Leonine Visibility and the Production of Nature

Humanimalia 15.1 (Fall 2024)

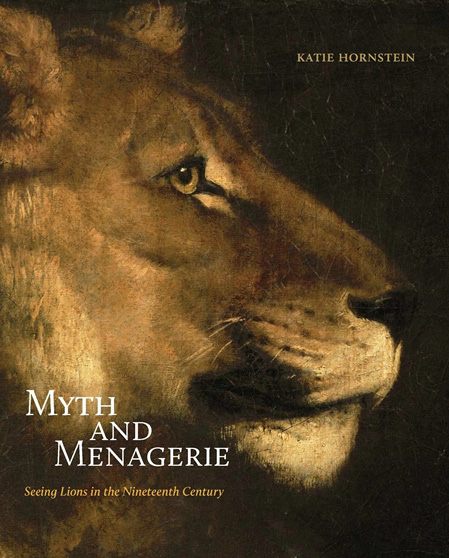

I wept as I finished reading Katie Hornstein’s magnificent new book, Myth and Menagerie: Seeing Lions in the Nineteenth Century. Admittedly, I do cry easily, but the way that Hornstein engaged me in this fascinating and deeply tragic story of human–lion relations is truly devastating. Most readers will know all too well that research in animal studies often involves studying awful things that societies have done, and continue to do, to animals. But Hornstein’s book is particularly affecting because she makes central the stories of individual lions who were brutally captured and killed by the French during their Algerian campaign (1830–1903). The lived experiences of these lions, from their seizure and traumatic voyages to Paris, to the miserable situations in which they were exhibited for artists and curious onlookers, as well as their sadly premature deaths, forms the core of the book. Hornstein’s meticulously researched exploration of the fates of numerous lions — hunted to extinction in North Africa, looted as war trophies, hailed as proof of colonial masculine power, exploited as abused objects of public entertainment for private profit — carries a deep emotional charge, the power of which is further underscored by her transparency about the role that personal loss and grief played in the writing of the book.

Hornstein lays out the fundamentals of her argument with admirable clarity in the book’s Introduction. Organizing the contents in roughly chronological order, she begins with the establishment of the Muséum d’histoire naturelle in Paris in 1794 and ends in the decades after 1900 with the extinction of the Barbary lion in North Africa. As she writes, this timeframe “implies a depressing paradox about the production of ‘nature’ in the nineteenth century that haunts every chapter of this book” (11). Namely that “the practice of looking at captive animals in urban, cosmopolitan contexts, as well as the proliferation of visual images of lions […] cannot be disentangled from the fact of their disappearance in the wild” (11).

What differentiates Hornstein’s approach from previous studies of nineteenth-century representations of animals is her exploration of the role lions played as artists’ models, figures of public dissection, and as taxidermic specimens. Building on John Berger’s comparison of the viewer’s experience in art galleries and in zoos, and his provocative observation that the way we see caged animals in the zoo is “always wrong”,1 Hornstein argues for a “shared set of viewing practices between the cage and the frame by locating works of art as a dynamic point of convergence between these two spaces” (10). Hornstein supports this method of viewership by considering diverse visual media, providing readers with insights into both the formally structured milieu of nineteenth-century French artistic production and more popular forms of cultural production including mass-produced prints and the newly invented medium of photography. The book is richly illustrated with exceptionally high-quality colour reproductions so that Hornstein’s incisive discussions of specific paintings, drawings, and sculptures are amply supported. Further, many of these images are not well known, and thus Hornstein is to be thanked for drawing the viewer’s attention to these works, many of which are startlingly beautiful.

The first chapter explores how French artists broke with long-established hierarchies in French academic painting, using well-known lions as models for paintings that were formative in the construction of identity in postrevolutionary France. The chapter begins by focusing on a remarkably fecund and famous family of lions that lived in the state menagerie from 1798 through the first decade of the nineteenth century. The lions, Mark and Constantine, had several litters of cubs, some of whom survived. Hornstein reveals how artistic representations of the female lion, Constantine, fashioned her into an exemplary model of the postrevolutionary mother. This leonine family were depicted in numerous “scientific” studies in oil on vellum by Nicolas Maréchal, whose paintings were then bound in leather and used primarily by contemporary scientists to advance their understanding of big cats. The fact that these renderings of the skin and fur of lions were painted on another animal’s skin, then collected and bound in the skin of yet another animal seems worthy of some consideration, however brief, and I found myself wishing that Hornstein had delved into this intriguing mash-up of animal bodies.

The chapter continues with a discussion of Jean-Baptiste Huet’s unusually large painting of Mark and Constantine, entitled A Family of Lions in Their Cage (shown in the Salon of 1802). Hornstein interprets the painting as a political statement based on Huet’s emphasis on the animals’ caged setting. Such commentary was traditionally reserved for artists committed to the lofty practice of History Painting, a category that included classical, biblical, mythological, and historical subjects with an emphasis on the composition of human figures in space. Hornstein’s intriguing proposal is that Huet was attempting to fuse the lower ranked art of animal painting with History Painting to make a “properly historical animal painting” (52). Thus, according to Hornstein, Huet’s incarcerated lions could be seen to refer to the revival of slavery under the postrevolutionary French government, or to invoke the “specter of the revolutionary prison as a site of exemplary trauma” (41). Hornstein’s rich analysis of this painting, along with other representations of Mark and Constantine, illuminates how two famous lions were rendered and shaped to constitute political ideas and ideals at a moment when the French republic was struggling to forge a new identity. As the author makes clear, the role of lions in France’s political self-formation was critical.

The second chapter begins with a detailed description of the various lions that were already in Paris as the nineteenth century began, and those that were sent or donated to the official menagerie in the following decades. Included among these was a lion given to the republic by a Jewish-Algerian merchant named Michel Busnach

to whom the French government owed seven million francs. Busnach’s gift of a lion, according to Hornstein, “must be regarded as both boldly suggestive and fabulously ambiguous” (56). Busnach was not French or Christian, and his identity as Other became so inextricably connected with the lioness he donated that administrators of the Muséum d’histoire naturelle did all they could to reject his gift. Despite these efforts, the lioness entered the collection where she served as a model for such important romantic artists as Eugène Delacroix, Antoine-Louis Bayre, and Théodore Géricault. It is well known that lions were a common subject for romantic artists, but Hornstein’s extensive research reveals how deeply engaged these artists were in studying lions, both living and dead, describing the complex avenues they used to gain access to their animal subjects. The strongest section of this chapter is the author’s discussion of Géricault’s astonishingly beautiful painting, Head of a

Lioness (c. 1819–20). Hornstein suggests that the likely model for this under-discussed masterpiece was Busnach’s unwanted lioness and she connects the lioness’s problematic status and identity with Géricault’s “larger preoccupation with the instability of power” (63). In addition, she situates the production of the Head of a Lioness within the artist’s biography, noting that it was probably completed during the period of his convalescence from a mental health crisis triggered by the mixed reception of his 1819 entry to the Salon, The Raft of the Medusa. The second half of the chapter focuses primarily on Delacroix’s numerous paintings and drawings of lions and lionesses and the diverse kinds of animal models he used. In addition to direct study of living lions in the Muséum d’histoire naturelle, Delacroix eagerly attended dissections of lions that died at the menagerie, and he studied taxidermized lions as well. Hornstein’s fascinating discussion finds that Delacroix’s representations of lions were not only the result of direct observation, but that their extraordinary ferocity was the result of the artist’s creative reanimation, because the lions he had access to were either in various states of torpor, dead, or skinned, mounted and preserved.

The third chapter offers a masterclass in how to combine art historical and animal studies methods to create a rich and nuanced context for a single work of art. Focusing on Antoine-Louis Barye’s life-size sculpture, Lion Attacking a Snake (first shown in plaster in 1832, then in bronze in 1835), Hornstein situates the sculpture within contemporary discussions of relational viewership. In nineteenth-century Paris one could see lions wasting away in the public menagerie and compare the living lions with painted and sculpted renderings of them exhibited in the official salon. In some instances, the paintings were viewed as inferior to the actual animals, but the reception of Barye’s sculpture was so enthusiastic that the menagerie’s lions were seen as a pitiful disappointment in comparison. An art critic writing in Le Charivari called the living, captive lions “slaves, without animation, without rage, without force.”2 Hornstein writes that “Just as the lions at the menagerie were subject to being viewed through the lens of artworks, so too were works of lion-centered art susceptible to being evaluated through the actual living, breathing animals to whom they referred” (109). For Barye, studying actual lions, especially when they were feeding, gave him some understanding of their behaviour in the wild, but his sculpture of a lion viciously attacking a snake was primarily a product of his imagination given the pathetic condition of the living and dead lions he could observe. Hornstein explores how Barye’s imaginary drama challenged an academic tradition that dictated that only human figures could convey powerful emotions and meaning. Barye’s sculpture aggressively asserted that animal bodies could be of equal importance and that they should share the same status as representations of the human form.

In Chapter Four, Hornstein examines lion hunts and explores how the visual theme and cultural practice of hunting lions became emblematic of French colonial expansion in North Africa. I was stunned to read about just how many big cats were exported to France from Algeria in the years immediately after the conquest. “In 1838 and 1839,” Hornstein writes, “the French government reported that a staggering 5,448 lions, hyenas, and panthers were exported […]. For the year 1840, this number rose to 7,970 […] living and killed animals” (133). In addition to sending animals to Paris, the French offered bounties for lions, panthers, and hyenas in Algeria. Much like efforts to eradicate wolves during the settlement of the western United States, the French argued that a large-scale destruction of animals would help indigenous peoples whose livestock were endangered by predators. In reality, the eradication of indigenous animals functioned as a proxy for the pacification and eradication of indigenous people. French colonialists enthusiastically embraced the opportunity to hunt and kill big cats (and plenty of other animals), driving Barbary lions to extinction in less than one hundred years. Profit and status were conferred on the most successful practitioners of this culture of violence, and Hornstein traces the stories of two famous lion hunters and the objects of material and visual culture that helped amplify their status as celebrities, including reproductive engravings, photographs, and an extraordinarily odd late painting by Édouard Manet. Hornstein’s focus here is on differentiating the meaning conveyed by actual lion hunts from representations of them. She finds that for nineteenth-century French viewers these signified two very different things. Iconographically, the hunt continued to serve as a traditional image of masculine heroism, but actual lion hunts did something very different: they helped create clear divisions between humans and animals and reinforced the concept of human exceptionalism at a moment when questions about man’s place in nature was being problematized.

In the final chapter, Myth and Menagerie moves away from the respectability of the natural history museum to the seedier world of the circus, where artists, including Rosa Bonheur and Edwin Landseer, became acquainted with lion tamers and studied the lions they used in their performances. Bonheur, the most successful and famous animal painter of her time in France, was even presented with two lion cubs by a lion tamer, and she kept the surviving female named Fatma in her private menagerie outside Paris. Hornstein contrasts Bonheur’s lioness with another Fatma — a boulevard entertainer purportedly from Tunisia — whose “orientalizing” erotic desirability and unattainability resembles the powerful human compulsion to touch and interact with lions. Hornstein explores how late nineteenth century photos and paintings of women with lions exploited the fantasy of a relationship “characterized by possession and domination over another living creature” (173). The author follows a trail that leads from the wish to interact with lions to its capitalist fulfilment in private circuses run by celebrity lion tamers. Here, the author takes readers to coarser sites and more brutal sights, and in doing so investigates “an entire network of relationships among circuses and their related spectacles, the possession and domination of lions, and the production of works of art” (178). Hornstein explores the newly invented medium of photography and efforts by early practitioners to capture images of humans interacting with lions. In some photos lion tamers were posed with taxidermic lion bodies producing inadvertently comedic results, while plans for carefully composed photographs of human performers with live leonine stage props were usually derailed by cats acting like cats. Invariably these modern images cannot and do not measure up to long-established romantic vision of lions found in painting and sculpture.

Finally, in her Afterword, Hornstein pulls her wide-ranging and thoughtfully researched study together to consider the fate of these lions, whose “availability as figures of representation simultaneously marks an impending absence” (214). Interest in animal studies is growing rapidly among art historians, and Hornstein’s book should be required reading for anyone considering such a move. The text is beautifully written, incorporating all the relevant methodological and theoretical references without becoming bogged down with jargon. Further, as with all good art history, Hornstein’s insightful formal analyses open up the images, while her thorough research contextualizes them, so that the reader is left with a fuller understanding of the meaning of these images for those who made them and the audiences for whom they were initially produced. But, most importantly, the lives of actual lions — both the captives brought to a foreign land, and those who remained behind and were massacred — remains central to the text. Among its many strengths, I believe the author’s greatest achievement is to maintain her vigilant focus on the tragic lives of these animals, and it is this focus that brought this reader to tears.

Notes

John Berger, About Looking (New York: Pantheon, 1980), 23.

“Ils sont là, dans leur cages, esclaves, sans animation, sans colère, sans force.” Jacques Arago, “Beaux-arts: Salon de 1836”, Gazette des théatres: Journal des comédiens, April 17, 1836, 459. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k63365344/f3.