Older Humans and Their Dogs

Interspecies Companionship and Anticipating Loss

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.15998

Keywords: human; dog; companionship; interspecies; ageing; loneliness

Abstract

Loneliness and a lack of socialization can have a deteriorating effect on life experience and health. Unfortunately, loneliness is an experience often felt by older people, and interspecies companionship can provide valuable and daily interaction that is positive for well-being. In the place of another human, a dog may inhabit a role as a provider of emotional support.

In Judith Butler’s sense of performative identity, there is a becoming of that which we do. Using an approach of working with (rather than on) people, this informs sensitive and sympathetic methodologies for an analysis of the significance and benefit of interspecies companionship for older people in the initial stages of my artistic research project, Dogs and the Elderly. Made with participants of the Alzheimer’s Society’s “Memory Cafés” in Nottingham and Lincolnshire (UK), the project demonstrates how interspecies companionship can be valuable for supporting the emotional health and well-being of older people. This illustrated photo and text article discusses how the project’s older humans and their dogs inhabit a togetherness within supportive interspecies relationships in various ways, and how this contributes to their lived experience. It explores the stories of a group of people, living with or supporting others with early-stage Alzheimer’s, who speak to companionship with their dogs to articulate the significance of the relationship from their perspective.

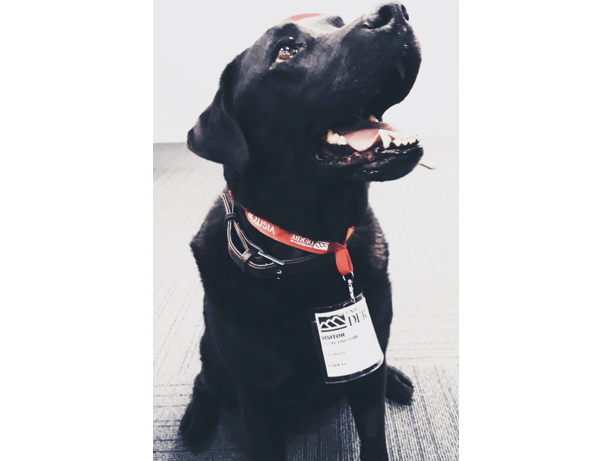

During the spring of 2014 I met Oscar, a large black Labrador. The meeting was arranged through the UK’s “Borrow My Doggy” scheme, an initiative that pairs up humans with other people’s dogs when they cannot permanently accommodate one of their own. My German Shepherd dog, Woofer, had recently died and I felt a sense of loss and emptiness where a canine friend should have been. Oscar was the first dog I met on the scheme and, as we got on so well, he was also the last. He was gentle and likeable, displaying a kind and approachable manner, and we quickly established a friendship spanning nearly ten years. His amiable nature to all humans allowed our friendship to develop creatively into a research project involving older people. Specifically, Oscar became an invaluable collaborator in my artistic research project, Dogs and the Elderly.

With the increased vulnerability that often accompanies advancing age, social isolation and loneliness can present a very real threat to health and longevity.1 Loneliness, for Anne Forbes, “may be described as an unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship.”2 Kimberley Smith regards it as “a phenomenon that has social roots, but a psychological presentation.”3 Loneliness can come to represent the “psychological embodiment of social isolation”.4 Cheryl A. Krause-Parello describes loneliness as a “painful and unpleasant stressor”.5 Older people, for a variety of reasons (including mobility, health, lack of family or close friends nearby, financial and other kinds of insecurity, and personal fears for safety) are “particularly susceptible to a blitz of relational losses”, putting them at increased risk of loneliness.6 Contributing factors include “major life events and transitions, such as developing a health issue, retirement or bereavement”, which may increase the risk of experiencing loneliness.7 Prevention can be found in positive social relationships as they are among “the most important things we need in life; they are crucial to our wellbeing and our physical and mental health.”8 But how do the people experiencing this actually feel, and can living with a dog help to ameliorate this condition?

Dogs and the Elderly is an artistic research project that proposes to discover what the effects of living with a dog can be in this respect. Through extending invitations to a small group of older humans, it aims to capture first-hand stories that speak to the personal and often complex feelings about individual lives lived with dogs. Concerning the significance of interspecies interactions for an older person’s wellbeing, the project seeks to practically discover how life with a dog can give added value and purpose in life. The project offers an opportunity for its participants to speak and to have priority given to the sharing of their stories, through a methodological framework built on listening and inclusivity.9 In foregrounding personal attestations on individual reliance and need in this way, the project is itself significant.

Methodologically, Dogs and the Elderly engages artistic research, as an un-prescriptive, sensitive, and interpretative approach to knowledge production, which, I suggest, enables sensitive interactions and encounters.10 Offering an opportunity for people to speak of their intimacies and connections with dogs through this method enables others to listen through creative translation. This situates the creative act as “a process of correspondence”.11 Responding sympathetically to the person directly respects the individual and their right to contribute through responsive engagement.12 As an example, the project was named together with its volunteers from the Alzheimer’s Society’s Memory Cafés, based in Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire.13 Through this act of naming of the project it attempts, informally and with sensitivity, to explore the material and affective conditions that help an older person managing a degenerative cognitive disease engage in a binding and intimate relationship with a companion dog.14 Contributions came from attendees of the Memory Cafés, including those who were experiencing the condition themselves, or were performing a caring role for a partner with early-stage Alzheimer’s.15

As my research companion, Oscar was active in the initial phases of the project, demonstrating the pleasure and positive effect of being in the company of a dog through direct engagement. His presence at the Memory Cafés gave a welcome experience of human-canine togetherness for those who wished to indulge in his company. Harold Herzog states there is evidence to show those who enjoy being with nonhuman animals experience “more positive moods, more ambition, greater life satisfaction, and lower levels of loneliness.”16 Oscar’s value was evident through the positive responses expressed towards him, demonstrating the mood enhancing effects of being with a dog. His difference and familiarity within the Cafés suggest why this is possible — dogs provide interactions and companionship in ways that other humans cannot. Through Donna Haraway, we understand companionship as the connection established between mutually reflexive co-living bodies.17 Companionship is enabled through co-existence, and the practicalities and familiarities of daily interspecies living. It suggests an equitable relationship that transcends the binary of nonhuman animal pet and human owner.18 Companionship, for Haraway, is a form of becoming-with enabled through an intuitive acceptance, and responsiveness to the other.

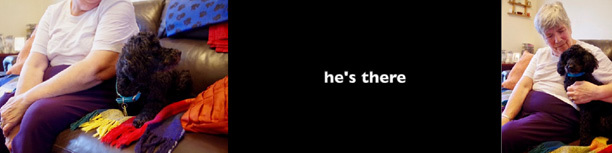

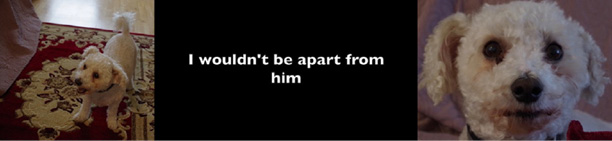

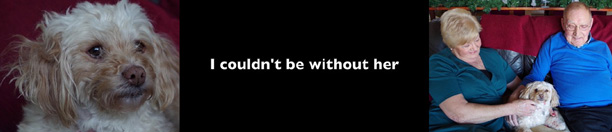

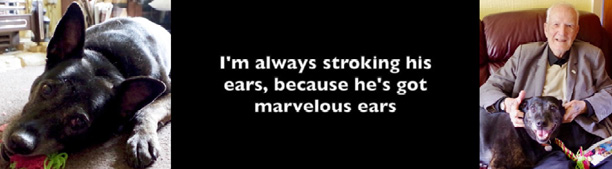

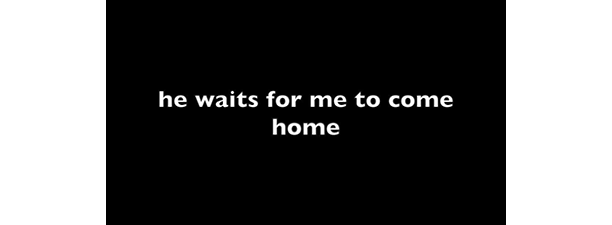

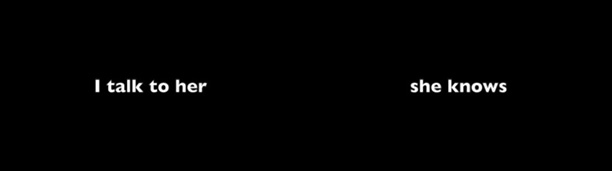

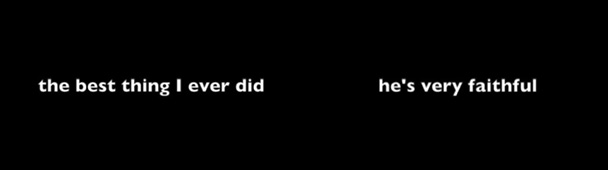

In the images interspersed throughout this essay, the words that appear as quotes act as a critical companion to the photographic images, as a representation of the shared lives of human and canine bodies charted across the project.19 The quotes, placed as images throughout the text, are taken directly from the individual storytelling encounters.20 They provide snippets of the dialogue given freely in the people’s homes with their dogs by their side. Because of the types of stories gathered, and through the intimate nature of their details, the initial story’s themselves are where the project establishes the greatest personal connection and impact. The stories offer reflections on individual, but generally considered anticipations of loss, where all participants spoke of their fear of losing what they presumed would be their last dog. With the passing of time since the stories were shared a few years ago, this is a loss which has presumably now occurred.

Oscar

The Benefits

To live with a dog is to be open to the experience of another habitually and with regularity. For many, relationships with dogs are “a central element of human life.”21 Primarily, this is due to their capacity to exist side-by-side with humans, which is possible because they “exhibit many of the same cognitive flexibilities and biases that characterize our own species.”22 A product of this cognitive similarity is their ability for synchronicity and emotional contagion that leads to acts of empathy and attachment with others. “Emotional contagion, a basic building block of empathy, occurs when a subject shares the same affective state of another”, which is an outcome of cohabitation.23 Beyond acts of labour for humans, and as its oldest domesticated companion animal, dogs can become effective providers of support and associative reassurance. Kendra Coulter refers to such support and reassurance as “voluntary” work, suggesting that it concerns the provision of “joy, kindness, and comfort”.24 Dogs’ capacity to provide companionship is of value to humans who, as inherently social beings, often seek comfort from others, and this is “especially important for seniors, vulnerable or marginalized people.”25

As part of a working scenario and companionable dynamic, dogs have historically proven to be good company for humans, which, for Caroline Knapp, “strike[s] deep chords in us […] bolstered by […] individual experiences.”26 Margret Grebowicz suggests that a “dog’s willingness to work is a product of [their] interaction with humans.”27 Additionally, dogs have the capacity to respond to their human companion’s needs, and this serves as a reminder of how they “provide primary connections across animal and human worlds.”28 In the case of service dogs, a dog can “literally [be] experienced as an extension of the blind owner’s self, a complex and unique perception that also hinges on an understanding of shared human and canine identity.”29 These attachments allow dogs to adapt to the individual person with whom they live.

The animal behaviourists Charlotte Duranton and Florence Gaunet also describe this adaptive capacity of dogs in relation to their “sensitivity to others’ behaviours and the ability to adjust their own behaviour accordingly.”30 Dogs’ capacity for synchronicity enables their responsiveness towards others. Through the synchronicity within companionship, they benefit humans by providing “life-sustaining emotional support and motivation”, that is life-affirming and transformative.31 Health-based research by Krause-Parello suggests that “companion animals may have a significant effect on the reduction of loneliness and the promotion of health.”32 As the “attachment between humans and their pets, provide(s) a unique and accessible source of support”, this is a good outcome for the human.33 The domestic human-animal relationship, therefore, can positively impact mental health, as it supports the individual in deflecting any of the potentially negative and debilitating effects of loneliness.

Companion animals bring increased value not only for older people but also those living alone, experiencing homelessness, and those isolated from regular contact with others, as the relationship provides a sense of regularity, routine, and co-living. Indeed, “most pet owners believe that their companion animals are good for them.”34 Essentially, this is due to their providing and maintaining a supportive framework of contact that is beneficial. For the project’s demographic of older people with early-stage Alzheimer’s and partners who care for those in this position, this contact can be particularly useful. In relation to the expansion of the application of corresponding care, such contact allows additional measures to be occupied by other species. The human–animal attachment becomes a supportive mechanism in this respect, that enables the human to live positively through the experience of being with their domestic companion.

As noted above, a companion, for Haraway, is an extension of the relationship between human and nonhuman animals, but one where equality is necessary — a situation where there have “to be at least two to make one.”35 The history of human and dog companionship speaks to the reflexivity of giving between the species and says as much about the needs of both within their relational duality. In return for companionship in a positive relationship, dogs receive benefits, such as protection, warmth, food, and shelter.36 A dog in this context is more than merely a pet for older people who may rely on their daily canine interactions as life enhancing and fulfilling. Companionship is more than a human–nonhuman animal relationship; more equal, and responsive to need and circumstance. This greater sense of equality is possible due to the levelling of hierarchies and positions within the binary of them and us, to forge a mutually beneficial relationship. At its most equal, this is structurally flexible and mutable in response to individual input and need.

Caring daily for another creature provides intellectual and cognitive stimulus through the provision of a sense of purpose and use. The care the human gives to their canine, such as feeding, exercising, and managing health issues, can make a difference in how useful the individual feels. Feeling useful and of use to another can mean the difference between falling into declining health or not. The Dogs and the Elderly project acknowledges and asserts, in line with a suggestion by Coulter, that embodied human–canine interactions facilitate reciprocal sympathetic care and care-giving. Through this, Coulter argues, we should, “recognize that the ‘social’ is multispecies”, and that dogs can care as much for humans as humans can for dogs.37 Physically or psychologically, through a “being with” as companions, embodiment, as affirmation of the experience with the relationship, creates interspecies cooperation and care.

Using the Right Method

In Judith Butler’s sense of performative identity, there is a becoming of that which we do.38 Taking Butler’s position as the affirmative and positive, Dogs and the Elderly worked with, rather than on people and their dogs. Knowledge is a practice that constitutes a learning through doing, and a thinking through process, and this research demonstrates how this operates in application.39 The notion of thinking through doing with others together is paramount.

Due to their receptiveness to humans and engaged levels of synchronicity to others, there is much to learn from dogs. Thus, the methodology of the project looked to the dog’s capacity for responsiveness and synchronicity with others to establish sensitive interaction and to allow their immersion in the process. Practically, this informs how the research enacts fair, respectful, and responsive attention to human accessibility to contribution. Structurally, and in practice, the project was engaged most actively with this methodology at the time of its making through the story-gathering exercises.

Experiencing the early demands of Alzheimer’s, or supporting a partner who is, can mean that the presence of a dog in the home becomes increasingly important. Sympathetically and sensitively gathering stories from such a group requires an informal application of performativity, where the activity enables a feeling of relaxation and a sense of interactive and participatory ease. Henk Borgdorff states that artistic research concerns “performative [art] practices, in the sense that artworks and creative processes do something to us, set us in motion, alter our understanding and view of the world.”40 Although not wholly relating to speech acts in J. L. Austin’s sense, in this instance performativity relates to the multiplicities within the exchange and its method of artistic research. Performitivity positions (canine) cause and (positive, companionable) effect in this context, and how it informs the sensitively constructed framework for gathering the stories first-hand. Additionally, this approach relates to Peggy Phelan’s and Judith Butler’s use of performativity that extends to the and an other body engaged in repetition and ritual acts of embodiment. The bodies in this context are animal and dog, as that which is different, but companion to the human. Additionally, the performative structure includes the wilful construction of an environment to promote, and not restrain the sharing of stories. This is managed through careful attention to the space and pace, as well as the comfortable and sensitive manner of the exchange.41

Opportunities for human–canine companionship become even more important when opportunities for socializing with humans become less frequent, which the story-sharing sessions explore and document. Not only were the sessions centred around the individual bonded relationships of human and dog, but they also provided a situation for performative interaction whereby the human volunteer had priority in the engagement. The term “bonded” can be loaded within the context of interspecies companionship. The project acknowledges that any physical bonding device, such as the companion’s walking leash, connects, but with one in control and the other the controlled. The leash is also, however, a visualization of the invisible bond between human and canine in their mutual pursuit of an urban or rural walk, an act that seeks harmony through an equitable pursuit, even though it is usually set around an imbalanced dynamic.42 For one speaker in this project, the leash and the daily walk with their dog is a priority within their story, and it is therefore of note.

An Invitation to Share

The relationship between Oscar and me transcends traditional domestic cohabitation arrangements. This operates without the foundations and measures of who provides the other with what, in a practical caring and homely sense, and beyond the confines of fundamentally privileging domesticity. Even in respect of the equality noted in Haraway’s conception of companionship, there is often an imbalance in the domestic (however slight); the human, essentially and normally, tends to make the decisions about the daily routine. In my relationship with Oscar, companionship seems truly possible because we do not cohabitate. Our companionship simply does not operate within the same co-living structures that define interspecies domesticity. Grebowicz states that “within life with dogs […] the distinction between self and world pretty much disappears”, and this is typical of the reciprocity in our friendship, which sees enjoyment in the experience of togetherness with mutual engagement and equal reward.43 The self, for Grebowicz, relates to both the human and dog, each of us alike in this context, and this extends into our introduction to the meetings and the people in attendance.

On attending the meetings of the Alzheimer’s Society’s Memory Cafés, Oscar and I encountered a variety of people with different levels of concentration and interest as to why we were there. We went to three meetings a week in various suburban locations in Nottingham, and one in an economically oppressed and rundown seaside town on the east coast of England called Skegness. One meeting in Nottingham had over fifty members present and appeared somewhat riotous and uncontrolled; another had eight people seeking entertainment and stimulation; the other slotted us into a packed schedule of quizzes about historic British transport vehicles and different types of World food to a membership of twenty. We met with fifteen people in Skegness in the context of a discussion of the local seafront and promenade.

The opportunities to meet new people presented exciting days out for Oscar. He displayed the same familiar signs of eagerness and happiness as when we would go on our regular woodland unleashed walks, but with increased alertness as he came to understand that we were going somewhere new in the car. Not least the act of putting on his special and best collar signalled we were doing something different before we embarked on the journey. On arrival at the meetings Oscar was, by agreement with all present, let off his lead to wander the room. Indeed, many encouraged this before the question was asked. There was an active migration of attention to his presence upon his unleashing, due to the unfamiliarity of his species in these (human) meetings. Interest grew in this unusual visitor once he could gently greet and meet the people at the Cafés. He had his ears tickled, his belly rubbed, and his head massaged, in return. His positive reception demonstrates how important interspecies contact is to so many; this unusual interaction differentiates the Café meetings from others.

During his adventures and discovery of new people, I spoke to the groups to explain why we were there and what my request involved. Some listened, some did not — some were more engaged with the friendly canine wandering amongst them than the human standing nearby. As Oscar provided a different experience at the meetings, this is understandable. Eyes looked down as hands gently caressed his head. He travelled from person to person. As individual Café users fussed, scratched, and stroked Oscar, a few initiated conversations with me. Through this I responded to additional questions to explain why we were there and gently asked:

Do you have, or have had a dog you would like to talk about?

Would you like to share your story?

During these encounters, many questions of Oscar can be heard:

“What a lovely dog, is he coming again?”

“Does he need a bowl of water? Maggie, can you look after the dog please?”

“Does he like his tummy rubbed?”

During each of the Memory Cafés and through these discussions people express that they want to talk and share their stories. As a result of our attendance, we meet Jean, John and Barbara, Frank and Laura, Reg, and Mandy*, who offer to share their stories.44 We set a date and we meet, often a month or more later, but this time in their home or a site of their choosing. The meeting place is highly significant, as the canine and human will be at their most relaxed within the familiarity of the home or preferred place. Their domestic habitats specifically allow the humans to be at ease through the familiarity and normality it brings to the situation. A significant contact zone where their stories environmentally locate and flourish, it is important to hear their words within their homes wherever possible. As a shared space, the home is also an environment that facilitates the interspecies companionships on which they rely. Specifically for the project, the familiarity of the habitat enhances the capacity for the sharing of stories and their ownership of the activity. Enabling free and unhindered speech, the home environment allows the researcher to be less of an instigator and more of a witness.

Left to right: Frank, Laura, and Lucy; Jean and Dandy; John, Barbara, and Max; Reg and Harvey

Listening

We schedule the dates to meet loosely over a changeable timetable. Occasionally, we reschedule due to an unexpected hospital or doctor’s appointment, because the human or dog is not well, or there is a family issue. Sometimes the volunteers are simply too tired or there is too much happening on that day. When we meet the discussions are informal and conversational allowing life stories and thoughts to emerge. Beyond the general sense of concern and thinking for their current position and their dogs’ futures, there are other relevancies that become apparent. The storytellers speak to intricate and intimate elements of their own lives, framed around the discussions of their dogs’ habits, welfare, and needs. Increasingly, there is a shift from thoughts regarding companionship to the self and their experience of complexities within negotiations of the everyday. Through the progressive ease in the unfolding of reflection and sentiment there is an awareness of the humans warming to the attention they are receiving from someone who is listening with intent and interest. Visibly, and through knowledge, experience, and understanding, I see them become increasingly confident in their manners, gestures, and speech. Initially conscious of the microphone placed nearby, the increasing ease eventually renders the apparatus inconspicuous. After a while they simply stop looking at it on the table in front of them. Overall, there is a sense of them wanting to talk.

The recorded stories offer varying insights into the lives of five human–canine households experiencing and navigating early-stage Alzheimer’s. They speak of their dogs as integral to the family, and how they manage and behave together daily, demonstrating the ritual and performative within the home environment. Jean is a helper in one of the Memory Cafés in Nottingham, and lives alone with her three-legged poodle, Dandy. With Dandy sitting by her side on the sofa, and with her hand gently stroking the length of his back, Jean talks of her emotional dependence on him for routine, purpose, contact, and comfort. She says that he senses her change in emotions and feelings and is there for her in an hour of need. There is physical dependency and attachment that often sees Dandy come toward her to be close, so that she feels the calming weight and heat of his body against hers. When her husband died, Dandy became her reason for living. She explains that “I felt alone, and needed something with me, and he was.” Dandy became her something to rely on, and she holds him affectionately as she talks fondly of their relationship, saying with a smile that he is her abiding and “real comfort.” Occasionally, Jean looks into his eyes and he meets hers in return. Whilst gesturally demonstrating their attachment as she administers gentle strokes to Dandy, she discusses their bond which is, “very much about him and me.” Krause-Parello states, “as loneliness increased for the older woman, there was a significant increase in pet attachment”, which is evident in the situation of Jean and Dandy.45 For his part, Dandy appears content and safe. In fact, so much so that he begins to fall asleep. Although this relies on observational judgement, his manners and behaviour portray a relaxed attachment to Jean. He feels safe to not be on guard and wary of danger in her company within their home.

Jean and Dandy

Max, a small fluffy white dog, plays with a ball as Barbara talks of how she feels safe to leave John, who has early-stage Alzheimer’s, in the house alone if Max is there. Barbara states that her daily cleaning job provides her with respite from their home situation and full-time care for John. This would be impossible without Max, as she would worry about what is happening whilst she is not at home. Max, therefore, is an enabler of relief, for Barbara, from the burden of caring for someone who is ill. He is a trusted chaperone and companion for John when she is absent, and he makes it possible for Barbara to have other experiences beyond the demands of their domestic situation. Occasionally, John gets up from the sofa and goes over to Max to touch his head, as if checking in, before returning to his seat. He is ever watchful of Max, and offers that “he is my reason for living and to keep going on happily.” In subtle contrast to John’s attentiveness to Max, Barbara predominantly meets my eyes as she talks. For her, the attachment differs from John’s as Max provides a means for her to be beyond the house and away from the caring that she needs to administer. As her enabler, their bond is different, less attached, but nevertheless still as significant. Without Max, she acknowledges, her life, its structure, and possibilities would be different.

John, Barbara, and Max

Similarly, Lucy, a small white rescue dog from Greece, is chaperone and companion to Frank, enabling him to leave the house safely without his wife. Frank can go to the shops alone if Lucy is with him, and this provides a sense of daily normality. Laura, Frank’s wife, offers that she trusts Lucy to bring Frank home should he lose his way, saying, “she knows what to do.” She states this has happened on several occasions, but thankfully Frank has learnt to ask Lucy for assistance. He says, “sometimes I forget where I am, and I say, ‘Lucy, take me home,’ and she does.” She responds by taking charge in leading them home and to the safety of their known environment. Lucy provides Frank and Laura with a safety net: for Frank, this means the freedom to leave the house unaccompanied by his wife and to experience a form of regularity and normality; Laura finds assurance in the knowledge that Lucy will return Frank safely and she states this allows her to be at ease. Lucy enables the independence of each. They sit with her between them on the sofa as they talk, stating that Lucy adopted them, and they believe that “she needed them.” “She kept showing up at our holiday apartment,” John says, “so we decided to bring her home, and now we could not be without her. It has changed — we thought she needed us, and it turns out it is the other way around.” They clearly adore her, they say as much, but the affection they feel is also visible and palpable. They stroke her head affectionately and gently, and she looks at them adoringly before falling to sleep. In observing the contentment of the three companions in this situation, this looks to be a scene that is regular and usual.

Frank, Laura, and Lucy

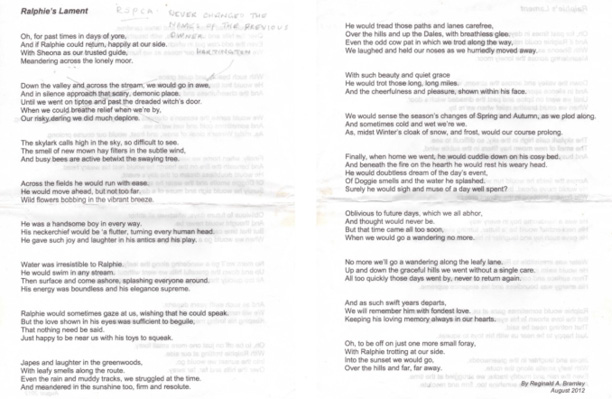

Reg, an ex-military man in his eighties, talks of his life with dogs. He demonstrates pride in the telling of his story, which involves walking weekends away for him and his dog of the time. Of his current dog, Harvey, he says, “we couldn’t be without him.” Reg has had many relationships with dogs, but the “love of his life”, he says, was Ralphie, a Jack Russell Terrier. Trips with Ralphie included long cross-country hikes, sharing sandwiches and biscuits, and sitting by the campfire together at the end of the day. Reg asks if he can read a lament written for Ralphie after his death. As he does this, Harvey is by my feet playing with a toy; his wife stares out of the window seeking distraction from the increasingly emotional lament as it unfolds. Reg reads of Ralphie’s handsomeness, his gazes as if he were wishing to speak, how swimming was a favourite activity, and of their japes and laughter together. When he begins to speak of Ralphie’s death towards the end, Reg’s voice begins audibly to break, and the room becomes tense with the emotional longing and upset he is revisiting.

Writing about being with a companion animal has “the same psychological benefits [and effects] compared to thinking about one’s best friend, suggesting companion animals provide a direct source of social support.”46 The emotional reading of his own text shows how significant its writing was, and still is, for Reg, in relation to the memory of their companionship. His devotion to Ralphie is evident in text and speech; Reg clearly still mourns his passing. All are silent as he concludes reading, not wanting to intrude into this moment of reflection and sadness. As I leave, Reg thanks me for taking the time with them, and quietly hands me a paper copy of the lament. Still bearing pencil notes of Ralphie’s adoption written in his hand, this is a highly personal artefact. The fact that he gives it to me as a gift suggests Reg has found our interaction to be positive, as I do not think he would offer the item if he had experienced it as negative, awkward, or uncomfortable. Presumably, he wanted to make a gift of the poignant artefact within his story to a person who wanted to listen.

Reg and Harvey

“Ralphie’s Lament”, written by Reg in 2012

In Skegness I meet Mandy, who asks to speak with a request that her recently diagnosed husband not be present. Her husband is a local councillor, and his condition is not common knowledge. She states that she really wants the project to include her story, to share with others what is happening to her, but her husband cannot be involved. Mandy is struggling with the emotional, practical, and social demands of serving as his primary carer. She is the only person who does not want to have her photograph taken, stating a fear of others knowing of her husband’s illness and the change it has brought to their lives. To further retain privacy, she requests that we meet at the Skegness Memory Café centre. Because of these factors, and as she wants the focus to be on her story alone, her dog is also not present. As the project gives ownership to its storytellers, Mandy sets the conditions she needs to feel secure, safe, and at ease. These are accommodated responsively and completely. The break in daily regularity, she explains, would raise her husband’s suspicions if she were to leave the house with the dog at the time when she would normally go shopping for food. Regularity and routine for her is binding and performative within the home and the structural day-to-day. Privacy in this matter is vital for Mandy as she is acutely conscious of how her social life will change once others become aware of her husband’s illness. She aims to keep this a secret for as long as possible, saying, “I do not want people to know.”47

When we talk, I ask her if she is comfortable and sure about taking part; she affirms that she wants to speak, and that she needs to “talk to someone outside of Skegness.” Women, particularly, can develop “a dependence on attachment support (with their pet) when stressed”, which is relevant to her act of sharing.48 Mandy’s story demonstrates how interspecies attachment can provide support. She states at the outset that in taking her dog for walks, she has a reason to leave the house unaccompanied. Here, she finds respite in the organized solitude with her walking companion, finding the space to recharge, refresh, and gather herself before returning home. Providing refuge from her reality at home, she states that her dog is a means to escape a situation with which she is struggling to cope. This includes the social context, as she explains that she can interact freely and with normality with those she meets when walking her dog without fear of the exposure of her husband’s illness and their domestic reality.

Even though they walk together as a pair, it is difficult to determine how connected they are in the pursuit. Mandy talks of being within herself during the walks although she is conscious of being in the company of her dog. Alone in her thoughts, but not alone on the walk. She feels and wants her dog’s bodily presence, which she is aware of as he walks leashed beside her. Mandy acknowledges the alignment of the rhythm of their bodies, stating that she senses how they fall into the same gait as they travel paths and canal sidings. However, the physical togetherness within the daily act appears somewhat emotionally fractured, as the dog is primarily her vehicle for escape. Despite her acknowledgement of his presence, she is semi-absent and disconnected, which hinders their relationship’s companionable fulfilment. The daily walking, she concludes, is necessary as a support through the increasingly demanding management and care of her husband’s diagnosis. In this way, her dog provides her with a service of rescue; he provides a means to an end, and a “reason to go out”. As she leaves, I watch her straighten her back as if to steel herself for the return to her normality. Her story is, perhaps, the most complex of them all.

The Connection

In its many forms, contact with a companion animal is valuable to human wellbeing, as the above stories show.49 The interspecies companions in the project enact togethering through daily contact and the sharing of pursuits, which enhances wellbeing and a feeling of effective domestic support. There is a need for contact with the other in various ways within the experience of domestic socialization. This locates with a need to “be” with another, however slight and in whatever construct is necessary. Catherine Amiot, Brock Bastian, and Pim Martens write that “research has demonstrated that relationships with animals are good for human health, because they can reduce stress and medical complaints while also increasing self-confidence.”50 Additionally, companion animals “play a soothing and calming role in the wellbeing of those who suffer from dementia and the families who care for them”, as is evident in this research.51 Mandy, Barbara, and Laura all recognize the care and respite opportunities their dogs provide, and Reg and Jean acknowledge the value in their dogs’ emotional and physical support and companionship. Within the stories this companionship is attentive, relational, and varied, and impacts significantly on the positive human experience. Coulter suggests this impact is possible because “companion animals continuously assess the people with whom they live, physically and emotionally, and […] provide care of various kinds, especially emotional support, through their presence, behaviours, interactions, and touch.”52 In this way, they become regular enablers of their human’s improved wellbeing in whatever way seems necessary.53

Although the individual stories are their own, they feel representative of many. A dog can facilitate escapism, be a companion, provide purpose, and create safety, amongst other things, as spoken to within these exchanges. The stories represent, to draw on Haraway’s work, how “making kin” becomes possible.54 The companionable nuances within speak to a variety of physical, emotional, and psychological human-canine interactions, entanglements, and dependencies. Contact, as relational and interconnected in this context, sees “kinning” made demonstrably visible and understandable during the enactment of storytelling, but also through the details shared. The rhizomatic potentials disallow binaries and refute their conditions, encouraging multiplicities and mutualities through affectionate portrayals of kinship. In our discussions, the storytellers frame their dogs, to quote Grebowicz, as “both agents and subjects of rescue.”55

All animals (including humans) need touch for affirmation of the self, as an individual and within groups. Interspecies companions communicate through multi-sensorial acts of touching, which is essential to level unstable hierarchies and create mutual acts of relational comfort and balance. Jacques Derrida suggests that “without touch animals would be unable to exist.”56 Walter Benjamin suggests the physical gap between individuals closes, even if only for a moment, through acts of positive touch, and this allows emotional and psychological connections to build.57

The chemical calming effects of touching a dog informs how the relationship develops towards relational and mutual acts of embodiment. Studies show that human-animal contact produces oxytocin in both species, a chemical that cognitively informs positive social bonding. Connectivity develops as people “with high oxytocin levels and lower cortisol [stress hormone] when interacting with their dogs tended to have closer bonds” with them.58 The relationship, in effect, feels good, and therefore investment is given to its development and maintenance. “Tactile interaction [specifically] between humans and dogs increases peripheral oxytocin concentrations in both”, which further explains mutually beneficial interspecies attachment formation.59 Positive chemical reactions influence how interspecies bonding is producible through various methods of contact, which is relevant to the relationships and stories within this project. Stroking a dog is an example of a tactile interaction, which is a binding and familiar act of positive intention and connectivity; another is the verbal and spoken, where informality creates an openness and engagement within the parameter of shared communication; it can be as simple as looking into each other’s eyes, as an act that “not only facilitates the understanding of another’s intentions but also the establishment of affiliative relationships with others.”60

Reciprocally, the dogs in the stories receive much in return, which creates harmony and mutuality within the domestic environment. Indeed, “the action of stroking an animal has been found to reduce the animal’s heart rate”, and the calm manner displayed by the dogs seems to confirm this.61 As the stories describe, they forge relationships around the need and wants of each other, to be mutually life affirming and co-supportive in their management and construction of productive togetherness. Contact is therefore significant within the context of interspecies companionship, as it enables and supports its structure to develop to mutual benefit. Contact creates connection, which helps forge companionship that is not only physical, but also emotional and intellectual, and relates to methods of stimulation and connection with another.

On Being with and without

There are moments where details within the stories of Jean, John and Barbara, Frank and Laura, Reg, and Mandy, particularly prick at sentiment regarding their interspecies futures. This concerns, for a variety of considerations, how they may come to be without the companionship of a dog. Within the stories they refer with fondness to dogs loved and lived with in the past, their joys and sadness at their passing, the “what will happen ifs” and the “what has already happened”. Experiences of there-ness and the not there-ness are spoken, together with the lessening presences and increasing absences they imagine they will experience as their dogs die. They talk of the impending void of suddenly not being with their companion, should quality of life decline to the extent that they move to the care sector, a place that cannot accommodate their dog, or if their companion dies before them.

There are “repercussions of ignoring the voices of […] marginalized humans”, as Marti Kheel states, and this is pertinent with respect to the personal hopes and needs of Reg, Barbara, John, Mandy, Jean, Laura, and Frank.62 Each of them refers to the “burden” associated with being forced to leave their dog to a different fate, to a life in shelter or with different people who might not care for his or her welfare and happiness to their standards and to the canine’s usual experience. The thought evokes their contemplative sadness. That they all talk about a burden — for the dog primarily, but also their families and shelters — draws attention to potential deficits in the UK care sector (or its general representation, at least). There seems to be a common belief held by the individuals in the group that the system as its stands lacks the support for interspecies companions to remain together. It is little wonder, then, that they are concerned.

The hope that their dog will precede them in death, universally and individually portrayed within this group, is the optimum outcome. Even though this may bring sadness, grief, and loneliness, leaving a dog behind is not a preferable option. As Reg said of Harvey, he and his wife would “hate to think we would die and leave him to fend for himself.” All the individuals within the project say they would rather accept being alone once their current canine companion has passed than it be the reverse. This represents an understandable concern, as most people would not want to leave their canine companion to an unknown fate.63 Altruistically, and with great consideration Reg, Barbara, John, Mandy, Jean, Laura, and Frank recognize their dogs’ demise before their own as the best outcome — for the dog at least. They think against their own needs, hoping to provide their canine “kin”, in Haraway’s sense of the term, a life safe and fully within their domesticity. Put simply, they do not want their dog to experience the absence, displacement, and grief of losing their companion.

Kheel suggests that “care underscores the role of empathy”, which is significant to consider in this respect.64 Yet, at the time of writing, in the UK there is an unfortunate lack of attention to the extended needs of older people staying with their dogs. 65 Of the 11,300 care homes listed in the UK in 2016, 7,700 are advertised as being “pet friendly”.66 However, the level of friendliness, and what this means, in practice, is misleading. A professed “friendliness” to pets (or companions) does not necessarily mean that a person’s dog or cat can become their co-resident within a care home.67 Unfortunately, little has changed since the market report by LaingBuisson, a business intelligence provider, which produced these findings. Blue Cross, a UK-based charity providing affordable veterinary care and advocat for animal welfare, see this as such an issue that they are constantly pressuring regulatory organizations for all care homes to have a clear companion animal policy.68 They criticize current legislation and advertising as confusing and misleading, and are pursuing ways to work with organizations to ensure this becomes simpler to understand. The ongoing research of Blue Cross in this area notes that forty percent of care homes claim to be “pet friendly”, and that two thirds of older people surveyed said they would be “devastated” if they were separated from their companion animal as a condition of entering residential care. The burden that the storytellers spoke of correlates with this expression of devastation, as one connects to, and informs the other. The research by Blue Cross explains that “pet friendly” can mean anything from the occasional visit by nonhuman animals, care staff bringing their own companion animals into the home, or the presence of a fish tank in a communal area, such as the television room.

Considering these findings, it is little surprise that the people from the Memory Cafés feel anxious about their interspecies futures. Additionally, it is understandable that the burden they discuss relates to the fate of the animal themselves. Realistically, they would enter a residential facility and, if an agreeable alternative is not available, their dog would enter an animal rescue. This is a terrifying predicament for some, and one that would presumably create anxiety and grief, not only because of the separation, but because of the unknown fate of their companion. However, for many reasons and influential factors this is currently not a priority. The day-to-day within care homes is under significant pressure, which leaves little scope for proactivity. Understandably, the pressure is located around stress areas such as finance, and time and human and physical resource restraints, which influence and inform what is achievable and how. There are also recognisable practical difficulties to consider, like who will care for the animal if their person cannot, how many can live together, and are there allergies within the home. Unfortunately, yet understandably, the combination of these complex issues is not seeing a solution for change become a priority for implementation.

In Summary

The stories recounted above demonstrate how the “human-dog relationship is exceptional.”69 They speak to how the dog becomes their human’s companion of choice and significance. This concerns how the interspecies pairings negotiate and engage in synchrony in the everyday to forge a togetherness that is mutually beneficial. Similarly, in Pack of Two: The Intricate Bond Between People and Dogs, Caroline Knapp describes how a dog can become a force for life via the multiplicities present within the relationship. Knapp tells the story of a woman who suddenly found herself living alone after experiencing domestic cruelty: Miranda’s abusive partner leaves her, and Knapp describes how she “felt utterly alone walking into [the now] empty apartment, and she realized at that moment that in fact she wasn’t. She held the dog, and she felt, perhaps for the first time in her life, that she was truly needed, truly responsible for another being, truly in a relationship with another.”70 There are echoes in Miranda’s story of all the stories recounted above, but perhaps especially of Jean’s, who describes Dandy as providing comfort, purpose, and affirmation through her attendance to his daily routine and needs. In return she is in receipt of his reciprocity of care.

Grebowicz notes that “we go on about unconditional love and losing our best friend, but maybe the reason that these tropes fail to describe the experience, that language itself fails and lands us in platitudes, has to do with how profoundly alive dogs are in life.”71 This explains an aspect of why the dogs in the stories have such a great impact on their human companions. An enactment through closeness, proximity, and contact; an attachment that is supportive and purposeful; a representation of looking at the other with the intent to see. Much like in Knapp’s account, through their routine and familiar acts of becoming-with and becoming-kin, dog and human come to rely on each other. This presents a particular “becoming” — a becoming-together — which is significant and present. For Rosie McGoldrick, following Rosalind Krauss’s idea of expansion in the posthuman, this more-than-human approach to understanding “permits and develops” our social and responsive engagement with another species.72 Connectedness is key, and openness to sensing and experiencing connections across species sees relationships develop productively for both.

Looking back and revisiting the archive of the stories several years later, the provocations and narratives of concern for their dogs and their own lives still resonate. The stories act as an anchor to their happening, and the encounter with these people and their dogs who were so open, attentive, and involved. Time has passed and inevitably the relationships have changed, through loss or displacement into care. A sad but inevitable end.

A positive future would ideally explore and create possible solutions to entering residential care with one’s companion animal with relative ease. If the system could learn to accommodate existing human–nonhuman-animal companions, in whatever way, this could make the transition less stressful. An aspiration, where the difficulties of accommodating both the practicalities of the organization and the needs of the individual are overcome. This is not a proposal, as there is absolute acknowledgement of the many complexities and considerations in influence, but rather a desire and optimism for the future. It hopes to make the situation better — but it will take time and resources.73

The Dogs and the Elderly project serves as a reminder of how important it is to hear and give time to the experiences of others. The many facets of this project draw me back continually, as if captive in a loop of experience of listening and hearing, to the stories and their subjects. The project’s formative storytelling sessions are the most significant aspect, as it is here that the experiences and legacies of each interspecies bond are at their most heightened in representation. The beginning of the research, where the telling of the stories took place, is still the most poignant and significant. The stories leave a residual question as to why it is so difficult for these people to share their experiences and feelings in day-to-day life. As a society, are we deaf to the experiences of others, and specifically older people, and those with complex illness? It can be extremely beneficial to listen, so it is useful to find ways like this project to make that happen. The focus on engaged listening is why this project is so important and necessary. These interspecies relationships are the story, they are the research.

Several years on from our time meeting people for the project, my research companion, Oscar, reached the end of his life. When I began writing this article, I was conscious that his time would soon end, and I felt the same impending sense of loss as those who shared their stories. Oscar died aged just over fourteen years on 20 December 2023. In a text indebted to looking back at significant encounters and considering the alive-ness of dogs, of meetings and connected exchanges, I end with fond memories and thoughts of him. A somewhat poignant opportunity to look back on our time of knowing each other, in our relationship and for this project, that heralds the end of our friendship. Another anticipated loss of interspecies togetherness which, sadly, has now become an actuality.

Notes

Social isolation and loneliness are distinct but often linked experiences. One may be socially isolated, which possibly manifests as a feeling of alienation. This may lead to loneliness, a feeling which is more persistent.

Forbes, “Loneliness”, 352.

Smith, “Charting Loneliness”, 38.

Steptoe et al., “Social Isolation”, 5797.

Krause-Parello, “Pet Attachment”, 5.

Krause-Parello, “Pet Attachment”, 3.

Smith, “Charting Loneliness”, 41.

Smith, “Charting Loneliness”, 38.

The individuals involved were asked throughout if they were comfortable, with a reminder to only share what they wished. The situation for the sharing of stories was constructed to allow them to feel valued. This included strategies whereby they were allowed to talk freely, openly, and without restraint; attention was always on the person(s) and their dog, with listening being person-centred, active, present, and receptive.

As the project uses artistic research to engage with others, it does not use the social science methods of interview analysis. Rather, it allows the stories to evolve and exist through creative methodology and interpretation to keep the sentiment with the person and dog to which they speak.

Ingold, Making, 31.

The project is in receipt of the necessary ethical approvals. Additionally, to ensure strict adherence to the organization’s ethical standards, checks with the leads of the Alzheimer’s Society’s Memory Cafés were made throughout.

The appropriateness of the term elderly was part of a discussion and agreement regarding the correct name of the project. This happened at the initiation of the project in collaboration with people engaged through the Memory Cafés in late 2017. The reference to the human in the project’s title was their suggestion, and we decided upon it together through exploring other options and connotations.

The research acknowledges that younger people can also experience Alzheimer’s, but this research specifically is aimed at the older demographic. This is due to the additional complexities of social isolation that advancing age can bring.

After an initial call for participation via Age UK, the East Midlands Alzheimer’s Society made contact to ask that users of their Memory Cafés be involved. This resulted in the work being done with this organization.

Herzog, “Impact of Pets”, 237.

See Haraway, Companion Species Manifesto.

Henceforth, any reference to the term “pet” is as it occurs within citations and in response to literature. The mutuality implied within the term companionship is favoured for the research project.

All images by the author.

The stories inform a sound artwork and video that are shown as companions in gallery exhibitions. The video artwork features only written quotes from the stories, which are edited in sequence (video stills of the quotes are included in this text). The sound artwork includes short, unaltered, excerpts from the spoken recordings. On exhibition, there is a speaker per individual voice, and they are all placed close together as a group. The gallery, as a space that spotlights the artwork, is useful for dissemination. As this text relates to the stories gathered at the start of the process, however, where the unfolding is at its most heightened, there is no image of the sound artwork to offer. The project is still active as new practical components are in development at the time of writing.

Amiot, Bastian, and Martens “Companion Animals”, 552.

MacLean and Hare, “Human Bonding”, 281.

Palagi, Velia, and Cordoni, “Rapid Mimicry”, 2.

Coulter, “Beyond Human”, 204.

Coulter, “Beyond Human”, 204.

Knapp, Pack of Two, 25.

Grebowicz, Rescue Me, 41.

McHugh, Dog, 19.

McHugh, Dog, 124.

Duranton and Gaunet, “Canis Sensitivus”, 514.

Coulter, “Beyond Human”, 204.

Krause-Parello, “Pet Attachment”, 1.

Krause-Parello, “Pet Attachment”, 3.

Herzog, “The Impact of Pets”, 236.

Haraway, Companion Species Manifesto, 12.

Not all domestic human and dog relationships are positive for each species, but for this article mutually productive relationships are the focus.

Coulter, “Beyond Human”, 201.

See Butler, Bodies that Matter.

See Dewey, Democracy and Education.

Borgdorff, “Production of Knowledge”, 50.

See Austin, Things with Words; Butler, Bodies that Matter; Phelan, Unmarked. The performative, for Austin, relates to speech-acts and their truth value. Butler argues that performativity enacts through a gendered and other body, through a constrained series of regularized and repetitive norms. Phelan locates performativity with the political, gendered, and visual body.

The daily walk features largely in one of the stories, as it is a means to be outside of the home, and so has relevance.

Grebowicz, Rescue Me, 35.

Mandy is a pseudonym.

Krause-Parello, “Pet Attachment”, 10.

Amiot, Bastian, and Martens, “Companion Animals”, 555.

Additionally, her name is changed within the project to further protect her position (this was not at her request but felt necessary for the research).

Krause-Parello, “Pet Attachment”, 11.

To the dogs too, but as this is not articulated or explained through the mechanisms of an animal behavioural study, it is not measurable beyond gesture and observation within this research.

Amiot, Bastian, and Martens, “Companion Animals,” 552.

Amiot, Bastian, and Martens, “Companion Animals,” 555.

Coulter, “Beyond Human”, 204.

Of course, not all touch brings pleasure and comfort, particularly if delivered with malice or aggression, and irrespective of being verbal, psychological, or physical. However, for this text the focus is on positive and productive touch between species and bodies.

See Haraway, Staying with the Trouble.

Grebowicz, Rescue Me, 17.

Derrida, On Touching, 47.

Benjamin, One-Way Street, 50–51.

Yuhas, “Pets”, 31.

Nagasawa et al, “Oxytocin”, 334.

Nagasawa et al, “Oxytocin-Gaze Positive Loop”, 334.

Amiot, Bastian, and Martens, “Companion Animals”, 556.

Kheel, “Communicating Care”, 45.

Within the parametres of this study it is impossible to say if this would be the same for dogs. Due to the nature of dogs’ capacity for synchronicity, companionship, and attachment, however, one may presume sentiment to be the same.

Kheel, “Communicating Care”, 45.

A simple solution, could, perhaps, see existing interspecies companions remain together within residential facilities, but there is much to consider to make this achievable.

LaingBuisson, “Care of Older People: UK Market Report” 2016.

It is acknowledged some do allow this, but at extra and often unaffordable cost to most.

“All Care Homes Should Have a Pet Policy says Blue Cross”, Blue Cross 23 April 2021, https://www.bluecross.org.uk/news/all-care-homes-should-have-a-pet-policy-says-blue-cross. This research-informed directive is ongoing and regularly updated with most recent details and developments on the website.

Nagasawa et al, “Oxytocin-Gaze Positive Loop”, 334.

Knapp, Pack of Two, 203.

Grebowicz, Rescue Me, 34.

McGoldrick, “Artist Ethics”, 3.

Organizational and sector difficulties are acknowledged, and this is in no way meant to apportion blame.

Works Cited

Amiot, Catherine, Brock Bastian, and Pim Martens. “People and Companion Animals: It Takes Two to Tango.” BioScience 66, no. 7 (2016): 552–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biw051.

Austin, J. L. How to Do Things with Words: The William James Lectures Delivered at Harvard University in 1955. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2011.

Benjamin, Walter. One-Way Street and Other Writings. Translated by Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter. London: Verso, 1997.

Borgdorff, Henk. “The Production of Knowledge in Artistic Research.” In The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts, edited by Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson, 44–63. London: Routledge, 2011.

Butler, Judith. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Coulter, Kendra. “Beyond Human to Humane: A Multispecies Analysis of Care Work, Its Repression, and Its Potential.” Studies in Social Justice, 10, no. 2, (2016): 199–219. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v10i2.1350.

Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. London: Bloomsbury, 1994.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Derrida, Jacques. “The Animal That Therefore I Am (More To Follow).” Translated by David Wills. Critical Inquiry 28, no. 2 (2002): 369–418. https://doi.org/10.1086/449046.

Derrida, Jacques. On Touching — Jean-Luc Nancy. Translated by Christine Irizarry. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005.

Dewey, John. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: Macmillan, 1916.

Duranton, Charlotte and Florence Gaunet. “Canis sensitivus: Affiliation and Dogs’ Sensitivity to Others’ Behavior as the Basis for Synchronization With Humans?” Journal of Veterinary Behavior 10, no. 6 (2015): 513–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2015.08.008.

Forbes, Anne. “Caring for Older People: Loneliness,” BMJ: British Medical Journal 313, no. 7053, (1996): 352–54. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.313.7053.352.

Grebowicz, Margret. Rescue Me: On Dogs and Their Humans. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021.

Haraway, Donna J. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Herzog, Harold. “The Impact of Pets on Human Health and Psychological Well-Being: Fact, Fiction, or Hypothesis?” Current Directions in Psychological Science 20, no. 4 (2011): 236–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411415220

Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge, 2013.

Kheel, Marti. “Communicating Care: An Ecofeminist Perspective.” Media Development (2009): 45–50. https://waccglobal.org/communicating-care-an-ecofeminist-perspective/.

Knapp, Caroline. Pack of Two: The Intricate Bond between People and Dogs. New York: Random House, 1998.

Krause-Parello, Cheryl A. “The Mediating Effect of Pet Attachment Support Between Loneliness and General Health in Older Females Living in the Community.” Journal of Community Health Nursing, 25, no. 1 (2008): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370010701836286.

McHugh, Susan. Dog, London: Reaktion Books, 2004.

McGoldrick, Rosemarie. “Artist Ethics and Art’s Audience: Mus Musculus and a Dry-Roasted Peanut.” Arts 12, no. 4 (2023): 174 https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040174

MacLean, Evan L. and Brian Hare. “Dogs Hijack the Human Bonding Pathway: Oxytocin Facilitates Social Connections Between Humans and Dogs.” Science 348, no. 6232 (2015): 280–81. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab1200.

Nagasawa, Miho, Shouhei Mitsui, Shiori En, Nobuyo Ohtani, Mitsuaki Ohta, Yasuo Sakuma, Tatsushi Onaka, Kazutaka Mogi, and Tkefumi Kikusui. ”Oxytocin-Gaze Positive Loop and the Coevolution of Human–Dog Bonds.” Science 348, no. 6232 (2015): 333–36. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261022.

Palagi, Elisabetta, Velia Nicotra, and Giada Cordoni. “Rapid Mimicry and Emotional Contagion in Domestic Dogs.” Royal Society Open Science, 2 (2015): 2150505.https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150505.

Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. London: Routledge, 1993.

Smith, Kimberley. “Charting Loneliness,” RSA Journal 165, no. 1 (5577) (2019): 38–41. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26798454.

Steptoe, Andrew, Aparna Shankar, Panayotes Demakakos, and Jane Wardle. “Social Isolation, Loneliness, and All-Cause Mortality in Older Men and Women.” PNAS 110, no. 15 (2013): 5797–801. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1219686110.

Yuhas, Daisy. “Pets: Why Do We Have Them?” Scientific American Mind, 26, no. 3 (2015): 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamericanmind0515-28.