Go Panda Go!

The Invention of the Panda Circus and Its Exhibition in China–Japan Municipal Diplomacy

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.22582

Keywords: The Giant Panda, Animal Diplomacy, China–Japan relations, Animal Circus, Emotional Labour, Animal Communication and Media

Email: tracyyzh@yorku.ca

Email: nagayama.chikako.s9@f.mail.nagoya-u.ac.jp

Humanimalia 16.1 (Winter 2025)

Abstract

This article examines the invention and exhibitions of the panda circus to explore the political, economic, and cultural influence of the giant panda on China–Japan diplomacy and the transnational cultural economy. Using oral history interviews and archival materials, the authors explain how, in 1981, a giant panda named Wei Wei became China’s first panda entertainer in Japan, embarking on a cross-country tour supported by friendship-city agreements and grassroots friendship movements. By discussing Wei Wei’s unexpected and sometimes ferocious responses to human demands, as well as Japanese media reporting on his “rebellion”, the authors show how Wei Wei’s behaviour raised Japanese public awareness of the giant panda’s individuality and agency. The circus tour not only facilitated municipal-level China–Japan relations but also generated a new mode of anthropomorphizing the giant panda—one that challenged consumerist representations and helped Japanese audiences recognize the giant panda’s suffering. The authors argue that Wei Wei’s “rebellion” disrupted human political expectations and economic transactions in this episode of China–Japan diplomacy, contributing to a re-envisioning of bilateral relations beyond a strictly political-economic framework. Overall, the article offers an interdisciplinary, trans-Asia approach that explores the intersections of animal agency, emotional labour, international relations, media, and performance.

On the evening of October 28, 1972, a pair of giant pandas, Kang Kang (康康) and Lan Lan (兰兰), arrived at Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport.1 When the covers of their transport crates were lifted, a crowd of reporters and waiting parents and children rejoiced at the sight of the furry newcomers. Yet all they could see was the motionless hindquarters of one panda; the other briefly pressed his nose against the metal bars, glancing toward the noisy onlookers before turning away and ceasing to engage.2

At the welcome ceremony in Ueno Zoological Gardens, Japanese politicians delivered public speeches before a well-seated audience. A group of smiling Chinese delegates walked onstage to receive bouquets from uniformed children. Moments later, an orangutan — held by a handler — pulled a string to open a round piñata, unfurling a banner that read “Welcome the Giant Pandas, Kang Kang and Lan Lan”.3 This performance created the impression that the Japanese government, the Japanese public, and even the zoo’s nonhuman animals were happily receiving the pandas as new residents. In reality, zookeepers reported that Kang Kang and Lan Lan paced nervously inside their lodgings, surrounded by excited human spectators.4

From the airport to the zoo, humans and nonhuman animals together staged the spectacle of so-called “panda diplomacy” to advance relations between Japan and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). After the Second World War, two political factors primarily impeded the normalization of China–Japan relations. First, the Japanese government maintained formal diplomatic ties with the Republic of China in Taiwan (ROC). Second, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was dominated by pro-US politicians who opposed establishing formal communications with the PRC.5 Nonetheless, Japanese pro-PRC politicians and non-partisan organizations attempted to build informal trade and political connections between the two countries. For example, they facilitated the signing of the Sino–Japanese Long-Term Trade Agreement and collaborated with the PRC government to repatriate Japanese war prisoners and orphans.6 These efforts, however, were frequently disrupted by political instability within both Japan and China.7 Only in the autumn of 1972 — after the PRC’s admission to the United Nations and former US President Richard Nixon’s visit to Beijing — did the Japanese government begin to pursue a more proactive approach to reconciliation. On 29 September 1972, Japan’s Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei (田中角栄) signed a joint communiqué with the Chinese leadership to normalize China–Japan relations. The arrival of Kang Kang and Lan Lan thus marked the beginning of a new chapter. In a public announcement, former cabinet secretary Nikaido Susumu (二階堂進) described the pair as “a gift from the Chinese people to the people of Japan”.8 Yet during this diplomatic mission, the pandas’ reluctance to engage with their human audience also reveals the often-overlooked agency of animals within human-centred international diplomacy.

The literature further suggests that the giant panda not only shaped public discourse on Chinese–Japanese friendship but also stimulated new forms of cultural production and consumption in Japan. Although panda-themed merchandise had already gained popularity after Emperor Showa met Chi Chi, the London Zoo panda, in October 1971,9 the often-underwhelming encounters between Ueno Zoo visitors and the live pandas intensified consumer demand for panda-themed goods.10 Situated at the intersection of animal diplomacy and media studies, this article examines the political, economic, and cultural influence of giant pandas in international relations and in a Chinese–Japanese transnational cultural economy by analysing the invention and exhibitions of the “panda circus”.

Like other animal circuses, the panda circus was a human–animal co-performance in which a giant panda and a handler manipulated props, interacted with each other, and carried out prescribed movements onstage.11 Generally, circus animal acts involve a sequence of behaviours learned offstage, combined with the human co-performer’s acting, which clarifies the dramatic narrative for the audience.12 In 1975, the state-run Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe (hereafter SAT) presented the first panda circus at the Shanghai Indoor Stadium. The performer, Wei Wei (伟伟), was a two-year-old male giant panda who, together with his co-performer Lu Xing Qi (陆星奇), continued to appear in numerous venues until Wei Wei’s death in 1992. Besides Wei Wei, several other pandas were also trained to perform publicly, including Jiao Jiao (娇娇), the SAT’s second panda; Ying Ying (英英) of the Wuhan Acrobatic Troupe;13 and Basi (巴斯) of Fuzhou Panda World.14 By the end of 2010, however, panda circuses had largely disappeared due to tightened policy restrictions in the PRC and pressure from global animal-rights movements. Throughout their brief history, all panda performers toured abroad to promote China and entertain overseas audiences, yet no academic research has explored the political, economic, and cultural implications of this distinctive form of animal diplomacy. This article introduces the history of the panda circus to an international scholarly readership.

From 8 January to mid-May 1981, the SAT toured Japan, delivering 108 performances in fourteen cities and towns. Wei Wei was the main attraction and became a darling of the Japanese media. How did a live panda become a circus performer and collaborate with his human associates onstage? What did the inclusion of a giant panda mean for generating emotional encounters between Japanese audiences and Chinese performers during this phase of China–Japan relations? And to what extent did the panda circus help raise awareness of wildlife protection in Japan?

To answer these questions, we employed several historical methods, including archival research and oral-history interviews. First, in 2015, one of the authors visited the SAT and interviewed Wei Wei’s handler, Lu Xing Qi, to learn about Wei Wei’s training and the troupe’s 1981 Japan tour.15 Oral history helps recover material about Wei Wei’s intimate relationship with his human collaborators. Lu’s accounts provide “reminiscences, descriptions, and interpretations of events”16 that are often absent from official records, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of how individuals such as Lu conceived human–animal relations within a specific political and cultural context. Second, we consulted primary and secondary materials from China, Japan, Canada, and the United States. At the SAT, interlocutors also provided internal documents on the historical origins and development of the panda circus. Using both Lu’s oral history and the SAT’s archival materials, we construct an “animal biography” of Wei Wei that illuminates his individuality and the interwoven lives of panda and handler.17 Furthermore, we drew on primary sources such as Japanese-language newspaper and magazine articles, municipal government publications, a 1981 SAT brochure, and an issue of the Japan–China Friendship Association (JCFA) newsletter to explore the panda performer’s impact on Japanese audiences and their perceptions of pandas. This contextualization highlights the political significance of municipal-level cultural diplomacy involving the JCFA — an aspect not emphasized in earlier research, such as Ienaga’s comprehensive study of panda diplomacy.18 Finally, we located archival newsreels and films featuring giant pandas from the Internet, VHS, and DVD sources. These visual materials help contextualize the interview data; in particular, animated films reveal representations of imaginary pandas prior to Wei Wei’s arrival and demonstrate his influence on Japanese popular culture. Drawing on multilingual materials and diverse qualitative methods, this article offers a unique interdisciplinary, trans-Asia approach to questions of animal agency, emotional labour, international relations, media, and performance.

The first section below explains the historical and scholarly significance of studying panda circuses. The second section charts the emergence of China’s panda circus under the environmental and cultural policies of the 1970s and 1980s. Through a biography of Wei Wei, we describe the political and cultural forces that enabled him to become an animal celebrity, while also showing how the intertwined lives of Wei Wei and Lu were shaped by a historical era in which both the giant panda and a generation of Chinese youth experienced gradual political and cultural shifts. The third section widens the policy analysis to international relations, examining the municipal-level “friendship-city diplomacy” led by Japanese local governments. These municipal engagements made a touring panda circus possible, expanding opportunities for human–animal encounters and enabling Wei Wei and his human co-performers to reach a wider audience than zoo pandas could. This section also analyses how media images of the circus panda evolved from the 1970s to the 1980s, preparing Japanese audiences for the live performances. Finally, we address Wei Wei’s “biting incident” on 9 January 1981: on the morning after the opening night, Wei Wei attacked both his handler and keeper, forcing the local organizer to cancel a public exhibition. By analysing this episode from the perspectives of Wei Wei’s handler and Japanese media, we consider the extent to which Wei Wei resisted his imposed role as a “zoo panda” and what this moment of “panda rebellion” meant for the human and animal participants in this chapter of China–Japan exchange.

The Giant Panda as Political Subject, Emotional Labourer, and Imaginary Friend

Live animals have circulated as state gifts to facilitate international relations since the thirteenth century.19 Some were domesticated animals, such as horses, valued by humans for food or transport. Others were rare wild animals — including giraffes, platypuses, and elephants — whose rarity and beauty were expected to evoke positive feelings in the recipient.20 Offering a rare animal such as the giant panda could also affirm a geopolitical hierarchy or restore friendly relations.21 This section outlines the historical and scholarly contexts for studying a unique form of animal diplomacy — panda circuses — while highlighting our interventions.

Between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the giant panda attracted the attention of Euro-American animal traders, zoologists, naturalists, and elites who hunted wildlife in colonized regions to advance colonial knowledge institutions such as natural history museums and zoological gardens.22 It was not until 1941 that the giant panda became directly associated with the Chinese nation. That year, the first pair of giant pandas was given to New York’s Bronx Zoo to support a U.S.-based fundraising campaign for China’s resistance against Japanese aggression. Soong Mei Ling, then First Lady of the Republic of China, described the two “gift pandas” as “a very small way of saying ‘thank you’” to American donors.23 After 1949, the PRC continued to use the giant panda as a diplomatic tool. Beijing sent giant pandas to the USSR in 1957 and to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in 1965. Shortly before Kang Kang and Lan Lan’s journey to Japan, the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., welcomed Ling Ling and Hsing Hsing, who were widely regarded as a “high-profile symbol of the rapprochement” between the United States and the PRC.24 These events drew the attention of journalists and policy analysts, who debated the effectiveness of Beijing’s panda diplomacy.25 In the China–Japan context, Ienaga’s study delineates the vast array of human actors — from political figures, media creators, and celebrities to zoo directors — who helped secure the giant panda’s superstar status in animal diplomacy and enabled the PRC to navigate complex international relations.26 Yet these discussions overlook the agency of nonhuman animals and the intricacies of human–animal interactions in the history of international relations.

Over the past decade, some social science researchers have challenged anthropocentric assumptions about nonhuman animals in contemporary politics. They argue that nonhuman animals are more than political instruments or symbolic pawns: they can act as political agents in their own right, and human–animal relations are always reciprocal.27 To restore animals to political history, Mieke Roscher has proposed an interdisciplinary approach that takes representations of animals seriously while also analysing the material lives of specific animals in historical context.28 In conversation with this literature, this article explores both the material and symbolic dimensions of the panda circus. We examine how a Chinese nationalist discourse of “the giant panda” shaped Wei Wei’s subject position and his relationship with Lu. By positioning Wei Wei as a collaborator in the human–animal encounters that shaped the development and exhibition of the panda circus, we emphasize his “assembled agency,” or the effects of his will embedded within heterogeneous assemblages of people, nonhuman animals, institutions, and environments.29

Moreover, the giant panda not only performed a sociopolitical role but also contributed to the expansion of a Chinese–Japanese transnational cultural economy. As an animal labourer in a circus, Wei Wei embodied and reproduced “nonhuman charisma”—a particular combination of appearance and behaviour that attracts audiences. Different species can display varying degrees of appealing or feral charisma, eliciting positive and/or negative affects in the humans who encounter them.30 Since the World Wildlife Fund (WWF; now the World Wide Fund for Nature) chose the giant panda as its logo in 1961, the panda’s perceived “cuddly charisma” has been further consolidated through global wildlife conservation campaigns.31 This article shows that Wei Wei’s aesthetic and corporeal charisma in performance was cultivated through intensive human and animal labour, especially emotional labour. Existing scholarship on emotional labour largely focuses on human actors’ conscious or unconscious management of emotional expression in the production of service commodities — for instance, the work of sales assistants and flight attendants.32 However, Andrew McEwen’s study of Canadian soldiers’ emotional attachment to their horses during the First World War and Kendra Coulter’s discussion of multispecies care work (e.g., animal-assisted therapy) demonstrate the significance of emotional labour performed by trained nonhuman animals in prescribed roles.33 Drawing on these insights, this article uses emotional labour as a critical lens to analyse the interspecies collaboration between Lu and Wei Wei and to discuss the successes and failures of the SAT panda circus tour in Japan. Our findings also aim to disrupt the dominant cultural frame that celebrates the giant panda’s “cuddly” qualities while obscuring the intensive labour performed by both handler and panda in staging a public performance. In doing so, this article contributes to an emerging literature that centres animal labourers’ responses to human demands and exploitation in the wider capitalist economy.34

Finally, even before Wei Wei became a media sensation, the figure of the circus panda was already popular in Japan. Within this discursive context, we analyse representations of circus pandas in general and of Wei Wei in particular. Our analytical framework draws on critical media and animal studies scholarship, which highlights the role of media and communication in building public consensus and producing systems of value and knowledge that marginalize nonhuman animals.35 Matthew Cole and Kate Stewart’s study of media representations of “cute animals” and childhood is especially relevant.36 They demonstrate that family practices and mass media reproduce dominant representations of human–animal relations, legitimating or concealing human exploitation of nonhuman animals.37 Building on this work, we examine the forms of human–animal relations projected by imaginary circus pandas in Japanese media culture before Wei Wei’s arrival. We argue that Wei Wei’s live performances created a rare opportunity for Japanese audiences: they were able to witness interactions between a giant panda and his human collaborators and to glimpse the discipline and hard work behind the panda entertainer’s role. We show that Wei Wei’s biting incident animated a new emotional landscape, articulated through Japanese media discourses on what humans can and cannot do to giant pandas and other animals. Together, these cultural productions heightened Japanese public awareness of animal suffering and invited audiences to join a transnational wildlife conservation movement.

The Invention of the Panda Circus in the PRC, 1960s–1980s: The Discovery of Wei Wei

Wei Wei was captured in the Wanglang National Nature Reserve (hereafter Wanglang), China’s first nature reserve, located in northern Sichuan Province (approximately two thousand kilometres west of Shanghai). His journey from Wanglang to Shanghai was shaped by two parallel policy processes: (1) the regulation of natural resources and (2) the suppression and subsequent revival of state-run arts and cultural institutions. Both formed part of the nation-building efforts of the early decades of the PRC, when the new government sought to establish its rule and legitimacy through various modernization policies. In this political context, socialist nationalism became a driving force behind the PRC’s new ecological policies and the protection of native animals, including the giant panda. At the same time, the giant panda was incorporated into a system of natural symbolism central to forging a shared national identity.38

In 1959, the PRC government included the giant panda in the first list of nine so-called “rare and precious species” and prohibited private hunting, trapping, and the export of giant pandas. Three years later, the Ministry of Forestry expanded this list to nineteen animals, again placing the giant panda at the top of the protected “rare and precious species”.39 Subsequently, Wanglang was designated the country’s first national nature reserve as a protection area for giant pandas. The giant panda thus became the flagship species of Wanglang’s conservation programme.40

In parallel, the PRC government began developing cultural products to promote China’s international reputation. In 1973, the Shanghai Science and Education Film Studio (上海科学教育电影制片厂) was tasked with producing China’s first full-length, colour science documentary, entitled Panda.41 According to filmmakers’ memoirs, however, the elusive nature of the giant panda posed a major challenge. After several months of searching in the cold mountains of Wanglang, the crew had encountered only one panda. In desperation, the director and producer decided to “recruit” a wild panda cub for the project. With assistance from local forestry officials, the team located and “kidnapped” a male cub from his mother.42 The director named the cub “Wei Wei”, and the government dispatched Zhang Tie Shan (张铁山), a bear trainer from the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe (SAT), to join the film crew in Wanglang. Wei Wei was only a few months old at the time. Under Zhang’s training, he learned to follow cues, climb up and down trees in front of the camera, and “perform” for a human audience during filming.43

Wei Wei’s eventual entry into live entertainment was also tied to a cultural revival at the SAT in the early 1970s. Animal circuses had a long history in China but received little state attention until the late 1950s, when a Soviet animal circus impressed Chinese audiences.44 In response, several state-run acrobatic troupes, including the SAT, launched animal circus programmes. Wei Wei’s first handler, Zhang Tie Shan, was among the early members of the SAT circus team, which trained horses, tigers, bears, monkeys, and dogs. In 1966, however, the SAT disbanded its animal circus programme and transferred the animals to a local zoo, as animal circus acts were deemed inappropriate for socialist culture.45

Songster’s research on China’s panda craze during the 1960s shows that, unlike many animals, the giant panda was not symbolically associated with either the exploitative aspects of earlier Chinese dynasties or the humiliation of China’s defeats by European and Japanese imperial powers. Instead, giant panda imagery was viewed as a “safe” material for nationalist cultural production.46 Artists and artisans widely adopted the giant panda as a source of inspiration, and many Chinese manufacturers incorporated the panda into branding and marketing.47 Overall, this period solidified the association between the giant panda and socialist nationalism.48 In Chinese media, the giant panda is even referred to as guobao (“national treasure,” 国宝).49 Amidst the panda’s rising cultural prominence, SAT leadership decided to adopt Wei Wei and train him as a circus performer. After the documentary was completed in Wanglang, Wei Wei was transferred to the SAT at the end of 1974.

According to Wang Feng (王峰), former vice-director of the SAT, a new cultural policy adopted after the PRC joined the United Nations in 1971 inspired the idea of training a giant panda.50 This policy identified acrobatics as one of the few cultural forms capable of promoting “Chinese culture” internationally.51 Thus, the growing political importance of circus entertainment, combined with the giant panda’s status as a national symbol, provided justification for reviving the animal circus programme. The SAT recruited Wei Wei’s second and primary handler, Lu Xing Qi (陆星奇), along with a group of young people, to pursue this goal.

Lu Xing Qi was among the several million urban youths sent to rural areas under the state’s “send-down” policy.52 He worked at the Huangshan Tea Farm in Anhui Province and had no prior experience with animal care. “Our farm had over eight thousand people,” Lu recalled. “I was lucky to be selected and join the acrobatic troupe.” He described the recruitment as a miracle because it allowed him to return to Shanghai and earn a good government salary, while most of his co-workers remained in the countryside for years before reuniting with their families. Lu first learned to train black bears under his mentor Zhang Tie Shan. When Wei Wei arrived, Lu was assigned to care for and train the young giant panda. The revival of the animal circus brought Lu social and economic mobility, whereas Wei Wei was compelled to leave Wanglang and begin life as a circus animal in a closely monitored enclosure.

Bonding with an Emotional Panda

The literature on animal–keeper and animal–trainer relations suggests that handlers’ perceptions of their work and their relationships with nonhuman animals are influenced by their own life histories, by prevailing political–cultural notions of the “self”, and by broader political–economic conditions.53 Belonging to the “send-down” generation, Lu Xing Qi emphasized that becoming an animal handler was not his personal choice; rather, he was fortunate to have been “chosen” by the SAT. Lu’s narratives regarding his devotion to creating the giant panda circus must therefore be understood as expressions of his evolving subjectivity and his allegiance to the state-run SAT under socialism. Although Lu could suppress personal desires and interests to comply with government directives, his story clearly reveals his struggle with Wei Wei’s individuality and how he used emotional labour to train and perform with this “national treasure”.54

Lu Xing Qi trained black bears, lions, tigers, horses, and elephants. In retrospect, he recalled that training Wei Wei was his most difficult challenge. “If you were never hurt [by Wei Wei], you would think he appeared to be a lovely animal,” he said. “I knew he could be very unpleasant because I was hurt by him. He could be scary and stubborn.” On the one hand, Lu acknowledged Wei Wei’s cute appearance, which often triggered human spectators’ affection. On the other hand, he described his close observations of and efforts to manage the giant panda’s more ferocious behaviours, which appeared throughout their long-term interactions.

[Pandas] can get upset suddenly. When Wei Wei was nervous or scared, his ability to follow rules and orders diminished. Over a long time, [I] built a relationship with him. Usually everything went well between us. [But] when he was shocked or angered, [I] could lose control over him completely. He could make a huge mess, and bite things and people around him. During training, if [Wei Wei] did not want to follow your order, he would not eat the treats you fed him. It was hard to figure out Wei Wei’s character.

A growing body of literature has shown that many nonhuman animals have rich, complex emotional lives.55 They can experience fear, joy, grief, love, and forms of embarrassment.56 For animal keepers and handlers, recognizing and interpreting animal emotions helps predict future behaviour and facilitates the development of effective training and performance strategies that attend to the animals’ emotional states.57 Lu’s descriptions of Wei Wei’s character indicate how well he came to know the panda’s “cuddly and feral” charisma.58 He explained:

The expression in Wei Wei’s eyes and the movements of his ears changed from time to time. If you know him well, you could tell what mood he was in by looking at his face. He had joy, sorrow, and rage. When he was nervous, his round eyes would open wide. His ears would point upward. When he was not pleased, he would pace back and forth and swing his body. Sometimes he would drop his head if he was unhappy.

Lu stressed the importance of spending extensive time building a close relationship with Wei Wei. He recalled that he “took him out for a walk, sat with him, and caressed him.” Bonding with Wei Wei also involved disciplinary techniques: one was to leave the overstimulated panda alone until he calmed down; the other was to withhold food. According to Lu, however, the second method was rarely used because of Wei Wei’s temperament and his status as a “national treasure”.

Throughout the interview, Lu anthropomorphized Wei Wei — using human terms to describe the panda’s emotions or feelings. Anthropomorphism can make animals’ behaviours and emotions more intelligible to human listeners.59 This is not to say that Wei Wei experienced happiness or sadness in the same way humans (or even other species) do. Rather, Lu used human-language analogies, such as “sad” or “happy,” to express what he believed Wei Wei might have felt. His recollections of Wei Wei’s upbringing at the SAT provide a unique window into how the panda’s subjectivity evolved in this socio-cultural milieu. Lu’s account suggests that Wei Wei gradually formed an intimate relationship with him and bonded with other animal performers at the SAT. Such affective ties among humans and nonhuman animals laid the foundations for Wei Wei’s development as a performer.

Creating a Panda Circus

Animal circuses enchant audiences by staging spectacles that defy expectations of what animals — or humans — can normally do.60 Wild animals such as giant pandas are not expected to follow human commands. Thus, the staging of a panda performance challenges conventional ideas about wildlife and stimulates fantasies of panda–human relationships. Lu understood the panda circus as an innovation that built upon existing bear-training techniques. “If the giant panda were trained to perform difficult tricks [like those in the bear acts]”, he observed, “[this] might generate the feeling that [the trainers] did not respect the panda and forced him [to work]”.

Archival video footage of Wei Wei’s performance at the 1983 Chinese Spring Festival Gala offers clues to the cultural messages the acts conveyed to public audiences.61 The performance consisted of seven segments: (1) walking with a stroller; (2) riding a toy horse; (3) rolling forward; (4) juggling a ball with all four paws; (5) eating snacks; (6) playing on a slide; and (7) playing a trumpet while seated in a carriage pulled by two dogs. The emotional power of such animal acting is often achieved by embedding trained behaviours within a narrative structure.62 According to Lu, each of Wei Wei’s movements was intended to imitate a playful child. The choreography invited spectators to believe that the giant panda was having fun onstage and that he had not undergone harsh or exhausting training. This seemingly effortless, spontaneous human–animal performance amplified Wei Wei’s “cuddly charisma” as well as his status as China’s national treasure.

Lu acknowledged that Wei Wei’s success was the product of lengthy training and experimentation. For example, riding a toy horse required Wei Wei to maintain sufficient balance not to fall from the prop. To achieve this, Lu gradually adjusted the rocking motion so the panda would learn to sit steadily. To make Wei Wei resemble a human child in the slide act, Lu trained him to sit on his bottom with his head lifted while sliding down. Similarly, incorporating dogs into the act required careful planning and patience. Initially, Wei Wei attacked his canine co-performers. To solve the problem, Lu placed their cages close together so the animals could gradually acclimate. Ultimately, this human–animal co-performance relied on Lu’s understanding of Wei Wei’s personality and abilities, the emotional exchanges between humans and nonhuman animals, and the suppression of sensory differences between human and animal bodies.63

For instance, in their natural habitat, giant pandas rely on smell to identify mating partners and mark territories.64 At the SAT, however, the importance of olfactory communication was not immediately appreciated. Lu found that Wei Wei occasionally failed to follow directions during performances. Because every segment was precisely timed, these moments—such as when Wei Wei would continue rolling on the floor—could disrupt the entire show. Eventually, Lu and his colleagues discovered that Wei Wei’s “disobedience” was triggered by the perfume worn by foreign audience members. “Wei Wei was very sensitive to this smell,” Lu recalled. “When he sensed fragrant chemicals, his nervous system was stimulated. He became excited and vocal.” Lu responded by spreading perfume around Wei Wei’s enclosure daily. After several months, the panda learned—or was conditioned—to suppress his excitement in response to this sensory stimulus and ceased acting out onstage.

In short, creating the giant panda’s stage persona required physical and emotional labour from both Lu and Wei Wei. Moreover, Wei Wei’s olfactory training illustrates how his working environment changed. In the early SAT years, Wei Wei was treated as an animal artist–worker contributing to the revival of the animal circus programme. His primary task was to gain the approval of party officials and to entertain domestic audiences, who were unlikely to wear perfume. In the early 1980s, however, China’s neoliberal reforms aimed to attract foreign investment, and welcoming international tourists became part of these policies. Wei Wei’s encounters with foreign audiences in fragrant performance spaces therefore reflected this major shift in China’s political–economic priorities.

In 1980, the central government finally gave the panda circus permission to join the SAT’s Japan tour. Unlike previous diplomatic missions, the troupe’s leadership hoped that this visit would also generate economic revenue. Including Wei Wei in the programme would ensure both political and financial benefits for the SAT and the Chinese government. The following section examines the “friendship-city diplomacy” under which Wei Wei was brought to Japan and analyses Japanese media discourses surrounding the circus panda before and during the SAT Japan tour. As shown, this unique cultural export created both opportunities and challenges for the giant panda and his human collaborators.

Panda Entertainer Came to Japan

Beyond the initial performances in the four major cities — Osaka, Yokohama, Nagoya, and Tokyo — the troupe visited ten additional locations far from industrialized urban centres, including the northernmost prefecture of Hokkaido and the southernmost prefecture of Okinawa.65 Unlike Kang Kang and Lan Lan, Wei Wei’s performances required careful logistical and business coordination between the SAT and various local Japanese stakeholders, including government offices, non-governmental organizations, and private companies. Japanese media reporting on Wei Wei and the SAT tour drew attention from both national and local outlets. Their narratives evoked public memories of imaginary giant pandas from earlier animated films and television shows; this dispersed form of cultural production heightened Wei Wei’s celebrity status across Japan and increased the economic and cultural value of the panda circus.

The Friendship City Diplomacy: Yokohama, Osaka, and Shanghai

The SAT’s decision to include Osaka and Yokohama as the first two stops of the 1981 Japan tour was not arbitrary. Historically, both cities had cultivated close ties with Shanghai through multiple waves of trade, migration, and foreign investment. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Yokohama hosted Japan’s largest Chinese community.66 After the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), Japan’s expansive economic policies, combined with military aggression and the colonization of neighbouring regions, channelled substantial Japanese capital into China until Japan’s surrender in the Asia–Pacific War (1937–45). Many Japanese companies — including manufacturers originally based in Osaka — established offshore factories in Shanghai,67 where a sizeable Japanese civilian community subsequently flourished.68 Yokohama, for its part, became “a symbolic exemplar of Sino-Japanese relations”.69

However, postwar U.S. hegemony interrupted state-level relations between China and Japan. The San Francisco Peace Treaty and the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty constrained the Japanese government’s ability to engage independently with the PRC. In response, Japanese intellectuals and businesspeople with pre-existing ties to China began promoting a Japan–China friendship movement from the late 1940s onward.70 This movement included the Japan–China Friendship Association (JCFA), founded in 1950. By the late 1950s, numerous China-related NGOs and research institutes had emerged and collaborated with the JCFA to expand the friendship movement.71 Alongside the Promotion of Japan–China Trade (APJCT), the JCFA became one of the seven key organizations that established informal communication channels between Japan and the PRC prior to the normalization of diplomatic relations.72

Osaka and Yokohama were among the first Japanese cities to pursue a so-called “friendship city” diplomacy shortly after the signing of the Japan–China Joint Communiqué in 1972. “Friendship city” (or sister-city) diplomacy originated in Europe and the United States, where municipal governments sought to rebuild relations with former adversaries after the Second World War.73 In 1973, the visit of the China–Japan Friendship Association (from the PRC) to Japan’s thirty-eight prefectures “laid a precious seed” for developing friendship city agreements between the two countries.74 The Yokohama–Shanghai friendship agreement was signed later in 1973, followed by the Osaka–Shanghai agreement in 1974.75 These agreements encouraged business communities to establish partnerships with Chinese counterparts and facilitated the creation of local JCFA branches at the prefectural level. Moreover, Japan’s regional governments were eager to cultivate opportunities for developing local industries.76

In August 1978, Japan and China signed the Treaty of Peace and Friendship, laying the groundwork for long-term bilateral relations beyond U.S. and Soviet influence. Soon afterwards, on 6 December 1979, the two governments signed the China–Japan Cultural Exchange Agreement during former Prime Minister Ohira Masayoshi’s (大平正芳) visit to Beijing. This agreement provided a policy framework for expanding exchange activities between China and Japan in the fields of arts, culture, education, scientific research, and sports.77 The SAT’s 1981 Japan tour emerged within this new phase of China–Japan relations.

Invited by the JCFA in 1974, the SAT’s first mission in Japan sought to promote the normalization of bilateral relations. By 1981, however, the SAT tour received much broader support from Japanese municipal governments and NGOs. Yokohama mayor Saigo Michikazu (細郷道一) described the “1981 Yokohama SAT shows accompanying a panda” as the third major public event celebrating the Shanghai–Yokohama friendship agreement, following the Yokohama Japan Industrial Exhibition in Shanghai (1979) and the Shanghai China Craftwork Exhibition in Yokohama (1980).78 Tokuichi Hayashi (林得一), founder of Nitchu Geikyo (Japan–China Art Association, or JCAA), initiated negotiations with China to secure permission to bring the national treasure Wei Wei to Japan.79 Additionally, Nagano Shigeo (永野重雄), President of the Japanese Chamber of Commerce, met with Liu Xi Wen (刘希文), Assistant Administrator of International Trade of China, to request that the SAT bring the circus panda “to entertain children in Japan”.80 Thus, Beijing’s decision to allow Wei Wei to travel was, in fact, a response to requests from Japanese NGOs and business leaders. On the one hand, the 1981 mission signalled the Chinese government’s increasingly relaxed attitude toward economic–cultural exchanges. On the other, the involvement of the Japanese business community reflected the so-called “China Boom” of the late 1970s, when Japanese companies sought to expand trade and export manufacturing plants to China.81

These city-level diplomatic initiatives also opened space for Japanese NGOs to collaborate with their Chinese counterparts. The JCFA and JCAA were the principal organizers of the tour, and JCFA-affiliated organizations played active roles in promoting the SAT and Wei Wei. For example, the JCFA’s January 1981 newsletter, circulated among local groups nationwide, included detailed descriptions and an itinerary of the SAT tour.82 The Japan–China Association for Cultural Exchange co-sponsored the events along with Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Culture, and the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China.83

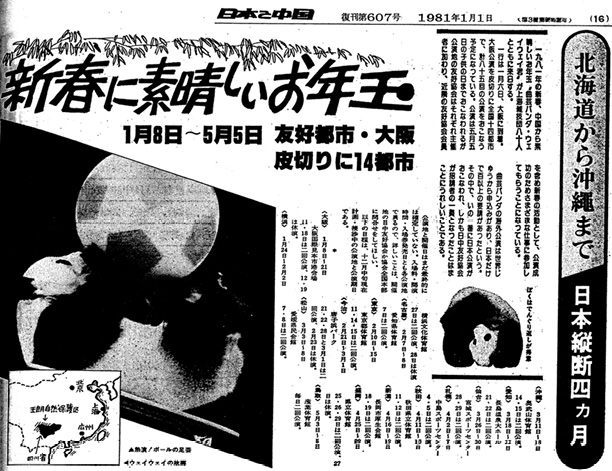

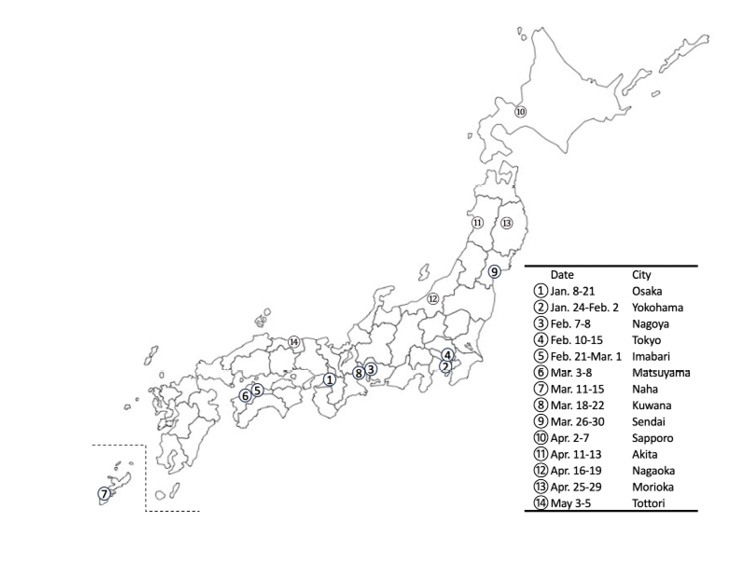

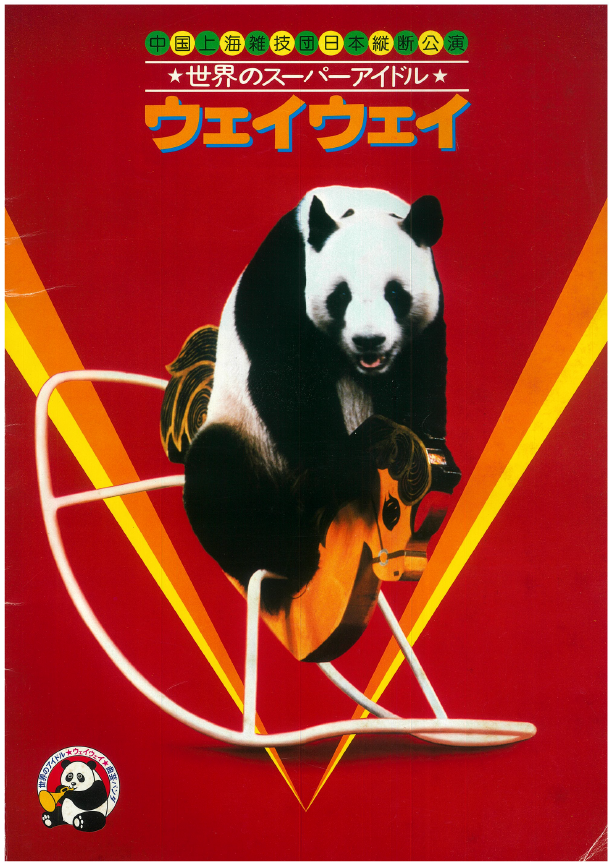

The SAT itinerary shows that the troupe typically gave two shows per day, with the number of performances ranging from six to fourteen in each locale; they usually stayed for three days to a week (Figures 1, 2).84 Ticket prices varied by venue but remained affordable for middle-class families.85 Overall, the SAT tour brought Wei Wei “to the doors of the Japanese masses”86 and allowed audiences — many of whom might not have had the opportunity to visit Ueno Zoo — to experience directly the physical presence and charisma of a giant panda (Figure 3). Furthermore, as the next section demonstrates, the touring circus and accompanying exhibitions quickly became sites where the Japanese public grappled with consumerist culture, negotiated the meanings of human–animal relations, and translated their viewing experiences into personal understandings of Japan–China relations.87

Fig. 1 SAT tour itinerary published in Nihon to Chūgoku (Japan and China), 1 January 1981, 16. The article’s main title reads: “A Wonderful New Year’s Gift”, and the subtitles read: “From Hokkaidō to Okinawa, a four-month tour across Japan”, and “From 8 January to 5 May: fourteen cities, beginning with the friendship city Osaka”.

Fig. 2 A visualization of the 1981 SAT Japan tour itinerary based on the itinerary in the Figure 1.

Circus Pandas in Japanese Film and Media:

From an Imaginary Friend to an Unruly Entertainer

Before Wei Wei became a media sensation, the figure of the imaginary panda performer was already popular in Japan. Shortly after the arrival of Kang Kang and Lan Lan, major Japanese studios released three animated films featuring giant panda characters. These works reflected a broader trend in children’s animated television programming in which animal protagonists were especially popular. The first short film, Panda! Go, Panda! (Panda kopanda), was released by Tokyo Movie and distributed by Toho on 17 December 1972.88 It marked the earliest collaboration between Miyazaki Hayao (宮崎駿, scriptwriter, production designer, layout) and Takahata Isao (高畑勲, director), who would later become leading creators at Studio Ghibli.

In Panda! Go, Panda!, a young girl, Mimiko, meets a male panda cub, Ponchan, and his father, Papanda, who have escaped from a zoo. The father–son pair demonstrate their ability to imitate human movements and occasionally display superhuman capabilities. Papanda learns to perform handstands and skip rope with Mimiko, and as the story develops, Mimiko becomes a mother/wife figure to the panda duo, forming an interspecies, family-like unit. By the film’s end, Papanda dons a business suit, commutes by train to work at a zoo, and performs circus tricks for visitors — suggesting his assimilation into human urban life. The sequel, Panda! Go Panda! — The Rainy Day in Circus (Toho, 1973), follows Ponchan as he accidentally enters a circus tent and ends up balancing on a rolling ball. He and Mimiko become acquainted with other circus animals. After a flood traps the circus troupe, Mimiko, Ponchan, and Papanda rescue the animals. In the finale, Papanda uses a heroic superpower to stop a runaway train carrying the circus animals and poses triumphantly atop an acrobatic pyramid formed by the troupe.

Fig. 3 Cover of the 1981 SAT Japan tour brochure. The main title reads: “China’s Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe Touring Japan — The World’s Super Idol, Wei Wei”.

Meanwhile, Toho’s rival company Toei released a feature-length film, Panda’s Great Adventure (1973), a coming-of-age story about a young panda prince, Lon Lon, from the Bear Kingdom. After failing to complete a mission assigned by the Queen Mother, Lon Lon and his friend Pinch are captured by a circus troupe. Unlike the previous two shorts, this film foregrounds human–animal conflict: when Lon Lon refuses to learn a trick, an exasperated human trainer beats him with a whip. At the circus, a female panda trapeze artist, Fifi, befriends Lon Lon and Pinch and introduces them to a tiger, an elephant, and a monkey, each with distinct personalities. Encouraged by Fifi to become a circus star, Lon Lon trains hard to master acrobatics. Nonetheless, he eventually escapes — thanks to an accidental fire — and returns to the Bear Kingdom with Pinch to prove his courage and perseverance.

Across these three films, panda protagonists are portrayed as individuals with rich emotional lives. Their acrobatic abilities are imbued with meanings such as intelligence, bravery, and dedication. The circus becomes a site of human–animal encounter where the panda characters can demonstrate agency. Thus, before Wei Wei’s arrival, Japanese audiences were already familiar with the idea of a panda performing in a circus, even though this imagery was not directly linked to the PRC. When JCAA founder Hayashi Tokuichi first saw Wei Wei perform at an SAT show at the Canton Fair, he recalled that he “felt as if [he] was in a fantasy land”—an experience that inspired him to bring Wei Wei to Japan.89

We found that characteristics of cinematic circus pandas resurfaced in early media portrayals of Wei Wei. For example, on 1 January 1981, shortly before the SAT tour began, Heibon Weekly published an article by television personality and actress Suehiro Makiko (末広真季子), who reported from Shanghai on Wei Wei and the forthcoming tour.90 A special photo spread emphasized the bond between handler and giant panda: “Mr. Lu devotes his love to Wei Wei as if [he were] his own child.” “As if they could communicate in a language, Mr. Lu and [Wei Wei] can relate to each other through their hearts.” Such depictions reproduced a romanticized narrative of family-like care and emotional intimacy between humans and a giant panda. What was new for Japanese audiences, however, was “Mr. Lu”, whose presence reminded them of Wei Wei’s connection to the PRC and invited them to participate in this form of animal diplomacy. These media images also functioned as advertisements, enhancing the economic value of the giant panda as an entertainer capable of performing rare tricks to satisfy human fascination with cuteness.91 A recurring metaphor compared Wei Wei to children’s “New Year’s gift money”,92 highlighting a consumerist view of the giant panda as a special cultural commodity for children — distinct from the “national treasure” imagery in China.93

Yet Wei Wei was not simply an object of consumption destined to reproduce cuteness. On the second day of the SAT’s visit to Japan, Wei Wei attacked his handler and keeper during a daytime exhibition. Lu Xing Qi’s edited recollection of the incident provides insight into how Wei Wei acted in this context:

Wei Wei saw many people and excitedly ran around in the exhibition room. Then, he bit a keeper. I went to his room to give him some instructions because he disobeyed the rules. So, I stood close to him, holding my baton and scolding him. Suddenly, he snapped my shoe. Then he tried hard to pull me toward him. Wei Wei’s teeth bit into my fourth toe. My colleagues came to help and pulled me away from Wei Wei. Everyone was scared after this happened. So I had to endure the pain to shepherd him into the cage. When he was finally in the cage, he was still holding my shoe in his mouth.

After I came back from the hospital, I went to see Wei Wei. He dropped his head and ignored me. I told my troupe leader that we should still perform. If we gave up tonight, the impact could be huge. This was the first time that China brought an animal act overseas.

On the stage, I was very nervous, even though I was smiling at the audience. I had a wounded foot and pretended that nothing had happened. It was not until the performance ended and I brought Wei Wei to his cage that I finally could relax.

Lu’s memory of the biting incident exposes several layers of tension. First, Wei Wei had never been portrayed as an aggressive wild animal; his violent behaviour disrupted the Japanese public’s imagination of the giant panda as a “happy child”. Lu’s inability to tame Wei Wei also shattered the illusion of a predictable human–panda relationship: the handler who supposedly understood the panda’s moods and temperament could not control him in the exhibition space. Second, Wei Wei’s refusal to cooperate and Lu’s subsequent decision to continue the performance revealed the tension between Wei Wei’s individuality and Lu’s commitment to fulfilling his government mission—an element absent from earlier publicity. Lu cast himself as a brave, hardworking state employee who cared deeply about China’s international reputation and the SAT’s future economic prospects. This sense of duty compelled him to transform himself from a loving caretaker into a circus hero who took risks, endured physical pain, and used significant emotional labour to perform with Wei Wei onstage.

Like escaped zoo animals, Wei Wei’s biting incident demonstrated his “assembled agency”, embedded in networks of journalists, media outlets, organizers, audiences, and exhibition and performance spaces.94 Wei Wei’s rejection of the role of a zoo panda exposed a fundamental truth about animal exhibition and circus performance: humans can never fully subject animals to their power. Various media discourses quickly emerged to challenge the widely circulated image of the giant panda as a docile creature. The unexpected panda–human struggle reanimated public emotions and generated an interest in understanding the origins of Wei Wei’s violent reaction.95 Reporting nationwide, the Asahi Shinbun evening edition of 9 January 1981 ran the headline “Panda Wei Wei’s ‘Rebellion’”. Rather than focusing solely on human projections of the panda’s emotions, the article sought to interpret Wei Wei’s negative feelings and aggression toward trainers who had been presented as parental figures.

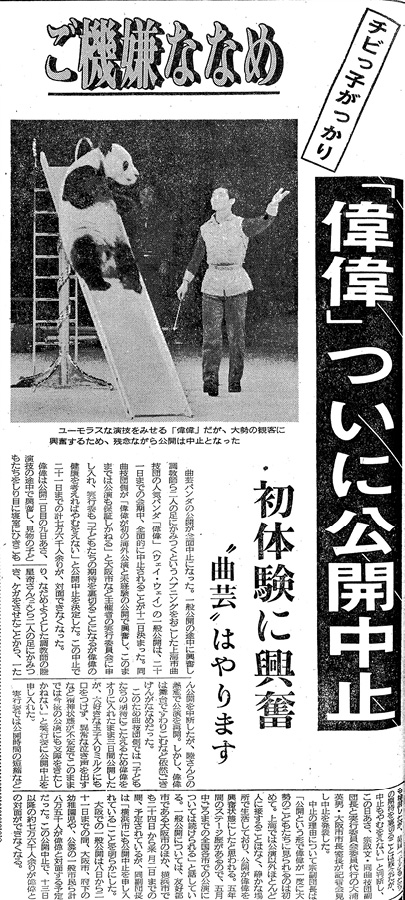

A local Osaka Shinbun article reported that 3,400 kindergarteners witnessed Wei Wei’s “strike”, and more than 5,000 children subsequently missed their free viewing opportunity. To “appease children’s expectations”, organizers resumed public viewing the next day, displaying a caged Wei Wei, but noted that “he did not touch his favourite milk mixed with egg and wailed unusually, showing his emotional instability”, leading to the cancellation of the entire viewing programme in Osaka. Organizers explained that “Wei Wei normally lived in a quiet place” and that “this is the first time he was being watched by so many children at once”,96 but remained confident that, given his five years of stage experience, the tour could continue. Indeed, Wei Wei performed with the SAT that same evening as scheduled. Nonetheless, public viewing in Yokohama, the next tour stop, was also cancelled.

When the news framed the biting incident as a “rebellion” or “strike”, it drew attention to Wei Wei’s emotional and physical needs, which had not previously been part of the giant panda’s public image. Although the term “strike” was used jokingly, it highlighted Wei Wei’s status as an entertainment worker resisting his treatment and the demands placed upon him as a “zoo panda”. We argue that Wei Wei’s assembled agency had two major effects. First, his unruly behaviour disrupted human political expectations and economic arrangements during this episode of China–Japan diplomacy. Second, within the Japanese discursive context, Wei Wei’s ferocity activated a new mode of anthropomorphizing the giant panda. Journalists represented his behaviour by comparing the panda’s experience to human challenges in working life — changes in living or working environments, overwork, and emotional strain. These media discourses encouraged the Japanese public to recognize Wei Wei’s suffering and opened space for considering one’s ethical responsibility toward another’s wellbeing.97

Concluding Remarks

This article has examined the invention and exhibitions of the giant panda circus to explore the power of giant pandas in international relations and in the Chinese–Japanese transnational cultural economy. Politically, Chinese and Japanese stakeholders used the SAT’s 1981 tour to celebrate the friendship-city agreements between Shanghai and major Japanese cities such as Osaka and Yokohama. Wei Wei’s popularity demonstrated the success of the SAT’s mission to promote a friendly image of post-Mao China to the Japanese public. While Wei Wei embodied the Chinese nation, Lu Xing Qi aimed to represent a new generation of model Chinese citizens. Moreover, the far-reaching impact of the tour highlights the effectiveness of a decentralized form of diplomacy—one that renewed historical linkages between Japan and China, built on the achievements of earlier friendship movements, and mobilized municipal governments, local business networks, and non-governmental organizations. As a result of these local diplomatic practices, Wei Wei and his human co-performers could travel across Japan and win the hearts of tens of thousands.

Economically, Wei Wei’s star aura helped the SAT generate substantial profits. Promotional articles in Japanese print media frequently used phrases such as “the first and the last” and “the first time in the world,” stressing the uniqueness of the panda circus and the value of witnessing this spectacle. Five years later, Wei Wei was invited back to Japan and performed in 150 shows over a five-month period.98 Japan’s popular magazines — including the women’s magazine Josei Sebun (Women Seven), and the entertainment magazine Myojo — ran detailed reports on the troupe’s second visit and published numerous photographs of Wei Wei.99 Even after his retirement, the popularity of the panda circus continued in Japan. The SAT’s second panda, Jiao Jiao (known as Chao Chao in Japanese), performed in twenty-one Japanese cities in 1989.100 The revenue from these commercial tours not only enabled the SAT to renovate its training and exhibition facilities but also allowed individual performers to receive bonus salaries and special recognition.101 For example, Lu Xing Qi was awarded numerous prizes, including titles such as Shanghai Model Worker and First Rank Performer.102 It is also reasonable to infer — based on the economic outcomes of comparable public events — that these tours brought profits to local performance venues, nearby retail businesses, transportation companies, and the wide range of firms involved in event promotion and logistics.103

However, as we have shown, the gains enjoyed by humans came at ecological and emotional cost. Wei Wei was removed from his birthplace to become a circus performer. The panda circus’s aesthetic strategy concealed the labour-intensive training regime and the emotional labour performed by both the giant pandas and their human co-performers. Even so, the panda circus created an unprecedented form of engagement with audiences. The immediacy of human–animal contact allowed Japanese spectators to glimpse the giant panda’s agency and complex emotional world. While his autonomous will was often represented as inseparable from his charismatic animal-star persona, Wei Wei’s “rebellion” disrupted the passive, objectified image of panda cuteness manufactured by a global cultural industry that thrives on producing and circulating panda-themed commodities.

Fig. 4 Osaka Shinbun article from 13 January 1981 titled, “Wei Wei’s Public Viewing Finally Cancelled”. The subtitles read, “[He is] in a bad mood”, “Children were disappointed”, and “Too excited by a new experience, but will still perform ‘circus tricks’”.

Finally, we have argued that Wei Wei’s resistance to his role as an animal entertainer marked the beginning of a shift in popular understandings of the association between the giant panda and China–Japan friendship during the 1980s. Subsequent media reports on circus pandas no longer portrayed them simply as “children’s toys” or obedient children; instead, they sometimes highlighted the panda’s moodiness and unruliness.104 In parallel, Toho Studios released a feature film, Panda Story, in 1988 to commemorate the fifteenth anniversary of the normalization of Japan–China relations and the tenth anniversary of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship.105 Filmed largely in Jiuzhai Valley National Park in Sichuan Province, the movie centred on the friendship between a young Japanese woman, an Indigenous Tibetan boy, and a male panda cub as they carried out wildlife rescue efforts. Unsurprisingly, Jiao Jiao’s 1989 tour was also assigned “a more important mission than simply showing her circus tricks”.106 Promotional materials claimed that the revenue would be donated to save giant pandas from starvation caused by the flowering and dying of bamboo forests. Thus, nearly nine years after Wei Wei’s debut in Japan, the cultural power of his “rebellion” found fuller expression in new forms of promotion and narration of China–Japan relations: the panda–human co-performance helped reimagine bilateral relations beyond a purely political-economic framework and articulated this friendship through a transnational environmentalist agenda. In contrast to the WWF’s “neotenic branding”107 of its panda logo, these portrayals embraced — if only partially — the agency of nonhuman animals acting according to their own volition.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our research interlocutors and collaborators in China and Japan. They include the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe, which granted one of us an interview access, the Tokyo Office of Japan–China Friendship Association, which kindly offered a copy of a JCFA newsletter, and the event company, Toho, Ltd. in Sendai city, which provided a photocopy of the 1989 SAT tour brochure. We are also grateful to Lu Xing Qi and the sisters at a pharmacy in Akita city who shared their memories about the panda circus. Lastly, our sincere gratitude goes to Rosemary-Claire Collard and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions, which greatly helped improve this work.

Bibliography

Notes

The use of Chinese characters in this text follows national conventions: names of Chinese individuals and pandas are written in simplified Chinese, whereas Japanese names are written in kanji. Japanese individuals’ names and titles are romanized without macrons throughout.

The description of this event is based on a video clip published by The Associated Press: “SYND 30-10-72 Pandas Arrive from China”, YouTube, 21 July 2015, 0:40, https://youtu.be/_120Am_Lb2w.

Associated Press, “SYND 5-11-72 Chinese Hand Over 2 Pandas to Tokyo Zoo in Official Ceremony”, YouTube, 21 July 2015, 0:51, https://youtu.be/uS0Rhw8v4jE.

Miller, Nature of the Beasts, 209.

Itoh, Japanese War Orphans.

Itoh, Japanese War Orphans, Itoh, Pioneers; Soeya, Japan’s Economic Diplomacy, 5–7.

Itoh, Pioneers, 125.

Miller, Nature of the Beasts, 207.

Doi, “Nihon no panda tachi” [“Pandas in Japan”], 122; Ienaga, Chugoku panda gaiko-shi [History of China’s Panda Diplomacy].

Miller, Nature of the Beasts, 213–14. See also, Sato, “From Hello Kitty”; Otmazgin, Regionalizing Culture.

Bouissac, Circus as Multimodal Discourse, 104–14.

Peterson, “Animal Apparatus”, 39.

See this Chinese-language news report on Ying Ying: China News Network, 17 December 2009. https://www.chinanews.com.cn/life/news/2009/12-17/2022493.shtml.

For Basi’s story, see this Chinese-language news article: China Diaspora News Network, 14 September 2017, http://www.chinaqw.com/zhwh/2017/09-14/161542.shtml.

Quotations from interviews with Lu Xing Qi were translated from Chinese to English by one of the authors.

Hoffman, “Reliability and Validity”, 88.

Krebber and Roscher, “Introduction”, 2. Also see Baratay, Animal Biographies.

Ienaga, Chugoku panda gaiko-shi.

Weber, “Diplomatic History”, 198–200. See also Ringmar, “Audience”; Belozerskaya, Medici Giraffe.

Leira and Neumann, “Beastly Diplomacy”, 349.

Ringmar, “Audience for a Giraffe”.

Nicholls, Way of the Panda; Barua, “Affective Economies”.

Quoted in Nicholls, Way of the Panda, 74.

For more on this pair of giant pandas, see: Alexander Burns, “When Ling-Ling and Hsing Hsing Arrived in the U.S”, The New York Times, 4 February 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/07/nyregion/the-pandas-richard-nixon-obtained-for-the-us.html

See Hartig, “Panda Diplomacy”; Zhang, “Pandas”.

Ienaga, Chugoku panda gaiko-shi.

Barua, “Affective Economies”; Brantz “Introduction”; Collard “Panda Politics”; Leira and Neumann, “Beastly Diplomacy”.

Roscher, “New Political History”, 53. See also, Nance, “Introduction”; Vandersommers et al., “Animal History”.

Howell, “Animals, Agency, and History”, 207.

Lorimer, “Nonhuman Charisma”, 915, 918.

Nicholls, Way of the Panda, 98; Lorimer, “Nonhuman Charisma”, 923.

Hochschild, Managed Heart.

McEwen, “‘He Took Care of Me’”; Coulter, “Beyond Human”.

Colling, Animal Resistance; Wadiwel, “Chicken Harvesting Machine”; Hribal, “‘Animals Are Part’”; Nance, Entertaining Elephants.

Almiron et al., “Critical Animal and Media Studies”.

Cole and Stewart, Our Children.

Cole and Stewart, Our Children, 98.

See similar discussions in Swart, “Other Citizens”.

Songster, Panda Nation, 46–47.

Songster, Panda Nation, 59.

Songster, Panda Nation, 81–82.

The filmmaker Chen Tong Yi published a memoir about capturing Wei Wei on the Chinese news network Eastday: http://gov.eastday.com/renda/zgd/node10954/node18759/u1a1823121.html.

This information was drawn from the author’s interview with Zhang Tie Shan’s student, Lu Xing Qi in May 2012. Lu became Wei Wei’s handler.

Fu and Fu, 中国杂技史 [History of Chinese Acrobatics], 211; Wang, “发展中国的马戏艺术” [Developing China’s Circus Arts], 90.

Wang et al., 上海杂技团团史 [Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe], 5–8.

Songster, Panda Nation, 83.

Songster, Panda Nation, 80.

Songster, Panda Nation, 83.

Songster, Panda Nation, 73; Wang et al., 上海杂技团团史 [Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe], 50.

Wang et al., 上海杂技团团史 [Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe], 9–10; Wang, “发展中国的马戏艺术” [Developing China’s Circus Arts], 93.

Zhang, “Bending the Body”.

Between 1967 and 1978, over seventeen million junior and senior high school students were forced to live and work in rural areas under a policy often labelled the “send-down” policy. See Zhou and Hou, “Children of the Cultural Revolution”.

Bunderson and Thompson, “Call of the Wild”; Coleman, “Shoemaker’s Circus”; Bender, Animal Game, 183–87.

While we were finalizing this manuscript, a story about Lu Xing Qi’s experience training Wei Wei was published on China’s Teng Xun News Network. It notes that Wei Wei died in 1992. Tencent Network, 19 August 2024. https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20240819A00RFZ00.

Andrews, Animal Mind; Bekoff, “Animal Emotions”; Masson and McCarthy, When Elephants Weep; Rollin, Unheeded Cry.

Bekoff, “Animal Emotions”, 866–67.

Tait, “Trained Performances”, 69.

Lorimer, “Nonhuman Charisma,” 921.

Bekoff, “Animal Emotions”, 867.

Bouissac, Circus as Multimodal Discourse.

See the clip of Wei Wei’s performance here: https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1cs411v7tP/

Peterson, “Animal Apparatus”, 34.

See a similar discussion on circus animal performance in Tait, “Trained Performances”, 67.

Nicholls, Way of the Panda, 180–81.

Nihon chugoku yuko kyokai, “Shinshun ni subarashii otoshidama”.

Fang, Zainichi kakyo no aidenttiti no henyo [Changing Forms of Identity among Overseas Chinese in Japan].

Akagi, “Japan’s Economic Relations”; Mori, Zaikabo to chugoku shakai [Spinning Factories in China].

Fogel, “Shanghai–Japan”; Henriot, “‘Little Japan’ in Shanghai”.

Han, “True Sino–Japanese Amity?”, 588.

Seraphim, “People’s Diplomacy”.

NGOs launched in this period include the Committee to Commemorate Chinese Prisoners of Worrier Martyrs (1953), the Japan–China Association for Cultural Exchange (1956), and the Liaison Society for Returnees from China (1956). See Seraphim, “People’s Diplomacy”, 204.

Seraphim, “People’s Diplomacy”; Nitchu boeki sokushin kai no kiroku wo tsukuru kai [Association for the Promotion of Japan–China Trade].

Zelinsky, “Twinning of the World,” 6.

Nitchu yuko kyokai, Nitchu yuko undo gojunen [Fifty Years of the Japan–China Friendship Movement], 271. Unless otherwise noted, all Japanese texts cited here were translated into English by one of the authors.

Nitchu yuko kyokai, Nitchu yuko undo gojunen, 392–93.

Tamura, “Jichitai no kokusai koryu” [“International Exchanges”], 263; Sugai, “Jichitai no Kokusai katsudo” [“International Activities”], 224.

Huang and Zhou, 中日友好交流三十年 [Thirty Years of Sino–Japanese Friendship Exchange]; Nihon chugoku yuko kyokai, Nitchu yuko undo no hanseiki [Half-Century of the Japan–China Friendship Movement]; Nitchu yuko kyokai, Nitchu yuko undo gojunen.

Yokohama shanhai yuko toshi koryu junen no ayumi: hito to minato to [Ten Years of Yokohama–Shanghai Friendship-City Exchange: People and Port], 3–21.

Chugoku shanhai zatsugidan nihon judan koen [China’s Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe].

“Kyokugei panda rainichi?” [Will an Acrobatic Panda Come to Japan?] Mainichi Shinbun, 21 March 1979, 22. While Nagano Shigeo had close ties with LDP Prime Minister Ikeda Hayato (池田勇人),the JCFA faction supporting the 1981 SAT tour was connected to the Japan Socialist Party (JSP). Cross-party support made the tour possible.

Sekiguchi, Chugoku keizai wo shindan suru [Assessing the Chinese Economy].

In 1966, political tensions between pro- and anti-Maoist JCFA members split the organization into two groups. The pro-CCP group, which claimed greater authenticity, supported the 1974 and 1981 SAT tours. The other group ceased communication with the Chinese government until 1999. See Nihon chugoku yuko kyokai, ed., Nitchu yuko undo no hanseiki; Nitchu yuko kyokai, Nitchu yuko undo gojunen.

Chugoku shanhai zatsugidan nihon judan koen.

Nihon chugoku yuko kyokai, “Shinshun ni subarashii otoshidama”.

At Yokohama Cultural Gymnasium, reserved-seat tickets sold for 2500 yen; non-reserved seats were 2000 yen for adults and 1000 yen for children. See “Kyokugei panda kyo rainichi” [“The Circus-Trick Panda Arrives in Japan Today”], Kanagawa Shinbun, 24 January 1981, 11. For comparison, an adult cinema ticket in major cities cost approximately 1465 yen, according to retail price data from the Statistics Bureau of Japan (https://www.stat.go.jp/data/kouri/doukou/3.html).

For a comparable analysis, see Cowie, “Elephants, Education and Entertainment”, 115.

Our observation is informed by Mizelle, “Contested Exhibitions”.

The literal translation of the Japanese title is Panda, A Little Panda.

Chugoku shanhai zatsugidan nihon judan koen.

“Kore ga chugoku no bikku suta kyokugei panda no wei wei” [“This Is China’s Big Star, the Acrobatic Panda Wei Wei”]. Shukan Heibon, 1 January 1981.

Sato, “From Hello Kitty”.

“Chibikko ni ureshii otoshidama” [A Delightful New Year’s Gift for Kids]. Shukan Myojo, 4 January 1981; Nihon chugoku yuko kyokai, “Shinshun ni subarashii otoshidama”.

This metaphor suggests that parents bringing children to see Wei Wei was equivalent to offering them otoshidama — annual New Year’s gift money traditionally given to children.

Howell, “Animals, Agency, and History”, 207.

See Daniel Vandersommers’s discussion on runaway animals in “Entangled Encounters”, 68, 90.

“Wei Wei otsukare”. Osaka Shinbun, 10 January 1981.

Gruen, Entangled Empathy.

“Taberunomo nekorobunomo gei nandazotto!” [“Eating and Lying Down Are My Tricks, Too!”]. Myōjō, 6 March 1986.

“‘Ugoku kokuho’ kyokugei panda no weiwei kun rainichi” [“A Moving National Treasure: The Circus-Trick Panda Wei Wei Comes to Japan”], Josei Sebun, 20 February 1986.

“Shanhai zatsugidan ninki mono no totteoki tokuiwaza” [“The Popular Performer’s Special Tricks at the Shanghai Acrobat Troupe”]. Friday, 24 March 1989, 61.

According to the SAT’s self-published history, the Japan tours generated a total of US$ 3,500,000. See Wang et al., 上海杂技团团史 [Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe], 81.

Wang et al., 上海杂技团团史 [Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe], 146, 149.

Minami, “Perspective About the Effect”.

“Taberunomo nekorobunomo gei nandazotto!” [“Eating and Lying Down…”].

Information about the film Panda Story is available on Baidu Internet Encyclopedia: https://baike.baidu.com/item/熊猫的故事/1392756#4

“Shanhai zatsugidan ninki mono no totteoki tokuiwaza” [“Shanghai Acrobat Trope”], 61.

Barua, “Affective Economies”, 681.

Works Cited

Akagi, Roy Hidemichi. “Japan’s Economic Relations with China.” Pacific Affairs 4, no. 6 (1931): 488–510. https://doi.org/10.2307/2750130.

Almiron, Núria, Matthew Cole, and Carrie Packwood Freeman. “Critical Animal and Media Studies: Expanding the Understanding of Oppression in Communication Research.” European Journal of Communication 33, no. 4 (2018): 367–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118763937.

Andrews, Kristin. The Animal Mind: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Animal Cognition. London: Routledge, 2020.

Baratay, Éric. Animal Biographies: Toward a History of Individuals. Translated by Lindsay Turner. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2022.

Barua, Maan. “Affective Economies, Pandas, and the Atmospheric Politics of Lively Capital.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45, no. 3 (2019): 678–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12361.

Belozerskaya, Marina. The Medici Giraffe: And Other Tales of Exotic Animals and Power. New York: Little, Brown, 2006.

Bender, Daniel. E. The Animal Game: Searching for Wildness at the American Zoo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Bekoff, Marc. “Animal Emotions: Exploring Passionate Natures.” BioScience 50, no. 10 (2000): 861–70.

Bouissac, Paul. Circus as Multimodal Discourse: Performance, Meaning, and Ritual. London: Bloomsbury, 2012.

Brantz, Dorothee. Introduction to Beastly Natures: Animals, Humans, and the Study of History, 1–12. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010.

Bunderson, J. Stuart, and Jeffery A. Thompson. “The Call of the Wild: Zookeepers, Callings, and the Double-Edged Sword of Deeply Meaningful Work.” Administrative Science Quarterly 54, no. 1 (2009): 32–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/27749305.

Chugoku shanhai zatsugidan nihon judan koen: sekaino supa aidoru Wei Wei [China’s Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe’s Tour across Japan: The World’s Super Idol Wei Wei]. Nitchu Geikyo and Japan–China Friendship Association, c. 1981.

Cole, Matthew, and Kate Stewart. Our Children and Other Animals: The Cultural Construction of Human–Animal Relations in Childhood. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014.

Coleman, Jon T. “The Shoemaker’s Circus: Grizzly Adams and Nineteenth-Century Animal Entertainment.” Environmental History 20, no. 4 (2015): 593–618. https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/emv102.

Collard, Rosemary‐Claire. “Panda Politics.” The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 57, no. 2 (2013): 226–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12010.

Colling, Sarat. Animal Resistance in the Global Capitalist Era. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2020.

Coulter, Kendra. “Beyond Human to Humane: A Multispecies Analysis of Care Work, Its Repression, and Its Potential.” Studies in Social Justice 10, no. 2 (2016): 199–219. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v10i2.1350.

Cowie, Helen. “Elephants, Education and Entertainment: Travelling Menageries in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Journal of the History of Collections 25, no. 1 (2013): 103–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhr037.

Doi, Toshimitsu. “Nihon no panda tachi” [“Pandas in Japan”]. In Panda to watashi [Panda and Me], edited by Kuroyanagi Tetsuko and Nakama Tachi, 102–114. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbun Shuppan, 2022.

Fu Qi Feng and Fu Teng Long. 中国杂技史 [A History of Chinese Acrobatics]. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Press, 2004.

Fang, Guo. Zainichi kakyo no aidenttiti no henyo [The Changing Identity of Overseas Chinese in Japan]. Tokyo: Toshindo, 1999.

Fogel, Joshua A. “‘Shanghai-Japan’: The Japanese Residents’ Association of Shanghai.” The Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 4 (2000): 927–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/2659217.

Gruen, Lori. Entangled Empathy: An Alternative Ethics for Our Relationships with Animals. New York: Lantern Books, 2015.

Han, Eric. “A True Sino-Japanese Amity?: Collaborationism and the Yokohama Chinese (1937–1945).” The Journal of Asian Studies 72, no. 3 (2013): 587–609. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911813000533.

Hartig, Falk. “Panda Diplomacy: The Cutest Part of China’s Public Diplomacy.” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 8, no. 1 (2013): 49–78. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-12341245.

Henriot, Christian. “‘Little Japan’ in Shanghai: An Insulated Community, 1875–1945.” In New Frontiers: Imperialism’s New Communities in East Asia, 1842–1953, edited by Robert Brickers and Christian Henriot, 146–69. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Hoffman, Alice. “Reliability and Validity in Oral History.” In Oral History: An Interdisciplinary Anthology, edited by David K. Dunaway and Willa K. Baum, 87–93. Walnut Creek, CA: Sage, 1996.

Howell, Philip. “Animals, Agency, and History.” In The Routledge Companion to Animal–Human History, edited by Hilda Kean and Philip Howell, 197–221. London: Routledge, 2018.

Hribal, Jason. “‘Animals are Part of the Working Class’: A Challenge to Labor History.” Labor History 44, no. 4 (2003), 435–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656032000170069.

Huang Dahui, and Zhou Yingxin, eds. 中日友好交流三十年, 1978–2008. 文化教育与民间交流卷 [Thirty Years of Friendly Sino–Japanese Exchange, 1978–2008: Cultural, Educational, and Folk Exchange]. Beijing: Social Science Literature Publishing House, 2008.

Ienaga Masayuki. Chugoku panda gaiko-shi [The History of China’s Panda Diplomacy]. Tokyo: Kodansha, 2022.

Itoh, Mayumi. Japanese War Orphans in Manchuria: Forgotten Victims of World War II. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Itoh, Mayumi. Pioneers of Sino-Japanese Relations: Liao and Takasaki. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Kagotani, Naoto. “The Chinese Merchant Community in Kobe and the Development of the Japanese Cotton Industry, 1890–1941.” In Japan, China and the Growth of the Asian International Economy, 1850–1949 edited by Kaoru Sugihara, 49–72. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Krebber, André and Roscher, Mieke. “Introduction: Biographies, Animals and Individuality.” In Animal Biography: Re-Framing Animal Lives, edited by André Krebber and Mieke Roscher, 1–15. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Leira, Halvard, and Iver B. Neumann. “Beastly Diplomacy.” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 12, no. 4 (2017): 337–59. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-12341355.

Lorimer, Jamie. “Nonhuman Charisma.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 25, no. 5 (2007): 911–32. https://doi.org/10.1068/d71j.

Masson, Jeffrey Moussaieff and Susan McCarthy. When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals. New York: Dell Publishing, 1995.

McEwen, Andrew. “‘He Took Care of Me’: The Human–Animal Bond in Canada’s Great War.” In The Historical Animal, edited by Susan Nance, 272–88. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2015.

Miller, Ian Jared. The Nature of the Beasts: Empire and Exhibition at the Tokyo Imperial Zoo. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013.

Minami, Hiroshi. “The Perspective about the Effect that a Big Event Gives for Regional Economy.” Japanese Journal of Real Estate Sciences 28, no. 1 (2014): 36–41.

Mizelle, Brett. “Contested Exhibitions: The Debate over Proper Animal Sights in Post-Revolutionary America.” Worldviews 9, no. 2 (2005): 219–35. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568535054615367.

Mori Tokihiko, ed. Zaikabo to chugoku shakai [China-based Spinning Factories and Chinese Society]. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press, 2005.

Nance, Susan. Entertaining Elephants: Animal Agency and the Business of the American Circus. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

Nance, Susan. Introduction to The Historical Animal, edited by Susan Nance, 1–15. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2015.

Nicholls, Henry. The Way of the Panda. New York: Pegasus Books, 2012.

Nitchu boeki sokushin kai no kiroku wo tsukuru kai. Nitchu boeki sokushin kai: Sono undo to kiseki [Association for the Promotion of Japan–China Trade: Its Movement and Trajectory]. Tokyo: Dōjinsha, 2010.

Nihon chugoku yuko kyokai, “Shinshun ni subarashii otoshidama” [“A Wonderful New Year’s Gift”]. Nihon to Chugoku [Japan and China], 1 January 1981, 16.

Nihon chugoku yuko kyokai, ed. Nitchu yuko undo no hanseiki: sono ayumi to shashin [Half a Century of the Japan–China Friendship Movement: Its History and Photographs]. Tokyo: Keyakisha, 2000.

Nitchu yuko kyokai, ed. Nitchu yuko undo gojunen [Fifty Years of the Japan–China Friendship Movement]. Tokyo: Tohoshoten, 2000.

Otmazgin, Nissim Kadosh. Regionalizing Culture: The Political Economy of Japanese Popular Culture in Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2013.

Peterson, Michael. “The Animal Apparatus: From a Theory of Animal Acting to an Ethics of Animal Acts.” TDR 51, no. 1 (2007): 33–48.

Ringmar, Erik. “Audience for a Giraffe: European Expansionism and the Quest for the Exotic.” Journal of World History 17, no. 4 (2006): 375–97.

Rollin, Bernard E. The Unheeded Cry: Animal Consciousness, Animal Pain and Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Roscher, Mieke. “New Political History and the Writing of Animal Lives.” In The Routledge Companion to Animal–Human History, edited by Hilda Kean and Philip Howell, 53–75. London: Routledge, 2018.

Sato, Kumiko. “From Hello Kitty to Cod Roe Kewpie: A Postwar Cultural History of Cuteness in Japan.” Asian Intercultural Contact 14, no. 2 (2009): 38–42.

Sekiguchi, Sueo. Chugoku keizai o shindan suru [Assessing the Chinese Economy]. Tokyo: Nihon keizai shinbunsha, 1979.

Seraphim, Franziska. “People’s Diplomacy: The Japan–China Friendship Association and Critical War Memory in the 1950s.” In Routledge Handbook of Memory and Reconciliation in East Asia, edited by Mikyoung Kim, 196–211. London: Routledge, 2016.

Serikawa Yugo, dir. Panda no daiboken [The Panda’s Great Adventure]. Toei, 1973.

Shinjo Taku, dir. Panda monogatari [Panda Story]. Toho, 1988.

Soeya, Yoshihide. Japan’s Economic Diplomacy with China, 1945–1978. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.