagan acknowledge that historicist and nonhuman-centred approaches sit uneasily together. Historicist practice is often human-scaled and human-centred while non-human-centred approaches seek scales and focuses beyond the human. Rather than trying to reconcile these “divergent attitudes”, however, the volume’s contributors intend to “lean into” and “explore the tension” between, on the one hand “the ideological and material contexts of a specific historical moment of transformation”, and, on the other, “a unique glimpse of the movements of time, life and death that outscale the human and are thus irreducible to notions such as the nation state or politics” (10).

Joining and attempting to reconcile historicism and non-human-centred approaches, Barlow and Fagan argue that Finnegans Wake represents human and nonhuman life as bound through “interdependent histories” (2). The Wake (as Joyce readers often refer to it) destabilizes “ontological boundaries” between humans and nonhumans as well as anthropomorphic historical and literary narratives that support and reinforce such boundaries (3). For the editors and contributors, Joyce’s book engages human history extensively but adopts “a nonhuman vision” to understand it. Linear history, finished being, and the traditional humanist subject are de-emphasized in the Wake in favour of cyclicity, becoming, and “discursive-material assemblages” (6). Finnegans Wake “blurs and transgresses” the limits of human, animal, nature, and writing itself (4–5). Barlow and Fagan also offer the Wake as a “vital site for reflecting on literature’s role” in thinking about the exigencies of the Anthropocene “in a twenty-first-century context” (11). They contend that by engaging in planetary (not just human) historiography and by representing more-than-human material, geological, and biological processes, the Wake allows readers to envision different, potentially ameliorative ways of living on Earth (11).

The topics of the volume’s twelve essays — which include peat (Katherine Ebury), storms (Katherine O’Callaghan), river women (Shinjini Chattopadhyay), leaky bodies (Laura Gibbs), lakes (Richard Barlow), skin and hides (Paul Fagan), wolves and werewolves (Annalisa Volpone), mourning (Christopher DeVault), genes and memes (Sam Slote), atoms (Ruben Borg), sound (Michelle Witen), and labour (Ronan Crowley) — suggest the Wake’s sheer diversity and hint at the huge range of its nonhuman topics. The essays succeed in exposing tensions in historicist approaches to the text’s more-than-human world. Most of the essays depart from the anthropocentrism with which historicism is often practiced. It’s encouraging to see the nonhuman predominate in these essays, which are guided by the belief that Finnegans Wake “provides a textual experience of the intertwined lives and fates of humans, animals, technologies and environments across diverse histories and shared futures” (16), as Barlow and Fagan put it in the Introduction.

It’s also clear that the collection construes the nonhuman very broadly. This is a strength, as it productively decentres the human, but also a weakness because when the nonhuman is so broadly defined that an essay like Witen’s, which reaches the nonhuman through new materialism and would be at home in a sound studies reader, abuts an essay like Crowley’s, whose purchase on the nonhuman is through Joyce’s “inhumanity” to his friends and would be at home in a biographical study of Joyce, it erodes a sense of common ground and common project.

I wished, too, for the authors to have reflected more on how their adopted nonhuman-centred approaches expose shortcomings in historicist theory. I also wished for more reflection on how nonhuman-centred approaches might demand alternatives to the sturdy but predictable historicist formula that weaves together context, a neglected document, event, or phenomenon or two, and a short example from the literary text. Cultural and intellectual context can often be such a powerful determinant for historicists that they are prone to describe what they encounter in terms of the already known, and this can be perilous for a text as sprawling and searching as the Wake. For example, the essays tend to favour readings in which Finnegans Wake is said to illustrate, exemplify, or foresee some contemporary viewpoint. For Katherine Ebury, whose concept of an “energy unconscious” (22) offers a useful angle into Joyce’s nonhuman representations, Finnegans Wake “anticipates a contemporary understanding of petrocultures and the climate crisis” (33). For Laura Gibbs, who compellingly reads bodies as ecosystems (72), the Wake “reflects […] recent attitudes” toward gender (76), is “in line with” and even “exemplifies” (79) the hydrofeminism of Astrida Neimanis. Despite the sharp analyses offered in these and other essays, it is disappointing how often Finnegans Wake turns out neatly to presage a contemporary view, as though its power was in having foresight about our contemporary truths, rather than in being visionary in ways that could possibly help us out of our own reigning truisms.

Often, the essays rely on a familiar historicist dialectic of transgression versus authority, namely what Alan Liu, in a classic critique of new historicism’s form, calls the Disturbed Array versus the Governing Line.2 In this case, the logic at work in the essays’ arguments positions Joyce’s work as subverting a posited authority. For example, traditional ways of distinguishing between the human and the nonhuman or differentiating between species might be established by the critic as an authority that Finnegans Wake somehow uproots. For Paul Fagan, who fascinatingly explores connections between topography and history, skins and hides in the Wake are “liminal surfaces” (99) where the “limits of the human and the nonhuman are […] continuously transgressed, multiplied and redrawn” (100). For Annalisa Volpone, who explores unexpected and suggestive connections between animals and shamans, Shem is a wolfish “hybrid” (116) who, as “artist and werewolf […] incorporates the transformative and boundary-breaking power of erasing traditional distinctions between species” (128). For Shinjini Chattopadhyay, who innovatively reads ALP through the lens of blue humanities, ALP, simultaneously woman and water, “intermixes human and nonhuman realities” (50) in the face of “colonialist oppression” (52), and “subverts British colonial hegemony” (61). I found myself wondering what it would mean to bring together non-human-centred criticism and historicism without such a pattern. I also wondered whether Finnegans Wake itself, in which we seldom find a clear authority figure and transgressor who do not eventually “swop hats” (FW 16.8), might have offered pathways out of the historicist authority–subversion binary opposition.

While many of the essays adopt a clear historicist formula, there are also rewarding moments that look beyond the Wake’s purported transgressions and pat contemporaneity and attend to its will to visualize with a freshness and creativity that matches Carol Wade’s painting. When the writers allow Joyce’s images to point toward the unknown, when they follow wherever they lead, the essays are at their most creative and indeed Wakean. I’ll cite just two examples. In “Impossible Mourning in Finnegans Wake”, Christopher DeVault attends to the novel’s “mournful identities that combine human and nonhuman elements […] destabilising the boundaries between self and other that mourning ostensibly enforces” (132–33). DeVault points toward how the Wake “creates a commemorative alternative to […]simplistic performances of complete mourning” (138) by exploring Biddy Doran’s “hennish mourning” (140) and her “fowlish perspective”. DeVault shows that Joyce represents Biddy’s perspective on death and mourning not just as an alternative to but also as “more meaningful than that of the human citizens” (141). We see how the Wake does not just blur or transgress, but also offers a creative alternative, a non-anthropocentric vision of death and mourning. Such a view of death and mourning might indeed help us to think about living with and among other animals in more harmonious and companionable ways, for instance, by helping us to envision our deaths outside of traditional humanist ways of making sense of both human death and life.

Similarly, in “‘singsigns to soundsense’: Music and the Nonhuman in Finnegans Wake”, Michelle Witen argues that “musical terminology in the Wake negotiates between human and nonhuman ‘sound’, showing the figure of the human moving from dissonance to harmonic resolution via its interactions with the more-than-human” (181). To be sure, we are told that the Wake’s presentation and representation of sound “questions and destabilises the boundaries between the human and the nonhuman” (182) and that it “exemplifies” (184) ideas about sound articulated by contemporary scholars. But Witen masterfully analyses the harmony, discordance, concord, and resolution of sound in Finnegans Wake. Witen glosses the line, “And all, hee hee hee, quaking, so fright, and shee shee shaking. Aching. Ay, ay” (FW 395.24–5) as at once the sound of ALP and HCE’s creaking conjugal bed and as “aurally approximate” (hee, shee, ay) to the musical triad H-C-E in German musical notation (190). By carefully and elegantly attending to such nonhuman sound images in the Wake, Witen makes readers hear them and know “the resonances, harmonies, disharmonies, dissonances and concordances through which Joyce negotiates and crosses the divide between the human and the nonhuman” (185). Witen shows that sound, music, and noise in the Wake have a surprising materiality that connects human and nonhuman bodies.

For those who wish to build on the topics and arguments of this collection, Finnegans Wake poses ongoing challenges for historicism and fresh opportunities for non-anthropocentric thought. It shakes contexts and mutates ideas. It pushes towards the unknown and the unknowable. It is capacious and visionary; it dissatisfies us with what we know. This is most evident in the act of reading the Wake, where open-minded confusion is more likely to be the abiding spirit rather than explanation within a historical context or explication via contemporary theories. Especially if we are trying to peer beyond the human, historical and theoretical avenues of explanation will be insufficient — even in a rich volume such as this one, which otherwise offers a nonhuman cornucopia — unless the Wake is also allowed to erode the very historical and theoretical toeholds we think we have on it. The Wake’s potential for thinking beyond anthropocentrism may lie not in what it anticipates or transgresses but in showing us, through its creative routes into the not-yet-conscious, what we have not anticipated. When confronting the changes to our Earth or rethinking our lives with and among the other Earthlings, Finnegans Wake can at least remind us that we may not yet have the best, or often even adequate means of telling ourselves these stories.

Notes

Enda Duffy, “The Happy Ring House”, in Joyce, Benjamin and Magical Urbanism, ed. Maurizia Boscagli and Enda Duffy (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2011), 176.

Alan Liu, “The Power of Formalism: The New Historicism”, ELH 56.4 (1989): 721–71.