Don’t Let Them Eat Horse

Email: cgunderm@mtholyoke.edu

Humanimalia 14.2 (Spring 2024)

I first came across Kari Weil’s work when, in the early 2010s, I was putting together the syllabus for my first college course in Critical Animal Studies. Grappling with how to teach the animal liberation and abolitionism paradigms of such foundational figures as Peter Singer, Tom Regan, and Gary Francione, I found in Weil’s 2012 book Thinking Animals one of the clearest, most compelling discussions of what frustrated me about this discourse: that it was so utterly removed from real experience with animals. When figures like Francione speak of the elimination of all domestic animals as the solution to human domination, Weil writes, we are not being led towards a reasonable outcome, but rather “the law professor’s sacrifice of the animals for his ‘idea of the world.’”1 Later I learned that Weil was, like myself, a horse person, which further confirmed that I needed to follow her work.

The format of this review is much too brief to do justice to the breadth of topics, fields, and disciplines covered in Weil’s fascinating new book, Precarious Partners: Horses and Their Humans in Nineteenth-Century France. It runs the gamut from visual art to public health debates concerning the slaughter of horses; from military history to the circus and city street as novel sites of a horse-centred entertainment culture; from the history of science to science’s refutation of magnetism, all the while peering through a feminist lens to parse how precisely horses figured in the construction and negotiation of class and gender norms in nineteenth-century France. The book’s introduction, “The Most Beautiful Conquest of Man?” theorizes the centrality of horses as partners (and perhaps mirrors?) to humans by way of a foundational feminist text, Gayle Rubin’s “The Traffic in Women”. Even though the concept of purity of blood is arguably not deployed for the first time in European history through the invention of the English Thoroughbred, Weil comments on the predominance of this new breed of horse in nineteenth-century French equestrianism and culture at large. It came to “constitute an essential currency within the increasing traffic in horses during the century,” and “the animal equivalent of Gayle Rubin’s ‘sex/gender system,’ those arrangements by which society transforms biological sexuality into products of human activity” (14). The Thoroughbred (pur-sang in French, or “pure blood”), the obsession with which was an expression of nineteenth-century French Anglomania, became not only “the epitome of beauty and nobility” in reference to horses, but also to human beings to denote “a born lawyer or businessman or […] a woman of good breeding” (16). As such the horse as “race/breed” drove the century’s obsession with eugenics and degeneration. Weil then explains that the essays that make up the chapters of the book analyse the fact that “in life or in literature and art, the horse was ‘the animal’ most familiar to nineteenth-century thought” and that it “inspired fundamental changes in human–animal relations” (17).

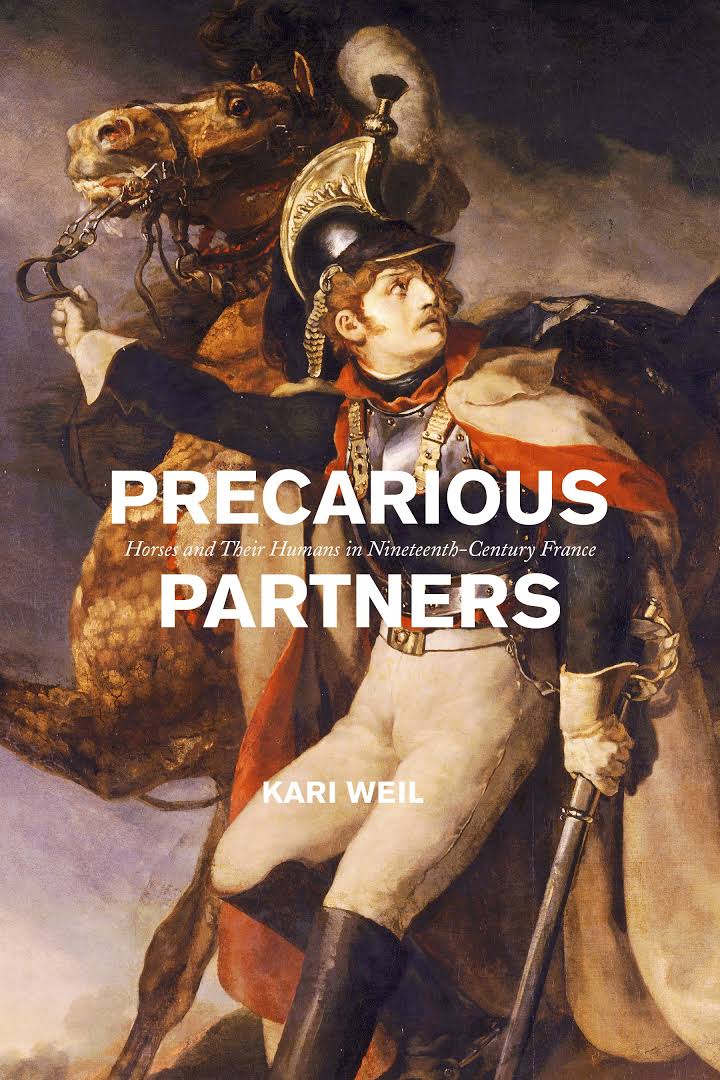

Chapter one, “Heads or Tails: Painting History with a Horse”, is an essay on the role of horses in French painting, and the transformation of that role over the course of the nineteenth century. Weil argues that this transformation worked toward acknowledging horses as partners, and “hence agency becomes especially visible in horse paintings […], which also constitutes a significant challenge to any lingering acceptance of the Cartesian idea of the animal machine” (22). Centre stage in this chapter is occupied by Théodore Géricault because this artist’s painting “defies human separation from nature as it confuses hierarchies of human and horse as conqueror and conquered” (24). Géricault, an artist who was “deeply intimate with horses” and “also rode with what has been called a ‘suicidal passion’” (26), created an œuvre in which horses are “what could be called a queer other who challenges both anthropocentric and gender norms” (25). In Weil’s reading, this queer subversion of the human / animal separation produces in Géricault’s painting Head of a White Horse (1815) an “alert but melancholic look [that] lingers and beckons me. This is the face described by Emmanuel Levinas” (33). The chapter ends in yet another provocative resituating of queerness, this time in reference to the painter’s obsession with equine rear ends, on which he himself seems to pun through a provocative book cover “invit[ing] the viewer to part the slightly opened canvas and enter through the rear” which resembles the rump of a horse (43).

Chapter two, “Putting the Horse Before Descartes: Sensibility and the War on Pity”, analyses the shift in public consciousness, beginning in the late eighteenth century, away from Descartes’s condemnation of entertaining any sort of empathy for animals, who in his view are unfeeling machines and therefore cannot suffer. This shift ultimately gave rise to the first animal protection legislation in France during the nineteenth century. While animal protection may have been “less a response to animal suffering than a means to condemn the abusive behavior of those who worked with animals” (45), under the concept of “pity” human empathy began to be “regarded as humanity’s most honored sentiment” (47). However, this valorization of sentiment was later consciously combatted. “[T]he violent, emotional extremes of the Terror would lead to a retreat from sentimentalism and the demise of an emotionally informed politics” (49), reestablishing Cartesian rationality, which prominently affected public policy around animals. In Weil’s analysis, “our relations […] with horses in particular provided a testing ground for determining what role, if any, pity should play in public life” (50). In this context, the “excesses” of pity are predictably gendered so that it is “woman, who tends to show an overabundance of pity toward animals, often at the expense of attention to other humans (such as her own family)” (52). In a different register, and by way of reference to the poet Charles Baudelaire’s paradigm-shifting critique of pity not as the opposite of rationality, but as a type of feint of emotion, Weil ends the chapter with a discussion of translation, which, as Derrida once noted, is both necessary and impossible: “Translation, in the form of reading and thinking the mute eloquence of those animals that we cohabit with, is our impossible obligation, a necessary step toward rendering our freedom, and our pity, just” (62).

Chapter three, “Making Housework Visible: Domestication and Labor from Buffon to Bonheur”, returns to the history of painting, and centres its discussion on the prominent animal painter Rosa Bonheur. I discuss Weil’s analysis of Bonheur’s painting in greater detail below, so I shall refrain from any further commentary on Chapter Three in this summary. Likewise as regards the fourth chapter, “Let Them Eat Horse”, which treats systematic government policies to habituate the French population, especially the working classes, to consume horse meat.

Chapter five, “Pure Breeds and Amazons: Race, Gender, and Species from the Second Empire to the Third Republic”, is a discussion of the architectural mid-century modernization of Paris (also known as “Hausmannization”) which opened up large sections of the city for the middle classes to display themselves and their latest fashions. Horses came to play a central role in these displays as the formerly aristocratic equestrianism transformed itself into a bourgeois sport, particularly in the ways in which horses allowed women to remake their gender performativity. The role of the amazon, or écuyère, became a way for women not only to transcend class barriers, but to display ambiguous forms of sexuality. “Unlike […] the harlot, the amazon’s enjoyment depended not on a man, but on a horse” (105). In the popular memoires of Céleste Mogador, horses even rescued women from a “melancholy future as wife and mother” (108). Weil briefly mentions the work of feminist scholars like Donna Haraway, Marjorie Garber, and Alice Kuzniar on “dog love” to suggest that she, Weil, may be engaging here in the reconstruction of a history of women’s horse love. Through the analysis of several cartoons and popular magazines, the author acquaints us with prominent popular female figures, especially the Jewish circus écuyère Adah Isaacs Menken. This rich chapter, which in itself contains enough material for an entire book, is really the blueprint for a reinterpretation of women and race in modernity, negotiating the double helix of progress and degeneracy, but unlike the work of Elisabeth Bronfen, for example, where this reading focuses on the relationship of femininity and death, Weil discusses the role horses played in refashioning femininity.

Chapter six, “‘The Man on Horseback’: From Military Might to Circus Sports”, also focuses on gender politics, but here concentrates on the remaking of masculinity in nineteenth-century France as seen through the changing relationship between men and horses. While the previous chapter concerned itself with the ways that women appropriated horses as a vehicle for refashioning femininity, here Weil analyses “how men sought to take back the virility of the horseman and of the horse […] by reclaiming the equine’s physical and sexual potency for themselves” (132–33). These negotiations intersect with social class-based negotiations. While aristocratic men had used horses to display their will, courage and virility for centuries, the display of virility itself became problematic for bourgeois men because it “was a sign that one was not noble and was merely imitating nobility” (135). Weil does not wade deeply into the Foucauldian discovery that the latter part of the nineteenth century was the birth moment of modern homosexuality, but she nevertheless alludes to the fact that these negotiations around visual displays of masculinity, and even the paranoid dynamics around imitation, invoke what Eve Sedgwick would have called homosexual panic: the display of virility on horseback became tainted “with the feminizing effects of spectacle and the homoerotic possibilities of being a male object of the male gaze” (136). The chapter ends with a section on the new sports and hygiene movements. The discussion focuses on popular scientists’ attempts to reframe horseback riding as invigorating sport as well as model training, especially for “inferior beings […] whether they be animals, women, or people of color” (148). Weil does not fail to point toward the eugenics-inflected “anti-degeneration” discourses of the late nineteenth century: “‘If we want to obtain a race of thoroughbred humans, we must use the procedure undertaken to obtain a thoroughbred horse. Let us first create strong and robust individuals who will be, if current prudishness will pardon the term — the stallions of the future’” (149).

Chapter seven, “Animal Magnetism, Affective Influence, and Moral Dressage”, steers the ending of the book in a new and different direction. Taking off from the Freudian metaphor of the unconscious mind as a “Trojan horse”, Weil affirms that in nineteenth-century psychological discourse “psychologists and writers often turned to horses to test or illustrate aspects of subjectivity that could escape conscience or consciousness […] to warn of those beastly forces, shared by horses and humans alike” (156). With the growing interest in hypnosis toward the end of the century, horses and animal magnetism are discussed as models for understanding affective influence, and particularly for influencing “the masses in the service of the state” (159). Whilst there is, once again, a lot of terrain covered in the course of this chapter, Weil ends with a discussion of the philosopher of language Stanley Cavell and the poet and dog and horse trainer Vicki Hearne, both of whom theorize the question of training not so much as a unilateral flow of influence and hypnotism as in Gustave LeBon’s fantasy of “educating the masses” following the model of horse training as a kind of programming of the mind, but rather as a mutual language game. Training, in this sense, is not (ab)using the sensibility, suggestibility, or “capacity of psychological attunement” (172) that characterize horses, but rather “a means of developing a language that both parties can speak and so learn to say something new” (173). And furthermore, “training is a means of entering a relationship and developing a language shared by horse and rider […] with which each can be said to speak, not merely to react” (173). Perhaps most sharply, “[s]usceptibility, the capacity to be affected […] is not the same as subjugation,” and training is therefore always “mutual training” (174–75).

Finally, Weil’s “Afterword” closes with a profound and moving reflection on the “horse as witness” (176). Horses, who have now largely disappeared from human life, “have a point of view […], one we would do well to consider” (177). Weil wonders what the eye of the horse as witness “might be seeing that we miss” (177).

I will now turn to a number of arguments from several different chapters that struck me as particularly interesting. The chapter titled “Let Them Eat Horse” especially shook me, with its repulsive and terrifying detail about slaughter practices. As Weil points out, “the first real efforts to legalize hippophagy took place in 1856” (86). By 1910, “France had become the ‘horseflesh center of the Western world’” (84). Equally appalling is the numbing betrayal exemplified by how quickly and seamlessly horses will pass from a cherished intimate partner to a brutalized bleeding carcass in the great urban metropolis of Paris where close corporeal relationships with horses had become commonplace for the middle classes. Add to that that the nineteenth century is the era of rationalism, science, and the grand biopolitical management of life as resource, and that it saw as well the incipient emancipation of the alienated urban working classes. Within this cauldron emerges the utilitarian discourse of horse slaughter as the means of making use of horses’ bodies, even after their labour had been exploited to the point of breakdown, in order to feed the malnourished workers and thereby improve their productive capacity. Horse slaughter was thus portrayed as both useful and humane.

In other ways, horse slaughter was meant to put a rationalist end to the growing animal sympathy movements. As the second chapter demonstrates, the nineteenth century saw the beginnings of animal protection legislation. Yet the return of Cartesian rationalism to mainstream politics combated emotional political investments. Furthermore, Weil explains that even “socialists of the time, including Karl Marx, feared that a growing animal protection movement would reduce sympathy for the working class — those for whom horses were their livelihood — if not shore up the moral superiority of the middle class and their love of pets” (55). This attitude continues to have resonances today where struggles for animal protection are still often countered with the sentiment that existing resources, be they material or emotional, must be reserved for, or at least prioritize, humans experiencing systemic exploitation and injustice.

Weil elaborates these themes in a slightly different key in the final chapter, where she explores how horses’ sensitivity and susceptibility — ultimately what makes them exploitable to human greed and abuse, or trainable as our “precarious partners” — was resisted in rationalist nineteenth-century France because it undermined the Enlightenment subject: “It was a refusal to acknowledge our human animality, our susceptibility to be affected by others — human and animal — in ways we cannot always know or control” (175). How we understand influence, will, and sympathy are shown to be “a function of many partnerships between humans and horses”, some of which Weil explores in this volume (175). The profound equine (and human) susceptibility, the “capacity to be affected”, and the difficult but necessary task of distinguishing it from falling prey to subjugation, is one of the book’s central themes (174). Weil’s interest lies with historical evidence where, their “susceptibility” notwithstanding, horses are seen as agential partners to humans, not as hapless victims of domestication.

In Rosa Bonheur’s horse-themed paintings, for instance, Weil seems to have found a paragon of this type of ambivalent and rich entanglement with horses, a belated ally in her critique of Francione’s abolitionism. Where Thinking Animals points out the “shameful” lack of imagination in abolitionism’s insistence on freedom as an empty “untethered-ness” that can only be found in death (the death of animals, to be sure), Bonheur’s paintings make palpable the rich potential of artistic as well as quotidian collaborations between horses and people: “Bonheur is the Saint-Simonienne on horseback who partners with her mounts to ‘rehabilitate the flesh’ (human and animal) and turn both toward the collaborative task at hand” (80).

Bonheur was born in 1822 and died in 1899. She was best known as an animalière (a painter of animals) and reached visibility as a painter and sculptor from the late 1840s forward. She is probably among the most recognized female painters in nineteenth-century France. In Weil’s text, we learn that Bonheur challenged social norms not only with her crossdressing lesbianism, but also in her questioning of animals’ lack of agency in human society. Her portrait of The Godolphin Arabian, the legendary English Thoroughbred foundation stallion, depicts the horse in an exuberant fight with another stallion over the mare Roxana. The painting tells the heroic, as well as hackneyed, story of heterosexual romance that finally results in reproduction, and more specifically in the foundation of the English Thoroughbred, and therefore in human fame and profit. One can easily imagine what an abolitionist reading of this painting and its mythology would be. Weil suggests that “what makes this significant for Bonheur, however, is that the agency and the labor behind the making of the breed are animal” (65). In a manner akin to Donna Haraway, who suggests we reconsider domestic human–animal relations along labour-focused Marxist lines,2 Weil also emphasizes that Bonheur “seeks to make this work visible not only in animal resistance but also in the very capacity for cooperation and partnership” (66). In a return to her earlier critique of Singer’s model of animal liberation, Weil finds in Bonheur precisely the instantiation of domestic human–animal relations as a partnership bitterly repudiated by abolitionists: “[I]t was not just animal ‘freedom’ or wild nature as unencumbered by social constraints that was relevant for Bonheur, but animal freedom as necessarily structured and restrained by relations with other animals and humans. Rather than animal liberation, Bonheur envisioned a kind of interspecies collaboration in which the freedoms of disparate partners may not be equal, but nevertheless inspire the curiosity, reciprocity, and affection that many theorists today consider to be our obligation” (67).

Domestication, then, ceases to be a synonym of enslavement, but an ambivalent marker of potential, agency, and interspecies collaboration. I believe that this argument, however tricky and vulnerable to purist notions of liberation it may be, is particularly relevant at this historical moment where the abuse of horses in exploitative sports contexts is once again in the spotlight. From the numerous, and dramatic, deaths of horses on the racetrack, to the ongoing scandals surrounding dressage competition over the spectacularization and subjugation of dressage horses on the international scene all the way to the Olympics, animal liberationists are demanding the shutdown of all public sports activities involving horses, and ultimately even the end of all riding. The abuse is real, no doubt, and the disciplines are in dire need of oversight, regulation, and reform. This indisputable crisis notwithstanding, Weil’s scholarship shows us the histories and complexities of human–equine partnerships, proving that there is value in continued collaborations between humans and horses.

It is curious how much Weil’s description of Bonheur as a rider, writer, and painter resembles the dramatic innovations of horsemanship by the nineteenth-century master horseman François Baucher, whose name is most strongly associated with the equestrian concepts of lightness and voluntary collaboration. In Baucher’s system, the horse is asked and allowed, not coerced, to execute a movement. His or her intelligence, understanding, and collaboration are presumed and cultivated. The rider’s physical influence on the horse is to be minimized right from the beginning of training. Baucher was specifically known for developing a method to work with the horse’s natural balance and improve it for the task of carrying a rider, rather than to impose the artificial balance of the ancienne école of Versailles.

Weil suggests that Bonheur’s painting of horses at liberty produces a “transfer of her own restraint and compulsion to her horses.” In her paintings, the free horses (without rider) produce “movements that are usually induced by a rider, and that these horses achieve them on their own is indicative not only of Bonheur’s controlled brush but also of the horses’ self-determination. This combination of freedom and training is what Bonheur sought” (80). Some of the resonances between Weil’s characterization of Bonheur’s paintings and Baucher’s method are striking, particularly the conjunction of freedom and training. Baucher’s influence on French and international horsemanship in the nineteenth century cannot be overstated. With his aesthetic and relational principles, developed in the manège and his prolific written œuvre, and exhibited in countless public performances, Baucher paved the way toward modern dressage. This is true also in the sense that it was some of his pupils and pupils’ pupils, most notably General Albert-Eugène-Edouard Decarpentry, who in the 1950s wrote the dressage rules for the Fédération Equestre Internationale, the governing body of international equestrian competition.

If, then, there is one question I would bring to Weil’s text, it is about the nearly complete absence of Baucher’s figure in a book that covers a lot of terrain as far as the role of horses within nineteenth-century French culture, and the enormous transformations that this culture underwent. From an equestrian perspective, Baucher reformulated the classical Versailles school of French horsemanship, which formed the commonly agreed upon basis of all dressage training, and adapted it to modern riding, updated the rider’s relationship with his mount centering it in lightness and collaboration, and produced these changes in the context of French “anglomania” on which Weil has otherwise much to say. Baucher and his pupils no longer rode the classical horses of Iberian lines that defined the Versailles school. Instead, they adopted the modern English Thoroughbred, which had been bred with a very different balance and different purposes in mind, most notably “open forward riding.”3 Given the centrality of Baucher in these developments, as well as his relative absence in English-language equestrian discourse and therefore his need of a new cultural ambassador, his equal near omission in Weil’s text is baffling.4 I believe Weil’s rich and passionate explorations of Bonheur’s art would have benefitted from being put in conversation with Baucher. He was the quintessential nineteenth-century French equestrian artist. His innovative training method was based on recognizing and engaging the intelligence and agency of horses, an attitude that Weil identifies in Bonheur’s paintings. Had she woven her discussion of Bonheur into the rich fabric of Baucher’s legacy, Weil could have augmented her analysis of equine agency in French culture by considering the importance that Baucher holds today in horse training when understood as artistic dialogue with horses.5 Unlike in the dominant conception of dressage as an equine sport where the horse serves as a tool or instrument akin to a bicycle or a motor vehicle, mechanistically executing what the rider instructs him or her to do, in artistic (also sometimes called “academic”) dressage, horse and rider are dance partners choreographing performances together in an improvised manner. What matters in this distinction is what Weil already found to be true about Bonheur’s paintings: that horses appear as active, intelligent agents. As the renowned twentieth-century Baucherist René Bacharach put it, in artistic dressage “la matière grise devrait jouer un rôle plus important que la quincaillerie” [grey matter should play a more important role than hardware].6 Equitation, in other words, is a meeting of minds rather than mind (human) over matter (horse). This, once again, resonates with the ending statements in Weil’s last chapter on training as a way of developing a common language between rider and horse.

Notes

-

Kari Weil. Thinking Animals: Why Animal Studies Now? (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 136.

-

“The Marx in my soul keeps making me return to the category of labor, including examining the actual practices of extraction of value from workers. My suspicion is that we might nurture responsibility with and for other animals better by plumbing the category of labor more than the category of rights.” Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 73.

-

See Donna Landry, Noble Brutes: How Eastern Bloodstock Transformed English Culture (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 2009).

-

The most extensive of Weil’s scarce references to Baucher comments on his gender politics: that women should “ride only calm and well-trained horses.” Although mentioning that he was a “celebrated riding master and advocate of haute école dressage”, she never explores the content of his fame (8).

-

As Galadriel Julie Sparrow — the moderator of the sometimes turbulent, France-based Facebook group François Baucher, which has more than 7,600 members — put it in a presentation at a Colloquium commemorating the 150th anniversary of Baucher’s death, on 14 March 2023 at the Garde Républicaine in Paris: “Le Bauchérisme c’est quand l’équitation devient Art” [Baucherism happens when equitation becomes Art].

-

René Bacharach, Réponses équestres (Lausanne: P.-M. Favre, 1987), 64.