Interspecies Mapping and Timing

A View from Mithun Country

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.18820

Keywords: Interspecies history, Bos frontalis, mithun, Himalayas, animal sacrifice, area studies

Email: h.w.vanschendel@uva.nl

Humanimalia 15.1 (Fall 2024)

Abstract

This article argues for an interspecies methodology to challenge the human-derived spatial and temporal constructs that underpin most historical narratives. It also seeks to qualify the entrenched dichotomy between wildness and domestication.

To this end, I focus on the interaction between humans and “mithuns” (Bos frontalis), bulky bovines endemic in the mountain forests of the eastern Himalayas. In this large region—covering parts of India, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and China—numerous societies attuned their cultural sensibilities and cosmological assumptions to the same animal. This remarkable feat of cultural convergence attests to the unwitting power that a semi-wild bovine exerted over generations of humans—a fact that environmental historians can incorporate into their analyses of interspecies agency.

The significance of mithuns to humans had nothing to do with their livestock potential. They were sacred animals that humans needed to communicate with supernatural forces. The form that this communication took was ceremonial sacrifice. During the twentieth century, however, mithun–human relationships morphed into a new sacrality of place, ethnic identity, regional belonging, and political resistance. This transformation suggests the need for an “interspecies periodization” that takes human-nonhuman temporalities seriously.

As most of these societies historically did not use script, written evidence is not plentiful. Therefore, Indigenous forms of knowledge production about the environmental past—embedded in songs, stories, dances, rituals, material remains, dress, and sculptural art—are of paramount importance. These shaped human behaviour towards mithuns in the past, and they continue to do so today.

Look! As evening falls, a hefty animal emerges from the dense mountain forest. It saunters towards a nearby village where a man offers it some salt. Then it returns to the forest. You have just witnessed a mithun–human encounter.

As historians move away from unreasonably anthropocentric history, they are exploring interspecies pasts more forcefully than ever before.1 An important focus is on how relationships between humans and other animals have shifted over time. This article is intended as a small contribution to this discussion. It considers an animal habitat — “Mithun Country” — that straddles the boundaries of three world regions that scholars have long treated as distinct civilizational entities. The historiographies of these regions — “South Asia”, “Southeast Asia”, and “East Asia” — are separated by the academic conventions of “area studies”, which are hard to overcome.

Taking Mithun Country as our starting point, we can develop a historiography that takes human–nonhuman relationships seriously and questions the human-derived spatial and temporal constructs that underpin most conventional historical narratives. In addition, we can re-examine an entrenched dichotomy in the study of human–nonhuman relationships: the contrast between wildness and domestication.

I focus on the interaction between humans and the mithun, a bulky but little-known bovine endemic in the eastern Himalayas. The aim is to show how mithuns have long decisively shaped numerous human cultures, how intense mithun–human relationships metamorphosed over the course of the twentieth century, and how interspecies spaces and times cut across purely human ones.

Mithun Country

What is a mithun? It is a large bovine that is usually described as semi-wild (or semi-domesticated). First portrayed by Europeans in 1804, it is known to scientists as Bos frontalis (Figure 1).2 Its origins have long been disputed, with many authors believing that the mithun was a domesticated form of the gaur (another wild bovine, Bos gaurus).3 However, new genetic research has confirmed that mithun and gaur are completely distinct species.4 The most recent study even rejects an earlier assumption that the two species “might have originated from the same wild bovine, which is now extinct.”5 The mithun is not a domesticate; it is a wild species that has sought limited intimacy with humans, on its own terms.

Fig. 1 Earliest depiction of a mithun (Bos frontalis), 1804.

Source: Lambert (“Description of Bos Frontalis”,

57; see also his “Further Account”). This animal

was captured in the foothills east of Chittagong.

The first description in English dates from 1790.

Early references speak of “gobbah”, “village gayal”,

“jungly-gau”, etc. Cuvier, Supplément, 92–99;

Pearson, “Memorandum on the Gaur”. See also

Macrae, “Account of the Kookies”, 186, 191–92;

Wilcox, “Memoir of a Survey”, 371–72.

The mithun is quite distinct from the better-known gaur in its appearance, distribution, genetic make-up, and behaviour — and its habitat is far more restricted.6 Mithuns are mountain dwellers (at altitudes from 300 to 4,000 m) in the eastern Himalayas (Figure 2).7 They prefer deep forests in steep foothills and higher slopes, shielded from the sun, and near rivers and salt licks.8 Their primary food consists of tree leaves, shrubs, bamboo shoots, and herbs — not grass.9 They are found only in Mithun Country, which snakes through Bhutan, Northeast India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and China (Figure 3), thereby connecting the academically distinct areas of “South Asia”, “Southeast Asia”, and “East Asia”.10

Mithun Country is a spatial entity that we can use as a building block in environmental history because it is not only ecologically but also culturally significant.11 The humans inhabiting the mithun habitat are culturally and linguistically extremely diverse, but these cultures share a remarkable regard for mithuns.12 Linguistic evidence points to “the deep-rooted importance of mithun culture in the region” and to the mithun being seen as a “prototypical” animal. In some of the region’s languages, the names of all other animal species are even derived from its name.13

Fig. 2 A mithun in Arunachal Pradesh (India).

Photo by Willem van Schendel.

Fig. 3 Mithun Country

Pachuau and Van Schendel, Entangled Lives,

49–50, 117–19, 173–83.

Mithun Cultures

The mithun is a rare occurrence in conventional archival records because most societies in this region did not use writing — nor were they part of larger states — in some cases up to the eve of the Second World War.14 As mithuns themselves left few traces, studying human–mithun relationships is methodologically challenging. Written sources began to appear in the nineteenth century, but they tended to represent outsiders’ (mostly travellers’ and British imperial officials’) views of the human–mithun relationship.

Emic perspectives can be gleaned from other sources, however. Megaliths, woodcarvings, and textiles are sources of evidence that can be understood as expressing human–mithun mutuality. Many local art practices featured the animal, especially its head, which was considered its sacred core (see Figures 4 to 6 for examples). In this dispersed archive, mithuns are anything but marginal or incidental.

Other rich sources of information are stories, songs, dances, rituals, and place names in the many languages of Mithun Country.15 In these sources, mithuns often play a crucial ontological role, connecting the deep past with living memories. This significance was unfamiliar to the outside world until anthropologists began to publish written versions of stories, revealing them to be rich and varied.

Fig. 4 Megalith in Champhai (Mizoram, India) showing humans and mithun skulls.

Many memorial stones across Mithun Country depict full-bodied mithuns or, more frequently, mithun skulls. These stones are very hard to date but they are generally thought to be several centuries old.

Pachuau and Van Schendel, Entangled Lives, 176–77.

Photo by Willem van Schendel.

Fig. 5 Wooden representation of a mithun skull in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (Bangladesh), 1961.

Van Schendel et al, Chittagong Hill Tracts, 156.

Photo by David Sopher, 1961.

Fig. 6 Mithun heads on a village gate in Tuophema Tourist Village, Nagaland (India).

For explanations of this Angami Naga design, see

Mills, Ao Nagas, 78; Hutton, Diaries, 23; Kauffmann,

“Bedeutung”.

Photo by Willem van Schendel.

For as long back as we know, mithuns have been key to the lifeworlds of many humans across Mithun Country. They became the prime sacred animals in the region’s various and distinct religious traditions, which are often lumped together as “animism”.16 The ontological value of these bovines derived from the fact that they figured prominently in origin stories, played a pivotal role in mediating between humans and supernatural forces, and could act as guides to the afterlife.17

The cosmological significance of mithuns was underpinned by stories of their crucial role in the creation and maintenance of the world. Several stories spoke of the world originally being covered with water, until “a great mithun dug a pit into which the waters poured and allowed the dry earth to appear”.18 Another story held that “the only creatures in the early world were two spirits, one of whom had the form of a mithun and the other the form of an elephant. They fought and killed each other and from their flesh and bones the world was formed.”19 A third explained that the first mithun tossed the sky up with its horns, creating a living space underneath for humans to inhabit.20 And there was another belief that a great mithun supports the earth on its body. Its regular movements produce the seasons. When it twitches its ears, it causes a small earthquake, and when it suddenly moves its whole body, a large earthquake occurs.21 The closeness of humans to mithuns was also expressed in numerous stories that portrayed mithuns as kin.22

A Salt Partnership

Mithuns are free-roaming forest animals that do not depend on humans for food or procreation. Humans did not hunt them. Mithuns were not fed, kept in pens, worked, or milked. Placid and shy, they may over centuries have tolerated human company for a single reason: a mutual love of salt. In stories about human settlement in Mithun Country, a recurring theme is that mithuns pointed humans to saltwater springs in the forest, after which people moved and settled in the area.23

Humans did not domesticate mithuns. These bovines remained forest animals with a friendly attitude to humans. They tended to wander and disappear into the mountains, so humans regularly searched the forest to entice them with salt.24 Mithuns could also come near a human settlement once every few weeks to get access to some salt (Figures 7 and 8).25 Either way, humans used salt to create and maintain a bond with mithuns. They fed baby mithuns salt to encourage loyalty to the person providing it. Humans could identify free-roaming individuals by bodily signs: the colouring of their coats, their body size, the shape of their horns, and the small slits that humans had made in mithuns’ ear lobes. Based on these signs, humans claimed ownership.26 But mithuns defied this anthropocentric label. They remained semi-wild, challenging conventional categories of wildness and domestication.27

Fig. 7 Mithuns in a forest clearing approaching a man who has put salt on rocks.

Aiyadurai, “‘Tigers are our Brothers’”, 78.

Photo by

Ambika Aiyadurai.

Fig. 8 A mithun in Bangladesh receiving a handful of salt, “the only reason it comes into the village.”

Brauns and Löffler, Mru, 131.

Photo by Lorenz G. Löffler.

Mithuns as Intermediaries

Remarkably, the significance of mithuns to humans had nothing to do with their livestock potential. First and foremost, they were seen as sacred animals — the only living beings capable of moving between the parallel worlds of the forest and the village.28 They were thought to have a special relationship with the spirits of both forest and village, and humans needed them as intermediaries to communicate with these supernatural forces.29 The form that this communication took was ceremonial sacrifice.30

Mithuns were not the only sacrificial animals in Mithun Country, but they were by far the most sacred, topping a list of lesser sacrificial animals.31 Mithuns were enveloped in cosmological significance: spirits were known to dwell in and around their horns and around the rope with which they were led and tethered.32 As the highest-ranking nonhumans, mithuns even had chickens sacrificed to their souls:

Oh female mithun! May the villagers speak well of you. Don’t get hurt, don’t sprain your legs, be well, may your prosperity be manifold and assured […] and wherever you go, may your journey be good. I call your soul with a chicken.33

Mithun sacrifices were at the heart of an elaborate system of ceremonial feasting.34 The preparations and interactions surrounding this ritual varied between different human groups but all of them acknowledged the cosmological significance of the event. People would wear distinct dresses for the ceremony, and mithun remains could be wrapped in a specially embroidered blanket.35 Afterwards, mithun meat was ceremoniously shared and consumed and each mithun skull was carefully preserved and displayed on a sacred skull rack (Figures 9 and 10).36 The cosmological and social significance of these “feasts of merit” was underlined by lasting commemorative symbols: wooden sacrificial posts, carved ceremonial stones showing mithun horns, and decorative wooden “horns” on the roof of a feast-giver’s house (Figures 4 and 5).37

Through these sacrifices, mithuns became powerful symbols of status and (among some groups) fertility.38 Ceremonial feasting was concurrently individual, in that it offered prestige and power to the organizer, and communal, in that it distributed spiritual benevolence and wealth among a community.39 Mithun sacrifices were “religious, social and economic action” that accompanied trade deals, peace treaties, friendship pacts, marriages or deaths, and times of illness or misfortune.40 As many as forty mithuns could be lured from the forest to be sacrificed in a single ceremony but in most cases a single mithun sufficed.41 Human well-being across Mithun Country critically depended on these sacrifices, which showed that humans needed mithuns far more than mithuns needed humans.

Fig. 9 A mithun sacrifice, early twentieth century.

Mizo Zirlai Pawl (MZP) collection.

Photographer unidentified.

Fig. 10 Skulls of sacrificed mithun and other animals proudly exhibited near the India–Myanmar border, 2012. The souls of these animals were thought to guide departed human souls to the afterlife.

Lehman, Structure of Chin Society, 179–82.

Photo by Willem van Schendel.

Mithuns as Badges of Identity

In the twentieth century, the societies of Mithun Country changed, Christianized, and gradually became incorporated into contemporary nation states. The symbolic meaning of the mithun shifted.42 In many cases, the ancient religious significance of the animal faded away. But mithun-human intimacy persisted. This closeness was expressed in many ways — humans felt they could decipher non-verbal mithun signs such as twitching ears or swishing tails, and occasionally they channelled the mithun’s voice. In a nostalgic lament (written by recruits on their way to wartime France in 1917), the mithun spoke its mind: it “grunt[ed] not wanting to bid farewell”.43

The spread of Christianity among the region’s mithun-oriented mountain societies occurred at different times, because their encapsulation into British India occurred at different times. For example, the British attacked and annexed the Chin and Lushai hills (today: Mizoram in India and the Chin State in Myanmar) in the 1890s, after which missionaries began proselytizing. A generation later, many inhabitants had become Christians.44 In the Naga hills this process had started much earlier, and in the region south of the Lushai hills Christian conversion did not commence until the 1940s. The church did not allow animal sacrifices, and yet many Christians continued to “show their reverence for this traditional sacrificial animal”.45 They slaughtered mithuns only for very special occasions — community celebrations such as Christmas and weddings — during which the meat was shared and consumed largely in the traditional manner (Figures 11 and 12).46

Fig. 11 Two mithuns to be slaughtered for Christmas in a Mizoram (India) village, 1944.

Vanlalmawii collection. Photographer unidentified.

See also Pachuau and Van Schendel, Camera, 80.

Fig. 12 Sharing Mithun meat among Christian graves, circa 1956.

Aizawl Theological College collection.

Photographer unidentified, possibly Gwen Rees

Roberts (Pi Teii).

With the passing of colonial rule, Mithun Country was administratively dismembered. As new nation-states were forged, mithuns became confirmed crossers of the new state borders. They also emerged as an eco-cultural resource that allowed the people of Mithun Country to emphasize their regional identity. Ideas of regional belonging (sometimes across new state borders), self-determination, and Indigeneity crystallized around the figure of the mithun. With the development of new ethnic categories all over Mithun Country, mithuns came to represent these categories and their boundaries.47

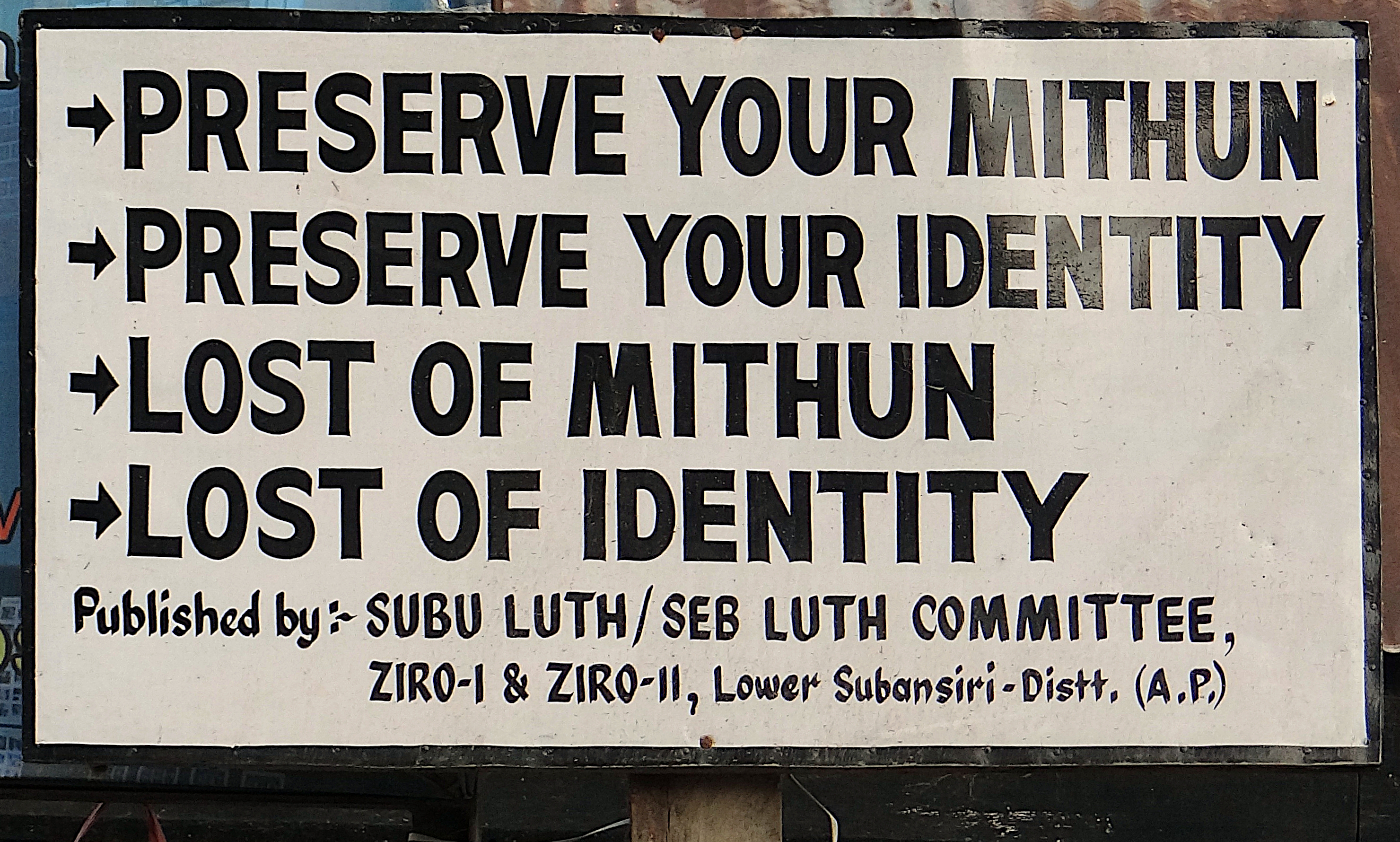

During the closing decades of the twentieth century, the mithun motif was expressed with increasing intensity and defiance. It marked cultural opposition to nation-building projects, especially in the states of Northeast India. This could take the form of a nostalgic re-enactment, a festive dress, body art,48 a warning, or a festival (Figures 13 to 15). The mithun has also appeared in modern literature.49

Fig. 13 Re-enacting a mithun sacrifice in Mizoram (India) in 1995.

Mizo Zirlai Pawl (MZP) collection. Photographer

unidentified. For a similar ritual in China,

performed for tourists in 2006, see “Jiànzhèng

dú lóngzú jìsì yíshì” [Witness the Dulong

people’s sacrificial ceremony], Sina News Center

(10 May 2006), https://news.sina.com.cn/c/cul/p/2006-05-10/12209821244.shtml.

By 2016, the sacrificial animal had been replaced

by an enormous mithun effigy. See “Yúnnán dú

lóngzú qúnzhòng huāndù ‘kāi chāng wǎ’ jié”

[People of the Dulong ethnic group in Yunnan

celebrate the “Kaichangwa” Festival]. China in

Pictures (4 February 2016). http://photo.china.com.cn/news/2016-02/04/content_37733811_2.htm.

Fig. 14 A mithun head adorns a man’s jacket at a formal village meeting in Nagaland (India).

Photo by Willem van Schendel.

Fig. 15 A billboard in Arunachal Pradesh (India).

Photo by Willem van Schendel.

In addition to these eco-cultural appropriations, the mithun also became a powerful eco-political resource. It signalled the political distinctiveness of the region. Two Indian states — Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland (Figure 16)50 — adopted the mithun as their “state animal”, which is interesting because state animals are always wild species.51 Mithuns thus became overtly political animals. Various emerging counter-elites in Mithun Country embraced the mithun to express regional anger, (sub)national aspirations, and armed struggles against state forces and coercive extraction (Figure 17). The title of a book about one of these regional aspirations articulates these feelings well: The Raging Mithun.52

The historical intimacy of mithuns and humans across Mithun Country continues today under vastly different circumstances. The sacrality of the animal as an indispensable go-between with supernatural beings has largely morphed into a new sacrality of place, ethnic identity, regional belonging, and resistance to state coercion. Mithun sacrifices dwindled with the spread of Christianity, but mithun imagery flourished.53 And this imagery emphatically highlighted the mithuns’ wild, untamed, and self-reliant characteristics.54

Fig. 16 The government seal of Nagaland (India)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 17 Emblem of the Kuki National Organisation, which fights for the establishment of Zale’n-gam, an independent state to unite the Kuki people now living under Myanmar, Indian, and Bangladeshi rule.

Source: http://kukination.blogspot.com/2011/12/kno-kuki-national-orginasation.html

Mithuns as Livestock

At the same time as locals re-imagined the mithun as a wild animal serving as a new emblem of regional distinctiveness, policy makers and scientists imagined the animal in a diametrically opposed manner: as a domesticated animal with commercial potential.55 To them, it was a potential economic resource. Claiming national intellectual property and state control over mithun bodies, they made them a target of “scientific husbandry” and trade. In Myanmar, government plans involved army-controlled wildlife smuggling: the military rounded up mithuns and exported them (or their excellent meat) from Chin State to India.56 In India a “National Research Centre on Mithun” was set up in 1988, with a view to exploiting and “developing” mithuns for their meat, milk, and leather.57 Similar but smaller initiatives were undertaken in Bhutan (1970s), Bangladesh (1990), Myanmar (1990s), and China (2000).58 Mithuns proved difficult to manage, however, partly because they are prone to fall victim to disease and die when taken to livestock farms, especially in the lowlands, as was the case in Bangladesh.59 Scientists considered free-roaming to be “suboptimal”, however, so they promoted “semi-intensive mithun rearing units”, in which mithuns would roam freely during the daytime but were brought back to pens at night.60 Genomic sequencing, semen selection, and biomedical research sought to frame the mithun as domestic livestock to be “improved” and manipulated.61 This utilitarian approach marked a complete disregard for the mithun as a wild species, to be sustainably preserved and protected together with its ecosystem of broad-leaf (sub)tropical forests.62

Meanwhile, the mithun population was declining because of habitat destruction, crossbreeding, and climate change.63 Mithuns are sensitive to heat and sunshine, and they respond to rising temperatures by moving up the mountains into deeper, cooler forests close to rivers and salt licks. There are indications that this affects the traditional intimacy between mithuns and humans because mithuns now live farther from human-inhabited spaces and no longer respond to salt-offering humans who call them.64 Thus, climate change may have the effect of making mithuns more “wild.”

Interspecies Space

What does this brief example tell us about imagining space and time in environmentally sensitive ways? By taking an animal habitat to work towards how humans have made their living in it, we may open our minds to hitherto neglected interspecies geographies and suggest new entry points into the past. The space of Mithun Country is relevant because it emerged from animals. Humans all over this area — and only this area — developed profoundly meaningful connections and affinities with mithuns.65 They integrated these nonhuman animals fully into their cultures.66 And mithuns similarly developed ways to open their lifeworld to intermittent contacts with humans.

Arguably, other animals were also significant for humans in Mithun Country. The tiger and the hornbill (a large forest bird) played important roles in regional cultures as well, but there were three important differences. First, only the mithun became an indispensable intermediary between humans and supernatural beings by means of communal sacrifices. Second, the tiger and the hornbill are not restricted to Mithun Country; their habitats spread far beyond it, affecting other cultures differently. And third, only the mithun straddles the wildness–domestication divide, producing an interspecies partnership that differs fundamentally from human–tiger or human–hornbill relationships. Uniquely, the mithun’s natural habitat became a well-defined human cultural space.

Practitioners of the environmental humanities ponder which spaces are relevant to which research questions. Mithun Country obviously does not follow human territorial boundaries (state borders, area studies, ethnic divides), but neither does it fit broad ecological spaces, such as watersheds, climate zones, ecoregions, or the “global biodiversity hotspots” that guide much current research. Mithun Country crosses the boundaries of nine internationally recognized terrestrial ecoregions.67 It also straddles three global biodiversity hotspots: “Indo-Burma”, “Himalaya”, and “Mountains of Southwest China”.68

These boundary crossings show that broadly drawn ecozones must be disaggregated to study specific interspecies histories effectively. Mithun Country is an example of an environmental zone defined by mithun–human reciprocity. The mithun is endemic in this space, and over time this space has become the home of a group of mithun-oriented human cultures.69 A distinctive interspecies geography took shape, a vernacular corridor that defiantly wends its way through the eastern Himalayan uplands.70

Generations of scholars have repeated the unproven view that the mithun is a domesticated form of the wild gaur.71 It might be closer to the truth to say that, historically, wild mithuns have approached human newcomers who entered their domain thousands of years ago, and that these mithuns thereby domesticated humans to become salt-dispensing partners, while keeping their own freedom to roam at will.72 In turn, humans acknowledged the might of mithuns by imagining them to be creators of the world and formidable mediators with supernatural powers on behalf of humans. Looked at in this way, the mithuns unintentionally led the way in creating a unique relationship between nonhuman and human animals that challenges the routine distinction between “wildness” and “domestication”, and between “nature” and “culture”. Evidence from Mithun Country shows that local thinkers did not make that distinction in quite the same way.73 Rather, they saw an all-inclusive universe in which spirits, nonhuman animals and humans formed dynamic partnerships of respectful reciprocity. In this encompassing environmental space, mithuns acted as guides to humans, and as crucial go-betweens between humans and spirits.

Interspecies Time

The example of Mithun Country also alerts us to ways in which the narratives of the environmental humanities might deal with temporality. In Mithun Country, the conventional periodization that professional historians use to organize their narratives is of limited value. Anthropocentric, state-oriented periods (for example, “precolonial”, “colonial”, “postcolonial”, or “dynasty”) are inadequate. At best, they fit only parts of the mithun habitat, and they fit these at different moments in time.74 Therefore, they fail to cover the historical development of human-mithun relations across the mithun habitat. And, crucially, they do not even correspond to how humans in Mithun Country have conceptualized time.75

Human–mithun relations have their own timescales and these can be helpful in developing interspecies periodization. For example, after a long period of religious stability, in which mithun sacrifices were fundamental rituals that structured the annual cycle as well as human lifecycles, the cosmological landscape changed.76 From the late nineteenth century, people in Mithun Country began to embrace new religions, notably forms of Christianity and Buddhism that frowned upon mithun sacrifice. This gradually altered the relationship between mithuns and humans, as mithuns lost much of their spiritual significance. But mithun meat retained its exceptional and revered aura; it was only shared and consumed during momentous community celebrations.

A further change occurred in the second half of the twentieth century, when humans native to Mithun Country began to use their historical connections to the animal to assert their sense of place, their ethnic and political identities, and their struggles against imposed state policies. As mithuns saw their forest habitat shrink, humans reinvented the mithun as an environmental badge of indigeneity, authenticity, anger, and defiance — a badge that underlined wildness and interspecies union.

A third shift took place in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, when scientists in the five states whose territories cover Mithun Country discovered the commercial potential of mithuns. They claimed mithuns as a national resource and attempted, with mixed success, to turn them into regular livestock whose meat and leather could be marketed.

We may use such human-nonhuman turning points to structure narratives of interspecies temporality. Historians are increasingly aware of the importance of more-than-human periodization to highlight our embeddedness in our ever-changing environment. In some historiographies, “catastrophic” interspecies periodization already trumps anthropocentric periodization — for example, in the study of pandemics, the Columbian exchange, mass extinctions, and global warming. But less spectacular and smaller-scale shifts in human-nonhuman relations can also contribute to much-needed guidelines for interspecies periodization. For example, Mithun Country — just one example of a specific regional space/time combination — suggests the salience of distinguishing between “eco-system-level” time (the temporality of the mithun habitat) and “single-interspecies-level” time (such as human–mithun temporality).77

Conclusion

This brief exploration of Mithun Country suggests five issues to contemplate. First, by focusing on nonhuman actors, we can contribute to overcoming the parochialism of overly anthropocentric history. Whether we look at microbes, fungi, plants, nonhuman animals, or natural elements (rivers, swamps, forests, deserts, seas, storms, earthquakes, or mountain ranges), they all help us decentre humans and take nonhuman space and time seriously. The mithun case exemplifies how nonhumans co-produce human spaces and times, often without us realizing it. Over a long period of time, distinct societies in a large geographical region attuned their cultural sensibilities and cosmological assumptions to the same animal. This remarkable feat of cultural convergence attests to the unwitting power that a semi-wild bovine exerted over generations of humans. This is a valuable finding that environmental historians can incorporate into their analyses of interspecies agency. Animals that were once seen as silent bystanders, and as props, specimens, living machinery, and commodities in human histories, are better understood as historical partners.78 This insight challenges the conceptual border between humans and nonhumans that inspires anthropocentric history — but it resonates strongly with customary worldviews in Mithun Country.

Second, environmental histories hardly ever coincide with contemporary or historical state and world-area entities. They disregard human-designed boundaries. Mithun Country straddles the national territories of India, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and China. In addition, it connects the academic templates of “South Asia”, “Southeast Asia”, and “East Asia.” It exemplifies how an environmental history approach can help us highlight complex connections between world areas. The concept of ecological “transregions” (which may overlap and change over time) has been suggested as a useful heuristic tool for crossing the notional borders of world areas.79 The borders of such transregions may be understood as co-produced; for example, mithun foraging patterns may have determined human border making.80

Third, spaces are always time-bound, so “mapping” and “timing” go hand in hand. The standard periodization of, for example, South Asian studies makes little sense in Mithun Country where diverse cultural traditions have constructed time differently, providing an opportunity to delve into the multiplicity of timing in South Asia and refine interspecies periodization.81 This is particularly relevant in the current era of rapid environmental change. As the landscapes of Mithun Country are degraded by human interference, and nonhuman habitats are shrinking, our mapping and timing must adapt accordingly.

Fourth, this tour of Mithun Country alerts us to a well-known, deep-seated problem: a fundamental distinction between the domains of “nature” and “culture” in the production of academic knowledge. Environmental history has long rejected this distinction — the environment is always a nature-culture amalgam. Put differently, the human touch is planetary, and it is a fallacy to think of humanity as existentially alienated from nature. The fantasy of an untouched, pristine, unspoiled nature produces problematic terms like “wildness” and “conservation”. The deep mountain forests that the mithuns prefer as their habitat are not pure or primeval in any sense. Like all other “natural” phenomena, they have long histories of human interference. As mithuns demonstrate by their behaviour, creatures can be “wild” and “domestic” at the same time. Domestication is best seen as a spectrum on which mithuns have never moved far, even though their intimacy with humans has deep roots.

And fifth, this case study nudges us towards studying unconventional sources of historical information (notably multilingual oral archives and material remains such as landscapes, forest habitats, megaliths, skull racks, bones, woodcarvings, and ceremonial posts) and reconsidering what constitutes relevant and reliable evidence about the past. To this end, academic historians should take locally-based, non-academic narrators of the environmental past more seriously than most of us have done. Indigenous forms of knowledge production, conveyed in local languages, are key to deciphering the Indigenous cosmologies of Mithun Country. These interpret the environment as an all-inclusive universe in which spirits, nonhuman animals and humans form dynamic partnerships of respectful reciprocity. This worldview — articulated in songs, stories, dances, rituals, material remains, dress, and sculptural art — shaped past attitudes and behaviour. And this worldview is still perceptible in modified form today.

So we, academic historians, need to distance ourselves more from that romantic figure of the lone heroic scholar ploughing endlessly through dusty records. Record-ploughing certainly remains extremely important (although increasingly on-screen). But as environmental historians have been demonstrating for years, there are essential sources beyond the archetypal archive. These have been called proxy records:

many of the questions asked by environmental historians cry out for reliable proxy records […] that may reflect, for example, deforestation, erosion, salinization, or changes in species compositions […]. While these disparate sources of data do not always combine as easily as we might like, the various material “proxy” records are an essential part of researching environmental history, even in very recent periods.82

This is a crucial point for Mithun Country because here written sources are uncommon and proxy records are the main carriers of environmental historical information. The field of environmental history is only beginning to be developed in this region, so we can put its nascent historiography on a thoroughly interdisciplinary footing, overcoming academic silos. Theoretical insights and research methods from disciplines beyond the humanities and social sciences can assist in unlocking alternative interspecies ways of “mapping” and “timing” the region. In other words, we can take a cue from the mithuns’ wandering habits, by crossing disciplinary, national, and area-studies borders ourselves.

Notes

For example, Kean and Howell, The Routledge Companion; Bonnell and Kheraj, Traces of the Animal Past; Roscher et al., Handbook of Historical Animal Studies.

Contemporary scholarly literature tends to refer to the animal as mithun. The word probably derives from an Austroasiatic language that preceded the arrival of Indo-European and Trans-Himalayan speakers in the area where this animal lives. In surviving Austroasiatic languages (Khasi, Pnar) it is known as mynthna (Simoons and Simoons, A Ceremonial Ox, 226–27; Singh, Khasi-English Dictionary, 136; Passah, Pnar-English Dictionary, 57).

In many Trans-Himalayan (Tibeto-Burman) languages of the region, the animal is known by variations of sha, sia, sial, etc. (Blench, “Contribution of Linguistics”; Aisher, “Through ‘Spirits’”, 423; Sharma, Learners’ Manipuri–English Dictionary, 190; Faruque et al., “Present Status of Gayal”, 77; Malsawmliana, “Socio-Economic Importance”, 41–42; Post, “On Reconstructing”, 330). More easterly languages know the animal as kungbam (LaPolla and Sangdong, Rawang-English-Burmese, 511) and ngepu (or ngvpuq; Perlin, Grammar of Trung, 29, 363). In Chinese it is dúlóngniú (独⻰牛), often translated as Drung ox.

In Indo-European languages the term is gayal (except for Assamese, which uses mithun, mithan, or methon; alternative spellings are mythan or maithan; Rainey, “Notes on the Chinboks”).

Another related bovine, the banteng (Bos javanicus), used to be present in the mithun’s habitat (Barbe, “Some Account”, 386) but is now thought to be regionally extinct.

There is mounting evidence that the mithun is a separate species, but it is capable of interbreeding with both gaur and domestic cattle (Wang et al., “Draft Genome of the Gayal”; Devi et al, “Revisit of the Taxonomic Status”; Tenzin et al., “Assessment of Genetic Diversity”; Bareigts, Les Lautu, 88; Li et al., “Molecular Phylogeny”; Evans, Big-Game Shooting, 64–66; Kauffmann, “Landwirtschaft”, 72; Simoons and Simoons, A Ceremonial Ox, 14–30).

Mukherjee et al., “Genetic Characterization”, 16; Devi et al., “Revisit of the Taxonomic Status”; see also Baig et al., “Mitochondrial DNA”. From the eighteenth century to the present, two hypotheses about the origin of the mithun have been put forward: that the mithun might be a domesticated form of the gaur, or that it might be a hybrid of gaur and domestic cattle. These suggestions do not sufficiently explain:

Domestication implies the physical alteration of animals by selective breeding for specific characteristics, creating organisms that differ from their “wild” forebears and usually cannot survive well without human help. Mithuns reproduce independently of humans, in the forest, so their domestication is questionable. Such animals are “wild” rather than “feral” (escaped from domestication and become wild). Ma et al., “Comparative Transcriptome Analyses”; Chen et al., “Draft Genome”; Ahrestani “Bos frontalis”, 4, 8: Li et al., “Large-Scale Chromosomal Changes”.

- why the area of mithun distribution is so much more restricted than that of both gaur and domestic cattle;

- why the mithun is genetically adapted to withstand hypoxia at high altitudes up to 4,000 m and cannot thrive at altitudes below 200 m — unlike the gaur, which roams from sea level to 2,500 m; and

- why the physical appearance of the mithun (e.g., the shape of the horns, body size) is both very distinctive and very stable over generations.

Castelló, Bovids, 628–629. Mithuns may have a dark brown or piebald coat, often with white lower legs. Their horns do not curve upwards like a gaur’s.

On the genetic adaptations that allow mithuns to live in high-mountain environments, see Ma et al., “Comparative Transcriptome Analyses”.

In Butler’s words (“Rough Notes”, 332), “the forest-clad shades of the lower hills”.

Geng et al., “Prioritizing Fodder Species”.

The term Mithun Country is taken from Simoons and Simoons (A Ceremonial Ox), who spell it “Mithan Country”. This pathbreaking book is still the single-most informative overview on the mithun.

I follow Fisher’s (Environmental History, 1) working definition of environmental history as “vital patterns of interactions among humans, other living beings, and the material world.”

Mithuns share their habitat with humans speaking well over a hundred different languages and holding many distinct ethnic and religious beliefs. Several are mentioned in Dorji et al. “Mithun”. It is common in Indian social-science literature to refer unselfconsciously to these ethnic groups as “tribes” — a term anchored in the Indian constitution. This is not the case in Bhutan, China, Bangladesh, and Myanmar For an introductory map, see http://www.muturzikin.com/cartesasiesudest/sud.htm.

Blench, “Contribution of Linguistics”, 80–82, 106.

Several parts of the mithun habitat were claimed by British India and China but remained what the British called “unadministered”. These regions were ruled by numerous small polities that continued precolonial styles of governance and had no use for literacy. Some were buffers between Assam, Tibet and Bhutan (the North-East Frontier Tracts) and between northern and eastern Burma and China (the Hukawng Valley, “the Triangle”, parts of the Naga country, and the Wa region of the Shan hills). Others were surrounded by British Indian territory but were, up to the 1940s, too dangerous for British troops to conquer (for example, an area between Arakan, Bengal, the Lushai hills and the Chin hills). See, for example, Hutton, Diaries.

Sarma and Zoliana, Changing Affinities, 146–47.

One way of defining animism is as a worldview that assumes that not only humans, but also nonhuman animals, plants, and other parts of the environment are sentient and therefore share obligations. In Mithun Country, there were considerable differences in mithun lore and sacrificial practices among ethnic and religious groups. Sarma and Zoliana, Changing Affinities, 75–80. In Bangladesh, mithun sacrifices have also been reported among Muslims. Faruque et al., “Present Status of Gayal”, 81; Kabir, “Report on Case Study”.

Hutton, Diaries, 13; Sarma and Zoliana, Changing Affinities, 79–80. Mithun sacrifices were essential markers of both human lifecycle events and the agricultural cycle. For example, in what is now Arunachal Pradesh (India), a bridegroom would have to work for the bride’s parents during a planting season, after which a wedding was arranged in which the village religious specialist sacrificed a mithun and a “portion of the blood and a small part of each limb is taken into the jungle and left as an offer to the spirits.” “Affairs on the North-East Frontier”, 49.

Elwin, Myths, 4, 18, 89. The primeval importance of mithuns was also attested to by the story of the sun, in a quarrel with the moon, throwing mithun dung at it, causing the dark spots that are still visible from earth. Elwin, Myths, 52.

Elwin, Myths, 5, 8–9.

Elwin, Myths, 24–25.

Elwin, Myths, 86–88.

In northern Mithun Country humans considered the mithun as close kin because it originated in strife between siblings, resulting in one becoming human and the other a mithun (e.g. Elwin, Myths, 397–400). Among the many stories about the origins of the mithun, one is associated with brother–sister incest. Elwin, Myths, 98, 352, 394; Blackburn, Himalayan Tribal Tales, 119–22, 265; Pachuau and Van Schendel, Entangled Lives, 96–97. Mithuns were treated as equal to humans in many other stories as well (Sarma and Zoliana, Changing Affinities, 75–80). For reflections on interspecies kinship and personhood regarding another bovine, the yak, see Wouters, “Relatedness, Trans-species Knots”.

Aisher, “Through ‘Spirits’”, 191.

Humans sometimes interpreted such a disappearance as a mithun having been abducted by spirits. Aisher, “Through ‘Spirits’”, 236–37.

Faruque et al., “Present Status of Gayal”, 79–80; Bareigts, Les Lautu, 88.

In many societies in the region, individual humans consider themselves to be associated with, or own, individual free-roaming mithuns. Aiyadurai, “‘Tigers are our Brothers’”, 77–78, 110.

The richness of mithun lore makes the region excellently suited to gaining deeper insights into local perceptions of wildness. So far, linkages with comparative studies of the meaning of wildness and domestication in different cultures and historical circumstances have been rather tenuous. Recent scholarly research in Mithun Country challenges the wildness/domestication dichotomy and could benefit from stronger comparative perspectives. For example, Norton identifies a stage/practice that she calls “taming” and explains the Caribbean concept of iegue, “an animal whom one feeds.” She rejects the teleological assumption that this practice necessarily leads to domestication. Norton, The Tame and the Wild. See Aisher, “Through ‘Spirits’”; Aiyadurai, “‘Tigers are our Brothers’”; Blackburn, Himalayan Tribal Tales; Sakhong, In Search of Chin Identity; Jackson, Mizo Discovery; Wouters, “Relatedness”.

Indigenous understandings complicate the wild/domestic dichotomy. A detailed study of a group in northern Mithun Country argues that they distinguish human-reared animals (chickens, pigs, etc.; the animals of the village) and spirit-reared animals (the animals of the forest). The mithun’s power is based on it being the only intermediary: the only living being that habitually moves between these two parallel worlds of the forest and the village. Aisher, Through ‘Spirits’”, 307–8.

Sometimes these parallel worlds are conceived as “human” and “sky”. As one observer explained the complex entanglement: “the mithun of men is associated with the sky spirits, while the souls of men are conversely bound up with the mithun of the sky, so that when a mithun dies on earth a spirit dies in the sky, and when a man dies, it means that the sky spirits have sacrificed a mithun.” Hutton, Diaries, 13.

Aisher (“Through ‘Spirits’”) contains detailed descriptions of the indispensable cosmological role that (souls of) mithuns play — and the notion of human and mithun souls living parallel existences — among the Nyishi of northern Mithun Country. See Sarma and Zoliana, Changing Affinities, 78.

Unlike mithuns, these lesser sacrificial animals were domestic animals: chickens, pig(let)s,

goats, dogs, and so on. They were needed for minor occasions, for example to mollify forest spirits before clearing a field for slash-and-burn agriculture. Bareigts, Les Lautu.Aisher, “Through ‘Spirits’”, 111, 120; 126. It is important to realize that the cultural significance of the mithun is based on completely different cosmological assumptions than that of a better known “sacred” bovine of South Asia, the domesticated cow. In the cosmology of Hinduism (a religion that was of no significance among mithun-oriented mountain societies), avoiding beef was a dominant doctrine. In Mithun Country, consuming sacrificial mithun meat formed the core of community feasts. For an introduction to the literature on human-domestic-cow relations in Hindu communities in South Asia, see Adcock and Govindrajan, “Bovine Politics”.

Bareigts, Les Lautu, 158–59. My translation.

“Mithun gravitate towards the dense, often dark, tropical, subtropical and temperate forests surrounding the village. Here, away from the village, they feed, breed and bear offspring. This habitual migration between human and uyu [spirit] domains only serves to reinforce their powerful cosmological significance as sacrificial animals par excellence.” Aisher, “Voices of Uncertainty”, 490.

Fraser and Fraser, Mantles of Merit, 69. See Lehman, Structure of Chin Society, 180; Sakhong, In Search of Chin Identity, 76.

As far as I know, these carefully preserved skulls — which remain spiritually significant for generations — have not yet been used as sources of animal osteobiography (the study of life histories through skeletal remains), which could throw light on the hidden histories of mithun foraging and breeding behaviour, as well as on their geographical movements.

Mayirnao and Khayi, “Decolonosing Feasts”; Yekha-ü and Marak, “Elicüra”.

Woodward, “Gifts”.

In the words of one woman’s song: “To kill a mith[u]n and erect a wall of decorative [design to celebrate it] is the highest honour in our land.” Sakhong, In Search of Chin Identity, 72.

Woodward “Gifts for the Sky People”, 221. See Malsawmliana, “Socio-Economic Importance”; Rawlins, “On the Manners”; Shakespear, “The Lushais”; Fraser and Fraser, Mantles of Merit, 30–31; Head, Hand Book. As Lehman (Structure of Chin Society, 40) put it: “It is an animal of great symbolic value, the beast of choice in major sacrifices, the common measure of value in exchange transactions including bride price, and an animal figuring prominently in metaphors concerned with beauty, strength, and so forth.”

Fürer-Haimendorf, Konyak Nagas, 60. Alcohol was ceremoniously gulped from mithun horns, and “powder flasks of gayal (the mithun) horn are beautifully polished and inlaid with silver or ivory“ (Shakespear, History of the Assam Rifles, 77). The tough mithun hide was used for shields. Macrae, “Account of the Kookies”, 186.

Tzüdir, “Appropriating the Ao Past”, 284–85.

Achumi, “‘Tell Them Our Story’”, 9.

Pachuau and Van Schendel 2015, Camera, 59–86.

Brauns and Löffler, Mru, 130. See also Pachuau and Van Schendel, Camera, 177–81.

According to Brauns and Löffler (Mru, 130), “[t]he Christian Bawm [of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh] […] pool their resources in order to purchase a gayal [mithun], and the animal is then consumed by the entire village at Christmastime”.

For example, mithun intimacy provided a link between several groups with mutually unintelligible languages in Northeast India as they sought to foreground the umbrella concept of “Naga”. The mithun emerged as a badge of Naga connectedness and distinctiveness.

A mithun-head tattoo, created by contemporary tattoo artist Mo Naga (Moranngam Khaling), appears on anthropologist Lars Krutak’s website: https://www.larskrutak.com/mo-naga-naga-tattoo-revival/. Mo Naga’s “Neo-Naga” design was inspired by a Konyak Naga woodcarving and a Maram Naga house painting. See also Krutak, “Neo-Naga”; Hutton, Diaries, 23.

For example, in the poem “Let’s Hope, Anyway”, by Yumlam Tana, a poet who lives in Arunachal Pradesh (India): “Some day / You will come back to me / As does the Bos frontalis / Piebald, white-stocked, white-horned and white-faced / Returns to its salt licks / Tucked away in the core of cool earth and green copses. / Maybe / I will lead you / Salt-licking / To my house / And it will be your second coming.”

Before 1972 Arunachal Pradesh (contested between India and China) was known as the North East Frontier Area (NEFA). The mithun was NEFA’s logo, too. Tellingly, the state emblem of Nagaland shows the mithun as well as the state motto “Unity”. Longkumer, “Representing the Nagas”, 169–70.

By contrast, India’s “Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972” still classifies the mithun as “the domesticated form” of the gaur.

Lotha, The Raging Mithun.

In China, animal sacrifices were forbidden in 1950. Although bovine sacrifices were well-known in the mountains of northwestern Yunnan (China), it is not clear if the mithuns living there were used. Gros (“Cultes”) mentions domestic cattle being used in feasts of merit very similar to the mithun sacrifices described for other parts of Mithun Country.

This notion of wildness is also reflected in the fact that several zoos around the world keep mithuns in their collections. https://zooinstitutes.com/animals/domestic-gayal-211/ (accessed 16 February 2024). As early as the 1900s, an attempt was made to stock one or more European zoos with mithuns: a 1916 note, which sought to secure mithuns from the Lushai hills for an American ranch in the Philippines, mentioned a “German [who] brought down 30 or 40 gayal [mithun ...] about 10 or 12 years ago and shipped them from Chittagong for the Kaiser.” Jackson, Mizo Discovery, 81.

Definitions of domestication differ. The mere human use of plants and animals does not imply their domestication. Domestication can be said to result from selective breeding and physical alteration for specific characteristics. Pachuau and Van Schendel, Entangled Lives, 41–42.

Project Maje, “Mithuns Sacrificed”.

“Mithun”; https://nrcmithun.icar.gov.in/. This could create conflicts between locals and livestock scientists. Sarma and Zoliana, Changing Affinities, 107–12.

Dorji et al., “Mithun”, 1735–36; Uzzaman et al., “Semi-domesticated and Irreplaceable”; Project Maje, “Mithuns Sacrificed”.

Half the mithuns brought to a “research farm” in Yunnan (China) died within months (He et al., “Superovulatory”). There is a history of mithuns perishing after being brought to the Chittagong lowlands in Bangladesh. For an “artificial reproduction center”, set up in Naikhangchhari (elevation 19 m.), see Uzzaman et al., “Semi-domesticated and Irreplaceable”, 1370.

Khan et al. “Semi-Intensive”.

ICAR-National Research Centre on Mithun, “Semi-intensive”; Management Practices.

Dorji et al., “Mithun”, 1733–34. See Cram et al.; Van der Wal et al.

In China, the number of mithuns has recently been growing to over 20,000 in reforested areas. Dulong Niu; “Yúnnán gòngshān xiàn dúlóngjiāng xiāng shēngtài fúpín de shēngdòng shíjiàn” [The vivid practice of ecological poverty alleviation in Dulongjiang Township, Gongshan County, Yunnan]. Ministry of Ecology and the Environment of the People’s Republic of China, 11 September 2019. https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk15/201909/t20190911_733388.html.

Another factor may be that more people leave villages for education or non-agricultural jobs, so they have less time to cultivate their links with mithuns. On the other hand, there may be technological innovations (such as mithun trackers fitted on collars) that could make it easier to maintain these links. Sarma and Zoliana, Changing Affinities, 107–8, 149–51.

Sarma and Zoliana, Changing Affinities.

Scholars propose that wider regional perspectives can also be applied to these cultures. Thus, Blackburn (“Oral Stories”) suggests that the oral histories of Mithun Country were connected and that they formed a larger “culture area” stretching from northeast India to southwest China. Another wider framing is “the New Himalayas” — the anthropogenically impacted Himalayas since the early modern era, characterized by “the transboundary, the indigenous and the animist”. Smyer Yü, “Situating Environmental Humanities”, 4.

Mithun territory coincides with none of the “terrestrial ecoregions” delineated by the World Wildlife Fund. It covers parts of no less than nine of them: the Northern Triangle subtropical forests, the Northern Triangle temperate forests, the Northeast India–Myanmar pine forests, the Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests, the Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests, the Mizoram–Manipur–Kachin rain forests, the Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests, the Lower Gangetic plains moist deciduous forests, and the Myanmar coastal rain forests. Dinerstein et al., “An Ecoregion-Based Approach”.

Mittermeier et al., “Global Biodiversity”. For a map, see https://www.e-education.psu.edu/geog30/book/export/html/393 (accessed 26 February 2024).

Both Kauffmann (“Landwirtschaft”, 62–64, 110) and Simoons and Simoons (A Ceremonial Ox, 6–7) provide maps of mithun distribution by ethnic group in the 1930s.

Smyer Yü and Dean, Yunnan–Burma–Bengal Corridor Geographies.

Devi et al. (“Revisit of the Taxonomic Status”, 6) assert that “our generated sequence of B. frontalis [mithun] showed a distinct cluster and confirms that B. frontalis is not the domesticated form of B. gaurus [gaur], but rather a distinct species under the genus Bos […]. Many animal taxonomists mistook it as a domesticated type of Indian gaurus due to their similarity in appearance.”

As humans, we are unable to fathom the intentions of nonhuman animals or see the world “through their eyes”. Attempts to do so have been dismissed as pretentious ventriloquizing. But we can understand how the actions of nonhuman animals affect human–nonhuman relationships. See Swart, “Animals in African History”, 2.

Humans were not imagined as being “outside” nature, although in some local cosmologies a clear distinction was made between the parallel worlds of the village and the forest; in others the overarching unity of the universe was foregrounded. Woodward, “Gifts”; Aisher, “Through ‘Spirits’”.

Colonial rule commenced in some parts of Mithun Country (Arakan/Rakhine and Assam) in the 1820s and lasted over 120 years. Upper Burma was incorporated in British India in the 1880s. But other parts of Mithun Country (in what are now Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Kachin State, and an area near the Bangladesh/India/Myanmar trijunction) remained self-governing throughout — and sometimes well beyond the collapse of the colonial state (in 1947–48) and the emergence of its successor states. Areas in Yunnan were never part of a colonial state. Their history is usually framed in terms of Chinese dynasties (Ming, Qing), and their successor republics, but such framing makes no sense for other parts of Mithun Country.

Pachuau and Van Schendel, Entangled Lives, 7–14, 64.

Das, “From Millet to Rice”.

In this region, environmental historians could explore how best to apply these levels of interspecies temporality by considering partly overlapping interspecies time periods based on, say, the “mautam” corridor (where bamboo flowering causes human famines); valuable medicinal fungi or plants (caterpillar fungus (Cordyceps sinensis) and Mishmi teeta (Coptis teeta)); “rediscovered” species (the Mishmi wren-barbler, Spelaeornis badeigularis); or invasive species such as water hyacinth (Pontederia crassipes) and shrub verbena (Lantana camara). Pachuau and Van Schendel, Entangled Lives, 28, 221, 239; Weckerle et al., “People, Money”; King and Sonahue, “Rediscovery”; Iqbal, “Fighting with a Weed”; Rai and Singh, “Lantana camara Invasion”.

For example, Van Schendel, “Non-Human Labour History?”

Smyer Yü, “Environmental Edging”; Cederlöf and Van Schendel, Flows and Frictions.

As in the case of a Naga group’s traditional boundary with the Ahom state, in today’s Assam. Agrawal and Kumar, Numbers in India’s Periphery, 113.

Pachuau and Van Schendel, Entangled Lives, 11–12.

Morrison, “Conceiving Ecology”, 42.

Works Cited

Achumi, Ilito H. “‘Tell Them Our Story’: Memories of the Sumi Naga Labour Corps in World War I.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 46, no. 1 (2023): 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2023.2143653

Adcock, Cassie, and Radhika Govindrajan. “Bovine Politics in South Asia: Rethinking Religion, Law and Ethics.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 42, no. 6 (2019): 1095–1107.

“Affairs on the North-East Frontier.” Foreign and Political Department, Secret E Branch, Government of India, Proceedings (December 1914) 156–34. National Archives of India, New Delhi.

Agrawal, Ankush, and Vikas Kumar. Numbers in India’s Periphery: The Political Economy of Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Ahrestani, Farshid S. “Bos frontalis and Bos gaurus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae).” Mammalian Species 50, no. 959 (2018): 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/mspecies/sey004

Aisher, Alexander. “Through ‘Spirits’: Cosmology and Landscape Ecology among the Nyishi Tribe of Upland Arunachal Pradesh, Northeast India”. PhD thesis, University College London, 2006.

Aisher, Alexander. “Voices of Uncertainty: Spirits, Humans and Forests in Upland Arunachal Pradesh, India. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 30, no. 3 (2007), 479–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856400701714088

Aiyadurai, Ambika. “‘Tigers are our Brothers’: Understanding Human-Nature Relations in the Mishmi Hills, Northeast India.” PhD thesis, University of Singapore, 2016.

Baig, Mumtaz, et al. 2013. “Mitochondrial DNA Diversity and origin of Bos frontalis.” Current Science 104, no. 1 (2013): 115–20.

Barbe, M. “Some Account of the Hill Tribes in the Interior of Chittagong, in a Letter to the Secretary of the Asiatic Society.” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 14, no. 1 (1845): 380–91.

Bareigts, André. Les Lautu: Contribution à l’étude de l’organisation sociale d’une ethnie chin de Haute-Birmanie. Paris: SELAF, 1981.

Bhattacharya, Neeladri, and Joy L. K. Pachuau, eds. Landscape, Culture, and Belonging: Writing the History of Northeast India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Blackburn, Stuart. Himalayan Tribal Tales: Oral Tradition and Culture in the Apatani Valley. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

Blackburn, Stuart. “Oral Stories and Culture Areas: From Northeast India to Southwest China.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 30, no. 3 (2007): 419–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856400701714054

Blench, Roger. “The Contribution of Linguistics to Understanding the Foraging/Farming Transition in Northeast India.” In 50 Years after Daojali-Hading, edited by Tiatoshi Jamir and Manjil Hazarika, 99–109. New Delhi: Research India Press, 2014.

Bonnell, Jennifer, and Sean Kheraj, eds. Traces of the Animal Past: Methodological Challenges in Animal History. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2022.

Boomgaard, Peter. Southeast Asia: An Environmental History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2007.

Brauns, Claus-Dieter, and Lorenz G. Löffler. Mru: Hill People on the Border of Bangladesh. Translated by Doris Wagner-Glenn. Basel: Springer Basel.

Butler, John. “Rough Notes on the Angámi Nágás and their Language.” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 44, no. 1 (1875): 308–46.

Castelló, José R. Bovids of the World: Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Cederlöf, Gunnel, and Willem van Schendel, eds. Flows and Frictions in Trans-Himalayan Spaces: Histories of Networking and Border Crossing. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2022.

Chakrabarti, Ranjan, ed. Critical Themes in Environmental History of India. New Delhi: Sage, 2020.

Chen, Yan, Tianlu Zhang, Ming Xian, et al. “A Draft Genome of Drung Cattle Reveals Clues to Its Chromosomal Fusion and Environmental Adaptation.” Communications Biology 5 (2022): 353. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03298-9

Cram, Dominic L., Jessica E. M. van der Wal, Natalie T. Uomini, et al. “The Ecology and Evolution of Human–Wildlife Cooperation.” People and Nature 4, no. 4 (2022): 841–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10369

Cuvier, Frédéric. Supplément à l’histoire naturelle générale et particulière de Buffon. Vol. 1: Mammifères. Paris: F. D. Pillot, 1831.

Das, Debojyoti. “From Millet to Rice: The Politics of the New Faith and Time Discipline among Borderland Communities in Eastern Nagaland.” Asian Ethnology 79, no. 2 (2020): 377–94.

Devi, Ningthoujam Neelima, Bihsal Dahar, Prasanta Kumar Bera, Yashmin Choudhury, and Sankar Kumar Ghosh. “Revisit of the Taxonomic Status of Bos Genus with Special Reference to North Eastern Hilly Region of India.” Animal Gene 27 (2023): 200143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.angen.2022.200143

Dinerstein, Eric, David Olson, Anup Joshi, et al. “An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm.” BioScience 67, no. 6 (2017): 534–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix014

Dorji, Tashi, Jigme Wangdi, Yi Shaoliang, Nakul Chettri, and Kesang Wangchuk. “Mithun (Bos frontalis): The Neglected Cattle Species and Their Significance to Ethnic Communities in the Eastern Himalaya — A Review.” Animal Bioscience 34, no. 11 (2021): 1727–38. https://doi.org/10.5713/ab.21.0020

Dulong Niu [Mithun]. [Lushui]: People’s Government of Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, 2023.

Elwin, Verrier. Myths of the North-East Frontier of India. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1958.

Evans, G.P. Big-Game Shooting in Upper Burma. London: Longmans, Green, 1911.

Faruque, M.O., et al. “Present Status of Gayal (Bos frontalis) in the Home Tract of Bangladesh.” Bangladesh Journal of Animal Science 44, no. 1 (2015): 75–84. https://doi.org/10.3329/bjas.v44i1.23147

Fisher, Michael H. An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Fraser, David W., and Barbara G. Fraser. Mantles of Merit: Chin Textiles from Myanmar, India and Bangladesh. Bangkok: River Books, 2005.

Fürer-Haimendorf, Christoph von. The Konyak Nagas: An Indian Frontier Tribe. New York and London: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969.

Geng, Yanfei, Guoxiong Hu, Sailesh Ranjitkar, et al. “Prioritizing Fodder Species Based on Traditional Knowledge: A Case Study of Mithun (Bos frontalis) in Dulongjiang Area, Yunnan Province, Southwest China.” Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 13 (2017): 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0153-z

Gros, Stéphane. “Cultes de fertilité chez les Drung du Yunnan (Chine)”. Moussons 19 (2012): 111–136. https://doi.org/10.4000/moussons.1264

He, Zhan Xing, Yoko Sato, Ji Cai Zhang, et al. “Superovulatory Response and Pregnancy after Interspecies Transfer of Embryos in Semi-wild Dulong (Bos frontalis) — Short Communication.” Veterinarski Arhiv 84, no. 2 (2014), 183–88. https://hrcak.srce.hr/119052

Head, W. R. Hand Book on the Haka Chin Customs. Rangoon: Office of the Superintendent, Government Printing, Burma, 1917.

Hill, Christopher V. South Asia: An Environmental History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2008.

Hutton, J. H. Diaries of Two Tours in the Unadministered Area East of the Naga Hills. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press, 1929.

ICAR-National Research Centre on Mithun. Management Practices for Improved Mithun (Bos frontalis) Husbandry. Medziphema, Nagaland: ICAR-NRC on Mithun, 2020. https://nrcmithun.icar.gov.in/node/704

ICAR-National Research Centre on Mithun. Mithun (Bos frontalis): The Unique Bio-Resource of North East India. Medziphema, Nagaland: ICAR-NRC on Mithun, 2020. https://nrcmithun.icar.gov.in/node/701

ICAR-National Research Centre on Mithun. “Semi-intensive Mithun Rearing Units.” Mithun Digest 17, no. 1 (2021): 14. https://nrcmithun.icar.gov.in/node/909

Iqbal, Iftekhar. “Fighting with a Weed: Water Hyacinth and the State in Colonial Bengal, c. 1910–1947.” Environment and History 15, no. 1 (2009): 35–59. https://doi.org/10.3197/096734009X404653

Jackson, Kyle. The Mizo Discovery of the British Raj: Empire and Religion in Northeast India, 1890–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Kabir, Shariear. “A Report on Case Study of a Gayal Farm Located at Padua, Sukhbilash Rangunia, Chattogram.” Chattogram: Chattogram Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, 2020. http://dspace.cvasu.ac.bd/jspui/handle/123456789/451

Kauffmann, Hans-Eberhard. “Landwirtschaft bei den Bergvölkern von Assam und Nord-Burma.” Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 66, no. 1/3 (1934): 15–111. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25839470

Kauffmann, Hans-Eberhard. “Die Bedeutung des Dorftores bei den Angami-Naga.” Geographica Helvetica 10, no. 2 (1955): 84–95. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-10-84-1955

Kean, Hilda, and Philip Howell, eds. The Routledge Companion to Animal–Human History. London: Routledge, 2019.

Khan, Meraj Haider, et al. Semi-Intensive Mithun Farming: Success Stories Under Tribal Sub Plan (2016–2021). Medziphema, Nagaland: ICAR-National Research Centre on Mithun, 2022.

King, Ben, and Julian P. Donahue. “The Rediscovery and Song of the Rusty-Throated Wren Babbler Spelaeornis badeigularis”. Forktail no. 22 (2006): 113–15.

Krutak, Lars. “Neo-Naga.” TätowierMagazin July 2015: 50–54.

Lambert, Aylmer Bourke. “Description of Bos Frontalis, a new Species, from India.” Transactions of the Linnean Society 7, no. 1 (1804): 57–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1804.tb00280.x

Lambert, Aylmer Bourke. “Further Account of the Bos Frontalis.” Transactions of the Linnean Society 7, no. 1 (1804): 302–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1804.tb00296.x

LaPolla, Randy J., and David Sangdong. Rawang-English-Burmese Dictionary (A Tibeto-Burman Language Spoken in Myanmar). Singapore: privately published, 2015. https://www.rawang.org/files/Rvwang-English-Burmese%20dictionary.pdf

Lehman, F. K. The Structure of Chin Society: A Tribal People of Burma Adapted to a Non-Western Civilization. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1963.

Li, S. P., H. Chang, G. L. Ma, and H. Y. Cheng. “Molecular Phylogeny of the Gayal in Yunnan China Inferred from the Analysis of Cytochrome b Gene Entire Sequences.” Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Science 21, no. 6 (2008): 789–93. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2008.70637

Li, Yan, et al. “Large-Scale Chromosomal Changes Lead to Genome-Level Expression Alterations, Environmental Adaptation, and Speciation in the Gayal (Bos frontalis).” Molecular Biology and Evolution 40, no. 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msad006

Longkumer, Arkotong. “Representing the Nagas: Negotiating National Culture and Consumption.” In Bhattacharya and Pachuau, Landscape, Culture, and Belonging, 151–75.

Lotha, Abraham. The Raging Mithun: Challenges of Naga Nationalism. Kohima: Barkweaver, 2013.

Ma, Jun, et al. “Comparative Transcriptome Analyses of Gayal (Bos frontalis), Yak (Bos grunniens), and Cattle (Bos taurus) Reveal the High-Altitude Adaptation.” Frontiers in Genetics 12 (2022): 778788. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.778788

Macrae, John. “Account of the Kookies or Lunctas.” Asiatic Researches 7 (1803): 183–98.

Malsawmliana. “Socio-Economic Importance of Sial (Mithun) in Traditional Mizo Society.” Historical Journal Mizoram 21 (2021): 41–53.

Mayirnao, Shaokhai, and Sinalei Khayi. “Decolonising Feasts of Merit: Reasoning Marān Kasā from a Tangkhul Naga Perspective”. Asian Ethnicity 24, no. 2 (2023): 258–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2022.2089093

Mills, J. P. The Ao Nagas. London: Macmillan, 1926.

Mittermeier, Russell A., Will R. Turner, Frank W. Larsen, Thomas M. Brooks, and Claude Gascon. “Global Biodiversity Conservation: The Critical Role of Hotspots.” In Biodiversity Hotspots: Distribution and Protection of Conservation Priority Areas, edited by Frank E. Zachos, and Jan Christian Habel, 3–22. Heidelberg: Springer, 2011.

Miyamoto, Mari, Jan Magnusson, and Frank J. Korom. “Animal Slaughter and Religious Nationalism in Bhutan.” Asian Ethnology 80, no. 1 (2021): 121–45.

Morrison, Kathleen D. “Conceiving Ecology and Stopping the Clock: Narratives of Balance, Loss, and Degradation.” In Shifting Ground: People, Animals, and Mobility in India’s Environmental History, edited by Mahesh Rangarajan and K. Sivaramakrishnan, 39–60. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Mukherjee, Sabyasachi, Anupama Mukherjee, Sanjeev Kumar, et al. “Genetic Characterization of Endangered Indian Mithun (Bos frontalis), Indian Bison/Wild Gaur (Bos gaurus) and Tho-tho Cattle (Bos indicus) Populations Using SSR Markers Reveals Their Diversity and Unique Phylogenetic Status.” Diversity 14, no. 7 (2022): 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14070548

Norton, Marcy. The Tame and the Wild: People and Animals after 1492. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2024.

Pachuau, Joy L.K., and Willem van Schendel. The Camera as Witness: A Social History of Mizoram, Northeast India. Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Pachuau, Joy L.K., and Willem van Schendel. Entangled Lives: Human-Animal-Plant Histories of the Eastern Himalayan Triangle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Passah, Sajeki. Pnar–English Dictionary. Jowai: Pnar Printers and Publishers, 2013.

Pearson, J. T. “Memorandum on the Gaur and Gayal.” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 6, no. 1 (1837): 225–30.

Perlin, Ross. “A Grammar of Trung.” Himalayan Linguistics (2020). https://doi.org/10.5070/H918244579

Post, Mark. W. “On Reconstructing Ethno-linguistic Prehistory: The Case of Tani.” In Crossing Boundaries: Tibetan Studies Unlimited, edited by Diana Lang, Jarmila Ptáčková, Marion Wettstein, and Mareike Wulff, 311–40. Prague: Academia, 2022.

Project Maje. “Mithuns Sacrificed to Greed: The Forest Ox of Burma’s Chins.” Portland, OR: Project Maje, 2004. https://www.projectmaje.org/mithuns.htm

Rai, Prabhat Kumar, and M. Muni Singh. “Lantana camara Invasion in Urban Forests of an Indo-Burma Hotspot Region and Its Ecosustainable Management Implication through Biomonitoring of Particulate Matter.” Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity 8, no. 4 (2015): 375–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japb.2015.09.003

Rainey, R. M. “Notes on the Chinboks, Chinbons, and Yindus of the Chin Frontier of Burma.” Indian Antiquary 21 (1892): 215–24.

Rangarajan, Mahesh, and K. Sivaramakrishnan, eds. India’s Environmental History from Ancient Times to the Colonial Period: A Reader. 2 vols. Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2012.

Rangarajan, Mahesh, and K. Sivaramakrishnan, eds. Shifting Ground: People, Animals, and Mobility in India’s Environmental History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Rawlins, John. “On the Manners, Religion, and Laws of the Cucis, or Mountaineers of Tipra.” Asiatic Researches 2 (1799): 187–93.

Roscher, Mieke, André Krebber, and Brett Mizelle, eds. Handbook of Historical Animal Studies. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2021.

Sakhong, Lian H. In Search of Chin Identity: A Study in Religion, Politics and Ethnic Identity in Burma. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2003.

Sarma, Abhishruti, and Joseph Zoliana. Changing Affinities: Ecologies of Human–Mithun Relationships in Northeast India. Guwahati: North Eastern Social Research Centre, 2023.

Shakespear, John. “The Lushais and the Land They Live In.” Journal of the Society of Arts 43, no. 2201 (January 1895): 167–185. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41334168

Shakespear, L. W. History of the Assam Rifles. London: Macmillan, 1929.

Sharma, H. Surmangol. Learners’ Manipuri–English Dictionary. Imphal: Sangam Book Store, 2006.

Simoons, Frederick J., and Elizabeth S. Simoons. A Ceremonial Ox of India: The Mithan in Nature, Culture and History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968.

Singh, U Nissor. Khasi–English Dictionary. Shillong: Eastern Bengal and Assam Secretariat Press, 1906.

Smyer Yü, Dan. “Situating Environmental Humanities in the New Himalayas: An Introduction.” In Smyer Yü and De Maaker, Environmental Humanities in the New Himalayas, 1–24.

Smyer Yü, Dan. “Environmental Edging of Empires, Chiefdoms, and States: Corridors as Transregions.” In Smyer Yü and Dean, Yunnan–Burma–Bengal Corridor Geographies, 46–67.

Smyer Yü, Dan, and Erik de Maaker, eds. Environmental Humanities in the New Himalayas: Symbiotic Indigeneity, Commoning, Sustainability. London: Routledge, 2021.

Smyer Yü, Dan, and Karin Dean, eds. Yunnan–Burma–Bengal Corridor Geographies: Protean Edging of Habitats and Empires. London: Routledge, 2022.

Swart, Sandra. “Animals in African History.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, edited by Thomas T. Spear. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.443

Tenzin, Sangay, Jigme Dorji, Tashi Dorji, and Yoshi Kawamoto. “Assessment of Genetic Diversity of Mithun (Bos frontalis) Population in Bhutan Using Microsatellite DNA Markers.” Animal Genetic Resources 59 (2016): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2078633616000072

Tzüdir, Lanusangla. “Appropriating the Ao Past in a Christian Present.” In Bhattacharya and Pachuau, Landscape, Culture, and Belonging, 265–93.

Uzzaman, Rasel, Shamsul Alam Bhuiyan, Zewdu Edea, and Kwan-Suk Kim. “Semi-domesticated and Irreplaceable Genetic Resource Gayal (Bos frontalis) Needs Effective Genetic Conservation in Bangladesh: A Review.” Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Science 27, no. 9 (2014): 1368–72. http://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2014.14159

Van der Wal, Jessica E. M., Claire N. Spottiswoode, Natalie T. Uomini, Mauricio Cantor, Fábio G. Daura-Jorge, Dominic L. Cram, et al. “Safeguarding Human–Wildlife Cooperation.” Conservation Letters 15, no. 4 (2022): e12886. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12886

Van Schendel, Willem. “Non-Human Labour History? Three Short Questions.” Notebooks: The Journal for Studies on Power 2, no. 2 (2023): 189–99. https://doi.org/10.1163/26667185-bja10035

Van Schendel, Willem, Wolfgang Mey, and Aditya Kumar Dewan. The Chittagong Hill Tracts: Living in a Borderland. Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2000.

Wang, Ming-Shan, Yan Zeng, Xiao Wang, et al. “Draft Genome of the Gayal, Bos frontalis.” GigaScience 6, no 11 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/gix094

Weckerle, Caroline S., Yongping Yang, Franz K. Huber, and Qiaohong Li. “People, Money, and Protected Areas: The Collection of the Caterpillar Mushroom Ophiocordyceps sinensis in the Baima Xueshan Nature Reserve, Southwest China”. Biodiversity and Conservation 19 (2010): 2685–98.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-010-9867-0Wilcox, R. “Memoir of a Survey of Asam and the Neighbouring Countries, Executed in 1825-6-7-8.” Asiatic Researches 17 (1832): 314–469.

Woodward, Mark R. “Gifts for the Sky People: Animal Sacrifice, Headhunting and Power among the Naga of Burma and Assam.” In Indigenous Religions: A Companion, edited by Graham Harvey, 219–29. London: Cassell, 2000.

Wouters, Jelle J. P. 2021. “Relatedness, Trans-species Knots and Yak Personhood in the Bhutan Highlands.” In Smyer Yü and De Maaker, Environmental Humanities in the New Himalayas, 27–42.

Yekha-ü and Queenbala Marak. “Elicüra: The ‘Feasts of Merit’ Shawl of the Chakhesang Naga of Northeast India.” The Oriental Anthropologist 21, no. 1 (2021): 138–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972558X21990790

Yumlam Tana. “Let’s Hope Anyway.” NetLit Review: The Seven Sisters Post Literary Review, 3 June 2012. https://nelitreview.tumblr.com/post/24306633566/poems-by-yumlam-tana