Avi

Representation and Reality of Barcelona’s Iconic Zoo Elephant (ca. 1873–1914)

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.19872

Keywords: elephant, captivity, animal biography, animal agency, Barcelona Zoo, anthropomorphism

Email: oliver.hochadel@imf.csic.es

Humanimalia 16.1 (Winter 2025)

Abstract

At the same this article tries to reconstruct real-life experiences of Avi’s twenty-two years of captivity in the Barcelona Zoo. To reconstruct the (seemingly inaccessible) experiences of a long-dead animal represents an enormous methodological challenge that requires a constant reflection on the limitations of this approach. Reading the wealth of sources against the grain, it seems possible to identify some “reality fragments” and to show how Avi resisted or adapted to his situation in peculiar ways. Furthermore, zoo biologists, ethologists and elephant keepers have been consulted in order to apply their knowledge and sensibilities to the material, including Avi’s preserved skeleton.

Avi’s Agony — The Death of a Celebrity

On 1 May 1914, around 5 pm, Avi, the famous elephant of the Barcelona Zoo, collapsed in his enclosure and died. A week prior, the pachyderm had suffered an injury from the iron door of his enclosure to his left front leg. The ensuing infection proved fatal.1 For twenty-two years prior, the citizens of Barcelona had flocked to his enclosure to see the antics of the Asian elephant and now they were in shock. His sudden death reverberated strongly in the Catalan media, Avi made front-page news.2 The “obituaries” all told the story of Avi, his biography in a sense, some in a more serious, concerned tone, others tongue-in-cheek, ironic, or even with funny poems.3 The journalists agreed on how immensely popular the elephant had been. They pointed out Avi’s peculiar personality, his special relationship with children, and how the zoo visitors constantly fed him buns.

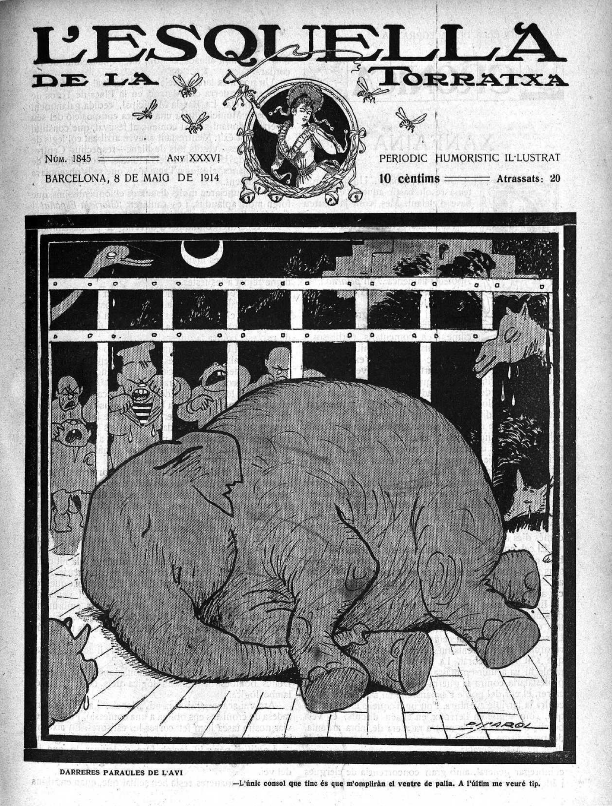

For two decades Avi had been a popular character for caricatures of all sorts, and the weekly L’Esquella de la Torratxa did not miss out on this last occasion either. In the sketch “Avi’s last words”, the elephant is stretched out dead in his paddock (fig. 1). Both humans (beyond the fence) and four different animals (inside the paddock) are bawling their eyes out. The caption reads: “My only consolation is that they will fill my belly with straw. At last, I will be full.”4 And not starving any more, the readers would add in their heads. Avi was fully aware that he will be taxidermized after his death, the caricaturist joked. So even given the sad news, the media machinery hammered on, entertaining their audience.

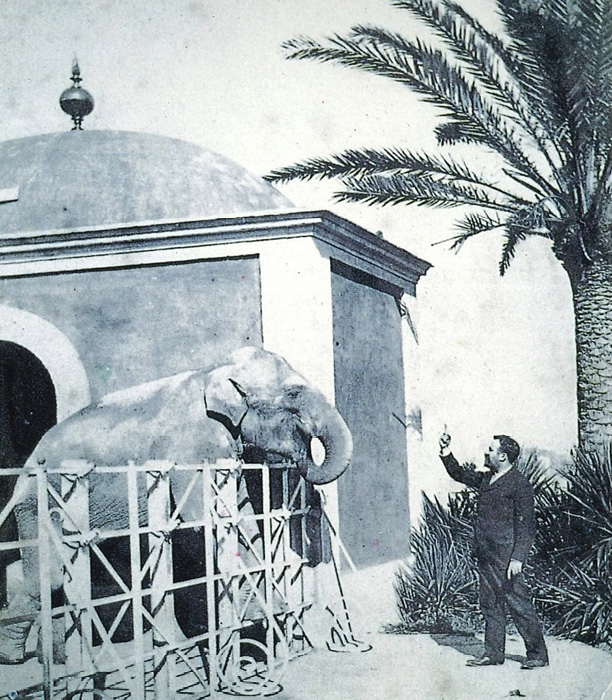

Avi did not only feature in numerous caricatures; he was also the most photographed animal in Catalonia during his residency at the zoo. Yet while virtually all these photos show a “happy” elephant interacting jovially with the visitors, there is one gruesome photo of the dead Avi (fig. 2). It was taken by the well-known photographer Frederic Ballell, who was probably called expressly to the zoo to document the sad occurrence. The elephant lies in his paddock (just like in the caricature) while a keeper moves his lifeless trunk, which was touched by so many Barcelonese. To the right, two men (cut off by the picture frame, hence hard to identify) are contemplating the scene. There seems to be a sort of make-shift canopy put up inside the paddock, likely to protect the suffering pachyderm from the sun.5 This photo — inscribed on the back with the words “L’Avi agonitzant” (Agonizing Avi) — conveys the drama of an intense but futile struggle for his life. We also see that the elephant was old and in a bad physical state: already emaciated with no fat pads, the jaw caved in, and the hip bones sticking out. The caricature, however, shows a healthy and well-fed elephant, rather sleeping than dead.

Fig. 1 “Avi’s last words.”

L’Esquella de la Torratxa, 8 May 1914, 305.

Biblioteca de Catalunya.

Avi and Avi — the Mediatic and the “Real” Elephant

The stark contrast between the caricature of L’Esquella de la Torratxa and the photo of Ballell epitomizes the topic of this article, the tension between the medially constructed Avi and the real-life experiences of the elephant in the Barcelona Zoo.6 Avi’s public persona is first and foremost a patchwork of the cultural representations of the elephant. He was the protagonist of hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles and featured in a variety of visual media: caricatures, drawings, postcards, photographs, and a biography in comic form, the auca, tracing his journey from the “Indian jungle” to the European metropolis. Avi’s name recognition in the public sphere turned him into a useful reference for political and social commentary in the local press. The appropriation went as far as “naturalizing” him as a Catalan citizen.

Fig. 2 Agonizing Avi.

Frederic Ballell, Arxiu fotogràfic de Barcelona, bcn001796.

In this sense Avi provides a well-illustrated example of “the development of the ‘animal entertainment’ industry, allowing the legitimization of captive institutions as places of harmonious human-animal relationships,” to quote from John Simons’s biography of Obaysch (1849–1878), the famous hippopotamus of the London Zoo, building on the argument of Susan Nance in her work on circus elephants.7

This article will go beyond the analysis of the cultural representations of Avi, marked by anthropomorphism and the imperative to entertain. Yet how may we reconstruct the seemingly inaccessible experiences of a long-dead animal? Is this possible at all? Éric Baratay and others have proposed a new methodology to write animal biographies. This article will test this recent approach in human-animal studies in order to gauge their potential and confront their challenges.8 The inherent limitations of animal biography need to be kept in mind.9

This methodology suggests reading the historical sources against the grain and at the same time to initiate an interdisciplinary dialogue with zoo biologists, ethologists and other experts of animal life. In this way, through a process of reiterations and approximations, historians might come closer to the experiences of the captive creature. In reconstructing the life of zoo animals, we have to rely on sources that are deeply shaped by the logic of the media and its local context. Not only are we “seeing” Avi through the lens of humans — the newspapers and other sources tended to present or even invent “coherent” stories, aiming to highlight the extraordinary and entertaining aspects of animal behaviour while suppressing, consciously or not, problematic aspects such as violence against the animal. In trying to reconstruct the experiences of an historic animal and understand its behaviour, we rely on sources meant to entertain and to fashion Avi into a hilarious, loveable, and exotic creature marked by traditional stereotypes about elephants.

As this article argues, there can be no straight line drawn between “merely” cultural representations and traces of the “real” Avi as they are inextricably mashed up. In talking about the elephant Ned/Tusko (ca. 1892–1933), Rothfels formulated this problem as a productive paradox: “The stories of Ned are not Ned, but they help explain much of what happened to him and help us better understand the history of how we have thought about elephants.”10 Yet still, the extraordinary wealth and diversity of sources on Avi provides an opportunity to identify “reality fragments”. For example, did he resist the way he was treated, and if so, how?

Methodologically, this requires a double approach: first, a thorough contextualization of the sources (Catalan history, local municipal politics, but also zoo and circus history) and second, the consultation of animal experts. In this case I conducted interviews with the elephant keepers and the veterinarian of the Barcelona Zoo as well as with the curator of mammalogy of the municipal natural history museum. We talked about the fundamental changes in elephant keeping and what information we may glean from Avi’s skeleton. The ethologist Franziska Hörner (University of Wuppertal, Germany) analysed the visual representations of Avi, in particular the large number of postcards, to ascertain his physical state and how this changed in the course of his time at the zoo.

In the last two decades or so, a number of publications have explored the lives of elephants in zoos and circuses, generally focusing on the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The works of Susan Nance and Nigel Rothfels might be the most significant ones.11 Yet most of this literature focuses on cases in Great Britain and the US, some valuable exceptions notwithstanding.12 This article argues that we need to enlarge our perspective to include many more cases from the “periphery”, outside the Anglo-American context.

Yet what could be learned from the case of Avi, and a seemingly insignificant zoo in Spain? In his monumental, 624-page Histoire des ménageries from 1912, Gustave Loisel (considered to be the first zoo historian) dedicated exactly one sentence to the Barcelona Zoo, concluding that “this menagerie is of no interest whatsoever”.13

In recent years, the urban history of the European “periphery” has been entirely re-evaluated, stressing its creative adaptation of metropolitan models and the “multitude of modernities”.14 In the early twentieth century, non-European zoos such as the Jardín Zoológico de Buenos Aires were hailed as exemplary.15 In our case, it is precisely the specificity (locality) of the Catalan example that constitutes its historiographical value. The political and social tensions of Barcelona around 1900, which evolved around violent class conflicts and the emerging Catalan nationalism, significantly shaped the construction of Avi’s mediatic persona. The idiosyncratic character of Catalonia’s public sphere (and the subordinate importance of the colonial dimension) contrast strongly with the biographies of zoo and circus elephants from London or New York. The potential of this case “from the margins” is further increased by the extraordinary richness and diversity of sources: the large number of caricatures, an unprecedented production of postcards featuring one single animal, a specific Catalan medium, the auca, as well as the post-mortem career of Avi as a museum object. This abundance of sources, in turn, facilitates the interdisciplinary dialogue with the aforementioned animal experts.

In this sense, this article also aims to contribute to the study of animal celebrity.16 Already in his lifetime, Avi was described as the undisputed star of the Barcelona Zoo. Yet, unlike many of the famous animals of the nineteenth century, such as the elephant Jumbo, Avi is a local celebrity, basically restricted to Catalonia — with some projection in the rest of Spain.17 As we shall see, this boundedness means that Avi’s appropriation played out in a way that made it incommensurable to international spread. This article thus highlights the need for more nuanced elephant biographies that go well beyond the metropolitan contexts that may have obscured their considerable variety. Cases such as Avi’s should help to relegate the category of “mere peripheral cases” to the moth-box of animal history. As Marianna Szczygielska puts it: “Capturing the animal’s individuality requires situating them as an actor or agent within the historical, social, and political reality they are or were embedded in”.18

This article has five major sections, each dedicated to a different group of sources: the press reports (including the caricatures), the auca, the postcards, the elephant house (the reconstruction of his small paddock with a sort of orientalist tower), and Avi’s mortal remains, the skeleton. In each part, we will contrast the cultural representations of Avi with the experiences of the “real” Avi to piece together the story of his life, as fragmentary as this may turn out to be. As “real” is potentially a problematic term, we will rather use the terms “corporeal”.

Articles on Avi — Between Appropriation and Agency

This section analyses the media coverage of Avi in (mostly) Catalan newspapers, magazines, and journals. Nearly all the basic information we have about Avi is based on this large number of articles and caricatures. Consequently, the conflicting biographical information as well as considerable lacunae with regards to our knowledge of the elephant’s life were also shaped by the media of the time. This focus on the press coverage brings to the fore how Avi was increasingly appropriated by the Catalan public sphere. At the same time, the sheer mass and diversity of these printed sources also allow for a reading against the grain in order to come closer to the corporeal Avi.

Fig. 3 The elephant with his owner Martí-Codolar at the Granja Vella.

Museu Martí-Codolar.

It was Francesc Darder (1851–1918) who travelled to Genova in 1881 or 1882 to pick up Avi and bring him to Catalonia.19 At the time, Darder, trained as a veterinarian, was a trader in natural history and the animal caretaker of Lluís Martí-Codolar (1843-1915).20 The Catalan banker owned a large estate with a private menagerie called the “Granja Vella” (Old Farm) in the village of Horta, at the time still outside the city limits of Barcelona (fig. 3).21 When Martí-Codolar went bankrupt in 1892, he sold his collection of 160 animals, including Avi, to the City of Barcelona. This collection formed the nucleus of the municipal zoo in the central Parc de la Ciutadella founded that same year. Darder became its first director and the zoo itself formed part of the municipal natural history museum (Museo Martorell) which was governed by the Junta de Ciencias Naturales (Board of Natural Sciences).22

There are many things we do not know about Avi: the exact circumstances of his purchase in Genova, such as price and seller; whether he was an elephant from India or another region of Southeast Asia; his exact age. A visitor of the Granja Vella in 1884 stated that he was six years old (i.e., born around 1878), Darder in 1893 appraised him as a twenty year old (i.e., born in 1873), and when Avi died in 1914, a newspaper referred to him as a forty year old (i.e., born in 1874).23

How Avi (Catalan for grandfather) got his name is not clear either.24 The few times he was mentioned in the press between 1881 and 1892, while in the private menagerie of the Granja Vella, he was not referred to by name.25 At the beginning of his time in the Barcelona Zoo, i.e., from Autumn 1892, he was called “el elefante del Parque”. According to the main narrative in posterior histories of the zoo, his original name was Baby. Yet because the Catalans found it hard to pronounce this word, he became the toothless grandfather.26 Avi had no tusks at the time. Darder himself still called the elephant “Bowi” in early 1893, which could refer to Bobby; a magazine article gave “Toby” as the original name.27 It seems that the magazine L’Esquella de la Torratxa named the elephant Avi in 1895/96.28 This mediatic baptism may be understood as the first crucial step of the transformation of the elephant from an “exotic” animal into a “citizen” of Barcelona.

The central mechanism of Avi’s cultural appropriation was based on two interrelated practices: the direct contact of zoo visitors with the elephant and its rich coverage by the Catalan press. Until 1927, the Barcelona Zoo was not fenced in, and no entry fee was charged.29 In other words, anyone could visit Avi during the opening hours of the Parc de la Ciutadella, which were generally during daytime. On numerous occasions, Avi grabbed the hats of visitors and munched them, adding to the spectacle of buns and apples being thrown at him.30 A recurring figure in the press coverage was that of the evil-minded visitor. These articles generally followed a basic narrative: be it out of curiosity or sheer malice, a man (yes, always a man) would take advantage of Avi’s habit to gorge himself on the food provided by the onlookers. The baddie would hand him a burning cigarette, a piece of broken glass, or a needle hidden within a bun. Zoo archives around the world testify to how widespread this kind of devious behaviour was. Yet the Barcelona elephant was not constructed as a helpless victim of the malicious visitors. Avi, always attentive, would see through the ruse and not swallow the dangerous item handed to him. Instead, he would spray the villain with water.31

These incidents coalesced into a central feature of Avi’s public persona: his “sense of justice”. One of the newspaper articles was even explicitly entitled “Justicia elefantisiaca”.32 The idea that an elephant “forgot neither a good deed nor an injustice” was deeply rooted in the Western imagination and dates back at least to the eighteenth century.33

All the elements mentioned so far were typical of a zoo elephant around 1900: the enormous popularity of the pachyderm, in particular with children, the constant attempts of visitors to touch the trunk, and the villains who tried to hurt the elephant by feeding him dangerous objects. There were numerous parallels, for example, between Avi and Maharajah, the famous Manchester elephant (1864-1882),34 and Gunda from the New York Zoo (d. 1915).35

However, each local context conditioned the cultural appropriation of an elephant. In the following, we will situate Avi within the specific milieu of Barcelona and Catalonia around 1900. Avi’s zoo years (1892-1914) coincide with an era of enormous social tensions in Barcelona, Catalonia, and Spain, which were repeatedly marked by political violence. In Barcelona they found their bloody climax in July 1909 in the so-called Setmana Tràgica (Tragic Week), an uprising of the lower classes that was brutally suppressed by the military.36 The time around 1900 was also the period of the rise of political Catalanism, in particular since the sweeping triumph of the Lliga regionalista in the elections of 1901 and in 1905 on the municipal level in Barcelona opened a second political fault line between the Catalan bourgeoisie and the central state in Madrid.

The popular magazines L’Esquella de la Torratxa, La Campana de Gracia, and ¡Cu-Cut! published a considerable number of articles and/or caricatures of Avi during his residency at the zoo.37 Initially, that is to say in the 1890s, these caricatures dealt with topics related to the zoo and its humorous potential, in particular through the use of anthropomorphism. Yet later on, the focus of these articles and caricatures shifted to local politics.

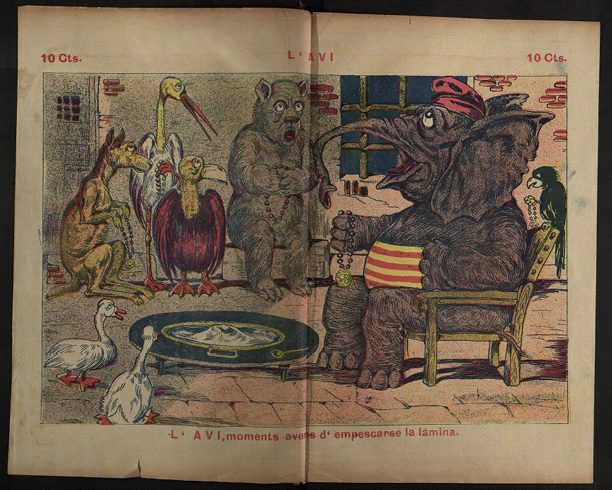

Avi’s “name recognition” was so potent that even a political satirical magazine was named after him, L’Avi. Setmanari satirich, which appeared between 1906 and 1908. The title head featured an elephant sitting at a writer’s desk, blowing sheets of paper with its trunk. The sense of justice attributed to Avi led him into the turbulent realm of Spanish politics. In a double-page coloured cartoon, the elephant sat in prison with the Catalan flag draped around his waist.38 Avi had left the zoo’s enclosure only to promptly end up behind bars again, the joke went (fig. 4).

It was mainly the republican and anti-clerical press that took advantage of the elephant’s notoriety and powerful image. Apart from the weekly L’Esquella de la Torratxa, there was also the daily El Diluvio, whose editorial line was highly critical of the City Council and, by extension, the municipal zoo and Darder. Avi often represented a critical citizen of Barcelona: democratically minded and keeping an eye on the powerful. Because of his size and strength, social hierarchies did not intimidate him. The connection between the zoo elephant and the political debate was therefore not arbitrary, as his incorruptible sense of justice, as well as his intelligence (he did not fall for attempts to deceive) made him an ideal mouthpiece for social critique.

From early on El Diluvio took a kind of protective attitude towards the elephant. The newspaper would not only point the finger at evil-minded visitors but also lambast the zoo for insufficient care, such as inadequate housing and lack of food.39 Critical of the establishment and its representatives, such as Darder, we might even interpret this attitude as treating the elephant as a subaltern subject that needed a strong public voice. In this sense, the elephant was integrated into the middle and lower classes of Barcelona, as El Diluvio saw itself as their public representative.40

Fig. 4 Avi as a Catalan nationalist in prison.

L’Avi. Setmanari satirich, no. 7/1906, Biblioteca de Catalunya.

One dimension that was rather absent in the cultural appropriation of Avi was colonialism. Unlike Great Britain and, later, Germany, Spain did not rule over any areas where elephants were indigenous. In the eighteenth century, some of the elephants for the court in Madrid came through the Philippines. Around 1900, the Spanish Empire was in rapid decline, having lost its last major colonies, the Philippines and Cuba in 1898. The auca to be discussed below imagined an Italian animal dealer to have brought Avi to Europe from British India. Therefore, an appropriation of zoo elephants as colonial trophies would not have worked like in other European imperial powers.41 Rather, the public figure of Avi was embroiled in the realm of local politics.

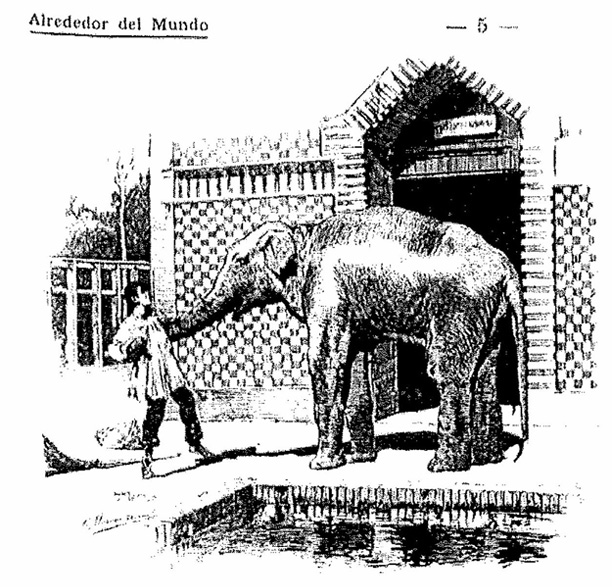

Having described the varied appropriations of Avi in the Catalan public sphere, we shall now screen the same sources (the press coverage) for instances in which we might catch a glimpse of the corporeal Avi. For example, did he resist the way he was treated? A rich source in this respect is an article entitled “El ‘Avi’ de Barcelona. Un elefante original” from the magazine Alrededor del Mundo. It was published on 9 June 1899 as the first article in the first issue of the journal. Alrededor del Mundo had its seat in Madrid but dedicated two entire pages to an elephant from Barcelona. Furthermore, it featured two drawings of Avi: one depicted the feeding practice of the visitors, the other showed Avi grabbing a keeper with his trunk. We may conclude that the publishers of Alrededor del Mundo thought such an extra expense would be worthwhile and impress their first readers (who might had heard about Avi and wanted to know more). Avi was portrayed as a sympathetic but headstrong creature who quickly saw through people’s intentions. He was also a “practical elephant,” having been raised in Catalonia. This may be read as an ironic allusion to the business acumen of the Catalan bourgeoisie, in contrast to the stereotype of the “unproductive” capital of Madrid with its royal court and shallow culture of representation.

At first glance, this article appears to be just another instance in the construction of the mediatic figure of Avi. Yet the unsigned article did much more than simply regurgitate the stories that circulated in other newspapers. The journalist from Madrid talked at length with the director Darder and possibly with the keepers, gathering information on Avi’s life and his day-to-day experiences at the zoo. The article contains several anecdotes that portrayed Avi as an active animal, signalling what he liked and, in particular, what he disliked.

The first anecdote was related to a parade with exotic animals at the Granja Vella on Sunday, September 9, 1883, in which Avi participated. The occasion was the silver wedding celebration of the Catalan entrepreneur Camilo Fabra (1833-1902) hosted by Lluís Martí-Codolar. There were two accounts of the festivities, a contemporary one from 1883 and the one from Alrededor del Mundo, 16 years later. The report of 1883 only mentions “two camels, an elephant, a giraffe, and two golden and silver donkeys” participating.42 Avi had no name yet. In the article from 1899, the parade is described in a much more dramatic way. The animals “disguised” themselves and wore the skins of tigers and panthers. Avi immediately sensed the “fraud” and was deeply ashamed to have taken part in such an unworthy farce. He played along, “but since that day there has been no human means of making him work, not for anything, not for anyone. He adopted the form of protest that was most comfortable for him”.43

In 1883, the elephant had only been part of Martí-Codolar’s private zoo for at most two years and was still a blank slate in the eyes of the public. The enormous popularity of the elephant allowed the journalist from Alrededor del Mundo to re-imagine the animal parade. In retrospect, he ascribed Avi the leading role in an “Indian caravan”. The journalist interpreted the animal pageant of 1883 through the lens of 1899, that is to say, with the now-famous Avi in mind, projecting his personality back. Sharp intellect and irreverence were part of his character as well as his “refusal to work”.

Another anecdote featured Josep Collaso (1857–1926), several times mayor of Barcelona. During a visit to the zoo accompanied by Darder, Collaso twice tried to slip Avi an empty candy wrapper while both men laughed at the animal. While the elephant was forbearing the first time, the second time he knocked the mayor down with his trunk. Did the journalist embellish the story for dramatic effect? Possibly yes, but seen through the eyes of today’s ethology, Avi’s reaction seems plausible. Elephants do not take it lightly if they are deceived and might react violently. In any case, the message about Avi’s character, patient only to a point, was clear.

In yet another anecdote from the article in Alrededor del Mundo, illustrated by one of the drawings, Avi grasped one of the keepers with his trunk and deposited him on the roof of the elephant house (fig. 5). While this story defies credibility, there was a realistic backdrop. The keeper was new, and there is evidence from other sources that Avi reacted violently to this “intruder”. A newspaper article from 1897 (which may be the basis for this anecdote) reported that Avi was assigned a new keeper whom he struck down. The journalist suspected that the elephant was still very much attached to his old keeper.44 An article from 1914 told a similar story from Avi’s time at the Granja Vella. Once more, he had been assigned a new keeper, not the one he had gotten on so well with. Displeased with this situation, Avi went on a “hunger strike” until Darder understood what the problem was and reinstalled the old keeper.45 Avi seemed to have preferred keepers he knew to new ones — exactly what one would expect from a current perspective. Elephants build personal relationships with keepers and clearly show their preferences. Avi knew whom he trusted and was able to signal through his behaviour that he wanted the keeper he had been used to back. We might interpret this as resisting in the sense described by Nance, which is not with a capital R but a lowercase one.46

Fig. 5 Unhappy with the new keeper, Avi grabs him.

Alrededor del Mundo, 9 June 1899, 5; Biblioteca Nacional de España.

The close reading of the article in Alrededor del Mundo and other sources brings several instances of resistance or outright violence on Avi’s part to the fore. As regards the level of aggression, these episodes were mostly couched in harmless anecdotes that serve a double purpose. They are meant to entertain the readers, but also to “save” the creature’s benign character. The mediatic figure Avi could by no means be a rogue elephant. Journalists tended to attribute the elephant’s violent conduct to his sense of justice rather than animal resistance, or, as the Alrededor del Mundo article put it, his sense of “independence”.

In the same way that Avi’s occasional outburst or “obstructive behaviour” was glossed over or diluted with humour, the structural violence against him, both institutional (captivity, inadequate conditions and isolation) and public (mistreatment by visitors), was ignored, downplayed, or faded out. Yet again, a close reading of newspaper reports reveals several incidents in which Avi must have suffered. Contrary to the well-crafted narrative that the “perceptive” Avi always detected the dangerous objects passed to him as food, in all likelihood, he ingested cigarettes, needles, matches, or even some form of poison on numerous occasions.47 Once, the zoo personnel stopped Avi from swallowing a lockpick that might have killed him.48

On another occasion, the elephant had stuck his trunk over the outside wall of the zoo and a worker passing by had hurt him with an iron rod.49 Over the years, there were several reports of indigestion or, more generally, of the elephant being sick.50 In contrast to the direct agressions just mentioned, we might consider these features as forms of indirect violence.

In two articles of L’Esquella de la Torratxa, Avi’s seemingly uncontrolled consumption of buns and baguettes provided the occasion for social criticism. When the elephant seemed ill, Darder and the City Hall were alarmed, only to realize that it was merely indigestion, while so many people in Barcelona had not enough to eat.51 Contrasting supposedly well-fed zoo animals with the starving population of the urban lower classes was a widespread trope in newspaper articles on zoos, often more of a staple joke than serious criticism.52 Once more, a real problem of Avi’s everyday life was transformed into something else, namely entertainment, that had nothing to do with the underlying facts (as we know today): inadequate food.

According to these articles, Darder was able to help Avi when he was sick or injured. The zoo director, whom Avi had known since he picked him up in Genova, was portrayed as his continuous carer yet no specifics regarding the treatment were divulged.

Around 1900, the institution of the zoo was occasionally denounced as an “animal prison”.53 Criticism was launched at the miserable state in which the animals of the Barcelona Zoo, including the elephant, had to live out their existence.54 Avi’s condition as a captive was pointed out, using the word “slavery”.55 Yet this critical comment was reined in and placated immediately. “Comfortably settled, lacking nothing to make him happy — if one dispenses with the slavery in which he finds himself — with an enclosure in which to spread himself out”.56 The day after his death, one newspaper article summed up all the gossip around why Avi was in such a terrible state. According to one rumour, “he wanted to escape and broke a leg falling”.57 On this occasion, Darder could do nothing to save the star of his zoo. We may assume that many Barcelonese felt deeply saddened hearing about the loss of the animal they had visited, cheered, fed and touched so many times over the years. Yet as we saw at the start of the article, the media machinery, in particular the caricatures, was primed to draw entertainment even from Avi’s death.58

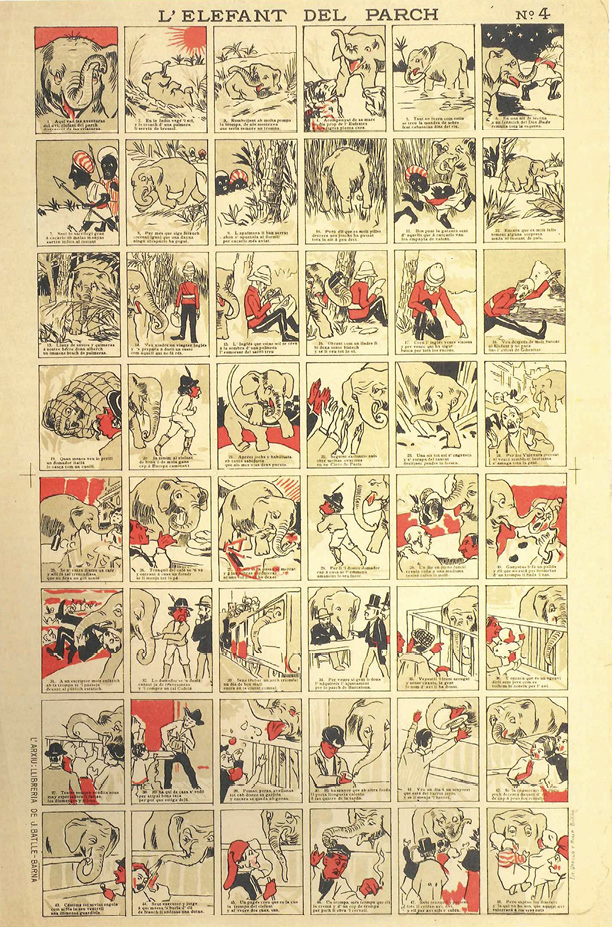

Avi’s Auca — the Life of an Elephant as a Comic

We shall now turn to the auca “L’elefant del Parch” from 1895, a visual biography of Avi telling his journey from the “Indian jungle” to the European metropolis (fig. 6). An auca is a large illustrated broadsheet print (in this case 55 × 35.5 cm) that contains forty-eight images, each explained by a short caption — a comic of sorts.59 These prints were sold at news-stands and bookstores, either loose or enclosed within a magazine. Their thematic spectrum was broad: everyday life, history, politics, even religion. There is no other auca dedicated exclusively to one individual animal, which underscores Avi’s high level of recognition among the Catalan public.

In the following, we shall first summarize the content of the auca and then discuss what clues we might glean from this visual source in order to reconstruct Avi’s biography. The first eighteen images narrate his life in India. In a sequence of six images, dark-coloured people (“Indians”) fail to capture Avi despite the use of various tricks. The clever elephant knows how to hide and chases his hunters (called “fanatics of the god Buddha”) away. Next, the artist’s imagination summons a British colonialist. The “English traveller” wears a pith helmet and eats a “bisteck” (beefsteak). Avi secretly steals a bottle of wine from him and uncorks it. The elephant is eventually captured by an “Italian tamer” who brings him to Europe, where he runs a circus. In the “Circus of Paris,” Avi quickly learns how to delight the audience with his tricks. But one night, he escapes and causes chaos and destruction on the “boulevard”. After having had coffee, he calms down and eats all the bread he can find in a bakery. Eventually, Avi is captured and reappears in the circus, yet he becomes uncontrollable, assaulting spectators during the performance.

Fig. 6 A biography in comic form: “L’elefant del Parch”.

Àmbit de Gràfics, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona, AHCB, Auc-74.

“Tired of his mischiefs,” the Italian circus director sells Avi to Martí-Codolar, and the elephant arrives in Barcelona by train. In the last fourteen images, his interaction with visitors is illustrated in a variety of ways: his insatiable hunger for rolls and fruit, the punishment of ill-intentioned men who try to slip him a lit cigarette qua splashing water, his love for children, and his characterization as “wise, calm, and patient”. This last part of the auca condensed the numerous press articles that described Avi’s behaviour, which we have looked at in the previous section.

The part dealing with the period before Avi arrived in Barcelona, i.e., his youth in India (replete with racist stereotypes and colonial imaginaries) and his time in a French circus, is a complete fabrication. We shall now tease out the implicit and explicit references of the auca to the circus. Uncorking a wine bottle, for example, was a typical trick that elephants performed in circuses at that time.60 The “Italian tamer” who brings Avi to Europe might have referred to the Italian animal trader and circus impresario Luis Cabañas/Luigi Cavanna (d. 1916), who had settled in Madrid. In 1883/84, Cavanna took charge of the “Casa de Fieras” (House of Beasts), a menagerie located in the Parque del Buen Retiro. He staged his animal show several times in Barcelona in the 1870s and 1880s.61 In other words, in 1895, the year of the auca’s creation, he would have been known well enough in Barcelona to figure as the “Italian tamer”.

The boundary between the circus and the zoo was permeable, especially with regard to show animals such as elephants.62 Often, zoo elephants had previously worked in the circus ring — or they even changed by season, i.e., they spent the winter in the zoo and the summer in the circus. Well documented is the case of the elephant Fritz, born in 1870 and nearly the same age as Avi. Fritz was part of the elephant group in the circus Barnum & Bailey, touring France in 1902. By then, Fritz was already considered relatively old (i.e., losing value) and “difficult” to handle. On a public parade through the city of Tours on June 11, 1902, the keepers temporarily lost control of the elephant. The senior manager of the circus, Joseph McCaddon, decided to put him down. Fritz was strangled in public.63 Similarly, in 1913, the German circus Sarrasani gave the elephant called Little Cohn to the Posen Zoo (today Poznań) because he could hardly be held in check anymore. He even escaped once, causing the circus director to wound the elephant with his revolver.64

Escapes of “wild” animals from zoos and circuses made international headlines at the time (as they still do today). These two episodes featuring Fritz and Little Cohn may be read as “counter-stories,” reflecting the violence circus elephants were subjected to in case of “deviant behaviour”. The artist of the auca could not have known about these posterior incidents. Yet he must have heard about the breakout of the elephant Pizarro in Madrid in April 1865, which eventually morphed into an oft repeated anecdote as he reimagined this part of the story with Avi on the boulevards of Paris. After leaving a trail of destruction in the city, Pizarro stopped at a bakery in the central Calle de Alcalá, stuffed himself with pastries and could hence be captured without difficulty.65

The readers of Spanish newspapers would regularly come across stories of circus elephants injuring or even killing people.66 Entertaining tales such as Pizarro in the Madrilenian bakery or the escape of Avi onto the boulevard in Paris were concocted for public consumption, glossing over the violence involved. Nevertheless, the circus section of the auca reflects at least some degree of reality of the life of elephants in Europe around 1900, moving in revolving doors between the circus and the zoo.

The auca can be understood as the artistic condensation of the presence of elephants in the Spanish public sphere at the end of the nineteenth century. We find a mixture of stereotypes as well as reality fragments concerning circus elephants. The auca includes the “mischiefs” perpetrated by Avi in the circus but transforms his “deviance” into visual entertainment.

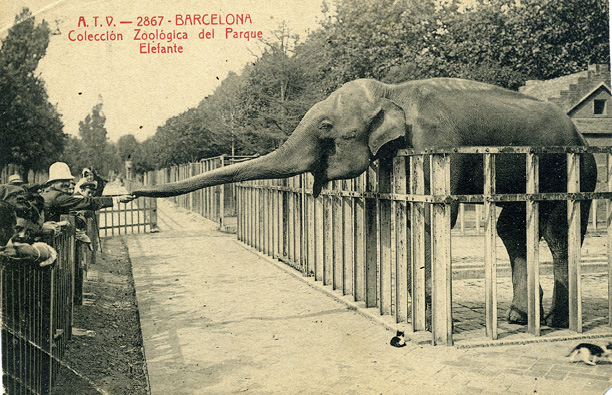

Avi in Action — Postcards as a Window to Animal Experiences

Avi entered the public stage in 1892 and rose to local and even national fame in the following years — “just in time” for the eruption of the postcard as a mass medium in Spain around 1900.67 The first postcard featuring Avi was likely published in 1902. By 1914, the year of his death, roughly seventy different postcards of the captive elephant had been issued.68 This enormous quantity and variety of these postcards provide the source corpus of this section. On one hand, it shows the carefully constructed image of Avi as a “happy” inhabitant of the Barcelona Zoo. On the other hand, from the perspective of current-day ethology (as consulted with Franziska Hörner), these postcards contain intriguing pointers to the real-life experiences of the Barcelona elephant.

Zoo postcards were commercial products and featured images that would appeal to customers, portraying the zoo as an amenable space where visitors would enjoy the exhibition of “exotic” animals. The enormous popularity of the elephant was of concrete commercial value in what has been labelled the “consumption of the exotic”.69 The postcards featuring Avi were produced and sold by private companies. Generally, these postcards formed part of a series, for example, showing the highlights of Barcelona. In other words, Avi featured alongside the cathedral or the Sagrada Familia as one of the major sites of the city. The fact that between 1902 and 1914 over seventy different motifs were printed, indicates that Avi-postcards were enduring bestsellers. Exact figures are difficult to come by, but the print run of a single postcard was in the thousands. It was not until 1909/10 that the Junta, the board overseeing the zoo, reacted and issued their own series of zoo postcards.70 The series included ten different animals including Avi, with a total print run of over thirty thousand. In an attempt to distance themselves from the more “sensationalist” postcards, the Junta deliberately opted for black-and-white postcards without the zoo background (in particular, without the visitors) and presenting the depicted animals not in motion, but still, as objects of zoology and hence, as a medium of instruction.

The private companies operated very differently in their image selection. Photos for Avi postcards were selected for their visual impact. The spatial context of the zoo (the elephant paddock, the visitors, the long row of enclosures) was more prominent in the Avi postcards than in most photos we know (which tend to focus more on the elephant alone). As much as possible, zoo postcards tried to avoid displaying the bars of enclosures to deter any notion of an imprisoned or even suffering animal. Many of these images created an idyllic or lively scene with the pachyderm as a central actor and the visitors as “extras,” sometimes as a smaller group of people, sometimes as a large crowd. The photos were often shot from the side with Avi to the right and the public to the left to capture their interaction. The postcards show the elephant raising his trunk in the air or reaching out over the fence, sometimes making direct contact with the public. Avi constantly begged for food from the visitors, opening his mouth so the onlookers could aim at it with the buns they had brought. Elephants need such large quantities of food that they basically never stop asking for it in a captive situation. The begging behaviour was not conditioned by the visitors; at most, it was enhanced. Ingesting so much bread, a poor diet (too much sugar and few nutrients), is detrimental to elephant teeth which wear out faster. At least one postcard shows the bad state of his dentition. Another feature that many of the postcards reveal, is the discolouration of his skin. There was a large white stain on the top of his head and a white line all along his spine. The lack of micro- and macronutrients in Avi’s diet might have been the cause of this dermatosis.

Avi lived in social isolation, without seeing another elephant for over thirty years. Smaller zoos never had more than one elephant at the time. Yet elephants are highly social animals. With today’s knowledge about the physiological and social needs of elephants, we understand the traumatic experiences that zoo elephants suffered around 1900.71

Completely isolated elephants have a short life expectancy. It seems reasonable that the visitors of the Barcelona Zoo provided Avi at least some form of social contact which helped him to carry on. In the vast majority of the postcards, the elephant was always positioned at the fence, his trunk directed at the visitors. Avi often stretched his trunk out over the barriers while people tried to touch it, as dozens of postcards show (fig. 7). For the zoo visitors, this was part of the ritual of visiting the elephant paddock, which Avi seems to have “enjoyed” too. There are numerous images of other zoo elephants from the same period, and the dramaturgy is the same. As Rothfels put it: “photographs of hands outstretched to trunks reside in the archives of every Western zoo”.72 Apart from a few minor incidents mentioned above, Avi seems to not have hurt anybody in twenty-two years despite it being a frequent occurrence for other zoo elephants at the time. This is even more remarkable given the daily close contact between the elephant and visitors. One postcard shows a boy sitting on the fence with his back to Avi, and easily within stroke distance of his powerful trunk — a very “risky” exposure. This suggests that Avi “behaved well” in the eyes of his human contemporaries. Conversely, judging by the visual evidence of the postcards, Avi showed no signs of mistreatment (wounds, scars, neglect). That might explain why, despite adverse conditions, he reached the high (for a zoo elephant at the time) age of over forty years. Darder and his keepers must have been capable of providing some basic care for Avi to grow that old, however inadequate it might be from a modern perspective.

Fig. 7 Touching Avi — the zoo visitor’s favoured pastime.

Postcard collection Assumpta Rafel, Barcelona.

The sources provide, at most, some indirect clues about what this care consisted of. A critical issue with captive elephants is the growth of their toenails due to the reduced wear, as they walk far less than in the wild. The photo of the dead Avi (see fig. 2) shows that the toenails of the front legs had been trimmed while the ones of the hind legs were overgrown. The postcards on which the toenails are visible show no overgrowth. This indicates that the Barcelona Zoo was aware of the need to cut them.

Many of the postcards show evidence of the activity of Avi’s temporal glands. These glands, situated halfway between the eyes and ears, produce a secretion related to emotions. The secretion exudes a strong smell and is a means of attracting attention. One postcard shows a dark ring around the temporal glands indicating a very recent secretion. Some postcards show a white scabby crust (generally rare), indicating that the secretion has hardened and that the temporal glands were very active. The secretions could be related to stress and negative sensations but also (less frequently) to joyful experiences.

The interpretation of the seventy Avi postcards is a very good example how pictorial sources may be read against their original intentions (to entertain their buyers by suggesting that Avi led a happy life in the Barcelona Zoo) in order to reconstruct, at least to some degree, his real-life experiences.

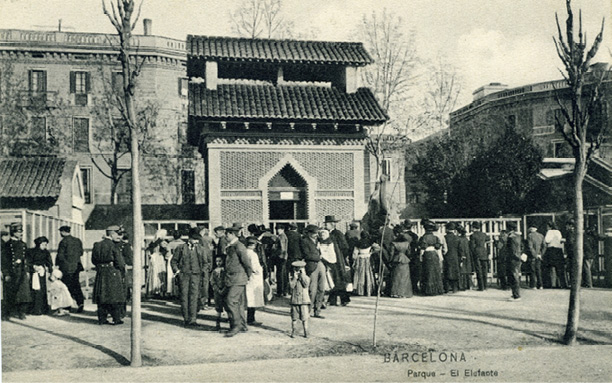

Avi’s Architecture — Living in Restricted Quarters

This section deals with the enclosures that were designed for Avi to stage him as an “exotic” creature. At the same time, it tries to reconstruct what this orientalist architecture meant for the everyday life of the elephant. Already during his time at the Granja Vella, Avi was housed in a paddock with a peculiar outlook. The roof consisted of a semicircle with an ornament at the top (see fig. 3). In the zoo there was an “elephant tower” (our term) at the back of Avi’s paddock, a tall but not very wide building including a merely ornamental roof (see fig. 8). Its architectural style may be considered to be neomudéjar, characterized by uncovered brick and orientalizing elements such as the pointed entrance. It was built by municipal architect Pere Falqués, known for his peculiar style, who oversaw the construction of the buildings in the Parc de la Ciutadella.73 Falqués built several markets in Barcelona with high roofs. These were supposed to provide sufficient ventilation, and it seems that the construction of the “elephant tower” followed the same rationale.74

If we contextualize Avi’s enclosure within zoo architecture of the late nineteenth century, both parallels and differences, owed to the local context, emerge. To present animals from other continents as “exotic,” animal houses were built while taking part in the cultural appropriation of non-European fauna. The temples, palaces and pagodas in Western zoos were meant to evoke the animals’ countries of origin.75 As Dorothee Brantz put it: “This conflation of animal displays and cultural signification underscored how zoos functioned to cultivate nature and simultaneously naturalize culture.”76 The most emblematic example of this “zoo orientalism” was the monumental elephant pagoda built in 1873 in the Zoologische Garten of Berlin. “Peripheral” zoos attempted similar feats on a smaller scale.77

Avi’s tower may hardly be described as an Indian temple, unlike, for example, structures in other “peripheral” zoos. In Adelaide, Basel, and Buenos Aires, the elephant was housed in a temple-like structure that was supposed to evoke “India” in the eyes of the visitors.78 The eclectic style of the Barcelona elephant tower refers in a more idiosyncratic way to the “Orient” rather than specifically to India. This would support the argument that the imaginaries created around Avi lacked an explicit colonial dimension. Rather, the elephant tower needs to be understood in the framework of Falqués’s municipal architecture.

Fig. 8 Avi’s “elephant tower”.

Postcard collection Assumpta Rafel, Barcelona.

Now, let us ask how far the enclosure corresponded to the needs of an elephant. The paddock contained a small square water-filled pond for Avi to drink from and to spray the visitors on occasion. The pond was very shallow, more like a waterhole. In 1893, Darder claimed that the elephant “has a bath sufficiently large for the space allowed by the facility in which he is being held, for solace during the hot season,” but it seems like that was a massive exaggeration.79

From a modern perspective, the cramped housing of Avi’s enclosure was entirely inadequate. His rectangular paddock might have at most measured eight metres (breadth) by around ten metres (depth); so roughly eighty square metres including the surface of the building. The ground was covered with cobblestones. The enclosure was bounded by a metal fence of around two metres in height. It allowed Avi to nudge his head over the fence and direct his trunk to the visitors. As was the custom in many zoos at the time, the visitors had to stay behind a (smaller) fence, leaving a space of around two and a half metres between the two fences. In the enclosures next to the elephant paddock, the distance between the two fences was only about half as much. Yet this range still allowed for physical contact between the end of the outstretched trunk of the elephant and the extended arm of the visitor (see fig. 7). This proximity enabled several ways of interacting, such as touching the tip of the trunk or handing the elephant food.

Being the major attraction of the zoo, his enclosure was constantly beleaguered with onlookers expecting him to react to their cheering. This must have meant a high level of stress for Avi. Yet as Darder observed early on, when Avi had eaten enough buns, he withdrew “from public view, taking refuge in the chalet that serves as his bedroom and closing the door himself”.80 So it seems as if the construction of his lodgings, in particular the door of the tower, allowed for some autonomy that Avi made good use of. The elephant went inside “so nobody would disturb him,” a magazine article claimed. If they called on him, he would open the door to see what they wanted. “What he does not allow is the door being closed from outside. He gets furious and destroys everything when he feels like a prisoner and breaks down the door.”81 (It was this iron door where he hurt himself fatally in 1914.)

Although it was never mentioned in the sources, Avi was likely chained during the nighttime, as was common practice in the zoos at the time (and is still practised today in some zoos). Only the photo (see fig. 2) of the dead Avi (and there are well over a hundred photos of the living Avi) shows a rope tied to his back right foot. This photo also provides the best evidence of the surface of the paddock — it was covered with cobblestones. Part of the ground had been ripped up, perhaps in an effort to make it softer during his last agonizing days, as a pile of cobblestones is visible just outside the fence, and the dead Avi lay on the bare soil. From today’s perspective, a hard surface (stones or concrete) is detrimental to the health of the feet of elephants; sand is much better. In none of the photos are the soles of Avi’s feet visible, but they might not have been in a good state, given the constant exposure to the hard surface.

So far, no sources on the planning of the elephant enclosure could be found. The elephant tower was probably occupied by Avi’s successors until the early 1960s, when the Barcelona Zoo underwent major reconstructions and expansion.82 It was then torn down to be replaced by a different kind of enclosure for smaller animals. The lower part of the former “elephant tower” is still physically there. As of 2025, it is at the back of an empty enclosure, covered and not recognizable from the outside. These small rooms serve as a storage space “behind the scenes” of the zoo and are only accessible to zoo personnel. The open red bricks where Avi rested at night are still visible.83

Avi’s Afterlife — a Skeleton Full of Clues

This section contrasts the popular narratives about the “famous elephant” that have been spun since Avi’s death with clues that this mortal remains, his skeleton, may hold. Even though in May 1915 an elephant named Júlia replaced Avi, and the Barcelona Zoo has had at least one elephant ever since, he remains by far its best-known elephant.84 Both the Barcelona Zoo and the Natural History Museum fully appropriated Avi beyond his death.85 The elephant is still very present in the way the zoo commemorates its history.86 Avi also prominently figures in the “history section” of the zoo’s website.87 In popular accounts and in newspaper articles addressing the history of the zoo, Avi is often mentioned.88

His story rewrites itself over and over again using a more or less fixed set of elements. The main ingredients are his provenance from the collection of Martí-Codolar, that the Catalans called him Avi because they could not pronounce “Baby,” that he was very popular, and that he became the first “animal star” of the Barcelona Zoo, long before the famous albino gorilla Floquet de Neu (ca. 1965–2003).

Avi’s lasting fame is also due to his continued physical presence as a museum object. As the dead Avi “predicted” in the caricature, he was indeed stuffed and also mounted as a skeleton. His mortal remains were transformed by Lluís Soler i Pujol, the taxidermist of the museum and a disciple of Darder.89 Already in late January 1915, both Avi’s skeleton and his taxidermically prepared hide were exhibited side by side first in the Museu Martorell and then, since 1917, in the nearby Castell de Tres Dragons, which was the main building of the Natural History Museum until 2010 when that site was closed to the public.90 While the hide had to be discarded in the 1980s due to degradation, the skeleton was restored in 2008. In an exhibition on the history of natural history museums entitled “Nature or Culture”, which ran from December 2023 to July 2025, Avi’s skeleton was the first object to greet the visitor entering the site (see fig. 9).91 Both buildings, the Museu Martorell and the Castell de Tres Dragons, are located on the other side of the Parc de la Ciutadella, just a few hundred meters away from where Avi’s elephant tower stood. In other words, with short interruptions, his skeleton has been on display for over a century, and several generations of visitors, including numerous school classes, were told the story of Avi.

The afterlife of famous animals as museum exhibits has already caught the attention of historians.92 Sam Alberti argues that the transition from the zoo to the museum is not a matter of “a simple passage from nature to culture […] Zoo elephants […] are a blend of cultural and natural”.93 There are numerous examples of zoo or circus elephants who have been exhibited for well over a century, such as Maharajah (taxidermy in two museums in Manchester), Jumbo (skeleton in the American Museum of Natural History, New York), or Fritz (taxidermy in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Tours). The skeleton of Little Cohn was exhibited between 1929 and 1944 in Poznań’s Collegium Anatomicum, when it was destroyed by an air raid.94 These museum mounts serve as crystallization points to tell and retell the life story of the elephants.

Yet Avi’s skeleton might also hold information with respect to the corporeal elephant. His remains reveal that he did not suffer from arthrosis. The bones of the extremities appear to be in good condition and were not worn down. The lesion of the front left leg is visible insofar as a small part of the bone is missing. It had been patched over with a white mass, probably already by Soler i Pujol. With one leg injured, Avi would not have ventured to lie down for fear of not getting up again. A possible scenario is that the wound led to an infection that eventually caused a fatal sepsis. This would explain Avi’s sudden collapse on 1 May 1914.

Fig. 9 The skeleton of Avi, greeting the visitors to an exhibition in the Museu Martorell.

Museu de Ciències Naturals de Barcelona.

For some time, zoologists had suspected that Avi was, in fact, a female. Male elephants periodically enter a state called musth, “which usually produces erratic and aggressive behavior”.95 There are no reports that Avi turned exceedingly difficult at any stage and as mentioned before, there were hardly any incidents where people got hurt. Avi initially had no tusks and only grew some short ones, called tushes, later on, as is the case with roughly fifty percent of female Asian elephants; the other half not growing any at all. The upper part of the skull of a male is domed and has two cusps, while the skull of females is rather flat. The shape of Avi’s skull is ambiguous and does not provide clear evidence.

The skeleton also offers a pathway to Avi’s genetic code. In 2023, a DNA sample was extracted from an upper-thigh bone, but the quality of the material proved insufficient to determine Avi’s sex. A second attempt in November 2025 was more successful: according to the DNA sequenced Avi was indeed a female. Further DNA analysis could even provide clues about Avi’s geographic origin, i.e., where exactly in Southeast Asia the elephant was born.96 Writing his, or rather, her biography is an ongoing process.

Alternative Avis — an Ongoing Biography

This article started by contrasting two visualisations of the dead Avi: a caricature meant to entertain and a shocking photo of the lifeless body. In the course of this article, we surveyed a large number of sources, textual, visual, and material: newspaper and magazine articles, the auca, postcards, the elephant enclosure, and Avi’s skeleton.

The media coverage, enhanced by visual media such as caricatures, created the public persona of Avi in collaboration with the zoo-going Barcelonese. Although this persona was made up of a diverse assembly of tropes and imaginaries, some stable features emerged. Avi was constructed as a respected “citizen” of Barcelona, a friend of children, as wise and justice-loving. He was patient and forgiving to a point, but would castigate evildoers. This character, along with his name recognition in the public sphere, even turned him into a reference point for Catalan politics.

Throughout the article, we have tried to draw parallels with other zoo or circus elephants, and there are indeed many. This comparison showed that each local context conditioned their appropriation. The specific historical constellation of fin-de-siècle Barcelona distinguished the case of Avi from the nationalist or imperialist appropriations of other celebrity elephants of the time, such as Jumbo. He was neither framed as a colonial trophy, nor did he epitomise the (declining) colonial power of Spain (as was the case with other European colonial powers). Rather, the elephant became a prism for the enormous social tensions of the time.

Depending on the medium, Avi’s characterisation oscillated between different political factions: the increasingly nationalist Catalan bourgeoisie, the republican, and left-leaning voices, all using the elephant to espouse their social critique. Publications such as El Diluvio and L’Esquella de la Torratxa fashioned Avi as a watchdog of the ruling elites. These overlapping images resulted in anything but a monolithic persona. The mediatic figure Avi thus also reflected different attempts of appropriation. Thus the tensions of Barcelona and Catalan culture around 1900 along the two fault-lines we named: national identity and social class.

This article set out to recover the “real” Avi, i.e., to reconstruct the experiences of Barcelona’s first zoo elephant. To disentangle the corporeal Avi from mere cultural representations of the animal turned out to be a historiographical challenge, as the former can be reconstructed to a large degree only by using the latter. The entertaining piece in Alrededor del Mundo is also the source that provides the most clues for reconstructing Avi’s agency. Even in a medium as fully geared toward public consumption and entertainment as the auca, we could discern some reality fragments about elephants in circuses. To insist on a fundamental distinction between the two, the material and the mediatic, does not seem feasible, as they are so closely interwoven.

Screening the newspaper articles for evidence of Avi resisting, or at least reacting in specific ways, to the situation he was subjected to proved fruitful. It seems that he was able to maintain a certain degree of autonomy: retaining the keeper he was used to and interacting with the zoo crowd for as long as he felt like it before withdrawing into his tower which he arguably considered his refuge, closing the door after himself. Although the idea of “elephantine justice,” which El Diluvio used as a title for one of their articles, is a human trope, this is not to say that Avi did not react in a very specific way to visitors who intended to annoy or even hurt him, a behaviour that we humans might call retributive.

Avi’s “deviant” or even violent behaviour towards some visitors and new keepers was routinely glossed over by the journalists reporting on the star of the zoo. The image the Catalan media had created of Avi would not allow for negative character traits. This would have only changed, as happened to other zoo or circus elephants at the time, if Avi had committed a “true” misdeed such as killing a keeper (as Fritz had done) or becoming entirely uncontrollable (as Gunda allegedly had).97

This Barcelona case study suggests that we need to understand zoo animals as historical, i.e., individual actors. Searching for the corporeal Avi, or however the elephant in question might be called, might yield different elephantine personalities, and in the long run, with more case studies of captive elephants, a broader and nuanced picture of how they adapted and reacted to life in a zoo or circus might emerge. The richness of this case from the early Barcelona Zoo highlights the need to overcome the narrow focus on the anglophone world. In this way the alleged periphery could become epistemologically productive.

As the case of Avi also has shown, zoos and museums tend to maintain the well-trodden narratives of their celebrated elephants. These stories provide entertainment even today, featuring “colourful personalities” such as Avi, and are often not questioned on their veracity. It is probably no coincidence that many of the cases mentioned in this article are from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, long enough ago not to turn into a PR problem, as modern zoos have long abandoned the entirely inadequate animal keeping of those “horrible times”.

Still, this article would like to raise the question of how a zoo or a natural history museum should commemorate a celebrity animal that is still present, physically as a skeleton or taxidermy, and discursively in the numerous accounts of his life that are being regurgitated and retold over and over again. Who should write Avi’s biography? In particular, zoos might be hesitant to tell alternative stories of elephants that had been in their care over a century ago. The Barcelona Zoo is regularly in the line of fire of animal rights activists, and the keeping of the elephants currently displayed there has been severely criticized in the last years as inadequate. Like any other zoo, the Barcelona Zoo tries to avoid bad press. Still, this does not mean that less sanitized and more realistic narratives about historic zoo animals are not possible (see fig. 10).

Acknowledgements

As stressed throughout this article, this research crucially depended on animal experts of all sorts. For their help with the sources and all the conversations, comments and criticisms I would like to thank Vanessa Almagro, Wessel Broekhuis, Santos Casado, Mavi Corell Doménech, Damià Gibernet, Franziska Hörner, Nicolás Kwiatkowski, Leoncio López-Ocón, Joan Molet Petit, Pilar Padilla, José Pardo-Tomás, Javier Quesada, Martín Rodrigo y Alharilla, José María Santamaría, Angela Stöger, Laura Valls Plana and Rosa Vives Piqué. The two anonymous reviewers provided essential feedback. My greatest debt is to the two editors of this dossier who always believed in me and Avi. This article is part of the project I+D+i PID2020-112514GB-C21, financed by AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Fig. 10 Imagining a different Avi.

Altered postcard by Spanish artist Rosa Vives Piqué, 2024.

Notes

AH-MCNB-id1970, 1–2; El Diluvio, 3 May 1914, Ed. Mañana, 19.

La Vanguardia, 3 May 1914, 3; La Veu de Catalunya, 4 May 1914, Ed. Matí, 2; Papitu, 6 May 1914, 282; ¡Cu-Cut!, 7 May 1914, 308–10; L’Esquella de la Torratxa, 8 May 1914, 305, 310–11.

¡Cu-Cut!, 14 May 1914, 323.

L’Esquella de la Torratxa, 8 May 1914, 305. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are my own.

A common practice in the Barcelona Zoo during the summer, La Publicidad, 20 August 1893, 2.

Simons, Obaysch, xiii, makes a similar case for Obaysch.

Simons, Obaysch, 83; Nance, Entertaining Elephants.

Baratay, Biographies animales; Roscher and Krebber, Animal Biographies; Pouillard, “Animal Biographies”.

Simons, Obaysch, 9; Rothfels, “The Elephant”.

Rothfels, “The Elephant”, 230.

Nance, Entertaining Elephants; Rothfels, “Elephants, Ethics, and History,” “Touching Animals,” Elephant Trails, “The Elephant”.

Szczygielska, “Elephant Empire” and “Animating Capture” on Eastern European elephants.

Loisel, Histoire des ménageries, 110.

See, for example, Hochadel and Nieto-Galan, “How to Write”.

Hochadel, “A Global Player”.

It might be too early to speak of a “field” of animal celebrity studies, as the literature is quite diverse or even disperse; Giles, “Animal Celebrities”; White, “Tony the Wonder Horse”; Avery et al., Miss Clara.

The literature on Jumbo is enormous. Particularly insightful are Nance, Animal Modernity; Sethna, “The Memory”; Yeandle, “Jumboism”.

Szczygielska, “Animating Capture,” 21.

Darder, “Parque zoológico,” 1.

On Darder, Hochadel and Valls, “De Barcelona a Banyoles”.

Alberdi and Casasnovas, Martí-Codolar, 181–85.

For the history of the Barcelona Zoo see: Pons, El parc zoològic; Carandell Baruzzi, De les gàbies; Carandell Baruzzi and Hochadel, “El Zoo de Barcelona”.

Darder, “Parque zoológico,” 1; Gili, “Excursió col·lectiva,” 45; El Diluvio, 3 May 1914, Ed. Mañana, 19.

Jonch, El Zoo de Barcelona, 49.

La Ilustración Musical, 15 September 1883, 4; Gili, “Excursió col·lectiva,” 45; El Fusilis, 7 May 1886, 4.

¡Cu-Cut!, 7 May 1914, 309.

Darder, “Parque zoológico,” 1; Alrededor del Mundo, 9 June 1899, 4.

First: “l’avi Boby,” La Esquella de la Torratxa, 6 September 1895, 570; “Avi” first used as only name in 1896: La Esquella de la Torratxa, 25 December 1896, 820.

Pons, El parc zoològic, 91.

El Diluvio, 29 September 1893, 1; El Diluvio, 23 October 1906, 2; visualized in the auca.

Diario de Barcelona, 29 September 1892, Ed. mañana, 11316; La Vanguardia, 4 October 1892, 2; El Diluvio, 23 July 1893, 5; La Esquella de la Torratxa, 6 September 1895, 570; La Esquella de la Torratxa, 3 January 1913, 14–15.

El Diluvio, 29 September 1892, 8221; for elephants in US zoos, in particular the Boston Zoo and the very similar media coverage of The Post: Hanson, Animal Attractions, 66-67.

Rothfels, Elephant Trails, 45.

Alberti, “Maharajah”.

Bender, The Animal Game; Rothfels, Elephant Trails, ch. 4.

Ealham, Anarchism.

La Esquella de la Torratxa, 1 October 1896, 631; La Esquella de la Torratxa, 25 December 1896, 820; La Campana de Gracia, 25 July 1908, 3; ¡Cu-Cut!, 7 May 1914, 308–10.

L’Avi. Setmanari satirich, no. 7/1906, 1–4.

El Diluvio, 29 November 1892, 10134; El Diluvio, 23 October 1906, 2; El Diluvio, 30 March 1909, 17.

Using a well-known elephant as a proxy in the public debate about class (and race) was particularly pronounced in the case of Jumbo (1860–1885) who figured as an “African” or as a slave; Sethna, “The Memory,” 35; Yeandle, “Jumboism,” 51.

On Jumbo: Nance, Animal Modernity; Sethna, “The Memory”; Yeandle, “Jumboism”; on elephants in German imperialism Breuer, “Der ‘erste deutsche Elefant’”; also see Hochadel, “Wild at Heart,” 175–79.

La Ilustración Musical, 15 September 1883, 4.

Alrededor del Mundo, 9 June 1899, 4.

L’Esquella de la Torratxa, 16 July 1897, 445–46.

L’Esquella de la Torratxa, 8 May 1914, 310–11.

Nance, Entertaining Elephants, 9-10. Also see Pearson, “Beyond ‘Resistance’”; Pouillard, “The Silence”.

El Diluvio, 26 November 1892, Ed. Mañana, 10066.

La Publicidad, 4 May 1899, 2.

La Dinastía, 9 May 1896, 2.

Darder, “Parque zoológico,” 1; La Vanguardia, 10 October 1896, 2.

L’Esquella de la Torratxa, 2 December 1892, 788; L’Esquella de la Torratxa, 4 June 1897, 342–43.

Hochadel, “Wild at Heart,” 75.

Rothfels, Elephant Trails, 87, on the “imprisonment” of the elephant Gunda in the New York Zoo around 1900.

For a particularly sharp criticism of Darder and the City Hall which accuses them of neglect, see El Diluvio, 30 March 1909, 17.

Alrededor del Mundo, 9 June 1899, 4.

Guibernau, Barcelona, s.p.

La Vanguardia, 2 May 1914, 8.

¡Cu-Cut! 13.27, 7 May 1914, 308; L’Esquella de la Torratxa, 8 May 1914, 305; L’Esquella de la Torratxa, 10 July 1914, 456–57.

Mestre, Diccionari d’Història, 75.

Rothfels, “Elephants, Ethics, and History,” 101.

December 1876 to March 1877, May/June 1887, and again between May and August 1888; March, Barcelona Freak Show, 125–27.

Bender, The Animal Game; Rothfels, Elephant Trails, 155.

Nance, Entertaining Elephants, 162–64; Ménager, La tragique histoire.

Szczygielska, “Elephant empire,” 799; Szczygielska, “Animating Capture,” 19.

La Discusión [Madrid], 6 April 1865, 3; La Ilustración Española y Americana, 8 July 1873, 419–20; Simón, El Retiro, 67–130.

Two examples from 1882: La Vanguardia, 21 August 1882, 5 (circus elephant escaping and injuring people in Troy, Michigan, US); La Vanguardia, 8 November 1882, 2 (elephant killing a woman in Rouen, France).

Teixidor Cadenas, La tarjeta postal.

Postcard collection of Assumpta Rafel, Barcelona.

Jones, “The Sight of Creatures”.

AH-MCNB, Id0605.

The detrimental effects of social isolation to the well-being of elephants in captivity have been amply documented, e.g., Kurt and Garai, “Stereotypies”. Also see Wemmer/Christen, Elephants and Ethics.

Rothfels, “Touching Animals,” 43.

Molet, Pere Falqués.

Information provided by Joan Molet.

Wessely, Künstliche Tiere, 99–102; also Rothfels, Savages and Beasts, 35.

Brantz, “Metropolitan Natural Histories,” 34.

Loisel, Rapport, 152.

Anderson, “Culture and Nature,” 282; Burkhardt, Der Zoologische Garten, 31; Coutaud, “Le Jardin Zoologique”.

Darder, “Parque zoológico,” 1.

Darder, “Parque zoológico,” 1. One may doubt though that the elephant withdrew voluntarily as long as there was a prospect of receiving more food (Franziska Hörner).

Alrededor del Mundo, 9 June 1899, 4–5.

Carandell, De les gàbies.

This discovery was made by the Barcelona Zoo keeper Damià Gibernet. I thank him for showing me around this “backstage area”.

Except for a few years around 1940, Jonch, El Zoo de Barcelona, 49–55.

See, e.g., Masriera, El Museu Martorell, 60.

Jonch, El Zoo de Barcelona, 49; Pons, El parc zoològic, 21, 44, 48, 51–53; Venteo, “La Ciutadella,” 45–46.

https://zoobarcelona.cat/es/conoce-el-zoo, last accessed 15 July 2025.

E.g., Catanzaro, “Animales ocultos”; Theros, “El primer zoològic”; March, Barcelona Freak Show, 108–110.

Viladevall and Carandell, El Taxidermista, 81–82.

El Diluvio, 27 January 1915, 1; La Vanguardia, 1 February 1915, 2; El Día gráfico, 8 February 1915, 6.

https://museuciencies.cat/en/exposicio_temporal/natura-o-cultura, last accessed 15 July 2025. The author of this paper collaborated in the design of the exhibition.

Alberti, The Afterlives.

Alberti, “Maharajah,” 52.

Szczygielska, “Animating Capture,” 38.

Irwin, Stoner and Cobaugh, Zookeeping, 299; on the issue of musth in Asian elephants see LaDue et al., “Social Behavior”.

Information provided by Javier Quesada.

Rothfels, Elephant Trails, ch. 4.

Works Cited

Alberdi, Ramón, and Rafael Casasnovas. Martí-Codolar, una obra social de la burguesía. Barcelona: Obra Salesiana Martí-Codolar, 2001.

Alberti, Samuel, ed. The Afterlives of Animals: A Museum Menagerie. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011.

Alberti, Samuel. “Maharajah the Elephant’s Journey: From Nature to Culture.” In Alberti, The Afterlives of Animals, 37–57.

Anderson, Kay. “Culture and Nature at the Adelaide Zoo: At the Frontiers of ‘Human’ Geography.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 20 (1995): 275–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/622652.

Avery, Charles, Helen Cowie, Samuel Shaw, and Robert Wenley, eds. Miss Clara and the Celebrity Beast in Art, 1500–1860. London: Paul Holberton, 2021.

“El ‘Avi’ de Barcelona. Un elefante original.” Alrededor del Mundo, 9 June 1899, 4–5.

Baratay, Éric. Biographies animales. Des vies retrouvées. Paris: Seuil, 2017.

Bender, Daniel E. The Animal Game. Searching for Wildness at the American Zoo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Brantz, Dorothee. “Metropolitan Natural Histories: Inventing Science, Building Cities, and Displaying the World.” In Science in the Metropolis. Spaces and Constellations of Scientific Knowledge 1848–1918, edited by Mitchell G. Ash, 25–42. London: Routledge, 2020.

Breuer, Lindiwe. “Der ‘erste deutsche Elefant’. Ein kamerunischer Elefant auf Bestellung.” In Atlas der Abwesenheit. Kameruns Kulturerbe in Deutschland, edited by Andrea Meyer and Bénédicte Savoy, 185–95. Berlin: Reimer, 2023.

Burkhardt, Louanne. Der Zoologische Garten Basel 1944–1966. Ein Selbstverständnis im Wandel. Basel: Schwabe, 2021.

Carandell Baruzzi, Miquel. De les gàbies als espais oberts. Història i futur del Zoo de Barcelona. Barcelona: Alpina, 2018.

Carandell Baruzzi, Miquel, and Oliver Hochadel, eds. “Dossier: El Zoo de Barcelona des d’una perspectiva global.” Actes d’Història de la Ciència i de la Tècnica n.s. 16 (2023): 41–146.

Catanzaro, Michele. “Animales ocultos.” El Periódico, 22 October 2007, 33–35.

Coutaud, Albert. “Le Jardin Zoologique de Buenos Aires, Argentine.” La Nature 40, no. 2039 (June 1912): 55–59.

Darder, Francesc. “Parque zoológico municipal de Barcelona. XI y último.” La Vanguardia, 9 February 1893, 1.

Ealham, Chris. Anarchism and the City: Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Barcelona, 1898–1937. Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2010.

Giles, David. “Animal Celebrities.” Celebrity Studies 4 (2013): 115–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2013.791040.

Gili, Raymond. “Excursió col·lectiva y visita oficial á la col·lecció zoológica de D. Lluís Martí y Gelabert, en lo terme d’Horta. Dia 6 de juliol de 1884.” Butlletí de la Associació d’Excursions Catalana 7 (1885): 43–48.

Guibernau, Juli Francesc. Barcelona á la vista. Album de fotografías de la capital y sus alrededores. Barcelona: Librería Española, [n.d.].

Hanson, Elizabeth. Animal Attractions: Nature on Display in American Zoos. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Hochadel, Oliver. “A Global Player from the South. The Jardín Zoológico de Buenos Aires and the Transnational Network of Zoos in the Early Twentieth Century.” História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos 29, no. 3 (2022): 789–812. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59702022000300012.

Hochadel, Oliver. “Wild at Heart: Zoological Gardens and the Urban Space.” In Urban Narratives about Nature. Socio-Ecological Imaginaries between Science and Entertainment, edited by Carlos Tabernero, 65–85. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2024.

Hochadel, Oliver, and Agustí Nieto-Galan. “How to Write an Urban History of STM on the ‘Periphery’.” Technology and Culture 56, no. 4 (2016): 978–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2016.0117.

Hochadel, Oliver, and Laura Valls. “De Barcelona a Banyoles. Francesc Darder, la història natural aplicada i la Festa del Peix.” In Dels museus de ciències del segle XIX al concepte museístic del segle XXI. Cent anys del Museu Darder de Banyoles, edited by Crisanto Gómez, Josep Maria Massip and Lluís Figueras, 23–41. Banyoles: Centre d’Estudis Comarcals Banyoles, 2017.

Irwin, Mark D., John B. Stoner, and Aaron M. Cobaugh, eds. Zookeeping: An Introduction to the Science and Technology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Jonch, Antoni. El Zoo de Barcelona. Educació i espai. Barcelona: Diàfora, 1982.

Jones, Robert W. “‘The Sight of Creatures Strange to Our Clime’: London Zoo and the Consumption of the Exotic.” Journal of Victorian Culture 2, no. 1 (1997): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13555509709505936.

Kurt, Fred, and Marion Garai. “Stereotypies in Captive Asian Elephants: A Symptom of Social Isolation.” A Research Update on Elephants and Rhinos. Proceedings of the International Elephant and Rhino Research, Vienna, June 7–11, 2001, 57–63. Münster: Schüling, 2002.

LaDue, Chase A., Rajnish P. G. Vandercone, Wendy K. Kiso, and Elizabeth W. Freeman. “Social Behavior and Group Formation in Male Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus): The Effects of Age and Musth in Wild and Zoo-Housed Animals.” Animals 12, no. 9 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12091215.

Loisel, Gustave. Histoire des ménageries de l’Antiquité à nos jours. Vol. 3: Époque contemporaine (XIXe et XXe siècles). Paris: Doin, 1912.

Loisel, Gustave. Rapport sur une Mission Scientifique dans les Jardins et Établissements Zoologiques Publics et Privés des États-Unis et du Canada, et conclusions générales sur les jardins zoologiques. Nouvelles Archives des Missions Scientifiques. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1908.

March, Enric H. Barcelona Freak Show. Història de les barraques de fira i espectacles ambulants del segle XVIII al 1939. Barcelona: Viena Edicions i l’Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2021.

Masriera, Alicia, ed. El Museu Martorell, 125 anys de Ciències Naturals (1878–2003). Barcelona: Institut de Cultura de Barcelona, 2006.

Ménager, Camille. La Tragique Histoire de Fritz l’éléphant. 52 min. France: ARTE, 2023.

Mestre i Campi, Jesús, ed. Diccionari d’Història de Catalunya. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1998.

Molet Petit, Joan. Pere Falqués, l’arquitecte municipal de la Barcelona modernista. Barcelona: Àmbit Serveis Editorials i Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2024.

Nance, Susan. Animal Modernity: Jumbo the Elephant and the Human Dilemma. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Nance, Susan. Entertaining Elephants. Animal Agency and the Business of the American Circus. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

Pearson, Chris. “Beyond ‘Resistance’: Rethinking Nonhuman Agency for a ‘More-than-Human’ World.” European Review of History 22, no. 5 (2015): 709–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13507486.2015.1070122.

Pons, Emili. El parc zoològic de Barcelona. Cent anys d’història. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1992.

Pouillard, Violette. “Animal Biographies: Beyond Archetypal Figures.” Journal of Animal Ethics 12, no. 2 (2022): 172–78. https://doi.org/10.5406/21601267.12.2.07.

Pouillard, Violette. “The Silence and the Fury. Addressing Animal Resistance and Agency through the History of Human-Animal Relationships.” In Animals Matter: Resistance and Transformation in Animal Commodification, edited by Julien Dugnoille and Elizabeth Vander Meer, 32–55. Leiden: Brill, 2022.