New York City’s Beloved Owl

Humanimalia 15.2 (Summer 2025)

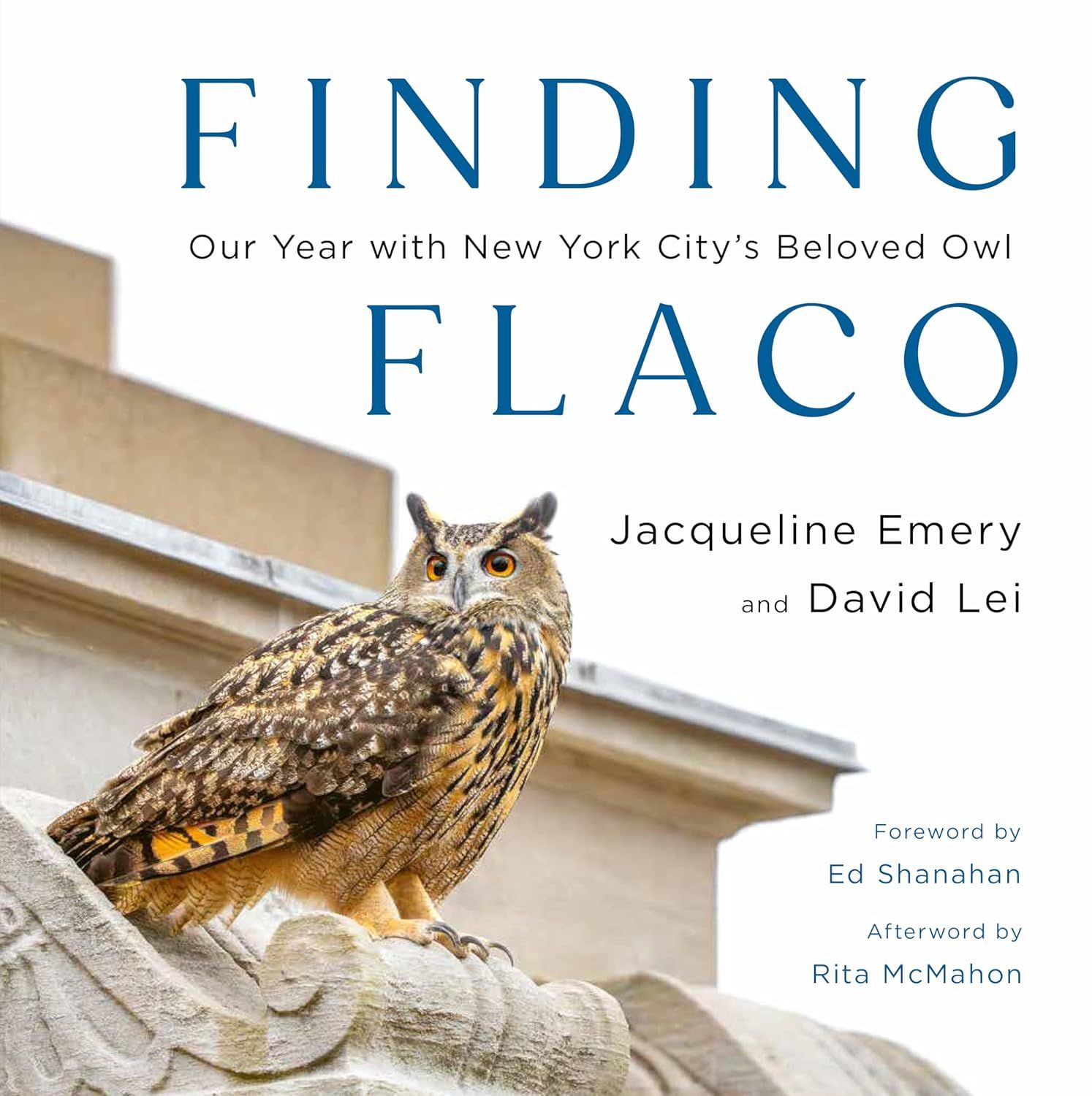

In their large, stunning photography book Finding Flaco: Our Year with New York City’s Beloved Owl, authors and photographers Jacqueline Emery and David Lei chronicle their first-hand, year-long account of following Flaco, a 4.1-pound (1.8 kg) Eurasian eagle-owl with a wingspan of over six feet (1.80 m) who escaped from his small enclosure at the Central Park Zoo. They explain that, after finishing a day’s work, Emery and Lei would head to Central Park on their electric bikes equipped with binoculars, cameras, phones, tips, and a thermal monocular to find Flaco. Soon they would drive what they called the “hoot route”, finding Flaco at many of his favourite Upper West Side perches. Their narrative and photography touches upon the themes of perception, transformation, agency, beauty, community, and hope. The profusion of these themes is made fitting by one photograph in particular, in which Flaco rests near a statue of Pomona, the Greek goddess of abundance. This image suggests that Flaco awakened in Emery and Lei a much-needed cultural myth of meaningful abundance — he became a “symbol of freedom, hope, resilience”, an “outsider or underdog”, and even “a magical and mythical being” (203).

Flaco’s journey in the city began on 2 February 2023, when someone entered the Central Park Zoo at night and cut open the metal mesh of Flaco’s small enclosure. To date, this person has not been identified. Flaco’s only view outside was through the enclosure’s skylight, metal mesh and a clear plexiglass barrier that separated him from visitors. The opening allowed him to escape a lifetime of captivity. Flaco hatched at a bird park in North Carolina in 2010 and was the only fledgling transferred to the Central Park Zoo. Emery and Lei explain that, after the wire of his cage was cut, “innocent” Flaco had been “thrust into the wild” (26). They hoped that Flaco would be rescued — after all, he was born in captivity and lived that way for thirteen years. Had his wings atrophied? Would he starve? Could he survive New York’s traffic? Yet as Flaco adapted to the city’s particular wildness, Emery and Lei began to shift their views regarding his perceived vulnerability. Neither “a helpless zoo animal” (25), nor a “victim” (49), Flaco was a “wild owl” (186) who quickly engaged in predation, recovered a nocturnal sleep pattern, developed his flying skills and more. “Before our eyes,” they explain, “Flaco had discovered his wildness” (12) and “had reinvented himself” (36).

Flaco demonstrated unexpected agency. Resisting capture, he established various roosting locations, living “the life he chose for himself on his own terms” (183). Emery and Lei confess to have underestimated Flaco’s adaptability, resilience, and intelligence. They describe his curiosity, hunting efficiency, and favourite spots in the city, and even how he once listened to a couple break up. Above all else, Emery and Lei also admire Flaco’s beauty: “as night began to fall, fireflies would light up around him, adding to the magical feeling of being in his presence on those summer nights and making us almost forget that we were standing in the middle of Manhattan” (102). It is “almost”, though, that is the operative word here, for as much as the hoot route estranges Emery and Lei from the city, it also unlocks for them a new way of seeing and being in it. Finding Flaco thus evokes a strong sense of place; its vivid photographs and maps reveal a city recast through an owl’s eye view.

Emery and Lei cheered Flaco’s freedom, joining a “shared experience of curiosity and concern” (25) with other New Yorkers. For a time, Flaco became an animal celebrity who inspired admirers and followers. Finding Flaco pays tribute to this community by including photographs, poetry, and art from other New Yorkers who were inspired by Flaco. Among these are the poem “Flaco the Owl” by poet Joseph Fasano and a spray paint mural of Flaco by graffiti artist Nite Owl. Flaco’s “presence was a gift to every person who saw him”, Emery and Lei write (148). They explain that “holding those deep orange eyes in a mutual gaze, we saw something about ourselves too” (148). The book’s title thus has many resonances. More than just a plain description of Emery and Lei’s attempts to locate and photograph Flaco, it names a journey toward animal appreciation, a labour of attentiveness, and a community-making adventure. Listening for his distinct hoots, looking for his white throat patches, Emery and Lei worked to find Flaco. Once found, the reward was getting “to stay with [Flaco] until sunset” (191), to witness a “sliver of golden light shining on him” (133), or to find a feather shed from Flaco’s plumage. An image of his feather, on the last page of the book, brought a tear to this reviewer’s eye. Not everyone was patient though. The authors recount a moment when they warned a fellow photographer that Flaco did not appreciate people coming too close; when the photographer pushed beyond the owl’s level of comfort, he not only flew away but never returned to the courtyard. Emery and Lei assert that the “selfish” photographer “cheated herself and the rest of us out of something truly special” (171).

Emery and Lei’s attentiveness to Flaco raised their consciousness about the urban dangers he faced, from rodenticides to collisions with “canyons of glass” (200). In the end, both were responsible for his death. After a year and three months of freedom, Flaco “either flew into or fell from a building as a result of lethal levels of rodenticides and a pigeon-borne virus in his system” (12). Flaco was found dead, face down in an Upper West Side courtyard with traumatic injuries. A necropsy report conducted by the Bronx Zoo revealed that Flaco had suffered from collision trauma, “severe pigeon herpes virus”, and “exposure to four different anticoagulant rodenticides” that New York City regularly uses (193). From this, the authors conclude that Flaco’s short life leaves a legacy of action and hope. They touch upon how New York State Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal renamed a sponsored act (Feathered Lives Also Count) in honour of Flaco, which would require bird-friendly design and “lights out” legislation to mitigate bird deaths by building collision (205). The New York City Council also passed Flaco’s Law no. 1, which would study the use of rat contraception in place of rodenticides. Council members have also proposed Flaco’s Law nos. 2 and 3 regarding the reduction of light pollution and use of reflective glass for buildings. Flaco thus stands, for Emery and Lei, as both a model and a warning. His story, lovingly re-presented in this beautiful book, calls upon readers to share the world with nature.

Flaco’s story also raises questions about what it takes to care for captive animals. Emery and Lei touch upon the small size of Flaco’s enclosure; they question if Flaco had enrichment activities; and they quote an ecologist who reports that “I have often observed that when the power of choice is returned to them, animals prefer to take their chances in a free-living existence” (60). However, during Flaco’s memorial service, held at his favourite oak tree in Central Park in 2024, Lei gave a speech in which he asserted that Flaco’s death mattered more because he was not simply a zoo animal, but an animal who “had discovered his wildness” (12). It’s a salient comment about implied public indifference regarding zoo animals. But it also forces us to ask why Flaco didn’t garner attention when he was confined at the Central Park Zoo. Film director Penny Lane suggests that Flaco activated an already latent public animosity towards zoos: “if we all think that zoos are fine, then why do we all root for any animal that gets loose from a zoo never to go back?” (182). But this might underestimate the role of sentimentality in the narrative of freedom that became the prevailing story of Flaco’s escape. “Flaco was never simply an owl”, Emery and Lei assert, but rather “a symbol of freedom, of hope, and of resilience” (203). Flaco became, in other words, a metaphor for “outlaw”, “underdog”, and “folk hero” (8, 49) that seems to have obscured his agency and importance when he was simply perceived as a zoo animal. More than this, Emery and Lei’s account suggests that people loved Flaco because he had become a charismatic individual: de-anonymized from the moment he left his cage, he became character, personality, celebrity. Animal individuals who resist social trappings can become inspirational figures, as Sarat Colling argues.1 Flaco’s story therefore implies a tension between the affordances of concern between free individuals and the encaged others still in the city’s zoo.

Yet Flaco’s story nevertheless stands as a cut in the mesh of captivity. An opening, albeit small, may prompt readers to recognize the collective imprisonment of nonhuman animals rather than simply perpetuate the cult of individual celebrity with its paparazzi. It may also push beyond Emery and Lei’s own politics. They use their author’s note to announce that they are “not opposed to animals being held in captivity by zoos and other organizations for scientific research, public education, and conservation so long as they are housed in good conditions and allowed to behave naturally” (9). Yet readers will find more than enough evidence in Emery and Lei’s telling of Flaco’s story to doubt this framing. Finding Flaco documents one owl’s journey from zoo animal to local celebrity, and in doing so, points to the agency and importance of those animals that remain anonymous, at least for now.

Notes

Sarat Colling, Animal Resistance in the Global Capitalist Era (East Lansing: Michigan University Press, 2021), 84.