Recentring the Animal in Multispecies Ethnography

Humanimalia 14.2 (Spring 2024)

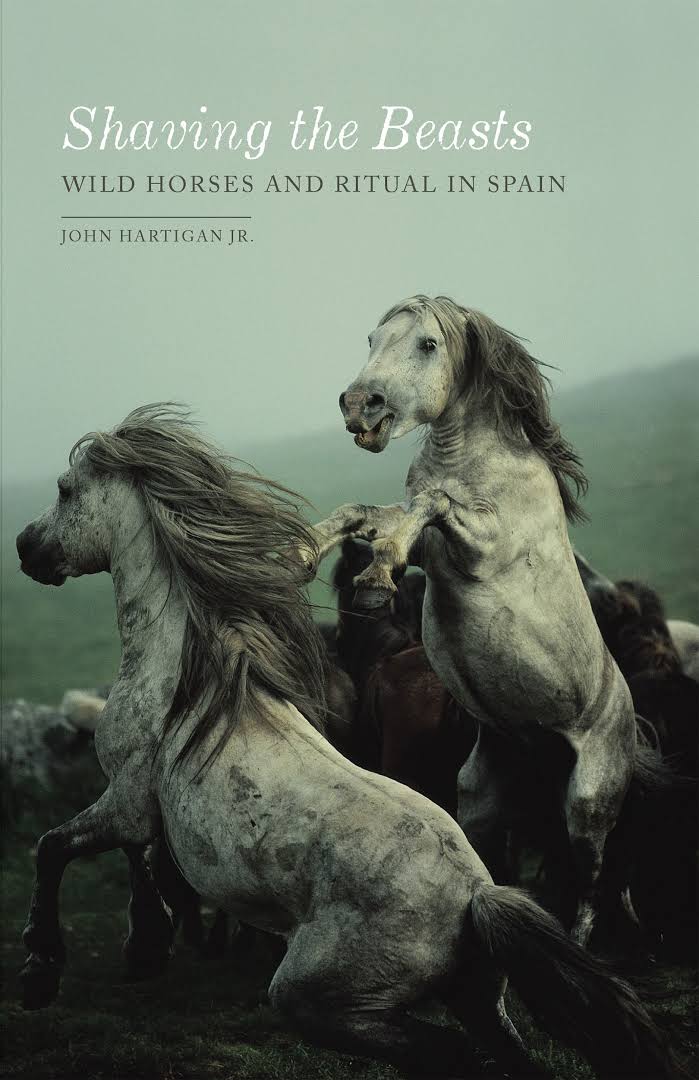

I first encountered the research project that grew into this book when it was an early work in progress. The author, John Hartigan Jr., was a generous mentor during my graduate studies, and in that spirit he invited me along to a seminar discussion and workshop of his project proposal — one that was mutually exciting, in that he was also looking for “horse people” to help him shape his approach to studying the sociality of horses during a festival called a rapa des bestas (“shaving the beasts”). This summertime practice unfolds in the mountains of Galicia, wherein several hundred wild-living horses are driven down from the mountains into enclosures, or curros, where the hair from their manes and tails is shaved off and male foals are culled from the herd. After a matter of an afternoon or a matter of days, depending on the town holding the rapa, the shaved horses are released back into the mountains. Hartigan had attended this event as an interested spectator the prior summer, and had decided to go on to develop a full ethnographic study of the horses during the following summer’s event. Hartigan’s work-in-progress presentation included a number of photos of the event he had visited, showing hundreds of horses who normally live very unenclosed lives penned up into a small corral and surrounded by rowdy human spectators. So, seated at a seminar table with a very illustrious and (to me!) intimidating set of senior scholars debating the ins and outs of new forms of multispecies ethnography emerging in the mid-2010s, the only confident footing I had at this moment was grounded in the “horse person” side of me.

As a horse person who had spent countless hours with horses since childhood, negotiating power and relationships with them, managing their pain and discomfort in veterinary and other challenging contexts and so on and so forth, some things that were obvious to me in the images of the rapa were not visible to the discussants. My first concern was that it was not immediately clear to me that the acute equine miserableness of this setting was fully visible to the discussants. As neither an ethnographer nor ethologist, I had no epistemological or academic claim to this observation. But looking at the rolling eyes, high heads, open mouths and pressed-in bodies filling the frames of the photos, I wondered about the immediacy of the horses’ experiences inside of the corral and how methodological innovation would work in their favour. If one key purpose of multispecies ethnography is to try to get out from under the primacy of humanism, then what would this study do for horses?

Looking back on this now, many years later, I can better understand this point of friction. Multispecies ethnography is fundamentally connective: as a methodology, it produces a complex and illuminating map of how individual species are always intersecting with intricately entwined webs of life and flows of power. Looking up and around at any given moment of study is the point; keeping a broad, rather than super-focused, point of view is in large part what drives the novel insights that arise from this form of inquiry. Thus, the tendency not to dwell on the situation in the corral. Multispecies ethnography also does not necessarily depend on a deep knowledge of the individual species themselves in question — particularly undomesticated species — in order to clarify key points about their existences that otherwise might not be visible from species-specific points of view. In fact, as Hartigan himself notes, “cultural anthropologists are generally loathe to draw on or deploy scientific frameworks” in part because “ethnographers are not disposed to make authoritative knowledge claims” (257–8). Multispecies ethnography is trying to get at relationships rather than individuation, dwelling in situatedness and specificity rather than generalizability. As Hartigan notes, in some cases this manifests as direct resistance to dominant paradigms, primarily in the sciences, that have systematically avoided, ignored, or even downright rejected relational understandings of human and nonhuman beings. In this way, multispecies ethnography is a profoundly useful ecological approach to uncovering cultures that are asymptotic to human worlds and understanding how culture works beyond the human, sometimes at the intended and even productive expense of ontological species-specific knowledge.

But horses, as primarily domesticated and well-known animals, were somewhat complicating this calculus: it seemed risky to undertake this project without attending to existing knowledge about horses-as-horses. It seemed to me that interpretations of the events shown during the workshop that might be basic to many horse people were at risk of being missed or made slant. The methodological conversations around the table were not quite getting at this gap. If horse people could explain several elements of what was happening in the rapa, then would the conclusions from this project speak only to other ethnographers? Would it be able to also provide insights to people whose daily lives are entwined with horses themselves — people whose own lives, and the lives of the horses they relate to, can stand to benefit from the broader ways of thinking and clarity of vision that multispecies ethnography as a whole can provide, but have heretofore on the whole been talked past rather than addressed by the field? Ask any day-to-day practical horseperson what their thoughts are on multispecies ethnography (and often, to be fair, equine ethology) and you are not likely to get an enthused or well-versed answer. There was no doubt that this project would certainly be able to contribute meaningfully to the growing literature about multispecies ethnographic methods in a way that ethology could not; it would contribute to a deeper cultural understanding of the rapa des bestas than a classic anthropocentric ethnography could. But would it be possible to craft an ethnography that would be able contribute something to our collective understanding of horses that horse people themselves could not?

My short, emphatic answer to this question is: yes. In fact, it is this book’s most hard-won achievement. In this text, Hartigan wades headlong into a thicket of methodological and practical tensions, and emerges with novel and sometimes troubling insights that are relevant for a range of humans whose lives intersect with horses and nonhumans more broadly: horse people, animal people, human–animal studies researchers, nonhuman animal welfare advocates, ethnographers, and ethologists alike will all find themselves the recipients of important interventions in these pages that have the potential to improve equine lives.

Readers of Hartigan’s prior work will not be surprised to find methodological rigour and ingenuity in these pages. Shaving the Beasts is the second book in his “multispecies trilogy”, following Care of the Species: Races of Corn and the Science of Plant Biodiversity (2017).1 The trilogy as a whole seeks to expand the development and application of social theory beyond the confines of human society. Care of the Species is an extended ethnography of botanists and plant breeders in Mexico and Spain that includes the iconic chapter “How to Interview a Plant”, in which Hartigan posits an innovative “how-to” (and “why-to”) guide for rendering nonhumans as ethnographic subjects. It is a groundbreaking book for thinking through how contemporary ethnographers can productively relate to science, scientific knowledge, and scientific thinking.

Shaving the Beasts picks up a key theme from this plant work. In studying any nonhuman species, he argues in this book’s conclusion, “ethnographers pursuing multispecies subjects” need to decide “how or whether to tap scientific expertise in developing our accounts and analyses of animals” (257). Care of the Species made the case that ethnographers could and should productively engage, rather than sidestep, scientific epistemologies as part of their work alongside constituting nonhumans as valid ethnographic subjects. In Shaving the Beasts, Hartigan shows this ethos at work when turning his lens towards horses. Unlike many plants, horses are a social species, and ethology has a place in understanding that sociality. So not only does Hartigan recognize horses as ethnographic subjects, but in focusing on their sociality as the focus of study, he extends the project of developing multispecies social theory by puzzling out techniques for applying social theory to nonhumans. To do so well, he argues, ethnographers should “step out of our disciplinary comfort zone and attempt a far more radical interdisciplinary engagement with ethology” (257). In other words: while the science itself has much to answer for, multispecies ethnographers leave it behind at their peril.

The disciplinary tensions between ethology and ethnography occupy a significant portion of the book’s introduction. Hartigan makes the case that multispecies ethnography can create bridges between the two fields in order to make meaningful conclusions about a single nonhuman species — a goal that heretofore has been much more aligned with scientific practices than ethnographic ones. Ethology, as Hartigan notes, is deeply rooted in evolutionary theory and has historically been directed towards studying nonhuman sociality so as to shore up species-specific boundaries around “typical” behaviours. This focus on seeking “typical” or “normal” behaviour has meant that events like the rapa des bestas were not constituted as good ethological research opportunities because they were anomalous to how the horses involved typically lived “naturally” on a day-to-day basis (7). Meanwhile, while the human social ritual of the rapa would be an obvious site for ethnographers to study, Hartigan argues that a traditional ethnographic focus on teasing out the symbolic, economic, and cultural dynamics of the event also misses the opportunity to actually learn something interesting about the horses themselves.

Hartigan locates the earliest historical records of this ritual’s existence in the 1500s, though it may be even much older than that. For hundreds of years, the gathered horsehair filled mattresses and provided strong binding materials for many household uses, even into the 1960s (1–5). For humans, the event symbolizes many old and new tensions. As the event’s name suggests, both the horses and the people who gather and shave them are identified as “beasts” (bestas) and “beast keepers” (bestieros), which distinguishes them in classed terms from other horse cultures in the region, and moreover distinguishes the horses from other kinds of wildlife (2).

This class tension has been reinvigorated by postwar economic shifts. Now, rapas are primarily social and tourist events, given that horsehair is no longer a commodity and many villages where the rapas occur are depopulating due to the lack of profitable work. Hartigan briefly tracks the shifting meanings of the rapa within this growing precarity of agricultural life in the region: the events provide opportunities for young people who have left their villages for work in urban areas to temporarily return; for agricultural communities to mark and celebrate old traditions; and for struggling villages to infuse tourist spending into their economies. While acknowledging the historical and cultural ramifications of this larger context, Hartigan argues that it is not his intent to pursue further analysis of this particular set of tensions, since those are primarily human concerns. His aim is to leave such human concerns in the background and study how these horses experience the rapa. Hartigan’s central research question is “what impact does this ritual have on the social structure of these horses” (7)?

This defection from traditional ethnography is part of an extended and imaginative conversation Hartigan engages in with Clifford Geertz, whose essay “Deep Play: Notes on a Balinese Cockfight” laid the foundations of modern ethnography but simultaneously set up nonhuman beings as fundamentally unknowable (and unimportant) within the larger human dramas that provide the main subject of cultural analysis. Among the many bones Hartigan picks with Geertz across the book, seeing the animals in multispecies events, such as the horses in the rapa, as a “representational screen” rather than rich analytical subjects themselves is rebuked as a deeply rooted shortcoming that multispecies ethnographers should confront rather than reproduce (9). As a corrective, Hartigan also engages in a long-form conversation across the text with the sociologist Erving Goffman. In the book’s introduction, Hartigan uses Goffman’s critique of social researchers’ overdependence on studying verbal language to frame his adoption of Goffman’s concepts of “face” and “civil inattention” as useful for analysing equine behaviours (11). “Face”, in particular, provides a critical juncture between the ethological and the ethnographic. Hartigan’s application of this social theory concept to his observations of horses across the chapters makes a compelling case for the applicability of social theory to equine relations. He makes similarly convincing use of the concepts of “boundary work” and the “social gaze” to explain why horses are appropriate subjects for these analytical tools. Crucially, Hartigan explains how ethological knowledge, such as the equine ethogram, provided both a critical base of existing knowledge of equine behaviour to work from and a site of critique that his application of these relational concepts could help reframe. Throughout these observations, Hartigan situates the rapa as an ideal site to show the pathways through which ethology and ethnography have been talking past each other — and emphasizes how a new engagement between these methodologies can yield important information about horses and hopefully other social species as well. The implication for multispecies ethnography is that it, too, can contribute meaningfully to important conversations about nonhuman species themselves — not just the relationships between species or between nonhumans and humans.

In order to see the horses fully not just as reductively-constructed individuals in a process of evolution as ethology traditionally sees them, or as symbolic representations of human concerns as ethnography traditionally sees them, Hartigan hazards the argument that ethology and ethnography won’t just benefit from mutual proximity, but that in order to achieve more nuanced, complex understandings of nonhuman beings than we currently can, these disciplines might actually need each other.

In the three main chapters of the book, Hartigan walks this walk in the style of an extended field journal that documents his observations and analysis over the span of two weeks spent in Galicia. Chapter one, “Into the Field,” records six days that Hartigan spent learning field research techniques from two local ethologists. Each day’s work ranges across both geographical and methodological territories. Hartigan records his own process in learning ethological concepts and research techniques as he and the ethologists drive across various locations where they identify, count, and record specific horses and behaviours. Woven into these descriptive passages are extended reflections on how these techniques, and the explanations his teachers give for using them, convey the strengths and blind spots of ethological work. In one episode, Hartigan points out his guides’ frustrating refusal to “see sociality” in interactions between horses taking place outside of an ethologically-defined band structure; if the ethologist did not think an observed affiliative gesture was “functional”, then he was resistant to recording or ascribing any meaning to it at all (43). Yet he gives his teachers credit for pursuing research and teaching projects that are working to dismantle other deeply-ingrained biases in the field.

Most compelling in this chapter is Hartigan’s tracing of his own ethological skill-building when learning to observe these horses in their own ranges in the mountains. In analysing what he is being asked to do and the kinds of equine behaviours he is witnessing from his own ethnographic position, Hartigan is able to both absorb and reflect on the intermingling of these disciplines — and on what he is seeing from the horses — in concrete and experiential terms. How do ethologists think, what do they see, what do they make of it, and why? What is helpful about their approach, and what is not? When he describes spending hours sitting in the grass attempting to blend in with the gorse watching horses and practicing various techniques of sampling, Hartigan admits to intermingling those ethological techniques alongside the lenses of boundary work and civil inattention. The chapter openly discusses the gaps and uncertainties that arise between these two modes of interpreting equine interaction.

This style of analysis continues in the second chapter, “Bands”, where Hartigan leaves the ethologists to spend five days on his own observing groups of horses on the range, ethologically known as bands, and practicing the techniques he had just learned. His first day’s entry documents his time spent primarily among humans, and it fills in much of the recent historical and economic context of the rapa and contemporary concerns about the continued existence of the bestas in the face of rural depopulation and agricultural economic decline. The remaining four days are spent nearly entirely in the respectfully distant company of the bestas themselves, observing the groups of horses who are most likely to be herded down from the mountains for the rapa so as to set up a comparative study where Hartigan can document their day-to-day sociality and chart what happens among recognizable groups during the disruptions of the event to come. As the horses react to various situations that arise in the course of each day, he finds many tenets of ethology, such as the concept of “harem maintenance” by stallions, utterly unsupportable (128). Throughout the chapter, Hartigan takes particular aim at the gendered assumptions built into ethological concepts and compares them to the observed realities on the ground. For readers, this helps us see how observed behaviours in the bands distinctly contradict the assumed position of privilege stallions occupy in ethological understandings of how bands operate. Hartigan parses this discrepancy by pointing out that ethological research is primarily oriented towards documenting the behavior of single individuals; a “band”, in this framing, is interesting insofar as it is a gathering of individuals. This focus allows many aspects of sociality to go unobserved — and thus it becomes ripe for assumptions like individual stallion dominance to become inscribed.

Through several examples, Hartigan shows how an ethnographic approach to studying social relations reveals just how often “ethological terminology […] is burdened by a narrow focus on individuals” (138), and indicates where a more fluid sense of an individual’s positionality within a group might actually yield more accurate ethological data about how groups of horses negotiate space (151). This critique is not to discount his newly gained ethological skills, but rather to ponder if perhaps an ethological / ethnographic account of the bestas is greater than the sum of its parts. He writes, “I am drawn to what I can take from ethology: an attention not to inner thoughts and experiences but to the observable range of interactions that generate sociality through bonds and boundaries, affiliations and agonistic gestures that amount to a continuous performance of group identity through socially situated selves” (153). Nevertheless, the impulse in ethology to affix large ranges of observed interactions with stable terminology chafed against the data at times; for example, I was unsatisfied by Hartigan’s adherence to the ethological term “bands” to describe the groups of horses he observed. Based on just a few days of observations, it appeared to me that “band” was too strict a term for the loose and ever-shifting affiliations of horses under observation. Horses were shuffling in and out of different configurations almost constantly, and while it was clear that certain horses had strong bonds and familiarity, “bands” as a term intended to define distinct groups did not effectively capture these ins and outs.

It is now time for the three days of the rapa festival itself to begin the next day, and for Hartigan’s observations to shift towards what these horses do under the duress of being driven down the mountains, penned up, shaved, and released. Chapter three, “Ritual Shearing: Dissolution and Chaos”, recounts Hartigan’s participation in the rapa. The chapter begins as the horses are driven by people on foot down from the mountains into a large pasture, or peche, close to town. While this peche confines the bands together, there is still a lot of space for the horses to negotiate how that space is shared. During the course of each of the festival days, the horses are moved from the peche to the curro, a small arena surrounded by stands full of enthusiastic human spectators, and which becomes filled to its very brim with horses. This arena is also the site of the shaving of manes and tails, so for a few hours each afternoon it becomes a whirling chaos of ever-moving equine and human bodies jockeying for space and position. Then, the day’s shaving complete, the horses are guided back to the peche, where there are left alone for the overnight hours. Hartigan skilfully keeps his, and our, focus on the horses as the festival itself swirls in the background. There are two key stretches of this chapter that are particularly compelling. First is a thread that traces his application of Goffman’s concepts of “face” and “civil inattention” to the horses’ behaviours in the curro. Using illustrative photos, Hartigan deftly and convincingly shows this social theory in action amongst the horses themselves as they try to maintain bodily and social equilibrium in an increasingly destabilized environment. The second is his close attention to how sociality is rebuilt among the horses after it reaches a breaking point on the first day of the rapa. The first afternoon in the curro dissolves into rampant inter-equine violence as their ability to maintain “civil inattention” collapses under the amount of crowding they experience. The “microaggressions” used to maintain space when the horses were in the mountains turn into actual aggressions once that space has been compressed (212).

Yet by observing the slow and often agonizing process by which the stressed and exhausted horses begin to reconstitute their pre-existing (if always fluctuating, as Chapter 2 showed) relationships once they are back in the peche at night, Hartigan is able to see how important and resilient their capacity for sociality really is, and how myths about harems and dominance — whether those myths reside in ethological or cultural housing — utterly miss this key element of equine reality. Where ethologists would be wont to say that what can be known of horse experience, or the “really real”, can only be accessed in “natural” settings where humans are not involved, Hartigan mounts a thoughtful repudiation. For him, the “‘really real’ of the horses is both legible and fascinating” across the days of the rapa, which reveals their extreme capacity for equine behavioral plasticity rather than ethological fixity (249). By the third day, Hartigan reveals, the horses have learned to navigate the minimal space of the curro so adroitly that their ability to perform civil inattention and control their own gestures towards other horses reveals strong efforts at restraint. During these observations, Geertz appears as a visitation to Hartigan, with whom he imaginatively converses as they sit “together” at the edge of the curro. Explaining to Geertz and to us how the horses themselves achieve stillness and calm in the curro on this final day — in stunning contrast to the absolute melée of the scene two days before — Hartigan rests his case for positioning horses as ethnographic subjects and sociality as an ethological imperative.

The book’s brief conclusion summarizes Hartigan’s main ethnographic takeaways from his field observations and draws on them to revisit his methodological interventions laid out in the book’s introduction. In these closing pages, Hartigan offers a novel bridging framework that he calls “species-local” analysis to attempt to square the ethology / ethnography divide. “When ethologists observe animals,” he notes, “they think and write in terms of ‘species-typical’ behaviors […] that result from evolutionary processes and a species’ interactions with particular environments, and they are largely construed as fixed behavioral dynamics” (253). There is important utility in this approach, but in Hartigan’s formulation, in hewing to the “prevailing assumptions” about what a species is and what it does from this fixed position, we blind ourselves to what else is possible — indeed, to what else is actually happening. The term “species-local” is designed to draw from ethological understandings of species specificity but to give it some, well, give: “the value of a species-local account is that it can call attention to an elasticity, variability, and dynamism in social behavior that would not be evident in naturalistic settings” (253). The “local” part of the term refers to the ability to make valuable observations of a social species, in this case horses, in any context — one can attend to the species-specificity of their experiences without shutting down the opportunity to learn about them as horses when they are interacting with humans or in situations that are mediated by forces, including human forces, that lie beyond their desire or control. Hartigan makes the case that this concept can be applied beyond the equine examples he has charted in this project to many other species that have been designated as social species by ethologists. If we are to follow his example successfully, this opens up an exciting range of possibilities for multispecies ethnographers to contribute to an enlarged and hopefully more accurate understanding of cetaceans, primates, birds, and beyond. A thrilling prospect! But though the counsel here for an audience of ethnographers is to not lose sight of species-specific knowledge derived from the sciences when conducting multispecies ethnographic work, it is clearly aligned with ethnography as the discipline with the most benefits to contribute to this larger project. All in all, this book is perhaps more an ethnography of equine ethology as it is an ethologically-informed ethnography of the bestas and the rapa.

The amount of evidence Hartigan is able to amass in such a short period of time to support his novel insights into equine behaviour is a testament to the solidity of his hypothesis and the usefulness of extending an ethnographer’s skills to nonhuman subjects. Yet while Hartigan’s observations are extremely thorough and detailed, his sample size is small. He notes that there are over 11,000 horses roaming the mountains of Galicia; his own observations concern a tiny sliver of them, just a few hundred at most. Likewise, the entire study unfolds over just eleven days — which Hartigan himself confesses is barely enough time to even begin reliably recognizing individual horses, let alone getting to know their patterns. Someone who has lived with horses and observed their daily habits over long periods of time — months, years — can pick up innumerable nuances in their actions. Hartigan’s observations as a non-horse-person yield admirable progress in recognizing their subtle communications, from ear movements to nose wrinkles; however, it would take a much longer observation period to fully document who was who and chart the possible range of socialities of any of the bestas in the book.

The implications of Hartigan’s analysis are manifold. Hartigan gestures to the oncoming rush of climate emergency as the most urgent impetus for multispecies ethnographers to document the relations we can, now. Indeed, one shadowy implication of the text is that, given extremes of planetary temperature and their effects, there will be literally less space on the planet to house us all, making us a kind of analogue of the horses in the curro being pressed ever closer against strangers as our social practices fray. If this is the distressing analogy we are to make, then the text has a hopeful conclusion — first, that at least with this study of horses, it turns out that our own capacity for adapting our sociality to stressful circumstances might be stronger than we think. And secondly, we, as humans who can somewhat govern our responses to whatever version of this analogy the future brings, can learn even more about sociality under duress by learning from other species in an ethnographic context. This looming imperative, while quite valid if not directly invoked, nevertheless undercuts the argument that we should be looking to ethnography as a way to learn more about animals as animals rather than, well, representations for us humans to use as a compass to navigate ourselves through our crises, however urgent and biodiverse they may be. Perhaps it is a persistent breeze coming in from his ghostly seatmate Geertz in the curro. But really, Hartigan does not need this larger context to prove the value of his approach. As a horse person, I found the application of social theory to his observations and analysis of equine behaviours convincing; it reframed and affirmed many observations that were true to experience, and taught me new information that I am glad to know now, as it will affect how I make choices about interactions with horses henceforth. My hope is that this work gets into the hands of practitioners as well as scholars — into the hands of people for whom social theory has heretofore been an uninteresting and uninviting pursuit. Horses and people who care about them can connect to this work from a number of angles and find something about their own knowledge and experience reflected in Hartigan’s careful, earnest observations and approachable analysis, particularly in the three main chapters which are written in plain and engaging language. This book has the potential to do a lot of good for horses right now.

And ultimately, that was the question I started with many years ago: what’s in it for the horses? If the role of the multispecies ethnographer is to expand our understanding of the species in question not just relationally, but also as such, then there needs to be an ethic not just of epistemological clarity but of potential species benefit as well. This has been a stumbling block for ethologists, whose commitments to “objective” observations in a “natural” environment tend to sidestep any commentary on how to apply knowledge in a way that improves outcomes for horses who live in so-called “unnatural” environments. Horse people, though, can really stand to benefit from having clearer “species-typical” and “species-local” understandings. In the careful work of the book’s third chapter, observing the horses perform the gestures of sociality through Hartigan’s eyes taught me a good deal about what the horses needed and prioritized. In witnessing how the ritual of the rapa took those necessities away — which is what made me so uncomfortable when first seeing photos of a rapa in the workshop many years ago — his insights from social theory provided direction for understanding equine beings and how to craft positive, clear strategies for supporting their relational needs. Hartigan’s findings about equine sociality under duress are widely applicable towards strategizing how we can improve equine lives when we humans make decisions about their care, the spaces they inhabit, and what we ask them to do with us.

But I do still wonder, what about the bestas themselves? It seems to me that for this unique and ancient population of horses, the utility of the findings are less clear. Hartigan claims that “ethnographic method has allowed me to avoid reproducing yet another account of representation and instead learn something about the social lives of these horses” (247). Yes, emphatically yes — but part of the “really real” for the bestas is the continuation of the rapa, which is itself a representational activity that exists to make meaning for the humans who organize them. What do we do with that aspect of the “really real”? The very existence of the bestas might depend on the continuation of this ritual. This circumstance arguably makes their own experience of the rapa secondary to its representational and symbolic function among humans. The horses and people of Galicia, bound together by a contracting and shifting agricultural economy, share an existential concern. For the horses to continue existing, they have to mean something to people, whether to the townspeople themselves or the tourists who are keeping this precarious economy afloat. These are questions that revolve around representational conclusions as much as social ones. In their case at least, the bestas need us to understand not just who they are, but also what they mean — which perhaps is a “species-local” question after all.

Notes

The third instalment, Social Theory for Nonhumans, currently exists as a web site hosted by the University of Minnesota Press.