Becoming Pheasant

The Making, Unmaking, and Remaking of a Hunted Bird

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.19718

Keywords: conservation; stewardship; wildlife management; game animal; animal history; hunting; landscape

Eugenie van Heijgen is a lecturer at the Forest and Nature Conservation Policy group at Wageningen University, where she also earned her PhD in 2025 in the Cultural Geography group. This article is part of her doctoral research, in which she examines hunting landscapes in the Netherlands as co-shaped multi-species assemblages through time and space. In her work, she explores how hunting has historically shaped human–animal–landscape relations, as well as our understanding of species, the wild, and conservation itself.

Email: eugenie.vanheijgen@wur.nl

Humanimalia 15.2 (Summer 2025)

Abstract

Pheasants have long been considered the most hunted bird species in the world. No other “hunting animal” has been bred, released, and shot for as long and as intensively as the pheasant. In the Netherlands, after centuries of actively shaping these birds and the landscapes in which they were hunted, the rearing and release of pheasants is now prohibited. Yet this hunting legacy still shapes how pheasants are regarded — or disregarded — in contemporary nature conservation and management. By analysing historical hunting documents, interviews, and current policies, I trace how the ecologies, relations, and biological selves that make up pheasants have been shaped by hunting practices. I argue that, because of their ambiguous status derived from this hunting past and the changing nature of contemporary landscapes, pheasants are “unmade” and rendered elusive to conservation efforts. At the same time, pheasants have found ways to re-make themselves and make a living in modern landscapes — paradoxically, still in dialogue with hunters — which might be understood as a form of multi-species stewardship. In this way, pheasants defy labels such as wild, domestic, feral, or native, and shed light on how historically formed interdependencies continue to shape contemporary efforts at biodiversity and nature conservation in Anthropocene landscapes.

With all due respect, in the world of nature management he is seen as an inferior species; he does not matter. It’s the same for the real bird fanatics: for them the pheasant doesn’t count. He isn’t real. He has been walking around the Netherlands for two thousand years, but he isn’t real.

29 September 2023

Introduction

I am used to having encounters with pheasants. Especially where I grew up, close to the river floodplains, I would see them every day while walking our family dog. Sometimes I would spot one, usually a male, seemingly strolling casually through a field. On other occasions I was startled by a figure flying up from behind a blackberry bush, flapping noisily, accompanied by a shrill metallic crow. Female pheasants are camouflaged in shades of brown, contrasting with the spectacularly coloured cocks. Sunlight reveals their chestnut, golden-brown, dark green and red colouring, making them appear exotic and out of place. At the same time, these beautiful birds are bound to the landscapes of my childhood.

But the presence of pheasants and their appreciation in the Dutch landscape are far from self-evident. Pheasants are probably the most hunted bird species in the world.1 Active breeding, rearing, and releasing have been practiced for many “hunting animals”, but for none as long and as intensively as for the pheasant.2 Thanks to these practices, the pheasant is currently one of the most widely introduced birds worldwide.3 Pheasants have been bred, reared, and released for their meat and later for sport shooting/hunting. It is generally assumed that the pheasant was introduced to Western Europe by the Romans. Yet the first historical records of pheasants in the Netherlands appear in the fourteenth century in connection with medieval banquets. At the wedding feast of Duchess Katherine and Duke Edward in The Hague in 1369, six pheasants were served alongside 273 rabbits.

From the sixteenth century onwards, the breeding, rearing, and releasing of pheasants intensified.4 Hunting policies aimed to protect the species, such as bans on collecting eggs, destroying nests, or hunting for a few years after release. For example, in the province of Utrecht, protecting nests included a seven-metre radius restriction on mowing heather. After the French Revolution and subsequent changes in land ownership, when the role of the aristocracy in the Netherlands had somewhat diminished, pheasant hunting became more popular. From the second half of the eighteenth century, the pheasant became an important “hunting object” throughout Europe.5 Where pheasant hunting had once been an elite privilege, landowners now obtained the right to hunt them themselves.6 With more hunters, the systematic introduction of pheasants took off in the Netherlands. As a result, by the end of the nineteenth century, the birds were living independently throughout the country: “Originally introduced, but now living in a completely wild state in all provinces except Groningen and Drenthe”.7

In contrast to many other countries — such as the UK, where in 2016 up to forty-seven million birds were released and fifteen million shot8 — in the Netherlands it has been forbidden to rear and release pheasants since 1998. For the first time in a long co-evolving history, pheasants are seemingly left to become feral/wild. However, the centuries-long interdependency of pheasants and hunters still leaves its traces.

Scholars in the Environmental Humanities, Animal Geographies and related fields have paid close attention to the complex, entangled relations between human and nonhuman lives in shared landscapes.9 Whether using concepts of (actor-)networks, assemblages,10 topologies,11 meshworks,12 or hybridity,13 they all make the ontological claim that understanding the world involves dynamic relations between organisms and environments. By drawing attention to the complex entangled lives of humans, nonhumans, and landscapes, animal geographers (and others) have challenged binary assumptions, such as thinking in terms of strict human–animal14 and nature–culture15 divides. Recognizing these entanglements inevitably raises the question of what it means to be human in relation to animals — and highlights how animals actively figure in shaping their own lives and relations.

Despite this recognition, the dominant epistemologies through which we understand, treat, and envision the conservation of animals remain based on distinctions that reinforce purist views of organisms as species, breeds, and/or gene pools, tied to fixed and delineated places of belonging. Meanwhile, the historical geographies of human–animal relations are still often understood as a trajectory towards ever greater power and control.16 This perspective reaches its epitome in the era increasingly referred to as the Anthropocene, when animal lives have generally become more tightly controlled for human purposes; instrumentalized as commodities or intensively managed in the name of conservation. The story of the pheasant illustrates this development. Throughout history, pheasants have been relocated, bred, and reared for hunting. Yet to see these practices merely as expressions of human power, domination, and control risks upholding human exceptionalism as the sole driving force shaping landscape ecologies and nonhuman lives. Thus, it reaffirms what many argue is a major pitfall of using the term Anthropocene: the idea of humans as an all-powerful species that, as a single homogeneous unit, completely dominates “our” environment and all other beings that live there. By addressing pheasant becomings and exploring their genealogies in Dutch landscapes, this paper aims to tell a broader story. I take up Erica Fudge’s call to find ways to tell animal histories that help to “reconnect with our planet, and recognize ourselves as inseparable rather than special; reliant upon rather than dominating”.17 Instead of seeing hunting as only the act of killing to exert dominance over animal lives, what happens if we take seriously the ways in which hunters and pheasants historically influenced each other’s modes of existence? In what ways has — and perhaps still is — the relationship between pheasants and hunters a “becoming with”?18

In this article, I explore the shared histories of pheasants and hunters in the Netherlands, focusing on how pheasant becoming involves the agency of both pheasants and hunters. I ask how pheasants, hunters, and landscapes are “agential and active in the co-production of spatial relations”,19 by tracing the making, unmaking, and remaking of pheasants. This is important because pheasants bring into perspective more affirmative ways of envisioning Anthropocene landscapes for wildlife — that is how pheasants transition from being intensively bred to finding their own ways of becoming “wild”, and how they do so in relation to hunters. Through their historical interdependency with hunters, pheasants challenge neat labels like wild, domestic, feral, and native, and complicate our ideas of care and stewardship. They also show how formal efforts to conserve nature and biodiversity today are impacted by historically formed interdependencies. In the next section, I explore the theoretical and methodological implications of understanding animal histories and futures as processes of agential co-becoming. I then describe “making pheasant” as the historical process of rearing and releasing, how pheasants and knowledges about them are “unmade”, and how pheasants “remake” themselves in relation to hunters. I conclude by arguing that we might understand the relationship between pheasants, hunters, and the landscape as a form of multi-species stewardship.

Narrating Agential Animal Histories, Presents, and Futures

In the age of the Anthropocene, human–animal relations are often understood on a spectrum between full human control and wild animal self-making. Characterizing animals as domestic, wild, feral, native, or exotic not only sets up a simple wild–domestic dichotomy, it also inscribes an ideology of human mastery. Within this spectrum, the “domestic” animal is defined by its dependence on humans, while the “wild” animal is defined by its independence from them. Yet, as Anna Tsing writes: “Through such fantasies, domestics are condemned to life imprisonment and genetic standardisation, while wild species are ‘preserved’ in gene banks while their multi-species landscapes are destroyed”.20

Indeed, the wild–domestic interface creates powerful wildlife management strategies by assigning a legal status to animals depending on the spaces they occupy. For example, in rewilding schemes where large herbivores “de-domesticate” themselves and “rewild” the landscape,21 legal tensions arise around animal welfare and biosecurity, since their protection depends upon their being under human control.22 Similarly, conservation that aims to harness and promote free-living wildlife as ecological vectors in rewilding often involves intensive human management. Designating animals as “wild” does not necessarily serve them well, since it means that they become subject to wildlife management, which often involves large-scale killing.23 Arguably, legally labelling animals as wild, domestic, or feral can constrain certain becomings in ways that are harmful for the animals themselves. For example, Paul Keil traces how pigs in Australia have at various times been categorized as domestic, wild, and feral. He argues that such labelling has “un-made” their relational possibilities.24 At the same time, animal agencies may move outside legal human control by forging affective connections. As Maan Barua shows, calling parakeets “feral” inscribes them into regimes of biopolitical population control rooted in nativist ideas about who belongs where — even as the animals themselves create openings for alternative and more just shared worlds.25 But not all animals have an unambiguous legal status. For example, when animals receive protection as a threatened species “certain species’ lives are elevated to a political status, while the rest (initially at least, the unlisted) remain biological, or mere, life”.26 So while some animals enter biopolitical regimes when granted legal status as domestic, wild, or threatened, others remain “just” life — liminal and, perhaps to some extent, able to navigate in and out of the biopolitical realm.

How animals and the ways they are perceived are made and unmade happens alongside constantly evolving, reshaping, and adapting nonhuman agencies.

We are all secret agents, depending on the circumstances, waiting for another being who will give us new agencies, new ways of becoming agents, actively acted upon, undoing and redoing precarious selves (through) one another. This is, since the beginning of our time as living creatures, our history: a history that needs new stories, for these can be given a sequel.27

To move beyond the story of domestication as a unilateral mode of human control over “nature”,28 or the “wild” as untouched by human interference,29 we need alternative stories. Building on efforts to understand relationality through the new materialist (re)turn in Geography, I consider the pasts, presents, and futures of human–animal assemblages to consist of ongoing collaborations, interdependencies, and co-becomings of humans and animals. So “instead of being some thing, life forms are constantly evolving, constantly becoming, shifting in their composition”.30 This means that if “human nature is an interspecies relationship”,31 the same can be said for more-than-human natures. The notion of “species” therefore should not be taken to refer to fixed animal beings defined in terms of genotypes, static physical forms, or regular behavioural patterns, but rather to “ecologies of becomings”.32 When a species goes extinct, it is not the pure unit itself that we should mourn, but rather the loss of “vast intergenerational lineages, interwoven in rich patterns of co-becoming”.33

Becoming animal, however, entails more than interspecies interactions. The environment co-produces as well: “[O]n the one hand, the milieu ‘is taking’ the animal: it affects it, it captures it, it effectuates its power to be affected; on the other hand, the milieu does not exist outside the ‘grasping’ to which it is submitted: it exists through the way that a given animal confers on this milieu the power to affect it.”34 This means that the affordances the landscape provides for animals to thrive and survive35 are multilateral; what matters to animals within “sensory bubbles” or Umwelten is based not only on a species’ or subject’s perceptual lifeworld but also shared and co-produced by atmospheres.36 As such, landscapes are “overlapping projects of world-making”.37

Hunting forms a distinct genre in human–animal–landscape entanglements and becomings. The practice has been described as a cultural performance involving a close, personal engagement between hunter and animal.38 Hunters often speak of experiencing a certain state of being, a sense of becoming part of nature by actively attuning themselves to the animal. But hunters do not form a relationship with just any animal: “It must be a special sort of animal that is killed in a specific way for a particular reason”.39 What makes these animals “special” seems to be related to what Jamie Lorimer calls the “affective charisma” of conservation species, such as behaviour and physical appearance.40 Additionally, their cultural identity or status, as well as the moral justifiability of their death in terms of ecological balance or food provision, play a role in making an animal huntable.

Historically, the preservation and reservation of special animals for hunters can be understood as an early form of conservation.41 From their inception, Western conservation and management efforts, both at home and abroad, have been closely tied to hunting. The spatial relationships between hunter, animals, and the environment they inhabit — whether in Europe, North America, or elsewhere — are often framed as a form of care, identified as stewardship.42 This understanding has crystalized into management practices directed towards particular species.43 Aldo Leopold, a key figure in inspiring environmental stewardship with his land ethic, originally proposed that stewardship as wildlife management entails: (1) predator control (though he later opposed wolf hunting); (2) reserving game spaces; (3) artificially replenishing game species; and (4) habitat controls.44 However, Leopold’s initial ideas about wildlife management were not entirely new. Elite hunting traditions in Western Europe already involved appointing caretakers for such tasks. In Germany, this type of care is known as Hege, referring to caretakers’ practices such as feeding animals in enclosed spaces. The term encompasses both a type of space (Wildgehege) and an ethos of managing that space and the wildlife within it. When Leopold published his Sand County Almanac in 1949, he extended his notion of stewardship for particular game species to an ethic of care for nature as a whole, building on work in the emerging field of ecology.45 This understanding of nature as a system or complex process has had consequences for how the role of hunters in “nature” is viewed today: hunting for wildlife management and ecological stewardship are often assumed to go hand in hand.46 For example, in some cases, population control by hunters is seen as necessary to protect ecosystems from excessive pressure by certain wildlife populations.47 Yet, as Robert Holsman argues, seeing hunters as ecosystem stewards should not be considered self-evident: in relation to broader ecological objectives, hunters’ primary focus remains with the animals they hunt.

At the same time, the appropriation of space, related practices of care and particular hunting traditions are bond up with an elitist vision of exclusive land use, one that distinguishes hunting as desirable and legitimate from poaching, which is cast as unregulated and assumed to be unsustainable forest use by local communities. As such, stewardship has been critiqued for reaffirming human control and dominance over both human and animal lives. Stewardship, as it emerged from Christian theology, bestows upon humans both the privilege and the moral responsibility to take care of God’s creation.48 In this way, stewardship perpetuates an anthropocentric and Christian-humanist worldview in which huntable animals are objectified as natural resources. Especially in a North American context, it has also been seen to reflect a colonial, patriarchal ideology that is at odds with Indigenous perspectives.49

Despite these critiques, scholars have begun to embrace the multiple and often ambiguous meanings of stewardship, pointing to other ways it can be understood. Thus, Johan Peçanha Enqvist et al. identify care, knowledge, and agency as three dimensions that connect the discourse on stewardship in the academic literature: as an ethic, a motivation, an action, and an outcome. They argue that care is an underrepresented aspect in stewardship research, even though it can help us “identify and understand how more sustainable human–nature relationships can emerge and persist over time”.50 This also means that if we understand stewardship as an embodied and practiced expression of care, we should pay attention to the extent to which naturecultures51 foster interdependence, creativity, and other-than-human agencies and becomings — all while critically engaging with colonial and religious legacies.

The identities of hunters as stewards or caretakers can therefore be seen as co-produced by the animals they hunt, and vice-versa — perhaps modelled on the way flowers gain agency “through becoming enabled to make their companion pollinators be moved by them, and this is how the latter could themselves be agents, through becoming enabled to make the flowers able to attract them, and in turn to be moved by them”.52 We cannot draw one-to-one parallels between the bee–flower relation and that of hunter and pheasant, but it does appear relevant to consider the at least potentially processual, relational, and mutual — if not symmetrical — character of these practices of care.

To understand the shared histories of pheasants and hunters — and the ways in which, over centuries, pheasants have been “made” pheasant — I have conducted a review of Dutch hunting literature dating from 1895 until 1995. This includes a full review of all articles on pheasants published in De Jager (“The Hunter”, formerly De Nederlandse Jager), the official magazine of the Royal Dutch Hunters’ Association (formerly the KNJV), using the keywords “fazant” (pheasant), “haan/hen” (cock/hen), and “kweken” (rearing). I have also reviewed most Dutch hunting handbooks published in this period, focusing on how, historically, pheasant bodies and behaviours have been moved and shaped by hunters. To understand the contemporary situation of pheasants, I have also gathered data from more recent newspaper articles, policy documents, and websites of the Hunters’ Association and SOVON (Stichting Ornithologisch Veldonderzoek Nederland, the Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology). I have conducted several semi-structured interviews with hunters and exchanged emails and phone calls with SOVON, the FBE (Faunabeheereenheid, or Fauna Management Unit) Gelderland, and the Hunters’ Association. Even though these methods focus on written and spoken texts, the pheasant has always been present in this landscape — both in my daily bicycle rides to Wageningen and in countless field trips to estates and other hunting landscapes over the years.

Making Pheasants

There is no game species over which the hunter can exert as much influence as the pheasant. Mainly through artificial propagation, but also through feeding and protection. This “human connection” does not mean that pheasant hunting is in any way inferior to hunting other game. If that were so, generations of excellent hunters and game wardens here and elsewhere would never have concerned themselves with pheasants, for their interest was never in “chickens”.53

What a pheasant is and how they are envisioned has historically been shaped by this “human connection”. According to the above, what makes a pheasant a good game bird is their ability to respond to a variety of manipulations, including rearing and releasing. Even though these processes are very similar to the keeping of chickens, what sets pheasants apart is their ability to turn “wild” again. Thus, while for chickens, connections with humans are comparatively one-sided, in the case of pheasants, the “human connection” results not only from human manipulations but also from the ability of these animals to shape this connection themselves. Until the ban on releasing pheasants in 1998, pheasants in the Netherlands — as is still the case elsewhere — were highly manipulated into becoming huntable animals. In what follows, I will outline how the pheasant came to be a “perfect” huntable bird and how this has historically been enacted in relations with hunters as part of shared lifeworlds from the late nineteenth century through to the late twentieth century.

Rearing

At the end of the nineteenth century, the pheasant became a desirable game bird. With the decline of many other hunted birds (such as partridge) due to intensified agricultural land use, the ability of pheasants to adapt quickly to changing landscapes made them a blessing for hunters. Rearing pheasants was seen as the most effective way to secure a large huntable population within a relatively short time (one to two years). Because the entire process from rearing to release is time-consuming and costly, it was initially done mostly by elite landowners whose estates were large enough to hire a dedicated game keeper appointed with the task of breeding pheasants. The aim of rearing was to introduce and “civilize” (inburgeren) the pheasants within these private domains.54 Over time, however, this changed: in 1957, one hunter noted that he “no longer [considered the pheasant] the ‘elite bird’ it once was; one finds breeding flocks and sees attempts at rearing and release by owners of both large and small fields, in both guarded and unguarded hunts”.55

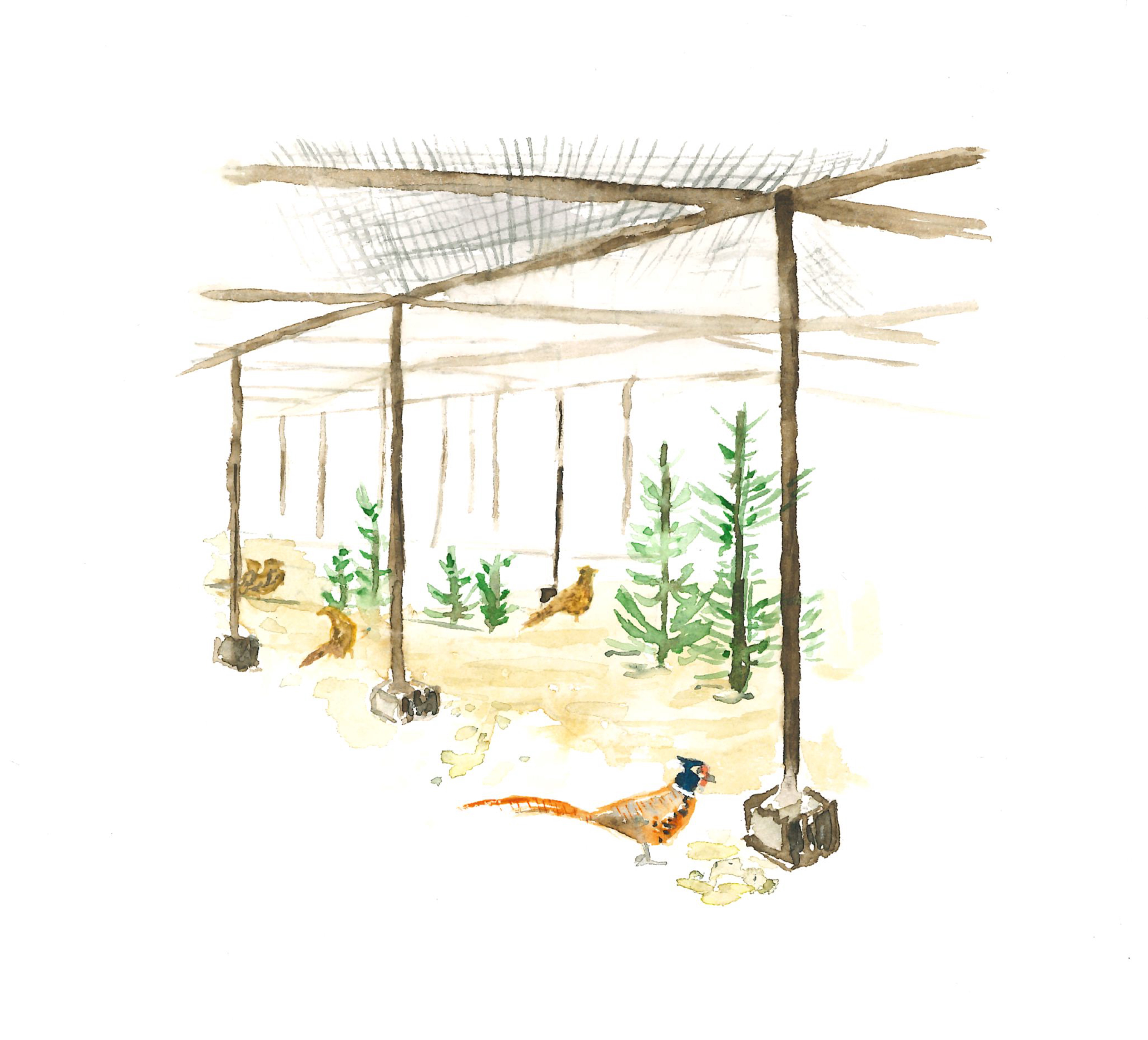

Pheasant chicks could be purchased at various ages (from one year old and older), or bred in enclosed pens, in so-called breeding groups (see figure 1). In these settings, the practice of captive rearing was legitimized by characterizing pheasant hens as poor mothers, incapable of raising many chicks on their own. In captivity, pheasant hens were considered “unreliable broody hens” (onvertrouwbare broedsters) because of their shyness towards humans.56 Wild pheasants were similarly considered “bad mothers”: “She lays her eggs carelessly in highly primitive nests, often in places that are plainly visible to all. Her way of brooding and caring for the young is likewise so careless and inadequate that, out of fifteen to eighteen eggs, she raises only four to seven young.”57 The writer concludes that “[a]ll these circumstances make it necessary to raise pheasants as young domestic poultry and in many cases the hen must be kept confined and her eggs hatched under a foster mother.”58

Fig. 1 Watercolour and pencil illustration of a pheasant breeding pen or “foktoom”, by the author.

Inspired by a drawing by Rien Poortvliet in A. H. M. Jurgens, Kennis en praktijk van de jacht op

waterwild, klein wild en schadelijk wild (1968), 101.

So, as soon as the pheasant hen had laid her eggs, they were removed to be hatched by someone else. Which bird would make the best foster mother for pheasant eggs was the subject of lively debate and experimentation. Various chicken breeds were suggested as surrogates. Bantam hens could hatch eleven to thirteen eggs, while larger black chickens might hatch up to twenty-one.59 Especially hunters who would rear a small number of pheasants made use of chickens. “Artificial mothers” (incubators) were also introduced, but not all hunters were in favour of this. Keeping pheasant chicks warm by a lamp, without social interaction from a living mother, was by some believed to produce inferior birds: “chicks raised under a lamp are neither wild nor tame, I would almost call them ‘ordinary’. “They respond differently, less personally”, while chicken-hatched chicks would exhibit similar behaviour to their surrogate mother: “with a calm hen, I get calm chicks”.60

Release

There are differing views on the best way to release pheasant chicks. Some authors suggest keeping the chicks in a large coop until they are eight weeks old before releasing them in the forest. Others advise releasing them younger, at around four weeks, under the care of a turkey hen. Turkeys are considered too heavy and “careless” to hatch pheasant eggs, but they are praised as excellent nannies. According to an article in the Revue der Sporten from 1909, four-week-old chicks could be brought into a remote forested area with their turkey foster mother, who would fiercely defend “her” chicks from predators if a dog or a cat slipped past the gun of a forester or game keeper. She would also teach the chicks to forage for food and roost with them high up in the trees. Once the chicks could take care of themselves, the turkey hen would leave them and “return home” (komt naar huis terug).61 Others recommended releasing the chicks at ten to twelve weeks, once they could “stand on their own feet” (op eigen benen kunnen staan).62

Ultimately, the aim of releasing was to “rewild”63 or make wild (verwilderen) the pheasant chicks, which means that the pheasants have to learn how to navigate the landscape and behave as true game birds during the hunt. Several factors are considered important. Pheasants are described as having a “natural tendency to roam” (aangeboren trekdrang),64 meaning that they move away in search of better living conditions if their place of dwelling is lacking. Landowners therefore tried to motivate pheasants to stay within their hunting grounds, given the effort and expense invested in raising them. A. H. M. Jurgens recommends gradually releasing small groups of pheasants from a coop in a forested area, feeding them in the same place every day. So long as some pheasants are still inside the coop, the rest are unlikely to stray far. Once all of them have been released, the daily feeding routine would teach the birds to view the forest as a safe haven — ideal for roosting in trees and feeding at specific times. In this way, pheasants “know the way, as it were, and easily return to the place of release in autumn” (kennen zij als het ware de weg en keren in het najaar gemakkelijker naar de plaats waar zij zijn uitgezet terug). Thus, releasing pheasants in the forest helps to manipulate and predict their behaviour, ensuring that they are “where the hunter wants them” (waar de jager hen wil hebben) when hunting season comes around.65 This might explain why, even though — as I will explain later — pheasants do not necessarily exclusively inhabit forests, hunting literature often refers to them as “forest pheasants”.

Hunting

In pheasant hunting, the place where the hunter wants the pheasant to be is related to the flight behaviour of the bird and the method of hunting. This is peculiar, as pheasants are taxonomically classified as a ground bird (Ratites): “They are good on their feet and can, if they wish, outpace almost any other fowl; but they fly poorly and do so only when absolutely necessary”.66 Nevertheless, hunters prize pheasants for their flight: they can reach speeds of up to 95 km/h (59 mph) and “their method of flying requires powerful wingbeats, producing a flapping sound, especially when taking flight; but once the pheasant has reached a certain height, it flutters little and shoots forward rapidly in a downward glide with outstretched wings and tail, as if on an inclined plane”.67

Pheasants were traditionally trapped or hunted with falcons, but with the advent of firearms, they became popular quarry for shooting. In the UK, this type of hunting even developed into its own practice known simply as “shooting”. This practice is all about manipulating and predicting the flight behaviour of the bird. As such, the “poor” flying skills of the pheasant make it an excellent game bird for shooting. Antonius Hermans described the essence of shooting as “the art of bringing them up, over, and down”.68

“Bringing them up” means flushing the pheasants into the air. In every hunting method, pheasants are startled into flight. This can be done by a dog flushing birds from cover, while a single or a small group of hunters follow behind. In driven shoots, so-called “beaters” walk through the landscape, systematically driving birds toward waiting hunters. Ideally, throughout the drive (drift), individual pheasants should be continuously made to fly up.

“Bringing them over” means manipulating the birds so that they “present themselves” in the appropriate way. In general, high flying pheasants are desired. According to J. Antonisse, the best conditions for high flying pheasants are created in driven shoots: “this really gives the game the opportunity to show its worth”, and, he adds, “the same goes for the guns”.69 To achieve this, a pheasant must: (a) be in prime condition; (b) be flushed at the right moment; (c) have clear space to gain height easily; (d) have a target cover to aim for; and (e) be able to spot the guns in time once airborne, and attempt to soar over them.70 Evidently, the landscape plays an important role in producing high flying birds. Ideally, pheasants fly over open ground between coverts, making them accessible targets. Pheasants tend to look for cover in places they are familiar with, and this knowledge allows hunters to predict flight paths. As such, the landscape is much more than a backdrop to the hunting scene; it plays an active role in the process of becoming a huntable pheasant — and in the knowledge and skills required to be a good hunter.

Finally, “bringing them down” is about the skill of the shot. Hunters who shoot pheasants while they are still flying low are frowned upon and considered to go against the hunter’s ethos. Instead, pheasants should be allowed time to climb and pick up speed. Meanwhile, birds that refuse or fail to climb are dismissed as “flutterers” (flodderaars). During the hunt, hunters are referred to as “the guns”. They are expected to be able to distinguish cocks from hens, as the latter must often be spared.

Naturalizing Pheasants

The sparing of hens suggests that hunters were keen to encourage natural breeding, rather than having to rely on rearing and release. Indeed, at various times pheasants have lived all across the Netherlands in a fully wild state. In many cases, rearing and release were intended as a starting point from which pheasants would (re-establish) wild populations: “these semi-wild pheasants sometimes voluntarily leave the forests in which they were hatched and raised, to settle independently, live entirely wild all year round, breed, multiply, and form colonies that can survive without human help”.71 The process was literally referred to as inburgeren — “naturalization”, in the sense of granting citizenship to the hunting field.

This naturalization was, however, actively encouraged by hunters. Various measures were taken to ensure annual repopulation of wild pheasants within the hunting grounds. First, the environmental conditions had to be right. To this end, extensive knowledge exchange took place in the hunting literature about the pheasants’ preferred habitat. This literature sees the pheasant as “a cross between forest-fowl [woudhoen] and field-fowl [veldhoen], needing both woods and open country to thrive. It needs the flat field, which in summer offers a desirable place to stay with good cover and more abundant food, and the forest, which provides shelter in the winter and the roosting places overnight”.72 This suggests that pheasants are not “tied to any particular type of landscape but feel equally at home in polders, forests, or dunes”.73 Second, when the environmental conditions were favourable, hunters took further measures to support existing populations of wild pheasants. One such was the creation of so-called “wild pheasantries”. These were areas planted with trees and scrubs, where tame males were introduced to attract hens and where the birds would be fed and protected from predators, both by the physical layout and the active culling of predators in an around these preserves. Another common practice, likely centuries old, was to protect pheasants from harsh winters by catching and keeping them in an attic or coop until spring, when they were released to breed.74 This was especially popular on estates.75 Not everyone approved, however: at the turn of the twentieth century, one hunter argued against providing winter shelter: “He [the pheasant] gladly makes use of it, which softens him up, to his own detriment and that of the landowner. By nature, the pheasant is a hardy bird”.76

The pheasant’s “nature” and genetic disposition were actively experimented upon. Despite pheasants’ adaptability to a variety of landscape types, some hunters believed not all pheasants were equally suited to every biotope. Jurgens distinguishes three kinds of pheasant in 1968: (1) “forest pheasants” (boschfazanten), smaller birds whose cocks lack the white neck ring and who “do” best in low-lying terrain; (2) “Mongolian” or “Formosa” pheasants, also known as “ringnecks”, which are larger and do have a white neck ring. These were introduced to Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and are better suited to higher ground;77 and (3) “Tenebrosus” pheasants, which are dark birds, thought to be a spontaneous mutation of the “forest pheasants” originating in England in 1888. These are the author’s favourite. He believes they fly better, taste better, are “definitely better mothers” (beslist betere moeders), and they do well in his hunting grounds which are marshy with reeds and willows.78

With the introduction of these different breeds and their supposed variety of characteristics in terms of behaviour, appearance, and biotope choice, ensuring breed purity became of interest. Especially outside the Netherlands, pheasants were carefully bred to maintain a pure stock. The Dutch literature shows a slight preference for “pure” strains, but no real effort seem to have been taken to keep them so — all varieties could interbreed and produce fertile offspring, meaning that wild pheasants would all inevitably become “bastards”. Yet this “impurity” was not necessarily always considered a downside: crossbreeds were usually considered “strong, fertile, and well adapted to their environment”.79 Accordingly, becoming a naturalized pheasant in the Netherlands also meant becoming a genetic hybrid, adapted and attuned to landscapes informed by its ancestral lineage as a hunting animal.

The ability to naturalize and to turn “wild” also gave pheasants a liminal legal status between domestic and wild. Arguably, a hand-reared pheasant could be classed as livestock, but once released they would become wild game animals. If recaptured alive, for example to be kept in an attic during a cold winter, they would revert to livestock again. In the UK, where rearing and releasing still occur, this legal grey area works in favour of the hunting elite, since only animals classified as wild may legitimately be hunted. The ambivalent nature of the pheasant highlights a political and legal tension between the wild and the domestic, as George Monbiot wryly remarks: “the pheasant’s properties of metamorphosis should be a rich field of study for biologists: even the Greek myths mentioned no animal that mutated so often”.80

As this section has shown, the “human connection” between pheasants and hunters has historically been characterized by elaborate manipulations to create perfect huntable birds and by shaping landscapes in which they can be brought “up, over and down”. And it is this historical connection that entangles pheasants in processes of unmaking, as the next section will show.

Unmaking Pheasants

Thanks to the use of arguments that are not always entirely fair — yet eagerly listened to in our anti-hunting society — we now live in an era in which the release of pheasants is banned. There are even many activists who openly state that they would not regret it at all if the pheasant were to disappear completely from the Netherlands, as this would be a neat way to get rid of a troublesome exotic species.81

The ban on rearing and releasing pheasants, introduced in 1998, exposed conflicting values. Naturalists regarded the bird as exotic, while hunters worried that pheasants were being driven to extinction for precisely that reason. Although pheasants are classed as naturally occurring wild bird species under the Dutch Birds Directive, to this day “many bird watchers don’t really take the pheasant seriously. They see the bird as an exotic descendant of captive-bred birds that were released en masse for hunting well into the last century, and as a hybrid — a mix of various subspecies and variants from their original range, from the Balkans eastward deep into Asia”.82 Understanding pheasants as exotic frames them as out of place in the Netherlands, and their presumed hybridity renders them unnatural. As exotic and hybrid birds, their state of being and place of belonging are denaturalized. This delegitimization can be understood as the legacy of a biotic nativism that is deeply embedded in nature management.83 While it may appear to be just the view of a handful of birding enthusiasts, this perspective deprives pheasants of value and interest, which, in turn, can influence policymaking. Information about the conservation status of pheasants in the Netherlands is based on counts by volunteer bird watchers, coordinated and assessed by SOVON, the Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology. This organization has the aim to track the numbers and distribution of birds in the country. The results of SOVON’s counts inform nature policy and management. This means that policy effectively depends on information gathered by people who may have little interest in pheasants: for some counters, the pheasant quite literally does not count. Since the affective relationships produced through counting practices are “a crucial element of knowing as well as managing wild animals”,84 pheasants, as underappreciated birds in the world of birding, seem to occupy a blind spot.

SOVON do still report on the conservation status of pheasants in the Netherlands. According to SOVON, pheasant populations are not doing well. Whether an animal population has a sustainable future in the Netherlands is determined in a so-called staat van instandhouding (conservation status). This assessment considers the animal’s distribution, population size, habitat (quality and extent), and future prospects. In 2022, SOVON assessed the conservation status of pheasants as “moderately unfavourable” (matig ongunstig).85 According to their 2023 report, “the species is generally unable to sustain itself independently”. That the pheasant population might eventually settle into small regional groups is considered “plausible, but not certain” (aannemelijk, maar niet zeker).86 Seemingly, the hunter-pheasant connection makes it difficult to define whether they live in a natural state: “Due to the strong human influence on the population in the past, but also now in the border regions and probably also locally, there is probably no question of a natural situation”.87 The report also notes that some illegal releasing still occurs. Paradoxically, current understandings of how pheasants are faring reproduce a “politics of purity”88 in which their naturalness and wildness are defined by their distance from humans — a wildness untainted by hunters. Meanwhile, to minimize pressure on the remaining population, the national bird protection organization Vogelbescherming advocates a total ban on pheasant hunting.

Unmaking is a “process that disregards how being exists through interactions with others”.89 Arguably, interactions between hunters and pheasants — from their historical introduction to the more recent introduction of sub-species by hunters — have rendered them exotic and hybrid. Because of their association with hunters, pheasants are “unmade” into unnatural beings. As a result, they are not seen as charismatic or even relevant conservation species in the Netherlands. This low status is probably best understood in relation to the species they are emphatically not: partridges. Partridges share a very similar history. They too have been kept, bred, and released for hunting, supposedly even since Roman times. Unlike pheasants, however, partridges are regarded as native. Due to rapidly declining numbers from intensive farming, hunting partridges was banned in 1998. Today, specialists count and register partridges and in some areas also ring them for monitoring. Subsidies are provided to nature organizations to create landscapes specifically for partridges. Pheasants benefit indirectly from these landscape changes, but there are no subsidies specifically for enhancing pheasant habitats, nor are they monitored in the same way. In the Netherlands, pheasants now largely slip through the net of formal conservation efforts.

While the historical and ongoing interactions with hunters make pheasants uninteresting as conservation subjects, hunters themselves are arguably caught up in this process of unmaking as well. For example, they are excluded from formal knowledge production based on population counts. Even though hunters have been counting pheasants for years, their methods have so far been deemed invalid. As Jamie Lorimer and Steve Hinchliffe have shown in the case of corncrakes, counting and surveillance methods shape which lives become visible that allow for political representation.90 This may explain why the Hunters’ Association (Jagersvereniging) is now lobbying for an official, standardized counting protocol for both hunters and bird watchers, to be recognized by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). This can be seen as a strategy to prevent a total ban on pheasant hunting and to legitimize hunting by providing accountable data. Such efforts illustrate how hunters, too, are delegitimized as advocates for pheasants. Their extensive historical and ongoing relations with pheasants render them unsuited to “speak for” pheasants. In this sense, hunters’ knowledge and motivations are “unmade” too.

Pheasants’ liminal status between wild and domestic, as well as their association with hunters, keep them from being fully integrated into formal conservation efforts. Whereas, historically, rearing and release can be considered a form of intense bio-control — including procedures of classification, monitoring, ordering, spatial confinement, and restraint — pheasants are now less politicized and scientized than other targets of conservation. Compared to other “alien species”, pheasants seem to occupy a unique position. They were not introduced as an “ecological tool” for managing biosecurity,91 nor are they viewed as a biosecurity threat. They are not seen as rewilders of novel ecosystems or as indicator species for one, unlike, for example, partridges. As such, the ways in which pheasant lives have become culturally and spatially entangled with the rural biology of the Dutch landscape remains largely unexamined.

Remaking Pheasants

In what has widely come to be referred to as the Anthropocene, hunting appears as one of the many forms of violence against the nonhuman world, especially when it is not deemed necessary for subsistence in a Western context. At the same time, scholars have turned their attention to non-Western communities for insights into alternative, more sustainable and less destructive ontologies, in which hunting plays an important role in understanding human–nonhuman relationality.92 The process of unmaking described above can be understood as a process in which “lively entanglements are unwound”.93 The entanglements of pheasants with hunters render pheasants “not real” (as quoted in the epigraph to this article) and disqualify them from serious consideration as a conservation species. While hunting in Western contexts might be considered a one-sided act of domination — especially when elite hunters combine taking animal lives with claiming control over land — at the same time this risks rendering animals as mere passive subjects of total control and also obscures human–pheasant relationality. Therefore, to understand and evaluate the character of the pheasants and the type of interaction with the hunters, we can also consider how lively entanglements are “re-wound” or re-made, as part of an ongoing, ever-changing and situated relationship between hunters and pheasants.

Since the ban on rearing, releasing, and supplementary feeding of pheasants of 1998, their numbers have declined sharply. Whereas pheasants were once widespread across the country, they have now vanished from many areas. For example, pheasantries in sandy, forested areas kept populations stable, but as soon as these were abandoned, ironically enough, the ‘forest-pheasant’ disappeared from these landscapes as well as from hunters’ language. Pheasants began to move away from their assigned spaces towards “beastly places”94 of their choosing, where they could come into their own and breed on their own terms. At the same time, the dynamics shaping pheasant populations, distribution, and behaviour have also changed due to major landscape transformations. Pheasants depend on a wide variety of foods, including berries, grasses, buds, insects, and crop residue, but with the intensification of agriculture, lowering water tables and growing urbanization, food availability has decreased. These landscape changes have also increased predation pressure, especially from foxes, due to reduced cover. This means that not only have the conditions for pheasants’ survival in the Dutch landscape changed over time, but so too have hunters’ tactics for killing and/or caring for them. Pheasants and hunters are now entering into a new relationship in which hunters are far more reliant on pheasant agency and less focused on controlling them.

We can assume that the pheasant has been naturalized in Western Europe for more than two thousand years. Due to its cleverness and physical strength, it has been able to maintain itself effortlessly, has not introduced any foreign diseases, has not driven away or exterminated other bird species, and is always a feast for the eyes (including the quietly brown-yellow hens), while the cock’s metallic call adds a fascinating element to the landscape.95

Hunters have long celebrated the pheasant’s resilience and beauty, and have adapted landscapes for them for centuries — a practice that continues to this day. Many scholars now suggest we should appreciate the adaptive abilities of animals as “Anthropocene heroes” in novel ecosystems, by highlighting how spaces are shaped by multispecies encounters and proliferation rather than fixed sets of species.96 At the same time, this also means recognizing that humans are not only destroyers of landscapes, but also, at times “increase rather than decrease biodiversity, or at the very least allow for different kinds of biodiversity to emerge and thrive”.97 In these landscapes, pheasant agencies, to quote Despret, emerge not only as the ability to “make others do things” but also to “incite, inspire, or ask them to do things” in various ways.98

First, pheasants appear to have changed the way they are hunted and appreciated. The grand driven shoots of the past required large populations, but with fewer birds now spread across various landscapes, dedicated pheasant shoots no longer take place. Today, pheasants are part of a varied tableau of small game taken during small-scale flushing hunts — but only in places where pheasants remain relatively abundant. In many other hunting grounds, pheasants have become animals not to hunt: “In the past, pheasants were shot, but if you see one here now, don’t shoot — they’re rare.”99 Whether pheasants are considered huntable thus depends on their presence or absence in particular landscapes. Arguably, pheasants now partly determine their own huntability through their spatial dispersal and declining numbers.

Second, pheasants turn hunters into landscape managers. “The pheasant […] requires careful management to ensure the conservation of the species”.100 While in a conservation context the spatial relations between hunters and the animals they hunt are often understood in terms of regulating populations through hunting, in the case of pheasants “hunters bring attention to preventing mowing losses [by protecting nests], they create game crops, and manage corvids and foxes”.101 Hunters intervene in intensively farmed landscapes by providing small strips of cover or food for wildlife — but only with the landowner’s permission. In this way, hunters act as caretakers of pheasant habitats and spatial advocates for pheasant lives. Even though Robert Holsman argues that hunters could be better ecosystem stewards,102 the care hunters give to pheasants can be seen as precisely the kind of interdependency and co-becoming that matters when it comes to affording forms of pheasant agency. For pheasants seem to “incite, inspire or ask”103 hunters to change landscapes and take protective measures. These affective practices create opportunities to accommodate pheasants while at the same time pheasants themselves choose where they want to live — with or without the help of hunters. In this sense, hunter–pheasant interdependencies turn hunters, at least partly, into (landscape) managers, living alongside pheasants in “a mutual composition of worlds”.104

If we take seriously the ways in which pheasants make hunters do things, then stewardship cannot be understood as a solely human endeavour, one that in this case would rest exclusively in the hands of the hunter. Building on — but also moving beyond — their history as charismatic flyers to be shot, pheasants have become stewards of their own lives and landscapes, where they negotiate management with hunters. Rather than simply casting hunters as ecological stewards, perhaps we might see the wider range of practices that maintain pheasant ecologies and landscapes as a form of multi-species stewardship. Multi-species stewardship, as a mode of caring for animal lives and landscapes, is co-shaped by pheasant presences and absences, behaviours and shared histories that create — or re-make — possibilities for pheasants to thrive and live unfettered lives. These historically evolved ways of being are embedded in a wider landscape that shapes which possibilities emerge: a reared pheasant or a wild pheasant, a pheasant living in the dunes or the floodplains — each might enact its pheasantness differently.105

Conclusion

This article has shown that through processes of making, unmaking, and remaking, becoming pheasant is a multispecies affair. This is especially clear in view of their history as hunted animals. Bred and raised by chickens and turkeys, cared for and released to be shot by humans, pheasants are now choosing their own habitats, which are subsequently cared for by hunters to cater to their needs. Clearly, the bird’s hunting history still plays a role in its absence from policy making, expert interest, and management today. Meanwhile, pheasants are carving out a place for themselves as open-field dwellers and as attentive mothers, adapting to the Dutch landscape through a multispecies negotiation with hunters. As such, the ongoing adaptations of pheasants to changing landscapes have inevitably reshaped both their behaviour and geographies, as well as hunter–pheasant interdependencies over time.

From a broader spatio-temporal perspective, becoming pheasant is not a linear passage from wild to domestic to feral, but rather a complex and dynamic trajectory in which pheasant knowledge, adaptive fitness, and “naturalness” are renegotiated over time and in specific places together with hunters. Thus, pheasants disrupt simple categories such as wild, domestic, feral and native — which arguably makes them elusive as conservation targets. At the same time, pheasants complicate our understanding of human–animal relations in the Anthropocene. For example, while the domestication of chickens — and their fossilized bones as a geological marker — is considered the ultimate symbol of the Anthropocene,106 pheasants have coexisted with humans since long before chickens were domesticated. Research shows that eight thousand years ago in China, pheasants were drawn to human settlements by food, eventually forming interdependent relationships.107 Yet because this human connection never altered their genetic makeup, pheasants are not formally considered domesticated. Unlike chickens, then, pheasants have developed an interdependency with hunters while remaining “wild”. Thus, pheasants complicate not only the categorization of human–animal interdependencies themselves, but also our understanding of how these relationships are formed.

The ways in which pheasants become with hunters is not simply a story of one-sided domination: pheasants have long been caught up in performances108 as hunting animals, co-producers of a multispecies management, and resilient birds able to secure a state of wildness, determined by the opportunities for autonomy and self-determination.109 Pheasants show that stewardship need not be understood as a solely human-driven affair; in a relational world, care practices emerge through complex inter- and intra-actions between hunters, pheasants, and landscapes based on shared histories. I argue that we might understand these relationships as a form of multispecies stewardship which brings a more-than-human perspective to conservation efforts and debates. In this sense, the Dutch pheasant complicates our understanding of what it means to be wildlife in the contemporary landscapes of the Anthropocene — and challenges us to ask when which animals are conserved, how, and by whom.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and insightful comments. I am also grateful to the editor and copyeditor of Humanimalia for their thorough edits, which have enhanced the clarity and readability of this article. This article was written as part of the PhD project “Hunting Landscapes”, funded by the Wageningen School of Social Sciences (WASS), whose support is gratefully acknowledged.

Notes

See Hill and Robertson, The Pheasant, 123–36.

de Rijk, Vogels en mensen, 79.

Fuller and Garson, Pheasants, 2. See also Errington and Gewertz, “Pheasant Capitalism”.

See De Rijk, Vogels en mensen, 79.

ten Den, Achtergronden en oorzaken, 13.

This transition from connecting the hunting right to ownership of the land did not go smoothly. See Bruneel and Wessels, “Verenigd maar verdeeld”.

“Oorspronkelijk geplant, maar thans in volkomen wilden staat levende in alle provincies, behalve Groningen en Drente”. Albarda, Aves Neerlandicae, 61. Unless otherwise specified, all translations are by the author.

Aebischer, “Fifty-Year Trends”, 6.

Philo and Wilbert, Animal Spaces, Beastly Places.

Gibbs et al., “Camel Country”; Gorman, “Therapeutic landscapes”.

Whatmore and Thorne, “Wild(er)ness”.

Ingold, Being Alive, 63.

Whatmore, Hybrid Geographies.

Plumwood, “Politics of Reason”.

Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture.

Tuan, Dominance and Affection, 7.

Fudge, “History of Animals”, 262.

Haraway, When Species Meet, 150.

Miele and Bear, “More-Than-Human Research Methodologies”, 229.

Tsing, “Unruly Edges,” 144.

Lorimer and Driessen, “Bovine Biopolitics”.

Lorimer, Wildlife in the Anthropocene, 97–117.

Kaufman and Mallory, The Last Extinction.

Keil, “Unmaking the Feral”.

Barua, “Feral Ecologies”.

Braverman, “The Regulatory Life”, 20.

Despret, “Secret Agents”, 44.

Lien, Becoming Salmon; Swanson et al. Domestication Gone Wild.

Cronon, “Trouble with Wilderness”.

Greenhough, “Vitalist Geographies”, 38; original emphasis.

Tsing, quoted in Haraway, When Species Meet, 19.

Lorimer, Wildlife in the Anthropocene, 7.

Van Dooren, Flight Ways, 12.

Despret, “Secret Agents”, 38.

Gibson, “Theory of Affordances”.

Uexküll, Umwelt und Innenwelt; van Heijgen et al. “Landscape Is a Trap”.

Tsing, “Dream of the Stag”, 14.

Marvin, “A Passionate Pursuit”, 46–60.

Cartmill, View to a Death, 29.

Lorimer, “Nonhuman Charisma”.

Taylor, American Conservation.

Von Essen and Allen, “Killing with Kindness”, 183.

Holsman, “Goodwill Hunting?”.

Gigliotti et al. “Changing Culture of Wildlife”, 79.

Mathevet et. al., “Concept of Stewardship”.

Holsman, “Goodwill Hunting?”.

Van Heijgen et al. “Haunted by Hunting”.

Callicott, Thinking Like a Planet, 167.

Eichler and Baumeister, “Hunting for Justice”; Luke, “Violent Love”.

Enqvist et al., “Stewardship as a Boundary Object”, 26.

Latimer and Miele, “Naturecultures?”.

Despret, “Secret Agents”, 40.

“Er is geen wildsoort waarop de jager zo’n invloed kan uitoefenen als de fazant voornamelijk door de kunstmatige vermeerdering, maar ook wel door het voeren en de bescherming in het algemeen Deze ‘mensverbondenheid’ betekent niet dat de jacht op fazanten onder hoeft te doen voor die op enig ander wild Ware het anders dan zouden generaties van voortreffelijke jagers en jachtopzichters zich hier en elders niet met fazanten hebben opgehouden, want naar ‘kippen’ ging hun belangstelling niet uit.” Cartouche, “Fazanten”, 813. Quoted in Dahles, Mannen in het groen, 209.

Fürst, “Het inburgeren van den fazant”, 1.

“Het is niet meer de ‘élite-vogel’ van vroeger; men treft foktomen aan en ziet broeden uitzetpogingen bij bezitters van grote en kleine velden, in bewaakte- en onbewaakte jachten.” Cartouche, “ITBON”, 104.

Ericus, “Jachtsport”, 438.

“De Wilde fazantenhen is een slechte moeder. Zij legt haar eieren op zorgelooze wijze in hoogst primitieve nesten, op plaatsen, die ieder gemakkelijk in ’t oog vallen. Haar manier van broeden en de jongen verzorgen is eveneens zoo zorgeloos en onvolkomen, dat zij, van 15 tot 18 eieren, slechts 4 tot 7 jongen groot brengt.” G., “Engelsche Fazanterieën”, 1.

“Al deze omstandigheden zijn oorzaak van de noodzakelijkheid, om de fazanten als jong tam plumvee op te kweeken en in tal van gevallen moet men de hen op-gesloten houden en de eieren, die zij legt, door een pleegmoeder laten uitbroeden.” G., “Engelsche Fazanterieën”, 1.

Jurgens, Kennis en praktijk , 103.

“Ze reageren anders, minder persoonlijk. […] [B]ij een rustige kloek heb ik rustige kuikens. De kuikens onder de lamp zijn noch wild, noch rustig; ik zou haast zeggen, ‘gewoon’.” Zandhaas, “Betekent het uitzetten”, 236.

Ericus, “Jachtsport”, 439.

Jurgens, Kennis en praktijk, 109.

Not to be confused with the discourse of “rewilding” landscapes through (re)introduction of keystone species to promote ecological processes. Here it refers to the process by which individual animals such as pheasants are “made” wild again.

Jurgens, Kennis en praktijk, 93.

Jurgens, Kennis en praktijk, 109.

“Zij zijn goed ter been en kunnen, als zij willen, in het hardloopen bijna met ieder ander Hoen wedijveren; zij vliegen echter slecht en doen dit daarom slechts in den uitersten nood.” Kalsbeek, Fazant, pauw, kalkoen en parelhoen, 2.

“Hun wijze van vliegen vereischt krachtige vleugelslagen en gaat daarom vooral bij het opvliegen met een klappered geluid gepaard; wanneer echter de Fazant eens een zekere hoogte bereikt heeft, fladdert hij weinig, maar schiet met uitgespreide vleugels en staart als van een hellend vlak in benedenwaartsche richting snel vooruit.” Kalsbeek, Fazant, pauw, kalkoen, 2.

Hermans, Jagerswoordenboek, 104.

“Hierbij krijgt dit wild pas echt goed de kans te laten zien wat het waard is. Overigens geldt dit evenzeer voor de geweren.” Antonisse, De jacht in Nederland, 133.

Antonisse, De jacht in Nederland, 133.

“Intusschen verlaten deze halfwilde fazanten somstijds vrijwillig de bosschen, waarin zij uitgebroed en opgegroeid zijn, gaan zich zelfstandig vestigen, leven het geheele jaar door volkomen in den wilden staat, telen voort, vermenigvuldigenn zich en vormen koloniën, die zonder hulp van den mensch kunnen bestaan.” Kalsbeek, Fazant, pauw, kalkoen, 6.

“De fazant nu staat tusschen deze twee groepen in: hij houdt het midden tusschen woud- en veldhoenders en heeft voor zijn gedijen behoefte zoo- wel aan bosch als aan vlak. Hij heeft het vlakke veld noodig, dat hem in den zomer een gewenscht verblijf met goede dekking en rijkelijker voedsel biedt, en bosch, dat hem beschut in den winter en hem gelegenheid schenkt, ’s avonds te boomen en er den nacht door te brengen.” Fürst, “Het inburgeren van den fazant”, 1.

Dam, Jagen, 56.

Kalsbeek, Fazant, pauw, kalkoen, 6.

De Rijk, Vogels en mensen, 79.

“Hij maakt er evenwel gaarne gebruik van, hetgeen hem tot zijn eigen schade, en die van den jachteigenaar, verweekelijkt. Van nature is de fazant een harde vogel.” G., “Engelsche Fazanterieën”, 1.

Jurgens, Kennis en praktijk , 95.

Jurgens, Kennis en praktijk, 97.

Antonisse, De jacht in Nederland, 133.

Monbiot, “The Shooting Party”.

“Dankzij het gebruik van lang niet altijd zuivere argumenten — waarnaar in onze antijachtmaatschappij zo gretig wordt geluisterd — leven wij thans in het tijdperk van het verbod op het uitzetten van fazanten. Er zijn zelfs legio aktievoerders die er rond vooruitkomen dat zij het geenszins zouden betreuren wanneer de fazant geheel uit Nederland verdween, omdat dat het een mooie opruiming van de storende exoot zou vormen.” Huygen, “De overbodige fazant,” 539.

“Veel vogelaars nemen de fazant niet echt serieus. Ze beschouwen de vogel als een exoot, nazaat van gefokte vogels die tot ver in de vorige eeuw massaal werden uitgezet als jachtwild. Een bastaard, bovendien, een mix van diverse ondersoorten en varianten uit hun oorspronkelijke woongebied, van de Balkan oostwaarts tot ver in Azië.” Urlings, “Mens en Natuur”.

Barua, “Feral Ecologies”.

Boonman-Berson, Rethinking Wildlife Management, 3.

SOVON, “Staat van instandhouding”, 2.

SOVON, “Factsheet Fazant”, 5.

SOVON, “Factsheet Fazant”, 5.

Rutherford, “The Anthropocene’s Animal?”, 216.

Keil, “Unmaking the Feral”, 20.

Lorimer, “Counting Corncrakes”; Hinchliffe, “Reconstituting Nature Conservation”.

Buller, “Introducing Aliens”, 184.

See Ingold, Hunting and Gathering; Nadasdy, “Gift in the Animal”.

Frederiksen, “Haunting”, 533; cf. Rose, “Angel of History”, 77.

See Philo and Wilbert, Animal Spaces, Beastly Places.

“Wij mogen er van uitgaan dat de fazant dus in West-Europa al meer dan 2000 jaar is ingeburgerd. Hij heeft zich door zijn slimheid en lichamelijke sterkte moeiteloos kunnen handhaven, heeft geen vreemde ziektes binnengebracht, geen andere vogelsoorten verdreven of uitgeroeid en is steeds een lust voor het oog (ook de stemmig bruingeel gekleurde hennen), terwijl de metalige roep van de haan een boeiend element aan het landschap toevoegt.” Huygen, “De overbodige fazant”, 539.

See Palmer et al. “Hybrid Apes”.

Rutherford, “The Anthropocene’s Animal?”, 218.

Despret, “Secret Agents”, 40.

Interview with hunter, 18 August 2023.

“De fazant […] vraagt een zorgvuldig beheer om de instandhouding van de soort te waarborgen.” Koninklijke Nederlandse Jagersvereniging, “Fazant”.

“Hierbij geven jagers aandacht aan het voorkomen van maaiverliezen, leggen ze wildakkers aan, beheren ze kraaiachtigen en vossen.” Koninklijke Nederlandse Jagersvereniging, “Fazant”.

Holsman, “Goodwill Hunting?”, 814.

Despret, “Secret Agents”, 40.

Barua, “Feral Ecologies”, 911.

Tsing, “The Dream of the Stag”.

Bennett et al., “How Chickens Became”.

Barton et al., “The Earliest Farmers”.

Whatmore and Thorne, “Wild(ern)ness,” 438.

Collard et al., “Manifesto for Abundant Futures”.

Works Cited

Aebischer, N. J. “Fifty-Year Trends in UK Hunting Bags of Birds and Mammals, and Calibrated Estimation of National Bag Size, Using GWCT’s National Gamebag Census.” European Journal of Wildlife Research 65, no. 4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-019-1299-x.

Albarda, Johan Herman. Aves Neerlandicae: Naamlijst van Nederlandsche Vogels. Leeuwarden: Meijer & Schaafsma, 1897.

Antonisse, J. De jacht in Nederland. Amsterdam: Becht, 1970.

Barton, Loukas, Brittany Bingham, Krithivasan Sankaranarayanan, Cara Monroe, Ariane Thomas, and Brian M. Kemp. “The Earliest Farmers of Northwest China Exploited Grain-Fed Pheasants Not Chickens.” Scientific Reports 10 (2020): 2556. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59316-5.

Barua, Maan. “Feral Ecologies: The Making of Postcolonial Nature in London.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 28, no. 3 (2022): 896–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.13653.

Bennett, Carys, Jan Zalasiewicz, Mark Williams, and Richard Thomas. “How Chickens Became the Ultimate Symbol of the Anthropocene.” The Conversation, 12 December 2018. https://theconversation.com/how-chickens-became-the-ultimate-symbol-of-the-anthropocene-108559.

Benson, Etienne. “Animal Writes: Historiography, Disciplinarity, and the Animal Trace.” In Making Animal Meaning, edited by Linda Kalof and Georgina M. Montgomery, 3–16. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2011.

Boonman-Berson, Susan. “Rethinking Wildlife Management: Living with Wild Animals.” PhD Diss., Wageningen University, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18174/455279.

Braverman, Irus. “The Regulatory Life of Threatened Species Lists.” In Animals, Biopolitics, Law: Lively Legalities, edited by Irus Braverman, 19–37. London: Routledge, 2015.

Bruneel, Dieter, and Leon Wessels. “Verenigd maar verdeeld: Constitutionele debatten over jacht en eigendom in het Verenigd Koninkrijk der Nederlanden.” BMGN: Low Countries Historical Review 134, no. 4 (2019): 4–32. https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.10760.

Buller, Henry. “Introducing Aliens, Reintroducing Natives: A Conflict of Interest for Biosecurity?” In Biosecurity: The Socio-Politics of Invasive Species and Infectious Diseases, edited by Andrew Dobson, Kezia Barker, and Sarah L. Taylor, 183–98. London: Routledge, 2013.

Callicott, J. Baird. Thinking Like a Planet: The Land Ethic and the Earth Ethic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Cartmill, Matt. A View to a Death in the Morning: Hunting and Nature through History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Cartouche. “ITBON-wildonderzoek: Fazanten.” De Nederlandse Jager 62, no. 7 (1957): 104.

Cartouche. “Fazanten.” De Nederlandse Jager 84, no. 23 (1979): 813.

Collard, Rosemary-Claire, Jessica Dempsey, and Juanita Sundberg. “A Manifesto for Abundant Futures.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 105, no. 2 (2015): 322–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.973007.

Cronon, William. “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Environmental History 1, no. 1 (1996): 7–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/3985059.

Dahles, Heidi. Mannen in het groen. De wereld van de jacht in Nederland. Nijmegen: SUN, 1990.

Dam, J. H. Jagen. Bussum: C. A. J. van Dishoeck, 1962.

ten Den, P. G. A. Achtergronden en oorzaken van de recente aantalsontwikkeling van de fazant in Nederland. Arnhem: Rijksinstituut voor Natuurbeheer, 1989.

Descola, Philippe. Beyond Nature and Culture. Translated by Janet Lloyd. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Despret, Vinciane. “From Secret Agents to Interagency.” History and Theory 52, no. 4 (2013): 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/hith.10686.

Eichler, Lauren, and David Baumeister. “Hunting for Justice: An Indigenous Critique of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.” Environment and Society 9, no.1 (2018): 75–90. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2018.090106.

Enqvist, Johan Peçanha, Simon West, Vanessa A. Masterson, L. Jamila Haider, Uno Svedin, and Maria Tengö. “Stewardship as a Boundary Object for Sustainability Research: Linking Care, Knowledge and Agency.” Landscape and Urban Planning 179 (2018): 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.07.005.

Ericus. “Jachtsport: Fazanten (Hoe men ze in den zomer ‘poot’).” De Revue der Sporten 3, no. 28 (1909): 436–39.https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=dts:1664028:mpeg21.

Errington, Frederick, and Deborah Gewertz. “Pheasant Capitalism: Auditing South Dakota’s State Bird.” American Ethnologist 42, no. 3 (2015): 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12137.

Frederiksen, Aurora. “Haunting, Ruination and Encounter in the Ordinary Anthropocene: Storying the Return of Florida’s Wild Flamingos.” Cultural Geographies 28, no. 3 (2021): 531–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/14744740211003650.

Fry, Tom, Agnese Marino, and Sahil Nijhawan. “‘Killing with Care’: Locating Ethical Congruence in Multispecies Political Ecology.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 21, no. 2 (2022): 226–46. https://doi.org/10.14288/acme.v21i2.2054.

Fudge, Erica. “The History of Animals in the Present Moment: Rumination 2.0.” Humanimalia 13, no. 1 (2022): 253–64. https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.11282.

Fuller, Richard. A., and Peter. J. Garson, eds. Pheasants: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan 2000–2004. Gland: IUCN, 2000. https://iucn.org/resources/publication/pheasants-status-survey-and-conservation-action-plan-2000-2004.

Fürst. “Het inburgeren van den fazant in de vrije wildbaan.” De Nederlandse Jager 1, no 28 (1896): 1.

G., “Engelsche Fazanterieën.” De Nederlandse Jager 4, no. 44 (1899): 1–2.

Gibbs, Leah, Jennifer Atchison, and Ingereth Macfarlane. “Camel Country: Assemblage, Belonging and Scale in Invasive Species Geographies.” Geoforum 58 (2015): 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.10.013.

Gibson, James J. “The Theory of Affordances (1979).” In The People, Place, and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, William Mangold, Cindi Katz, Setha Low, and Susan Saegert, 56–60. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Gigliotti, Larry M., Duane L. Shroufe, and Scott Gurtin. “The Changing Culture of Wildlife Management.” In Wildlife and Society: The Science of Human Dimensions, edited by Michael J. Manfredo, Jerry J. Vaske, Perry J. Brown, Daniel J. Decker, and Esther A. Duke, 75–89. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2009.

Gorman, Richard. “Therapeutic Landscapes and Non-Human Animals: The Roles and Contested Positions of Animals within Care Farming Assemblages.” Social & Cultural Geography 18, no. 3 (2017): 315–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2016.1180424.

Greenhough, Beth. “Vitalist Geographies: Life and the More-Than-Human.” In Taking-Place: Non-Representational Theories and Geography. Edited by Ben Anderson and Paul Harrison, 37–54. London: Routledge, 2016.

Haraway, Donna. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

van Heijgen, Eugenie, Clemens Driessen, and Esther Turnhout. “The Landscape Is a Trap: Duck Decoys as Multispecies Atmospheres of Deception and Betrayal.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 49, no. 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12629.

van Heijgen, Eugenie, Esther Turnhout, and Clemens Driessen. “Haunted by Hunting: A Landscape Genealogy of the Biopolitics, Necropolitics, and Sovereign Power of Red Deer and Wild Boar Management at the Veluwe.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 8, no.1 (2025): 431–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486241301251.

Hermans, A. G. J. Jagerswoordenboek Schiedam: Roelants, 1947.

Hill, David and Peter A. Robertson. The Pheasant: Ecology, Management and Conservation. Oxford: BSP Professional, 1988.

Hinchliffe, Steve. “Reconstituting Nature Conservation: Towards a Careful Political Ecology.” Geoforum 39, no. 1 (2008): 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.09.007.

Holsman, Robert H. “Goodwill Hunting? Exploring the Role of Hunters as Ecosystem Stewards.” Wildlife Society Bulletin 28, no. 4 (2000): 808–16.

Huygen, Will. “De overbodige fazant.” De Nederlandse Jager 98, no, 15 (1993): 539.

Ingold, Tim. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London: Routledge, 2011.

Ingold, Tim. “Hunting and Gathering as Ways of Perceiving the Environment.” In Redefining Nature: Ecology, Culture, and Domestication, edited by Roy Ellen and Katsuyoshi Fukui, 117–55. London: Routledge, 2020.

Jurgens, A.H.M. Kennis en praktijk van de jacht op waterwild, klein wild en schadelijk wild. Amersfoort: Roelofs van Goor, 1968.

Kalsbeek, G. Fazant, pauw, kalkoen en parelhoen: Geïllustreerd handboekje voor de verzorging en verpleging van deze siervogels. Zutphen: Schillemans & van Belkum, 1902.

Kaufman, Les, and Kenneth Mallory, eds. The Last Extinction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993.

Keil, Paul G. “Unmaking the Feral: The Shifting Relationship between Domestic-Wild Pigs and Settler Australians.” Environmental Humanities 15, no. 2 (2023): 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-10422267.

Koninklijke Nederlandse Jagersvereniging. “Fazant.” De Jagersvereniging, accessed 25 April 2024. https://www.jagersvereniging.nl/jagen/diersoorten/fazant/.

Latimer, Joanna, and Mara Miele. “Naturecultures? Science, Affect and the Non-Human.” Theory, Culture & Society 30, nos. 7–8 (2013): 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413502088.

Leopold, Aldo. “The Conservation Ethic.” Journal of Forestry 31, no. 6 (1933): 634–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/jof/31.6.634.

Lien, Marianne E. Becoming Salmon: Aquaculture and the Domestication of a Fish. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015.

Lorimer, Jamie. “Nonhuman Charisma.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 25, no. 5 (2007): 911–32. https://doi.org/10.1068/d71j.

Lorimer, Jamie. “Counting Corncrakes: The Affective Science of the UK Corncrake Census.” Social Studies of Science 38, no. 3 (2008): 377–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312707084396.

Lorimer, Jamie. Wildlife in the Anthropocene: Conservation after Nature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Lorimer, Jamie, and Clemens Driessen. “Bovine Biopolitics and the Promise of Monsters in the Rewilding of Heck Cattle.” Geoforum 48 (2013): 249–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.09.002.

Luke, Brian. ““Violent Love: Hunting, Heterosexuality, and the Erotics of Men’s Predation.” Feminist Studies 24, no. 3 (1998): 627–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178583.

Mathevet, Raphaël, François Bousquet, and Christopher M. Raymond. “The Concept of Stewardship in Sustainability Science and Conservation Biology.” Biological Conservation 217 (2018): 363–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.015.

Marvin, Garry. “A Passionate Pursuit: Foxhunting as Performance.” The Sociological Review 51 (2003): 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00450.x.

Miele, Mara, and Christopher Bear. “More-Than-Human Research Methodologies.” In Key Methods in Geography, 4th ed, edited by Nicholas Clifford, Megan Cope, and Thomas Gillespie, 229–44. London: SAGE Publications, 2023.

Monbiot, George. “The Shooting Party,” Monbiot, 28 April 2014. https://www.monbiot.com/2014/04/28/the-shooting-party/

Nadasdy, Paul. “The Gift in the Animal: The Ontology of Hunting and Human-Animal Sociality.” American Ethnologist 34, no. 1 (2007): 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2007.34.1.25.

Palmer, Alexandra, Volker Sommer, and Josephine Nadezda Msindai. “Hybrid Apes in the Anthropocene: Burden or Asset for Conservation?” People and Nature 3, no. 3 (2021): 573–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10214.

Philo, Chris, and Chris Wilbert, eds. Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human–Animal Relations. London: Routledge, 2004.

Plumwood, Val. “The Politics of Reason: Towards a Feminist Logic.” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 71, no. 4 (1993): 436–62.

Redmalm, David. “Holy Bonsai Wolves: Chihuahuas and the Paris Hilton Syndrome.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 17, no. 1 (2014): 93–109.

de Rijk, Jan Hendrik. “Vogels en mensen in Nederland 1500–1920.” PhD Diss. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 2015.

Rose, Deborah Bird. “What If the Angel of History Were a Dog?” Cultural Studies Review 12, no. 1 (2006): 67–78. https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v12i1.3414.