“My Kingdom for a Barking Dog!”

A Critical History of Sheepdog Trialling with Border Collies, and Why It Matters to Sheep

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.20155

Keywords: sheepdog trials; herding dogs; border collies; shepherding; sheep welfare

Bert Theunissen is emeritus professor of history of science and former director of the Descartes Centre for the History and Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities at Utrecht University. His research field is the history of the life sciences in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with special interest in the history of breeding and farm animal breeding cultures. His latest book is Beauty or Statistics: Practice and Science in Dutch Livestock Breeding 1900–2000 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020).

Email: l.t.g.theunissen@uu.nl

Humanimalia 15.2 (Summer 2025)

Abstract

Abstract: According to Raymond and Lorna Coppinger, experts in canine behaviour, sheepdog trialling with Border Collies is mostly for fun. The British International Sheep Dog Society (ISDS), however, contends that trialling has the practical aim of improving the collie as a working dog. So who is right? I take a historical approach to answer this question, using the wealth of data contained in The Field, a magazine established in 1853, to investigate the sport’s history and relation to practical shepherding. Trialling in Britain started in 1873, and in the following decades, the dogs and shepherds’ trialling behaviour underwent a stylization that has clear overtones of genteel notions of manliness. Soon after the first trials, however, critics pointed out that the collies’ specific working style made them less, rather than more suitable for practical shepherding. Other critics objected that the course design did not reflect daily farm work and that training for the trials placed an unacceptable burden on the sheep. In response, the ISDS, established in 1906, restructured the trials to make them more “workmanlike”. This did not end the discussion of their usefulness, however, which continued unabated. Today, in Britain and other sheep farming countries, many shepherds are critical of the trial collie and prefer a different type of dog. The trial collie, I conclude, is to be seen as a sporting dog, bred specifically for trialling. Their use is indeed mostly for fun. In the final section, I raise questions with respect to trialling and sheep welfare. I will discuss an alternative approach to shepherding in which the sheep are not driven but led by the shepherd. This alternative has practical merits and benefits sheep welfare.

In Dogs, their seminal book on canine behaviour and evolution, Raymond and Lorna Coppinger professed that the “use of sheepdogs […] is mostly for fun”.1 This claim will doubtless strike many British sheep farmers as preposterous. To their mind, sheepdogs are working dogs without whom, as shepherd-poet James Hogg put it, “the pastoral life would be a mere blank”.2 As appears from the context, the type of sheepdog the Coppingers had in mind was the border collie, and the “fun” they referred to was sheepdog trialling, which over the last century has grown into a worldwide sport. Seen in this way, their claim is perhaps less unreasonable, yet the point still stands that the indispensability of herding dogs for sheep farmers seems hard to deny. Moreover, according to the British International Sheep Dog Society, the purpose of competitive trialling has always been, and still is, of a practical nature: the improvement of the collie as a working dog.3 Thus the question presents itself to what extent, if at all, the Coppingers’ assessment holds water. In this paper I take a historical perspective to shed light on the issue. My analysis raises questions about the British style of shepherding with herding dogs, which I also aim to elucidate from a historical angle.

Through their performance in the trials as well as their appearance in TV shows, films, and books, border collies have achieved the status of the proverbial sheepdog, at least in the eyes of the general public. Promoters of the breed have touted the collie as the best herding sheepdog in the world and one of the “great success stories of British agriculture”.4 Yet agricultural and cultural historians have paid remarkably little attention to the breed’s history and the backgrounds of sheepdog trialling. Mike Worboys, Julie-Marie Strange, and Neil Pemberton have described the emergence of the collie as a show dog in the late Victorian period, and Margaret Derry has analysed the collie’s transatlantic rise as a show dog in the context of the commercialization of pedigree breeding in the early twentieth century.5 The British sheepdog trials, initiated by genteel landowners in 1873, are central only to Albion Urdank’s investigation of what he called the “rationalization” of the trials in the twentieth century. Urdank argued that the competitions became less sensationalist and more “workmanlike” after 1906, when the British International Sheepdog Society began to organize trials.6 Few details about the earlier history of the trials have been published, however, and the first part of my paper aims to fill this gap by an analysis of the rich and largely unexplored data contained within the now partially digitized The Field, or Country Gentleman’s Newspaper, a weekly magazine established in 1853. Its pages contain well over a hundred reports and comments on the sheepdog trials during the first four decades of their existence, and they shed new light on the early history of the sport and its relation to practical shepherding.7

A short explication of the meaning of “sheepdog” in Victorian Britain is helpful to begin with; the first section thus introduces the main varieties. Only dogs with a particular set of behavioural characteristics proved to do well in the competitions, and over the years sheepdogs of the collie type turned out to best fit the requirements of trialling. Selective breeding further enhanced their herding style, resulting in the distinctive modus operandi of the trial collie. Not only the dogs’, but also the shepherds’ conduct on the course underwent a stylization. A specific choreography of trialling emerged, and there were clear overtones of genteel notions of manliness in the pas de deux performed by shepherd and dog.

This development was not welcomed from all sides, and critical comments soon began to appear in The Field. Recurring elements in these critiques were that the course design did not reflect the daily routines at the farm, that the style of shepherding preferred by the judges made the dogs less suitable for their work, and that the training required in preparation for the trials placed an unacceptable burden on the sheep. The International Sheepdog Society’s efforts to rationalize the trials appear to be a response to this criticism. As we will see, however, the restructuring of the trials did not end the discussion on their practical usefulness, which has continued to this day. Many British shepherds did not consider the trial collie to be the type of dogs they needed. Outside Britain, shepherds in the major sheep-farming countries either had no need for a herding sheepdog or preferred a different kind of dog. The trial collie, I conclude, is to be seen as a sporting dog, bred especially for the purpose of trialling.

In the final section I argue that the trials should raise questions, especially when we switch perspectives to the involuntary participants in the sport: the sheep. Is it acceptable to coerce them to partake in the competitions for the mere purpose of entertainment? The question is the more germane because, as I will argue, the border collie’s herding style is an example of British exceptionalism gone global as a consequence of the trials’ success, while there is an alternative, more sheep-friendly approach that has for ages been the worldwide default in shepherding.

British Sheepdogs and Their Behaviour

Nineteenth-century British sheepdogs came in two general forms: a larger one, for driving sheep or cattle to the market or the slaughterhouse, and a smaller one, for herding flocks in the field. Until the second half of the century, there were no standardized breeds, and working dogs were mostly defined on the basis of their function.8 Thus, a dog keeping the flock together on its route to town was a drover dog, and a dog assisting shepherds with their daily routines was a shepherd dog. If there was anything else that characterized the two types, it was their variability. Descriptions of sheepdogs in contemporary literature on British dogs reflect this: authors distinguished the functional categories of droving and herding dogs, but accounts of what they looked like seem largely based on the local varieties the authors happened to know from their own experience.

Drovers, also called curs, were depicted as dogs with shaggy or smooth grey-and-white coats, although different coats and colours were not excluded.9 Some drovers were naturally stump-tailed; most had their tails docked. Their frequent barking and dexterity in nipping the hocks of cattle without getting kicked were said to be essential to get and keep a flock or herd moving. The smaller shepherd dogs might be rough or smooth-coated, and their colours were usually combinations of black and white, sometimes with tan markings. They were less noisy, but able to bark on command.

Fig. 1 “Cur Dog” or drover.

In Beilby and Bewick, A General History of Quadrupeds, 1790, 286.

Fig. 2

“Drover’s Dog”.

In Allen, Domestic Animals, 1848, 212.

The dividing line between the two types was anything but sharp, and some illustrations are confusing rather than illuminating. Controlled mating in working dogs must have been difficult to achieve, particularly in the case of drover dogs, who travelled through villages and towns, where it was part of their job to protect their charges against the local dogs.10 Thus, there will have been many dogs of mixed ancestry — some authors considered the drover to be a composite type (“cur”) anyway. Furthermore, on small holdings, versatile dogs would have been preferred over specialized ones. Several authors indeed noted that many dogs were expected to perform multiple tasks besides herding livestock, such as guarding the yard, vermin control, and small game hunting (or poaching).

All this is not to say that the British sheepdog population was an inextricable jumble of mongrels. As indicated, drovers were bigger, and they needed power and stamina to drive large flocks — if necessary, for days on end — while the smaller shepherd dogs had to be agile and biddable to the shepherd’s commands. Moreover, different dogs were required in different geographical regions. Depending on the specifics of their task, recognizable types of sheepdogs were used in, for instance, the Downs, the border counties of England and Scotland, and the Scottish Highlands. They were known for their specific capabilities and had local names, such as the Smithfield Drover, the Welsh Grey, and the Highland Collie.11

Even though discussions of most breeds’ exact origins are bound to dissolve in speculation, it is plausible that shaggy-coated drovers contributed to what would come to be called the Old English Sheepdog or Bobtail in the late nineteenth century. Similarly, early illustrations of gathering and herding dogs used in the border counties and the Scottish Highlands (where they were called “coallys” or “colleys”) often show a convincing resemblance to the collies that were later to perform in sheepdog trials. It was probably this type of dog, particularly the foxy-headed Scottish variety, that was mainly used in breeding the Rough and Smooth Collie, the show varieties of the herding sheepdog, in the final decades of the nineteenth century.

Fig. 3 “The Shepherd’s Dog”.

In Beilby and Bewick, A General History of Quadrupeds (1790), 284; “Coally” in the fifth edition (1807), 329.

Fig. 4 “Scotch sheep dog” or “Highland colley”.

In Youatt, The Dog (1845), 63.

Furthermore, in Scotland and several English regions, a shaggy-coated type of dog of intermediate size was used, whose behaviour was somewhere between that of drover and shepherd dogs. Descriptions and photographs of these “beardies”, as they were called, suggest a mixed drover-collie origin.12

To a certain extent, the typical trialling behaviour of the modern border collie — the name that gained currency after the First World War to distinguish the working collie from the show varieties — is a product of selection for the sheepdog trials. The collie’s herding conduct is based on a number of distinct ‘motor patterns’, as the Coppingers defined them, which were enhanced and fine-tuned by selective breeding.13 However, as appears from sources dating from long before the trials were instituted, the collie’s characteristic conduct was not created by late nineteenth-century shepherds. For instance, the earliest book on British dogs, John Caius’s Of Englishe Dogges from 1576, contains a clear description of a sheepdog gathering and driving sheep on the shepherd’s command:

This dogge either at the hearing of his masters voyce, or at the wagging and whisteling in his fist, or at his shrill and horse hissing bringeth the wandring weathers and straying sheepe, into the selfe same place where his masters will and wishe is to have [them], wherby the shepherd reapeth this benefite, namely, that with litle labour and no toyle or moving of his feete he may rule and guide his flocke, according to his owne desire, either to have them go forward, or to stand still, or to drawe backward, or to turne this way, or to take that way.14

Farmer and agricultural writer William Ellis, in The Shepherd’s Sure Guide (1749), noted that a sheepdog should obey every whistled command, bark when asked, collect the sheep for folding at night, and make sure they stayed clear of arable fields. If the shepherd wished to inspect a single ewe, the dog should seize her by the ear and hold her till the shepherd arrived. The principal adage of good flock management was to leave the sheep in peace as much as possible, so they could graze and grow. Therefore, Ellis wrote, a “lame Shepherd, and a lazy Dog, are accounted the best Attendants on a Flock of Sheep, because they necessarily drive them leisurely [and] give the Sheep their due time of Feeding”. Admittedly, he added, there was a difference between, on the one hand, enclosed pastures, where less shepherding was needed and hedges and fences made driving the sheep easy, and, on the other hand, the open fields in common land, where the flocks of different shepherds grazed together. In the open commons, a “nimble shepherd” and a “nimble dog” were required to keep the flocks apart and prevent them from ravaging the arable plots. Still, it was essential for a sheepdog never to go after the sheep without good reason. A dog with too much “Courage” might ruin the flock.15

Ralph Beilby and Thomas Bewick, in their General History of Quadrupeds (1790), and Sydenham Edwards, in his Cynographia Britannica (1800), both described in detail how sheepdogs managed to fetch sheep even when they were far away and out of sight. In driving them, Edwards wrote, the dog should keep perfect balance: “Sheep on mountainous regions are swift as Roes. If well taught he never approaches too nigh, but hovering round presents himself wherever his presence is necessary”. If the sheep bolted, the dog “flies before for fear of separating them, makes half circles and meets them in front”. A good dog, he added, “never offers injury, attacks but to restrain, and pursues but to guide. The best kinds run perfectly silent”.16

The importance of calm and measured shepherding was reiterated by later authors. In a treatise on the management of mountain sheep from 1815, John Little noted that a “hasty passionate man, with a rash dog” made for bad shepherding. It took a “calm [and] good tempered man, with a sagacious close mouthed dog” for the flock to thrive.17 In the same vein, William Youatt stated in 1845: “In open, unenclosed districts, [sheepdogs] are indispensable; but in others I wish them, I confess, either managed, or encouraged less”. A drover dog might occasionally need to nip a sheep, but this “will admit of no apology in the shepherd’s dog”.18 In 1846, Charles St. John added that a sagacious dog, in his first approach of the sheep, did not dash right at them but made a wide arc, ending up behind them to drive them in the required direction. St. John also recorded the sheepdog’s ability to separate a sheep from the flock and catch them.19

Shepherd James Scott of Ancrum, an early competitor in the sheepdog trials, suggested that the famous ‘eye’, the mesmerizing gaze collies deploy to impose their will on sheep, was a recent phenomenon. The first time he ever saw a dog use it was in 1875, two years after the first recorded trials.20 However, James Hogg’s Shepherd’s Calendar of 1829 had already recorded the sheepdog’s characteristic glaring at the sheep. Or, rather, at any animal, as Hogg’s dog Hector would not only eye-stalk sheep, but also the farm cat: “Whenever he was within doors, his whole occupation was watching and pointing the cat from morning to night”.21

So, it is clear that the sheepdog trials that began in 1873 were not responsible for the creation of the modern collie’s typical herding behaviour. The most notable elements were displayed much earlier by at least some dogs from the regions where, as Thomas Brown wrote in 1829, “his services are invaluable”, that is “in the north of England, and in the Highlands of Scotland”.22 Still, the trials stimulated selective breeding for this type of herding conduct, resulting in its enhancement and stylization. As we will see, the shepherds’ behaviour would also undergo stylization during the early decades of the trials. This process included the suppression of aspects of everyday herding routines that shepherds and sheepdogs were emphatically not supposed to display on the trial course.

The First Trials at Bala

The first officially recorded British sheepdog trials were held on October 9, 1873, on the slopes of Garth Goch near Bala, a Welsh market town.23 The event took place under the patronage of the upper classes: the organizing committee included, among others, Viscount Combermere, the Marquis of Exeter, and Viscount Downe. The social significance of events of this kind, as meeting places for the classes that consolidated the social hierarchy, was perceptively pointed out by Rawdon Lee, in his A History and Description of the Collie (1890):

In these times of peculiar changes no stone should be left unturned that is likely to sustain the good feeling not always prevailing between landowner and tenant […] Without going quite so far as to suggest such competitive trials as a panacea for political unpleasantness and agricultural depression, there is no doubt [such meetings] bring the land occupier and the land owner into touch with each other, provocative of friendliness that can scarcely be secured by any other means.24

Urdank rightly noted that the trials initially showed a clear resemblance to the Kennel Club’s dog shows, the first of which was held in 1859.25 One of the initiators of the Bala event was Sewallis Shirley, the founder of the Kennel Club, and it may have been on his suggestion that the trials did not only test the dogs’ working abilities, but also included a competition for the best-looking sheepdog. From a practical perspective, however, the sheepdog trials rather shared their motivation with the gun dog field trials organized by the gentry since 1866.26 The aims the Bala committee set itself were not explicitly stated but a few years later the organizers of sheepdog trials at Ulverston put the goal in these words: “to induce greater attention to the breeding and training of these useful dogs”.27 Thus, the trials’ purpose shared a key element with that of the gun dog trials. The latter were organized in reaction to complaints about the show ring, in which working ability played no role. For gun dogs, it was felt, this would not do: the aim of breed improvement through competition could only be reached if the dogs’ performance in the field was also tested.28 For sheepdogs the situation was no different: they also appeared in the show ring and the detrimental effect this might have on their working ability was a broadly shared concern.29 “Dog shows have added to the beauty of the collie; trials must add to his intelligence”, Rawdon Lee stated succinctly.30

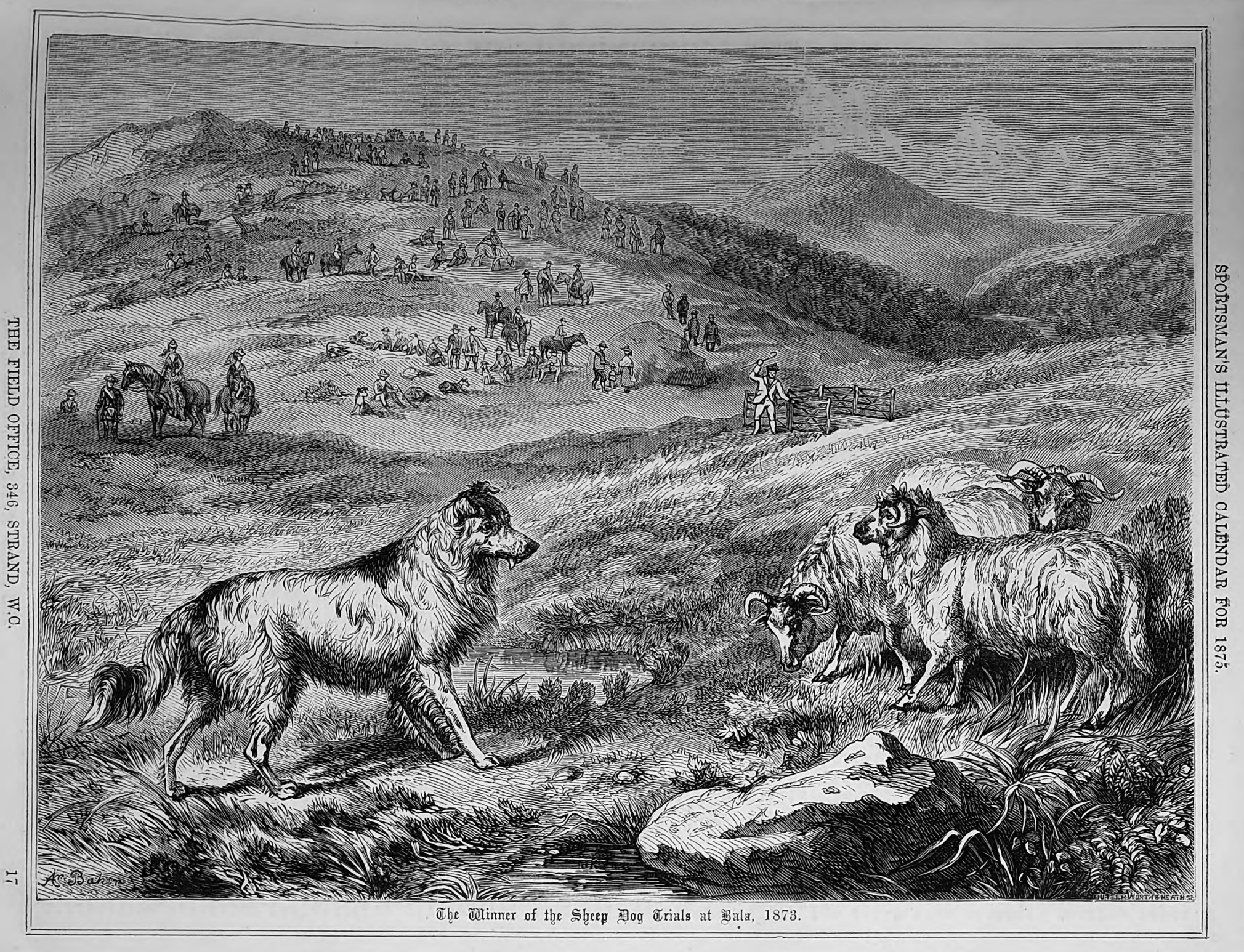

The report of the first trials at Bala in The Field conveys that the reality of shepherding had not yet reached the level of sophistication desired by the authors discussed above.31 Of the ten competing dogs, who showed as much variability in their size and looks as in their approach to the task at hand, only a few succeeded in fulfilling it. As with the gundog trials, the competition was held in two rounds: the first intended to eliminate weaker contenders, the second to appoint a winner. In the first heat, three sheep had to be driven into a small pen made of hurdles. The sheep — of a flighty Welsh mountain type — were released at a distance of five hundred yards from the pen. The dog had to collect them, drive them to the pen and, with the assistance of the shepherd, make them enter it. In the second round, three sheep were released at a distance of eight hundred yards, and the dog had to fetch them, drive them through a gate, and bring them to the shepherd. No time limit was mentioned, but the judges could decide to end a run at their own discretion if it took too long.

Only two dogs succeeded in penning their sheep: Tweed, a small black and tan Highland collie, and Sam, a black dog with a white collar from North East England. The other dogs lost one or more of their charges, either right at the start or at the pen, the sheep bolting in all directions or disappearing among the spectators. Quite a few triplets refused to be driven away from the corner of the field where the other sheep were penned. Some dogs seemed not up to the task of driving a small lot of three at all. One dog, instead of circling the sheep, merely ran after them, and another could not even keep up with the agile mountain sheep. The Field’s reporter deemed one of the competing dogs “to yelp too much”. Another dog bit a particularly “nasty” sheep, and a ewe that had jumped into a stream bordering the trial course was hauled out by the dog by the scruff of her neck.

The shepherds made no bones about improvising either: one of them lifted his dog over a wall to get to his targets, and another penned a sheep by chucking them in himself. A particularly tiny canine was lifted high into the air by the shepherd to enable him to sight his sheep. During the runs, if shouted or whistled commands proved ineffective, some shepherds resorted to a different register: a local contestant entertained the crowd with what the reporter qualified as “excellent witticisms in Welsh”. The judges also saw fit to intervene on one occasion, when an uncharacteristically cooperative triplet was felt to make things too easy for the dog; they ordered the shepherd to disperse them, so as to enable the dog to show his cunning.

The four dogs selected to compete in the second round demonstrated, to varying degrees, “what ought to be done and the way to do it”, according to the reporting journalist. Tweed displayed “wonderful obedience” and kept his distance in circling the sheep, “coming leisurely and without frightening [them]”. Sam impressed the spectators by dropping instantly to command and by his “crouching like a panther” at the pen. He may even have controlled the sheep with his “eye”: the chronicler noted how he seemed to be “fettering them with his eye”. The crowd cheered loudly at Sam’s performance, but he only won third prize, because it was one of his sheep who had jumped into the water, and his rescue efforts had taken too much time. Tweed was awarded first prize, and he also won the beauty contest. Sam’s qualities did not go unnoticed, however, because a year later he was sold to an Australian farmer.32 He would not be the last prize winner to change hands after a trial.

Fig. 5 “The Winner of the Sheep Dog Trials at Bala, 1873.”

In The Rural Almanac & Sportsman’s Illustrated Calendar for 1875 (London: Field Office), 17.

The Field’s account of the Bala trials shows that the rules of the game had not yet been set in stone. Neither the shepherds and their dogs, nor the organizers and judges seemed to have had a clear idea of what to expect and what was expected of them.33 There were no penalties for undesirable behaviour on the dog’s or handler’s part, and the jury mainly intervened if a run took up too much time. On the other hand, both the judges and the viewers — most of them farmers and shepherds — knew how to recognize a good performance. The best dogs’ working method matched fairly well with the recommendations for good shepherding made in the literature discussed above.

The Gentrification of Trialling

The Bala initiative was widely followed. Within a few years, associations were established that organized herding competitions in Wales and the border counties of England and Scotland, and by the end of the century many British regions had their own trials. Most events were initiated by gentry landowners, while some others were part of a dog or agricultural show. The bigger trials became yearly events, with spectator numbers in the hundreds or even thousands. The number of viewers at the first Bala trials was estimated at three hundred, some two thirds of them farmers and shepherds. The third edition had more than two thousand people watching, with police present to keep good order.34 The 1883 trials of the North-Western Counties Sheepdog Trials Association boasted more than four thousand visitors, the 1904 Longshaw trials seven thousand, and the 1910 Llangollen trials even eight thousand.35 Only the trials on the grounds of Alexandra Palace in London attracted disappointing numbers of visitors. Apparently, a reporter surmised, Londoners could not imagine the attractiveness of such an event.36

The customary number of sheep in a trial run was three. Swift mountain sheep continued to be preferred, also in lowland regions — a Welsh flock was transported to London especially for the Alexandra Palace trials. In the border counties, other hill sheep such as Cheviots and Scottish Blackfaces were deployed. The criterion was that trial sheep should be agile and fast, in order to pose a real challenge to the dog. Lowland sheep did not fit the bill, as they were heavier and slower. The second edition of the Bala trials set an example by having the dogs work three sheep picked from three separate flocks, which made it even more difficult to keep them together.37 On the other hand, the dogs’ work was made easier at most trials by releasing the triplets from a separate pen on the course, with the flocks from which they were drafted out of view. The number of competing dogs was typically between twenty and forty, but some had more than sixty. The beauty contest remained a regular part of the proceedings. The bigger trials soon became two-day events, with work starting early and continuing till dusk. A time limit for each run was introduced at the Garth trials of 1875 and this would become normal procedure at most trials hereafter.38 Besides the most important stake, open to all dogs, there might be separate stakes for local dogs, and sometimes for young dogs and young handlers.39 Remarkably, the North-Western Counties Trials Association initially had separate classes for bitches and dogs in all stakes. No reasons were given, but the division disappeared after a few years, arguably because there were indeed no reasons for it, other than the convention of gender segregation in sports.40

The course set-up showed considerable variation from event to event, but there was a common core to the trials’ format. They all ended with the penning exercise and began with the dog having to fetch the sheep, after their release at distances of about four hundred to eight hundred yards from the shepherd. Between start and finish the dogs had to drive the sheep to the shepherd, negotiating various obstacles along the way, such as flagpoles which the sheep had to be driven around, and gaps in hedges or fences they had to be driven through. Penning was often made more difficult by narrowing the openings between the hurdles. A novelty introduced in the 1890s was the Maltese cross, a contraption made of hurdles with two passages at a ninety-degree angle, which the sheep had to be driven through in either one or both directions.41 The 1880 Llangollen trials introduced a new task, the shed. With the shepherd’s assistance the dog had to separate three marked sheep from a flock of nine and pen them.42 In the 1900s, Scottish trials required the dogs to shed and control a single sheep.43 A special stake was added to the Llangollen trials of 1892, in which a team of two dogs had to bring two separately released lots of sheep together, shed three marked sheep, and then pen them all.44 The public much appreciated this brace competition and it was included in many trials.

It was not only the design of the trial course that evolved. Under the scrutiny of the judges, the dogs and shepherds’ behaviour also changed, developing into a pas de deux with a distinct choreography that became the hallmark of sophisticated herding. This fine adjustment of trialling conduct was by and large complete by the 1900s. The judges, mostly local farmers “who thoroughly understand shepherding”, soon began to deploy point systems and penalties to assess the quality of the performance of both shepherd and dog.45 There was little uniformity, however, with judges at different trials giving various points for the initial fetch of the sheep, the drive, and the pen, as well as for the shepherd’s command of the dog and the latter’s style of working.46 At many trials, speed was a guiding criterion for placing the winners, but the fastest worker did not automatically win: “superior style” might trump speed.47

The shepherd was permitted to assist the dog at the pen and the Maltese cross, yet after the first Bala trials pushing or even touching the sheep was no longer allowed. The Ulverston trials of 1880 introduced the rule that a shepherd would be disqualified if he touched a sheep.48 The shepherd’s latitude was restricted by assigning him a fixed space, which he was only allowed to leave to provide assistance at the cross and the pen.49 While the judges at the first Bala trials had tolerated biting, at the third edition they disqualified a dog for mauling a sheep.50 The North-Western Counties Sheepdog Trials Association, initiated in 1877, stated as one of its chief objectives “that of humanity, inducing gentle treatment of the sheep by the dog”, implying that biting was to be penalized by disqualification.51 All trial committees would adopt this rule, which may explain why the skill of catching and holding a sheep to enable the shepherd to inspect them was never demonstrated at the trials. While earlier and contemporary writers, as we saw above, considered catching to be part and parcel of the sheepdog’s work, the committees apparently did not deem it appropriate, at least not for public display.

An aspect of herding conduct that was more and more rebuked over the years was barking. It was already frowned upon at the first Bala trials, and three years later a bitch was said to display “veritable stupidity” because she “ran in, barked, and scattered the sheep”.52 At trials near Carlisle in 1885 the Field journalist noted that “by yelping and barking in a most furious manner”, a dog’s “chance of victory was extinguished”.53 The reporter of the 1895 West Riding trials regarded barking as “most unprofessional”, and by that time it had indeed become an anomaly; witness the comment that a “yelping dog” was a “somewhat rare competitor at trials of this kind”.54 The undesirability of a noisy performance had as a consequence that, besides catching a sheep, yet another aspect of practical shepherding deemed useful by agricultural writers was not demonstrated at the trials: the ability of a dog to bark on command.

The creeping and crouching movements that only some dogs had demonstrated in the early years of the trials soon became a standard part of good penning style.55 John Henry Walsh, editor of The Field and a leading authority on dogs, considered it a characteristic of the collie’s herding method to face the sheep, lie down, then take a few steps forward, lie down again, and so on, thus preventing his charges from breaking away while at the same time pushing them in the desired direction.56 By the 1890s, most dogs had mastered this technique: “Toss worked beautifully, crawling and creeping as required”, the chronicler of a Welsh trial noted in 1892.57 In 1897, Jack was even said to have “marred an excellent performance by refusing to crouch at the pen”.58 Furthermore, it was not mandatory for the dogs to exercise control with their ‘eye’, but it was certainly regarded as an asset. At a competition in 1908, the judge blamed the failure of many dogs to keep their sheep under control on their lack of “strong eye”.59

In the early years of the trials, quite a few dogs, in their first approach of the sheep, made a beeline towards them, often scattering them as a result: “Laddie was a complete failure, running into his sheep as if he meant having a chop”.60 Soon, however, the better dogs were praised for going around the sheep in a wide arc, ending up behind them.61 This wide approach was initially identified as the ‘run out’, and eventually as the ‘outrun’, as it is today.62

Not only the dogs were expected to avoid unnecessary noise, however. In the early years, the public chuckled at the shepherds’ hollering to direct and correct their dogs, but over the years loud shouting was increasingly disapproved of. Of the shepherds’ three means of communication, the whistle, arm gestures, and voice commands, the latter came to be considered the least stylish. In its report on a demonstration trial especially arranged for Queen Victoria in 1889, The Field noted: “The style in which Mr. Rowlands worked his colley demands special notice, and is worthy the emulation by every shepherd, especially as he gave instructions to his dog by signs and by whistle, without any shouting whatsoever”.63 Rowlands was not the first shepherd to cultivate this silent working style. William Wallace, a Northumberland shepherd, directed his dogs almost entirely by arm movements and whistling at the Hawick trials of 1883, and at the Kington trials of 1878 Mr. Powell drew the spectators’ attention by working “solely by the different notes sounded on the whistle”.64 Many shepherds would continue to use voice commands, probably because they simply could not do without them, but the best competitors avoided them, because a dog who “required too much shouting at” was not appreciated by the judges.65 In 1892, at a sheep-penning competition near Aberdeen — another novelty, in that the shepherd was not allowed to assist the dog — a special prize was awarded to the shepherd working most quietly.66 A Scottish trial in 1906 had a prize for the “dog working best to the call of the whistle alone”.67

Working quietly also meant that both shepherd and dog were expected to suppress all outward signs of excitement or impatience. In 1884, the “main excellence” of Thomas Telfer’s dog Speed was said to “lay in his gentleness and absence of all appearances of excitement while in view of the sheep, which he worked without fuss and noise”.68 At the 1893 Kilmarnock trials, a duo was praised because “neither dog nor man lost head or temper, and both seemed to understand each other. A good example of what a sheepdog, properly trained, can do”. In contrast, at the Llangollen trials of 1898, a dog was said to be “rather harshly worked, his handler becoming very excited”.69

By the 1890s, the shepherds who made a name for themselves all demonstrated this restrained and silent working style. Among them were trialling luminaries such as William Wallace, father and son Jonathan and George Barcroft, and James Scott. These handlers were veritable circuit-goers, demonstrating their skills throughout the country. They also played a prominent role in spreading the fame of the collie abroad. An English team including Jonathan Barcroft was invited to (and won) a sheepdog trial in Germany in 1897, with the emperor, Wilhelm II, among the spectators. Wallace, Jonathan Barcroft and others competed in Ireland in 1898, and in 1910 James Scott was one of three shepherds who, with six of their dogs, toured the USA to give demonstrations.70 As a result of the collie’s growing fame, hundreds of dogs found their way to buyers in the USA, Canada, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and many other countries over the course of the twentieth century. In Britain, prize-winning dogs became the foundational animals of the modern border collie population, their names figuring prominently in the pedigrees of today’s dogs.71

For the top handlers, trialling was a lucrative business. George Barcroft’s frequent trial winner Don, to give an example, was sold for eighty pounds in 1902 — some eight thousand pounds today.72 Trial winners customarily took home between five and fifteen pounds.73 In addition, gentry landowners regularly provided silver cups worth up to fifteen pounds.74 The Barcrofts’ star dog White Bob earned his owners more than seventy pounds in a single season, and George Barcroft’s total income from prizes and trophies was reported to have amounted to some 2,500 pounds.75

By the 1900s, trial dogs were still diverse in outward appearance, but less so than in the early years, when some dogs were of the bigger drover type, others of the smaller collie type, and still others something beardie-like in between. Shepherds with English drover dogs soon found out, however, that this type of competition was not for them. The drovers who competed at the Alexandra Palace trials in 1876 nearly all lost their sheep “over the hills and far away”, and at the 1880 edition a shepherd with a similar type of dog withdrew from the competition when he saw the course to be completed.76 At trials near Clapham in 1884, a drover described as a “bobtailed cur” was said to bark so much and drive so badly that he was called up “before he had an opportunity of further misbehaving himself”.77 As it turned out, the dogs whose behaviour did meet the competition requirements were mostly of the herding type Youatt had described as the Highland collie, and by the 1900s they had come to predominate at the trials. A few beardies or beardie crosses were still competitive in those years, but the type would gradually disappear.78

Whatever their looks, the dogs’ preferred herding behaviour was clearly defined by 1900, and so were the shepherd’s demeanour and interaction with his dog. In its first decades, I would suggest, trialling — a male-only sport in the nineteenth century — underwent a stylization that had clear overtones of Victorian middle class and genteel ideals of manliness.79 Appropriate manly behaviour was based on restraint and self-control and did not allow for outward displays of excitement, nor for raising one’s voice or wild gesticulation. Dominance should be embodied in and flow naturally from posture and gaze: the judges rewarded natural authority and quiet command, of the shepherd over the dog, and of the dog over the sheep. Thus, the improvement of shepherding, the stated objective of the genteel organizers of the trials, amounted to the shepherds and their dogs emulating the norms of conduct of their patrons. The remarkably formal attire of the shepherds at the trials, illustrated in the photo (fig. 6) below, supports this interpretation.

Fig. 6 George Barcroft (left) at the Wirral trials of 6 June 1892. The black-eared dog on the right is White Bob.

In The British Fancier, 10 June 1892 Courtesy of Shirley Duckworth and Judi Max .

Early Criticism

Given that the trials fine-tuned the performance of both shepherds and dogs, did sheep farmers and their patrons appreciate the changes as benefiting sheep management at the farm? One might think they did, considering the involvement of some of them in the trials as organizers and judges. As it turns out, however, The Field’s reports elicited negative readers’ reactions from the beginning. These would grow into a sustained undercurrent of critical comments, which, despite the trials’ success as sporting events, cast doubt on the supposition that they achieved their intended practical goal.

In 1875, two years after the competitions began, a sheep farmer from the English Midlands wrote a letter to The Field expressing his concern about the working style of the trial dogs. Which kind of dog was best suited for farm work depended entirely on the region, he contended. Agile collies might be useful on the open hills of Scotland and Wales, but he himself had no need for them. Shepherding in the Midlands was much easier, as pastures were enclosed and fairly small. Therefore, his shepherd worked with a big bitch who was “ancient, fat, and lazy”. It was “quite a treat”, he noted, “to see the mild and easy way she performs her work”. She was equally suitable for driving sheep from the market to the farm, as she made them “reach home quietly and safely, without being overdriven”. One of his other dogs, he added, was a collie, but he did not like the way she worked at all. She was “very active and quick, and when she starts to her work is gone like a bullet from a rifle, and at times makes me tremble, fearing she may drive the sheep over the fences or hurdles”. Generally speaking, he concluded, it was not the collie, but the “heavy, old-fashioned, bob-tailed English sheepdog”, who best suited Midland farmers.80

This comment echoes William Ellis’ opinion, expressed a century earlier, that in enclosed fields a lame shepherd and a lazy dog were the best flock attendants. In 1881, a commentator likewise remarked that in counties where “sheep are continually penned, there is little opportunity for the high training of the colley […] Shepherds in the close-folding districts train their dogs to the performance of a few simple duties, and that is all”.81 Rawdon Lee agreed: “The big, heavy sheep of the Sussex Downs, the Lincolnshire Wolds, and the Shropshire Pastures require little driving or looking after. Kept in inclosed land, they have not the opportunities afforded [to mountain sheep] of straying”.82

For these reasons, shepherds from the South Downs saw no point in participating in sheepdog trials. They deployed beardie-like dogs who, because of their unhurried style of working, were no match for the collies on the trial course. Neither a trial judge who travelled to the South Downs especially to instruct them how to work collies, nor demonstration trials by northern shepherds could convince them otherwise; the southern shepherds were perfectly happy with their dogs and remained uninterested in trialling. Attempts to organize trials in Kent failed for the same reason.83

Other critics contended that the trials insufficiently reflected the sheepdog’s work at the farm, even in the hill counties.84 After visiting the 1867 Alexandra Palace trials, Lord Arthur Cecil of Orchardmains, an acclaimed breeder of dogs, horses and cattle, expressed his dissatisfaction with the set-up of the trials course in The Field. Working three sheep, he commented, did not reflect a sheepdog’s daily routines. Such a small lot, terrified by the unfamiliar situation they were brought into, could only be expected to scatter in all directions, giving the dogs little chance to show their prowess. Furthermore, it was pointless to judge dogs on the basis of speed of working, as fast dogs merely ran the fat off the sheep.85 Other critics expressed similar concerns in these years, emphasizing that the dogs’ day-to-day tasks should be central to the competitions.86 The effectiveness of the competing dogs’ conduct was also questioned. For instance, in the 1890s several commentators remarked that the collies’ increasing tendency to drop when driving sheep was superfluous. It was more efficient if they stayed on their feet and just stopped when necessary.87

A fundamental critique was published in The Field’s section “The Farm” in 1896. Spectacular as the dogs’ performance might look, the comment went, “it is questionable whether these trials should not be abolished altogether”. They encouraged highland shepherds to devise intensive training programmes for their dogs, and their “proficiency in the art of drilling the sheepdog” irritated the flocks and ran counter to the flockmaster’s prime interest: a well-dispersed flock of quietly grazing sheep.88 A decade later, in the same section of The Field, another attack on the utility of the trials began by noting that there was “considerable discussion” about the pros and cons of field trials among northern flock-owners, the majority of whom “condemn them not only as valueless, but as being actually objectionable”. The author listed three major complaints. To begin with, the trials tested only few aspects of the dogs’ multifaceted work on the hills, and their training was focussed on these aspects to the extent that their general working ability was impaired. For instance, the crucially important task of gathering widely dispersed sheep was not included in the trials. On the hills, trial-trained dogs might even be inclined to bring the sheep to the shepherd in small lots instead of searching far and wide to collect them all. Furthermore, trial dogs were directed for an important part by gestures, a method that was useless in the misty weather common in the mountains. Finally, the intensive training for the trials might cause injuries to the sheep. Thus “the welfare of any portion of the flock is subordinated to mere fancy, and absolutely needless, and, as many suggest, valueless, methods of training”. Utility was all that mattered, and “we have it on the authority of experienced hill farmers and shepherds that the two are by no means synonymous”.89

The 1908 edition of The Book of the Farm, the standard manual of Victorian agriculture, commented on the trials in much the same way:

These trials are objected to by many sheep-farmers, on the grounds that the operations performed at the trials are not such as are met with in ordinary sheep-farming practices, and that a good deal of harm is inflicted upon considerable numbers of sheep by excessive driving in the process of training the dogs for the competitions.90

An insider’s commentary on the trials was included in a contribution to The Field from 1911, authored by Charles Brewster MacPherson, a Scottish landowner, sheep farmer, trial judge, and successful trialler. He described an experience with his prize-winning collies when they were gathering sheep on the hills. Intent on evading the dogs, the sheep deployed the tactic of hiding in dense juniper bushes on the hill slopes, lying on their stomachs, their heads down. Unable to see the sheep, the dogs were at a loss to how to get them out. The reason for their failure was clear, according to MacPherson: true to their trial-winning status, his dogs worked as quiet as a mouse, which in the situation at hand was utterly ineffective:

What use now the lightening drop, the artful creep, the stealthy approach, the once loudly applauded style? As, pouring with perspiration, I thrash the bushes with my stick, and waving my coat aloft, even imitate the barking of a dog myself, I utter aloud the wish, “My kingdom for a barking dog!”91

MacPherson’s frustrating experience was not unique. The difficulty of dealing with sheep hiding in the undergrowth was regularly encountered during trials in the hill counties, and it were particularly the top handlers’ silent dogs who were baffled by the sheep’s ploy.92 The organizing committee of the Llangollen trials therefore resorted to cutting the undergrowth on the course terrain.93 This led John Dickson, the Scottish poet and hill shepherd, to sneer that trial collies only performed well on a golf course.94

The International Sheepdog Society’s Reforms

The popularity of the trials did not suffer from these negative assessments of their practical usefulness. On the contrary, in the twentieth century they would grow into a worldwide phenomenon, with an increasing number of triallers without a farming background, and with more and more women contenders after the Second World War.95 Training sheepdogs and competing in trials provided “pretty amusement” to any dog lover, the editor of The Kennel wrote in 1903, and a special stake for “amateurs” was organized as early as 1891 as part of the Denbigh trials.96 The first training club for sheepdogs was founded in Haddington near Edinburgh in 1906 — the same year the International Sheepdog Society (ISDS) was established.97 Outside Britain, trials associations were established even in countries where sheep farming was a marginal economic activity, and over the course of the twentieth century several national associations joined the ISDS as associate members. While nineteenth-century Londoners had never warmed up to the trials, in the years around the Second World War thousands of people — some twenty thousand in 1949 — watched the sheepdog trials sponsored by The Daily Express in London Hyde Park. The public success of the competitions reached new heights with the BBC show One Man and his Dog, which has been on air since 1976. In Britain, the number of viewers peaked at eight million in 1981.98 Today, handlers from all over the world compete in the ISDS’s World Sheepdog Trials. The first edition, held in Bala in 2002, attracted eighteen thousand visitors.99

So it was not without reason that Eric Halsall, longtime ISDS director, trial judge and commentator of the BBC show, declared the border collie to be one of the “great success stories of British agriculture”, and it was doubtlessly the public appeal of the trials that contributed largely to this success.100 What Halsall also meant, was that the trials had shown to the world that the border collie was the proverbial sheepdog: it was the collie who made sheep farming possible even under the most difficult conditions, and there was no herding breed anywhere in the world that surpassed the collie in sagacity and efficiency. In Halsall’s words, the collie was “the best dog in the world for that purpose”.101 In the same vein, the ISDS boasted that Britain “is very much the ‘kennel of the world’ as far as the working sheepdog is concerned”.102

All this is not to say that the landowners and farmers’ criticism of the trials left them unaffected. It may safely be assumed that the changes in the trials’ design and judging discussed by Urdank were a response to the critiques. Within the ISDS, farmers and shepherds took the lead in organizing trials and the role of the landed gentry gradually waned. A more “workmanlike” approach came to prevail, Urdank argued.103 The quality of the work became central, and it was judged on the basis of an elaborate point system. Speed of working was considered less important, and the dogs’ ability to work effectively and independently gained prominence over ‘style’ and ‘command’. The Maltese cross disappeared, the entrance of the pen was made wider, and in the championship final round dogs were required to work two lots of ten sheep. The beauty contest was replaced by competitions for “type” and “condition”, but eventually these elements were abolished altogether.

In line with this, it can be added, the shepherds’ use of voice commands returned. The trend towards exercising extreme restraint in this regard was at its peak in the decades around 1900 but was ultimately reversed. With genteel influence declining, voice commands once again became a normal part of the shepherds’ communication with their dogs, and they still are today. Concomitantly, the use of arm signals waned, and judges no longer put a premium on silent communication.104

It should be noted, however, that Urdank’s analysis only pertains to the ISDS trials and that, initially, the society was ‘international’ merely in that it brought triallers from Scotland and England together. Wales joined in the society in 1922, Ireland in 1961, but other nations can only become associate members. Moreover, the society was never a governing body that set rules to the British trialling circuit as a whole. Different course designs are still in use at the hundreds of smaller trials held every year at regional and local level. Many of these competitions continue to work with small lots of sheep, and dogs may still have to negotiate the Maltese cross.105 Outside Britain, different models are also used. At the Australian national championship competition, for instance, dogs have to work three sheep. Even more importantly, even though the ISDS put more emphasis on efficiency and independence, the collies’ typical herding behaviour — the principal attraction of the trials for the spectators — has not changed fundamentally. If anything, selective breeding has fixed the dogs’ typical motor patterns, such as “eye-stalk” and “clapping” — the technical term for crouching — ever more firmly in their hard-wired behavioural repertoire.106 For trial dogs, working silently is still mandatory, and biting continues to be a capital offense.

Later Criticism

What did not change either, was the criticism of the trials’ purported practical usefulness. It continued unabated, despite the ISDS’s reforms, and it can still be heard today. In 1929 top handler James Scott deplored the fact that “it is rare one meets a farmer who will give his hearty support to sheepdog trials”, one of the complaints being that their training caused unnecessary worrying of the flock.107 Similarly, in 1982 Eric Halsall, commentator of the BBC shows, wrote that farmers were still unconvinced of the border collie’s superior herding qualities and did not think the extra time involved in giving a working collie the extra polish needed for the trials was worth the effort.108 In Herdwicks (2009), a history of one of the Lake District’s principal sheep breeds, Geoff Brown, longtime secretary of the Herdwick Sheep Breeders Association, pointed out that Lake District sheepdogs, called “Cumberland Curs”, differ from border collies in several respects. They are “generally much less biddable than the Collie”, who is selected for “obedience rather than for an instinctive and intelligent ability to seek and gather sheep which is the hallmark of the good fell dog”. Echoing MacPherson’s observations in The Field, he noted that work on the fells requires a dog who barks when the sheep go into hiding, for instance, on slopes with extensive bracken growth.109

In his Counting Sheep (2014) Philip Walling, a former Northumberland sheep farmer and writer, observed that the trial collie is not up to strenuous fell work.110 The trials require short bursts of energy, and selective breeding has turned trial collies into sprinters lacking the stamina for long hours of gathering widely dispersed fell sheep. Especially on hot days, they may run out of steam and get overheated. Additionally, they do not bark, which is an indispensable quality to retrieve sheep from their hiding places and keep them moving. Experienced hill shepherds, Walling noted, use powerful barking dogs who can work on their own, and they look down upon trial collies as prime donne who let you down when you need them most.111 Iris Combe, a breeder and writer on collies, likewise acknowledged that a strong, loose-eyed — i.e., without strong eye — and barking dog is better suited for hill work.112 Some hill shepherds even use dogs of the hunter type, who, rather than herding them, chase the sheep to get them moving.113

In interviews on the website Shepherds with Beardies, which promotes the modern version of the beardie as a better alternative for herding sheep, shepherds criticize the high-strung disposition of the collie: they never ‘turn-off’ when near the sheep. Beardies are loose-eyed, drive in drover-like fashion, bark and bite when necessary, and can catch a sheep. Some shepherds consider the collie’s dropping and crouching unnecessary antics and a waste of time. Beardies always work on their feet.114 The Welsh Sheepdog Society also promotes the reconstruction of a barking, loose-eyed dog working on his feet, as used by Welsh hill shepherds before the introduction of the collie.115

Despite the ban on biting at the trials, hill shepherds in the twentieth century have continued to use collies that may bite sheep and can catch them on command.116 Even some contemporary triallers acknowledge that work at the hill farm places different demands on the dogs than what is expected on the course, and that biting — often euphemistically referred to as “gripping” — may be condoned in practical shepherding. For instance, Viv Billingham, a sheep farmer and an accomplished trialler, wrote: “I fear that the greater the popularity of trialling, the more attributes the dog will lose. The hill man’s requirements in a dog, namely power and practical ability, will always be the same”. Therefore, according to Billingham, if a sheep turns on the dog, biting is excusable, and if a ewe needs treatment, it is helpful to have a dog who knows how to catch her.117 Reversely, both Billingham and trialler Donald McCaig noted that, when competing in sheepdog trials with a powerful and self-willed dog, it is hard to avoid disqualification if the sheep do not readily cooperate.118

According to the ISDS, improving the sheepdog is still the society’s objective today, because “without a good working dog the work of the shepherd, both on the hills and the lowlands would be impossible”.119 The irony is, however, that trial collies, precisely because of their specialization for the trials, have become less, not more suitable for hill shepherding. Nor can it be said that such collies are indispensable in the lowlands. Today, with almost universal enclosure of pasture areas, lowland sheep farmers, like the farmers from the Midlands and the South we encountered above, do not need a highly trained trial collie.

Many sheep farmers are even better off without a sheepdog, the Coppingers noted, because the costs of training and maintaining a herding dog rarely outweigh the benefits.120 On the European continent, for instance, various types of sheepdogs were used until the end of the nineteenth century, but most of the working varieties have disappeared since then.121 Continental sheep farmers now routinely manage their enclosed flocks without dogs. Even when sheep have to be relocated over long distances, herding dogs are not self-evidently indispensable. For thousands of years, and since long before specialized herding dogs were developed, shepherds in the southern mountain ranges of Europe and Asia have been moving huge numbers of sheep over hundreds of miles during the yearly transhumance. They did (and still do) use dogs, but these were of the livestock guardian type, meant to protect the sheep from predators.122 To be sure, the trials have given the collie worldwide renown, and shepherds who feel they need a sheepdog often consider the border collie an obvious choice, but whether they really need such a dog is a different matter.

Australian and New Zealand sheep farmers certainly regard herding dogs as indispensable. Their dogs descend from ancestors imported from the UK in the nineteenth century to drive the imperial herds of British cattle and sheep “shot round the world”, as Rebecca Woods put it.123 Their herding conduct differs from that of their forebears, though. Selective breeding and crossing with other breeds have turned them into strong and independent dogs, such as the kelpie, the Australian cattle dog, and the huntaway, who use their bodies and teeth to control sheep.124 The huntaway barks loudly and incessantly while working, and, like the kelpie, jumps on the sheep’s backs, for instance to push them through handling equipment. The Australian cattle dog is a ‘heeler’ who bites his charges at the hocks. British sheepdogs exported to South and North America in the nineteenth century underwent similar changes in their behavioural repertoire.125

In sum, the claim that herding sheepdogs are indispensable for sheep farming is an exaggeration, and this is all the more true for the view that the ISDS trial collie is the best dog in the world for the purpose. For practical farm work, many shepherds all over the world prefer a different kind of dog. The typical trial collie is first and foremost a dog for sports and entertainment.

The Sheep in the Equation: Lead or Drive?

Historical research is not meant to tell us what to do, but it can raise relevant questions about the present. If sheepdog trialling is intended for sports and entertainment, a pertinent question is whether it is acceptable, from an animal welfare perspective, to continue the tradition. Herding is based on the dog’s predatory instinct, with the sheep as prey. For a sheepdog, executing this behaviour is intrinsically rewarding; for sheep it is anything but.126 Even under the best of circumstances, with a well-trained dog and a thoughtfully designed course, there is no fun in trialling for sheep. At the very least, their involuntary participation annoys them, but things do not always go well and running in a trial can be agonizing.127

Furthermore, trials only show the tip of the iceberg. Collies need to be trained, and sheep serving as ‘training material’ are worse off than sheep in actual competitions. While their behaviour is partly hard-wired, dogs must learn to obey commands and interact with the shepherd. There is also a lot they have to unlearn, such as harassing and biting the sheep,128 and a dog may even turn out to be unsuitable for competitive trialling. The sheep bear the burden of everything inexperienced and unfit dogs do but ought not to during the training process. Today, moreover, many people aspiring to participate in trials have no farming background and may initially know little about shepherding, meaning that sheep also have to endure the training process of such novices. It is not the purpose of this paper to make an ethical assessment of whether or not all this should be condoned for mere entertainment purposes, yet the question is justified.

It might be countered that the real problem is with the trials in their present form. In order to really contribute to their stated purpose — the improvement of practical shepherding — they should be brought more into line with the daily routines at the farm. However, a closer alignment of the trials with actual shepherding practices, in Britain and beyond, would also call for a different type of dog. Further, sheep welfare will not improve by replacing the trial collies with dogs who, like some of the border collie’s foreign cousins, bark a lot, bite the sheep, and jump on their backs.

However this may be, the history of shepherding suggests an alternative solution. The worldwide reputation of the collie as a herding dog is an example of British exceptionalism that has gone global. For millennia, the world’s domestic sheep were not driven by dogs, but led by the shepherd. If sheepdogs were used at all, they were of the livestock guardian type.129 British shepherds deviated from this model, probably in the late Middle Ages, when they switched to a system of shepherding in which sheep were gathered and moved by driving dogs, with the shepherd walking behind the flock instead of in front. The explanation, already to be found in Caius’s description of the sheepdog from 1576, is well-known: the early extermination of the wolf in Britain enabled shepherds to pasture their sheep in open fields, where they could disperse widely without risk of predation, even if left unattended.130 One can see the rationale, in such a situation, of having a gathering dog to collect the sheep and to drive them in any desired direction.

Outside Britain, the older model of leading the sheep was maintained, and some of the British agricultural writers discussed above were remarkably positive about it. In his plea against too much ‘dogging’ of the sheep, Ellis approvingly quoted a French author saying that shepherds should be the sheep’s “Leaders and Guides” rather than their “Lords”.131 Youatt contrasted the peaceful way continental shepherds moved their flocks with the sometimes-brutal approach of English shepherds. Citing a work on Spanish Merinos, he wrote: “There is no driving of the flock; that is a practice entirely unknown; but the shepherd, when he wishes to remove his sheep, calls to him a tame wether accustomed to feed from his hands. The favourite, however distant, obeys his call, and the rest follow”.132 According to Henry Stephens, ewes with young lambs should not be driven at all. The shepherd should carry one of the lambs in his arms and have the ewes follow him.133

Fig. 7 A Dutch shepherd leading his flock.

Elias Stark, “Schaapskudde op de heide”, 1889, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

In her Shepherds of Britain (1911) Adelaide Gosset noted that, as an exception to the rule, shepherds of the Downs preferred to lead their flocks. This neatly explains why, as noted above, they were unimpressed by the collie’s working style and found no interest in the trials.134 Leading the sheep would remain an anomaly in Britain, but its advantages were occasionally reiterated — for instance by that maverick of British agriculture, Allen Fraser, in his Animal Breeding Heresies (1960). In the Middle East, he wrote, shepherding was “so much more delicate, more gentle and I am certain of it, biologically more sound. The sheep were never driven. They were led”.135 This different role of the shepherd had a different attitude towards the sheep as a corollary. Fraser continued by referring to the biblical metaphor of the Lord as the good shepherd: “the sheep hear his voice; and he calleth his own sheep by name, and leadeth them out […] he goeth before them, and the sheep follow him, for they know his voice” (John 10: 3–5). It is precisely because of their trustfulness and compliance that sheep epitomize the faithful believer in Judeo-Christianity.

The Field’s reports on the sheepdog trials present a starkly contrasting metaphorical image of sheep: that of icons of stupidity. They are called stupid, countless times, for not cooperating or actively resisting: “he had stupid sheep, and failed to pen”; “a trio of horned imbeciles”; “the pig easily holds the record of crass stupidity [yet sheepdog trials] reveal the sheep as it really is, the embodiment of unadulterated, maddening perversity in a concentrated form that is unapproachable by any other animal”.136 Not surprisingly, the commentators’ qualifications of the dogs’ behaviour were exactly opposite: intelligent, sagacious, patient, tactful, and obedient. On the trial course, the sheep could never win: if they cooperated, the dog won; if they didn’t, they were stupid.137

This stereotype of stupidity reflects a vision of shepherding based on dominance and control rather than trust and cooperation, reducing sheep to subaltern creatures whose lack of rationality justifies their subjugation. As recent studies confirm, however, sheep are not stupid. They are social animals that form long-lasting bonds with their offspring and with each other.138 Sheep recognize flock members and humans individually, even from photographs, and can read facial expressions.139 Their safety and well-being are in the group, and their flocking behaviour is a manifestation of their social intelligence and collective memory, not of lack of individuality.140 Calling sheep stupid, Sarah Franklin observed, may derive from the Western inclination to see intelligence and individualism as inextricably linked. In China, where “conformity is a competitive social skill”, sheep are considered highly intelligent animals.141

By virtue of their flocking instinct, sheep are trainable as a group. A poignant example: at the slaughterhouse a flock can be induced to calmly follow a trained sheep, which prevents them from panicking when having to enter the facility.142 In shepherding, it is not only the shepherd and the dog who communicate: it is not uncommon for sheep to respond to a command given to the dog.143 Scandinavian farmers have an age-old tradition of calling their cows home for milking (“kulning”), and sheep can likewise be called to come to the shepherd.144 Establishing trust is crucial for sheep to come when called, and if they are willing to come, they can also be led.

I can adduce my own experience in shepherding without a dog as an illustration. For more than twenty-five years, my partner and I have had a flock of some twenty Clun Forest sheep, a Shropshire breed with a reputation for skittishness. In the first weeks after we bought them, their sole intent seemed to be to stay as far away from us as possible. This changed when we started feeding them, and after some time, they were willing to come when we called them to the feeding trough. The next step was that they would follow us to the trough in an adjacent pasture. Eventually, they were also prepared to follow us to the shed and to a new pasture further down the road. It took more time (and patience on our part) for them to decide that the trailer means good news — a fresh field. They now enter it of their own accord. They are still easily spooked, for instance by strangers or tractors, and, once in a while, a ewe jumps the fence and dashes off. To retrieve her, we walk the flock towards her, and she will gladly join it to return home. We have never needed to repeat the training process with newcomers or lambs. Older ewes who know the routines teach them by example how things work.

Admittedly, all this is more difficult to achieve on Highland farms, where sheep are often left to their own devices for most of the year, yet even hill sheep come to the shepherd for winter feeding, and they can also be called.145 On the European continent, after a steep decline in the twentieth century, shepherding is being reintroduced on a modest scale, mainly for conservation, cultural heritage, and education purposes. Newfangled shepherds often know no better than to drive their sheep with border collies, but others have restored the traditional practice of leading them. Still, they often need dogs that flank the moving flock or act as a living fence to keep the grazing sheep out of crop fields and other no-go areas. Trials and demonstrations are being organized to enhance their working abilities.146 From a sheep welfare perspective, shepherding with these loose-eyed dogs is not always an improvement, as some types can be harsh on straying sheep. In my opinion, their barking (except perhaps on command) and biting should best be penalized by trial judges, as in the case of the border collie trials.

It seems likely the time is near when using animals against their will and at the expense of their welfare will no longer be considered acceptable for entertainment purposes. If there is to be a future for sheepdog trials, it seems to lie in a model that serves to improve practical sheep management and at the same time meets sheep welfare requirements. This means that sheep should be led rather than driven, with trust and cooperation as guiding principles rather than dominance and coercion. The days of the trial collie would then be over. For practical shepherding, in cases where the help of dogs is deemed indispensable, sheepdogs who function as the eyes in the shepherd’s back and do not worry the sheep hold out the best promise of sheep-friendly shepherding. The collies surely won’t mind being replaced. There is no lack of other sportive opportunities for them to have fun.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the many shepherds who shared their thoughts about styles of shepherding with me. Thanks also to Margaret Derry, Gareth Enticott (who is writing a book on the history of the New Zealand huntaway), and Elian Hattinga for their encouragement and suggestions. Two anonymous reviewers provided perceptive criticism that helped me to improve the paper. Sheep do have opinions (Despret), and my own sheep’s eagerness to share them, across the species barrier, provided the incentive for writing this paper.

Notes

Coppinger and Coppinger, Dogs, 189.

Hogg, The Shepherd’s Calendar, 308–9.

See “What We Do”, International Sheepdog Society, accessed 16 July 2025, https://www.ISDS.org.uk/the-ISDS/what-we-do/.

Halsall, Sheepdog Trials, 36.

Worboys, Strange, and Pemberton, The Invention, 213–18; Derry, Bred for Perfection, 67–102.

Urdank, “Rationalisation”, 78. Details on some early trials are provided at the websites “Shepherds with Beardies” (now defunct, but archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20160423005146/http:/shepherdswithbeardies.com/index.html) and The Border Collie Museum (www.bordercolliemuseum.org), and in Wentworth-Day, The Wisest Dogs. There is a plethora of books on the border collie, and many contain some (and mostly the same) historical information, usually without references.

The Field (henceforth cited as Field) is still in print as a monthly magazine. Its publications from 1853 until 1911 are digitally retrievable from the British Newspaper Archive of the British Library. I have used this digital repository as my primary source, using “sheepdog”, “sheep dog” and “trials” as keywords to retrieve the journal’s reports on the trials and other potentially relevant articles. The Field reported on the major trials; there were many local ones that, if mentioned, were merely announced. Some other periodicals, such as the British Fancier and the Ramsbottom Observer, also reported on the trials, but more incidentally; The Field had the widest coverage.

Derry, Bred for Perfection, 48–102; Ritvo, The Animal Estate, 82–115, and The Platypus, 104–120; Worboys, Strange, and Pemberton, The Invention. For farm animals more generally, see for instance Trow-Smith, A History.

The descriptions of drover and shepherd dogs in this paragraph are based on Beilby and Bewick, A General History; Edwards, Cynographia; Taplin, The Sportsman’s Cabinet; Bingley and Howett, Memoirs; Brown, Biographical Sketches; Smith, The Natural History; Youatt, The Dog; Martin, The History; Meyrick, House Dogs; Stonehenge, The Dogs; Dalziel, British Dogs; Shaw, The Illustrated Book; Lee, A History; Leighton, The New Book.

Hancock, Dogs of the Shepherds, 10–14, 90.

Leighton (The New Book, 102) described the type as the “Scottish bearded” in 1907. See also Hancock, Dogs of the Shepherds, 90–92, and the now-defunct website “Shepherds with Beardies”, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20160423005146/http:/shepherdswithbeardies.com/index.html. The bearded collie as a recognized show breed did not emerge until the 1950s.

Coppinger and Coppinger, Dogs, 189–224. For a history of herding behaviour, and descriptions of the communication between shepherd and dog, see Westling, “Zoosemiotics”, and Savalois, “Teaching the Dog”.

Caius, Of Englishe Dogges, 24. Another early source is Mascall (The First Book, 231), who wrote that a sheepdog should bark on command, never chase the sheep, and stop running when told.

Ellis, A Compleat System, 1–34.

Beilby and Bewick, A General History, 284–285; Edwards, Cynographia, 64–65.

Little, Practical Observations, 80.

Youatt, The Dog, 61.

St. John, Short Sketches, 110.

McCulloch, Sheep Dogs, 17–18. For a similar opinion, see Holmes, The Farmer’s Dog, 17–18.

Hogg, The Shepherd’s Calendar, 311–312.

Brown, Biographical Sketches, 131.

Unrecorded trials were claimed to have been organized in Kirkby Stephen in Cumbria since the late 1850s: “Kirkby Stephen Dog Show and Sheepdog Trials”, Field, 4 September 1880, 369–370. Trialling in Australia started in the 1860s; see Wayne McMillan, “Historical Australian Sheepdog Trials”, Australian Working Stock Dog Magazine no. 16 (August 2021), 36–41, https://issuu.com/awsdm/docs/awsdm_june_2021/s/13169208.

Lee, A History, 102.

Urdank, “The Rationalisation”.

Worboys, Strange and Pemberton, The Invention, 79–83. An announcement of the Bala trials mentioned that this “novelty” was to be organized by the same committee that was engaged in setting up a gun dog trial in the area. The main organizer, Richard John Lloyd Price Esq., was a well-known figure in both the dog fancy and gun dog trialling. See R.J. Lloyd Price, “Sheepdogs at the Rwilas Field Trials”, Field, July 6, 1873, 17; Halsall, Sheepdog Trials, 25–26.

“Sheepdog Trials at Ulverston”, Field, 9 October 1880, 558.

Worboys, Strange and Pemberton, The Invention, 79–83.

A bone of contention, for instance, was the cross of the collie with the Gordon Setter, which fancy breeders used to add brilliance to the coat but was said to impair working ability. See Stonehenge, “The Colley and other Sheepdogs”, Field, 11 August 1877, 161–162; Shaw, The Illustrated Book, 73–82; Worboys, Strange and Pemberton, The Invention, 213–218.

Lee, A History, iv.

“Sheep Dog Field Trials at Bala. Thursday, Oct 9”, Field, October 19, 1873, 390; all quotations in my description of the event derive from this source.

“National Sheep Dog Trials”, Field, 17 October 1874, 404.

The same applied to The Field’s reporter. His somewhat sensationalist account differs from later reports, which were written more matter-of-factly.

“National Sheepdog Trials at Bala. Another Account”, Field, 23 October 1875, 441.

“North-Western Counties Sheepdog Trials”, Field, 1 September 1883, 312–13; “Longshaw Sheepdog Trials”, Field, 24 September 1904, 545; “Vale of Llangollen Sheepdog Trials”, Field, 13 August 1910, 322.

“Collie Trials at the Alexandra Palace”, The Daily News, 30 June 1876, 5.

“National Sheepdog Trials”, Field, 17 October 1874, 404.

“The Garth Colley Trials”, Field, 14 August 1875, 197.

See for instance, “Grand Trial of Sheep Dogs”, Field, 16 September 1876, n.p.

“North-Western Counties Sheepdog Trials”, Field, 6 September 1879, 319, and 1 September 1883, 312–13.

See, for instance, “Sheepdog Trials at Tring”, Field, 7 August 1897, 211.

“The Llangollen Sheepdog Trials”, Field, 16 October 1880, 584.

See, for instance, “Sheepdog Trials at Gullane”, Field, 8 September 1906, 434.

“A Sheep Dog Trial in Wales”, Field, 13 August 1892, 254.

“North-Western Counties Sheepdog Trials”, Field, 22 September 1888, 423.

For examples, see the 1892 trials in Wirral, Cheshire, discussed in Urdank, “The Rationalisation”, 71, and “Sheepdog Trials in Scotland”, Field, 29 September 1906, 550. See also Jones, Sheep-dog Trials.

See for instance “The Sheepdog Trials at the Alexandra Palace”, Field, 8 July 1876, 45.