Untamed Nature

A Sociocultural History of the Modern Dutch Cat

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.13534

Keywords: Cats; Human–animal relations; The Netherlands; Avant garde artists; Class relations; Pet-keeping

Email: h.ronnes@uva.nl

Email: harry.reddick@ahk.nl

Humanimalia 14.1 (Fall 2023)

Abstract

The cat is now one of the most popular pets in the Netherlands, but it was once much maligned. The development of the European cat as a pet in general followed a trajectory from outcast with wealthy ladies as its sole ally, via idiosyncratic nobles and romantics, to the beloved and subversive muse of artists and creatives. The history of the French, English, and American cats has received attention in the past, but that of the Dutch cat has not. This latter history took a somewhat different turn, as is shown in this article. In the Netherlands the cat was adopted in the last quarter of the nineteenth century by the bourgeois and urban elite as well as by socialists, feminists, and avantgarde artists. The class-adjacent cultural tug of war that ensued about the cat was eventually won by the latter groups. These counter-cultural movements saw the cat as emblematic of their cultural position as creatives and people at the edge of society, linking the recalcitrant and enigmatic character of cats to their own idiosyncrasies. This association was to persist in the Netherlands and is mirrored today in the mainly left-wing political orientation of the Dutch cat-owner.

While the cultural status of cats has been on the up and up for the past century and a half, their ecological reputation has recently taken a hit.1 Despite their overwhelming popularity as media icons, cats have not — in stark contrast to almost every other living animal — benefited from the growing public interest in nature and nature conservation. Indeed, the opposite is true: this recent upsurge in (media) attention for ecology and sustainability has been quite detrimental to the domestic cat’s reputation, as evidenced by the ongoing debate on the harm caused by domestic cats to nature and biodiversity. Both academic scholarship and bestselling books, such as Cat Wars: The Devastating Consequences of a Cuddly Killer and The Lion in the Living Room: How House Cats Tamed Us and Took Over the World (both published in 2016), not to mention the media, have recently begun to frame the domestic cat as a threat to wildlife.2 In the Netherlands, this discussion is fuelled by the “Huiskat Thuiskat” [House Cat, Indoor Cat] foundation, which, backed by various members of the Dutch scientific community, seeks jurisdiction that will prohibit cats from roaming freely outdoors.

These accusations against cats are not new: the main reason for the cats’ late adoption as pets in the late nineteenth century, was their penchant for killing birds. Despite this bad press, legislation protecting cats from abuse or murder was introduced in most Western European countries, including the Netherlands, in the second half of the nineteenth century. This was an important milestone in the cat’s long and winding journey from maligned scapegoat to beloved companion animal. The history of this journey — and of the shifting human–animal relationship it signifies — has been explored in various Western contexts, but so far there has been little sustained investigation into the history of the Dutch cat. This is surprising given the socio-political context of the Netherlands, through which an idiosyncratic type of cat began to emerge. Its changing position in nineteenth-century society is to an extent congruent with that of French, British, and American cats, as discussed by Kathleen Kete, Harriet Ritvo, and Katherine Grier, in that it is intertwined with issues of class and cultural production.3 However, the agents of change in the Netherlands — artists, both traditional and avantgarde, members of the elite, and prominent socialists and feminists — gave rise to a qualitatively different and peculiarly Dutch idea of the cat, which has proven to be exceptionally robust and enduring. This cultural construction notwithstanding, however, there are also aspects of cats’ behaviour which, as we will show, would allow them to be characterized as agents of change in their own right. After all, cats are endowed with a certain autonomy that makes them unpredictable and perhaps less subject to the whims of the systems organizing human social and cultural life than, for example, the dog (the cat’s principal rival for human affection), might be. Thus, it would be a mistake to understand the question of agency in the human–animal relations presented hereafter as a one-way street: it is precisely the specific behavioural character of cats that underpins their adoption by the avantgarde and socialist pillar of Dutch society. Based on big data analyses of historical newspapers and the study of contemporary literature and art, this article analyses human–feline relationships and traces the birth of a quintessentially Dutch cat some 150 years ago. The next section will start with a history of the cat in the pre-nineteenth-century Dutch Republic.

Pawing the Line: Early-Modern Dutch Cats

Several behavioural and affective qualities of cats as a species have ensured that there has always been a small but dedicated core of followers in the Low Countries.4 Their glossy fur drew admiring looks; their ears and big eyes were considered charming. Especially the fact that they were useful in the household and in the barn as hunters of mice and rats was appreciated. Supporters further maintained that cats have a social (if enigmatic) side. They love being petted by people, which they show by pressing up against passers-by. Given the cat’s reputation for cleanliness, this may be a temptation for the passer-by, but one which does carry the potential risk of transferred zoonotic disease. Others simply felt that the cat was as close as one could get to a lion or a tiger without leaving Dutch shores: a cuter, miniature version of such exotic foreign fauna. But these positive evaluations should be regarded as exceptions to the rule that cats faced fierce opposition. Their already vulnerable position was made even more precarious in the late twelfth century, when the Church turned its back on cats, stigmatising them as a symbol of evil.5 This led to a centuries-long cultural association of the cat with the diabolical, carnal, and feminine.

Erik Aerts, author of two recent studies on the history of the Dutch cat, argues that cats’ reputation did begin to change somewhat in the seventeenth century. While the uneasy connotations of the cat with devilry and witchcraft — with the latter also being understood as a byword for a pernicious sexuality and promiscuity — persisted well into the nineteenth century, this did not prevent burghers in the Dutch Republic, who had just gained their independence from Spain and great wealth through trade and colonialism, from welcoming cats into their lavish townhouses. This is evident from paintings of children playing with cats alongside domestic scenes with a cat by the fireplace. It is quite possible that, within the many prosperous towns of the Dutch Republic, the tentative rise in the cats’ status within the household context indeed started somewhat earlier than elsewhere.6 Apart from this early form of domesticity evident in the genre paintings, the relative religious freedom and the radical enlightenment generally associated with the Dutch Republic — though historians have begun to nuance this image7 — may also have contributed to a somewhat more cat-friendly climate.8 Free thinkers such as Constantijn Huygens and Balthasar Bekker fiercely criticized superstition in their works and both referred to cat fables when doing so.9

The advance of the cat as a pet nevertheless took an erratic course, one tied into societal processes of change — and who was afforded the agency to effect it — within Dutch history. Cat-haters remained in the majority in the Low Countries, with their vitriol not only directed at their feline foes, but at their owners — people who, in the eyes of their critics, were excessively and obsessively attached to their cats. These perceptions persisted into the eighteenth century. In literature, Gysbert Tysens’ publication of the popular poem “Op de dood van een poesje” [“On the Death of a Pussycat”] — a rhythmic and witty piece in which a woman’s love for a cat is ridiculed at length — is fairly typical.10 Betje Wolff and Aagje Deken’s 1787 epistolary novel Letters from Abraham Blankaart provides another example of a cat — a pussycat walking on mama’s piano — being outcast with wealthy ladies as their sole ally. Incidentally, and indicative of the way in which cat maltreatment was still downplayed, in the novel the drowning of a cat is dismissed as unimportant.11

In the encyclopaedias of the time, entries relating to cats are rife with anthropomorphic references to their many negative qualities, which are typically coded as feminine: falseness and disloyalty are mentioned remarkably often. Johannes le Francq van Berkhey begins the entry on the cat in his Natural History for Children (1781) as follows: “The cat is a very treacherous, unfaithful and thieving animal, which cannot be tamed sufficiently, either by caresses or treats, nor by beatings or locking up, that she will leave off scratching and stealing.”12 Van Berkhey followed the example of Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon in France, who in his famous Histoire Naturelle (1749–1782) was similarly scathing when it came to cats.13 However, Buffon’s and van Berkhey’s by-then somewhat old-fashioned, clichéd representations of the cat as devilish and licentious, evoked a counter-reaction. Especially purebred cats were increasingly defended and adopted by the (intellectual) elite and nobility. François-René Chateaubriand, Horace Walpole, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, for instance, were all famous cat-lovers.14 As was Isabelle de Charrière (aka “Belle van Zuylen”), the eighteenth-century Dutch (and later Swiss-based) author, known for her novels and letters which cast a critical eye on contemporary society, including pre-Revolution France. Charrière might have been influenced by Rousseau in her love of cats. (Indeed, her entire oeuvre of novels, plays, and letters may arguably be read as an ambiguous response to Rousseau, whose Confessions she helped publish.) Charrière’s love for dogs is well known, as shown in a recent publication,15 but in her letters she also regularly mentions the presence of a cat in her house.16 This partiality on the part of nobles such as Charrière went further than a typical “aristocratic affectation”.17 Cats appealed to noble outsiders because they were aloof and elegant misfits just like them. For de Charrière, the cat was also a symbol with which she rebelled against the nobility as a social group and the class restrictions that mainly affected women. This is apparent, for example, from her novel Lettres de Mistriss Henley, whose eponymous protagonist, feeling trapped in her husband’s ancestral country house, takes in a cat. While she removes the portraits of her husband’s family, the cat scratches the furniture. For the human protagonist, fleeing is impossible, but the cat, unrestricted by human obligations of marriage and class, seizes the first opportunity to run away and leave the suffocating place, never to return.18

Compared to dogs, cats were much more rarely portrayed in the eighteenth century, whereby William Hogarth’s The Graham Children serves as a relatively famous European exception. Katherine Rogers believes that this is because a cat could not contribute to the status of the owner, again placing the idea of cats and their ownership into a tangled perception of class dynamics. The cat, she writes, “was neither an expensive, highly bred animal, nor one that could plausibly be shown gazing adoringly up at its human patron.”19 Various Dutch artists produced further exceptions, e.g. the early Dutch cat portrait “Two Children with a Cat” (1630) by Judith Leyster (fig. 1); Karel du Jardin’s etching “Sleeping Dog and Cat" (1652–59) (fig. 2); or Aert Schouman’s portrait of Maria Catharina van der Burch and Hendrik baron van Slingelandt’s cat who lived at their Zuydwind estate south of The Hague. The latter portrait indicates the slow rise of a less discursive love for cats on account of the Dutch elite. The watercolour portrait shows an apparently very ordinary cat sporting a pink bow. The affectionate caption reads: “Our cat, born at Zuydwind Anno 1744, died 1761”.20 Although, as we have seen, there is plenty of evidence that in the eighteenth century it was still predominantly “outsiders”, including women and certain members of the noble elite, who are associated with cats, this portrait hints at a broader, familial adoption of cats by people of means or education. A self-portrait of the engraver and painter Hendrik Spilman with his wife Sanneke van Bommel, their two children and a cat (fig. 3), similarly speaks of this broader appreciation of cats.

Figure 1: Judith Leyster, Two Children with a Cat, ca. 1630. Oil on canvas, 61 × 52 cm. Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2: Karel du Jardin, Sleeping Dog and Cat, 1652–1659. Etching, 300 × 311 mm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Object no. RP-P-H-S-49. Public domain.

Figure 3: Hendrik Spilman, Self-Portrait with His Wife Sanneke van Bommel, Their Two Children [and a Cat], 1761–1784. Oil on canvas, 37 × 30 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.Object no. SK-A-1583. Public domain.

Cat Welfare: Rules and Rights

The integration of cats into families in the upper echelons of society continued into the nineteenth century. In B. A. Alewijn’s 1837 poem “De roode kat van den Heer Abbing vertelt haar wedervaren aan eenige andere katten” [Mr Abbing’s Ginger Cat Recounts Her Adventures to Some Other Cats] the protagonist, a cat named Rozette, tells her cat friends of the love she received having been accepted into the Abbing family after running away from her previous master, whose cheeses in the attic she had defended from mice.21 Rozette tells her story on the bleachfield, where she and her audience are safe from the maids and the neighbour, whose dislike makes it clear that, Rozette’s recent positive experiences notwithstanding, cats were certainly still not to everyone’s liking. Nevertheless, cats were now often framed as a victim rather than as an aggressor, which led to greater enfranchisement. The legal emancipation of cats through animal rights legislation — which proved important for the gradual improvement in the position of the cat — was much slower in the Netherlands and more ponderous than in France and the UK. In order to avoid being perceived by its European neighbours as a barbaric, “uncivilised society”, the Dutch state eventually bowed to public pressure.22

This pressure predominantly came from those who cared most about the overall push towards the education and refinement of Dutch society: the elite. From the eighteenth-century eccentric noble’s flirt, to a more bourgeois, familial patronage in the early nineteenth century, the engagement of the social elite with cats in the latter half of the nineteenth century was fuelled by a “civilizing offensive”. Ambitions regarding animal welfare and a civilizing of the people dovetailed in efforts to abolish popular games such as “katknuppelen” (“clubbing cats”), which consisted of a cat having to get escape from a barrel which was being smashed by boys with clubs. Animal welfare was initially instigated by private initiatives (as was the case in the UK and France) such as The ’s-Gravenhaagsche Vereeniging tot Bescherming van Dieren [The Hague Association for the Protection of Animals], founded in 1864, with King Willem III as one of its patrons. The King was also entreated to help establish the Sophia Society (named after Queen Sophia), which pursued similar animal protectionist goals. The first animal shelter or Toevluchtsoord voor Noodlijdende Dieren [Refuge for Distressed Animals] was established in 1878 by six wealthy ladies from The Hague, having again taken their cue from a similar British organization. Initially catering only to stray dogs, cats became part of the organization’s remit in 1893. Annual figures from 1893–94 indicate that care of cats was not the primary task of the shelter. Rather, quite the opposite appeared to be the case. Of the 117 animals brought in by the police and private individuals, 114 were euthanized. This was done by means of gas: infinitely more humane, it was said, than drowning in a well, which was common.23 In 1896, a “painless suffocation room” was opened in Haarlem for stray and sick animals, a service that was free for the poor, while the well-to-do were asked to pay a small fee.24 Intertwined with the shift in the relationship with animals such as cats, then, was the public response to the problem of strays and the nuisance they caused, regarded at the time as a serious matter of public health. As early as 1885, an Amsterdam resident was concerned about the large number of dead stray animals in the capital and wrote to the newspaper to ask whether this should not be a matter for the government, especially with a view to the deterioration of the water quality in the canals. The start-up subsidy provided by municipalities for dealing with the problem seems to suggest it was indeed considered a governmental concern, in keeping with the ongoing civilization agenda pushed by the elite.25

Apart from a preoccupation with animal maltreatment by the lower classes, a significant part of the discussion on animal welfare at the end of the nineteenth and into the twentieth century focused on animal testing. Cats were still commonly used in the laboratory for excruciating tests involving the administration of arsenic, cocaine or “a few drops of sulphur sodium solution”. In neighbouring countries, the legitimacy of animal testing had been a matter of public dispute from as early as the eighteenth century.26 Dutch support for foreign critics such as Jeremy Bentham and Arthur Schopenhauer came from the anarchist philosopher Felix Orrt.27 Orrt’s philosophy fit within a broader movement of socially-engaged Protestant thought, principal proponents of which included the highly influential Protestant theologian and Prime Minister Abraham Kuyper, as well as one of the best known Dutch socialists, Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis. Kuyper’s impact on Dutch society cannot be overstated. Singlehandedly responsible for the main schism within the Dutch Protestant Church, the founder of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the newspaper De Standaard, and the Anti-Revolutionaire Partij, the first political party in the Netherlands, Kuyper is regarded as the prime mover in the “pillarization” [verzuiling] of Dutch society.28 He was also a member of the Society for the Protection of Animals (Dierenbescherming) and openly opposed vivisection.

Nieuwenhuis, who represented the opposing, socialist “pillar” of Dutch society, was also active in the animal welfare movement. His perspective that animals could be worthwhile subjects of solidarity (extending his politics beyond just human concerns) was influenced further by the particular love he had for his own cats. In a letter to his daughter Johanna written in 1895 he voiced his belief that cats’ solidarity with each other was an example for humanity.29 His electorate, however, did not always share his opinion on this point. The improvement of the situation of the Dutch cat met with protest from people — not seldom socialists — who feared that more money would be spent on the welfare of animals than of humans. With some regularity indignation was expressed in the media at what seemed like excessive care for animals at a time when many poor still lived in appalling conditions and worked longer hours than the pampered animals.30 When the first Dutch animal shelter opened, the Algemeen Handelsblad noted that while public opinion had shifted noticeably in favour of animal welfare, it was still not uncommon to encounter incredulity and indignation at the fact that dogs and cats now had their own refuge in the Hague while “many a member of that much higher species, man, suffer misery and deprivation.”31 Proponents of animal testing saw the anti-vivisection movement as decadent and accused its members of making a mockery of the scientific process. They portrayed the activists as weak and effeminate, as soft-hearted housewives with overfed, indolent, and overindulged “favourite kitties”.32 The activists they had in mind were not the ones engaged in parliamentary debates, but formed part of two groups at the edges of society that became involved in the anti-vivisection movement: feminists and members of the so-called petites religions.33 With the progressive secularization of society there was room for the rise of these “small religions” (vegetarianism, esoterism, etc.), whose members interpreted evil differently than most of the dominant Christian doctrines, and thus had a different agenda — including the fight against animal abuse. Feminists, seeing a link between their own liberation and that of animals, were also actively involved in the anti-vivisection movement. They raised their voice in public lectures and through fiction. Marie Daal (a pseudonym for Caroline van der Hucht-Kerkhoven) introduced female heroines into her anti-vivisection novels who are confronted with the reality of vivisection and the abuse of cats, and, as a result, take up a more active social role in trying to prevent this maltreatment than was common for women at the time.34 This indicates again the subtle influence cats had upon sociocultural power relations, rather than simply being the beneficiary of charitable human actors.

The combination of animal welfare institutions and philosophical objections to testing culminated in demands for tougher legislative precautions to the issue of animal protection. Such legislation duly — if gradually — surfaced against this backdrop. The amendment for the “provision against rabies” was an important first step. Passed in 1875, the amendment determined that the chaining up of cats was antithetical to their nature (although this did not put a complete stop to the widespread practice). The “laws of nature” thereby demanded a law of society that guaranteed that cats could roam around freely. The same year saw the first “Animals Act” criminalizing the deliberate maltreatment of cats, which resulted in numerous fines reportedly being given to less “civilized” members of society who were guilty of killing or abusing cats. In March, De Tijd reported that a man and a boy had been sentenced to a month and two weeks in prison, respectively, for stealing two cats.35 Four years later, in July 1879, the same newspaper printed a letter from a reader in Amsterdam complaining about poor adherence to the terms of the Act, suggesting that animal protection was not yet a high priority. According to the author, even city officials and police officers were guilty of mistreating cats.36 A solution was drawn up in order to further encourage compliance with the new laws. Local animal protection departments negotiated a bonus scheme for its staff, who would receive a cash bonus for every report that led to a conviction. Concurrently, unofficial state constables were appointed to monitor compliance with the law, while financial incentives for police officers proved effective.37

Artists’ cats

Artistic manifestations of cat-orientated sentiment also provide a barometer of the changing opinions of cats towards the end of the nineteenth century. One of the most notable depicters of cats, who not only cherished but also painted them incessantly was the Amsterdam-based painter Henriëtte Ronner-Knip (see fig. 4). Amid the trend of organizing cat shows from around 1890 (following the example, again, of the English, and the likes of the Crystal Palace shows), her romantic paintings focused on the purebred cats of her wealthy patrons — Siamese and long-haired cats such as Angoras and Persians — in a bourgeois salon (sometimes accompanied by their bourgeois mistresses).38 Ronner’s work was popular all over Europe, but especially among the British nobility and wealthy merchants. She was said to compete only with the greatest painter of the nineteenth century, Rosa Bonheur, who, like Ronner, devoted herself to animal portraits.39 She demonstrated a canny entrepreneurial instinct by orientating her genre painting towards the changing art market, as wealthy buyers (who apparently wanted their own luxurious lives reflected back at them) commissioned and paid for many cat paintings. Ronner’s cats and their stately salons thus became cemented as the interior par excellence of a social group who now enthusiastically embraced the cat as pet.40

Figure 4: Henriëtte Ronner, Cat with Kittens, 1844. Oil on panel, 52.5 × 39 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Object no. SK-C-163. Public domain.

Compared to current house cats, Ronner’s specimens look a lot more dignified. A then-new category of “lost and found” newspapers advertisements gives the impression that the missing cats of members of society rich enough to pay for such an advertisement were all decked out with bells and bows.41 To further gloss over their rougher sides, these cats were kept indoors as much as possible and spent part of the day and night in a basket. Street cats on the other hand were much scruffier than twenty-first-century cats: they were likely to be malnourished, thin, less vibrant in terms of colour and markings, often disabled, with open wounds or infested with fleas, and socially cautious or lacking in agency. It is said that Ronner once placed an advertisement for new models, but that when she was offered “normal” cats, she firmly declined the offer.42 Clearly, Ronner felt her large audience of Amsterdam notables would have turned down the cats of the streets and back-alleys of the Dutch capital.43 In declining, Ronner fits uneasily among the bracket of artists working in cat-focused or at least cat-featuring paintings, who considered other cats — and specifically not the purebreds — as suitable for representation. The street cat was the mascot for avantgarde artists, the painters and writers of the day, coalescing most strongly from the 1880s onwards. A straight line can be drawn from the eccentric eighteenth-century misfit noblemen to the avant-garde painters and writers who were active a century later. The fact that Ronner, as well as her clientele, and the upper echelons of society were active in promoting animal welfare also had its roots in the eighteenth century, though these belonged to a completely different lineage of cat-lovers than the avantgarde artists, namely the (noble) elite with an interest in cats. This highlights the double identity of the modern(ist) cat: on the one hand wild, misunderstood, and ostracized, on the other domestic, aestheticized, and hygienic. This is reflected in the specific type of cats — scruffy street cats versus pampered purebreds — adopted by the two groups.

Dutch avantgarde artists looked towards France for inspiration for cat-art, where modernist painters such as Monet, Renoir, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec all painted cats in significant roles, either as protagonists or at least as sidekicks.44 Although initially shocking and much parodied, especially Manet’s once-controversial Olympia, a parody of Titian’s Venus of Urbino, had a profound effect, and the black cat depicted in the painting became a beloved model, embodying a threefold sexual meaning: through the cat’s proximity to the naked courtesan, as a visual pun (a literal pussy in the boudoir); and through its erect tail. It wasn’t only French painting that Dutch avantgarde artists drew inspiration from; they also turned to literary cats. Following from Ludwig Tieck’s 1779 adaptation of Puss in Boots, numerous Romantics across the literary world had followed in his footsteps: Wordsworth, Pushkin, Chekhov, and Poe are some of the giants of nineteenth-century world literature who gave the cat a place in their oeuvre. Champfleury’s Les Chats not only discussed the sexual connotation of the cat, but also proclaimed that it is mainly women, poets, and artists — in other words: sensitive people — who understand cats. That Manet’s black cat became a mascot of the Parisian Bohemian, however, had as much to do with the Rodolphe Salis’s illustrious theatre café and cabaret in Montmartre, Le Chat Noir. The famous poster by Theophile Steinlen, in which the haughty and independent cat was prominent, established an even stronger association between cats and art within the broader French social context.45 Meanwhile, Charles Baudelaire, another prominent cat-loving poet, cultivated maladjustment and impassive and elegant dandyism, which suited the autonomous and aesthetic feline perfectly.46

In the Netherlands, in part through the influence of these European artists and writers, the association between avantgarde artists and cats was similarly pronounced, but it grew to take on a distinct character. The influential group of avant-garde literati, poets, and artists who comprised the counter-cultural scene of late-1880s Amsterdam, known collectively as the “Tachtigers” (the “Eightiers” or the “Movement of Eighty”), also adopted the cat as their figure, albeit without the strong sexual connotation of the cat in contemporary French art. For the Tachtigers, the cat served mainly as a de facto animal representative, with its idiosyncratic nature seemingly the perfect embodiment of their own isolated, misunderstood genius.

Cats at the Vanguard

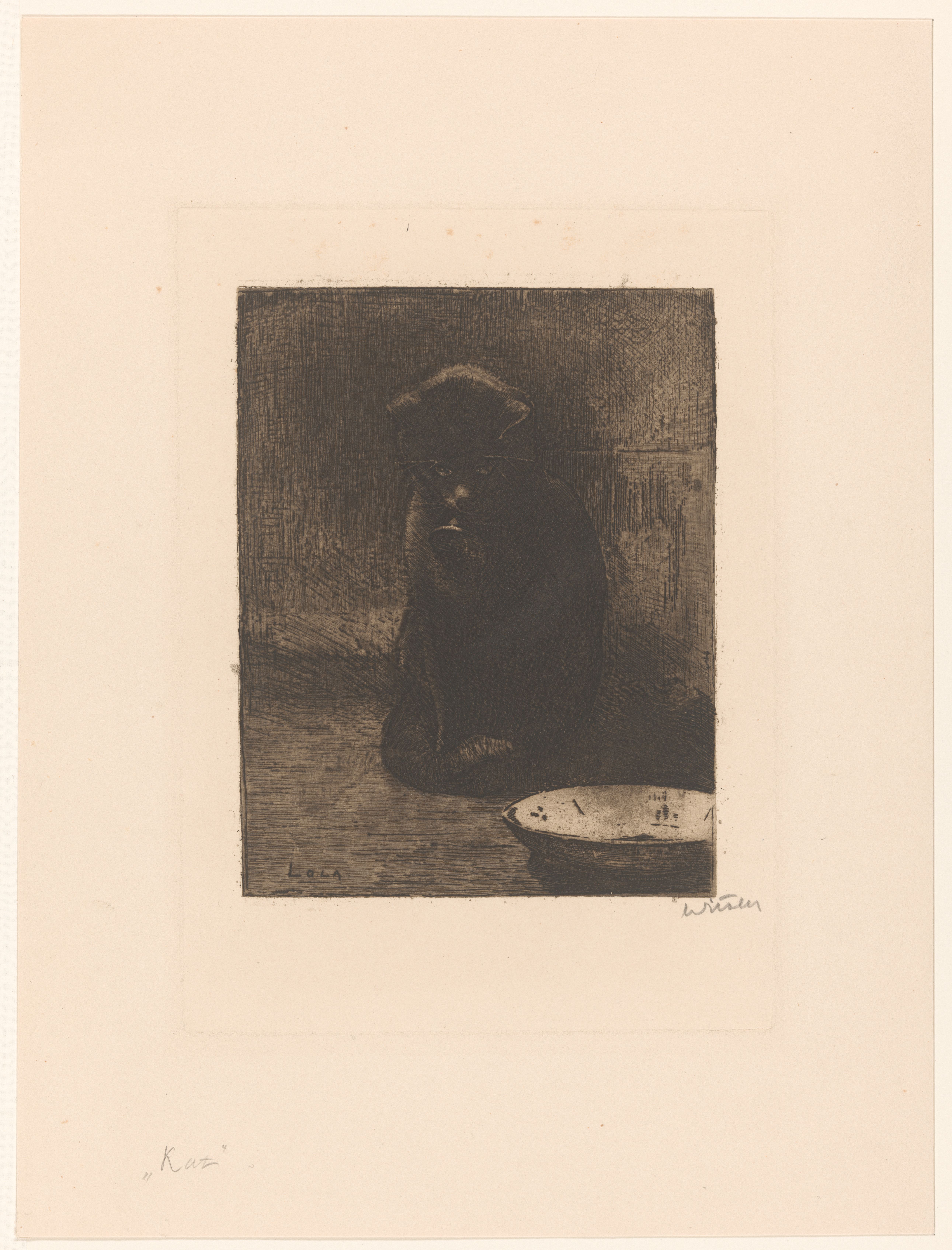

The Tachtigers’ love of cats is documented from their earliest gatherings. The minutes of the first editorial board meeting of De Nieuwe Gids [The New Guide], the journal founded by the collective to parody the established literary journal De Gids, which had refused to publish their work, mention the presence of a cat. The entire editorial board — with one possible exception — owned or co-habited with a cat. Others associated with the movement, such as the well-known members Jac van Looy (1855–1930), Lucie Broedelet (1875–1969), Willem Witsen (1860–1923), and more besides, made references to cats in letters, stories, diary fragments or featured them in their paintings or photos. Witsen, for example, kept a cat in London in the 1890s.47 And in 1903 Witsen writes to his son Pam thanking him for a “beautiful little story” about a cat.48 Witsen’s love for cats would spill over into etchings and drawings (see fig. 5), and he also photographed the poet Lucie Broedelet with a cat. Tholen’s 1889 painting Slachthuis [Slaughterhouse] featured a curious cat stepping beyond the threshold of the titular scene. George Hendrik Breitner’s Lady with a Cat (1883) is probably the best-known cat work amongst the Tachtigers’ output, but it is certainly not the only one in his oeuvre (see fig. 6). He produced countless photographs and drawings of cats. As a kind of signature, a drawing of a cat is prominently displayed in the background of Breitner’s self-portrait. Breitner may also have taken the first Dutch post-mortem photo of a cat.49

Figure 5: Willem Witsen, Poes Lola [Lola the Cat] ca. 1887–88. Etching, 249 × 179 mm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Object no. RP-P-1941-269. Public domain.

Figure 6: George Hendrik Breitner, Marie Jordan Breitner with a Cat in her Lap, c. 1885–c. 1905. Gelatin silver print, 300 × 311 mm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Object no. RP-F-00-588. Public domain.

Attitudes towards cats had now shifted significantly, and this is evident in the story “The Death of My Cat” by Jac van Looy, published in De Nieuwe Gids. Although the title is almost identical to the aforementioned poem written a century earlier by Tysens ridiculing a feminine (or effeminate) love of cats, van Looy’s autobiographical piece demonstrates a completely different attitude towards the cat. His story describes a personal and tender relationship with a beloved pet, whose death has left the writer bereft. The fact that the cat murderer was a young, brash and insensitive lower-class boy adds further complexities of class positioning to both the tale and cat historiography.50

Cats began to appear in other Tachtigers’ literary works too. Frederik van Eeden’s now-canonical “Little Johannes” featured a house cat Simon deeply admired by eponymous protagonist.51 This was not the last of van Eeden’s dalliances with cats: his Amsterdam diaries are filled with “fat cats”; cats joined a family outing on the Banham country estate; a waitress at a café-restaurant is accosted by playful cats; his children find a litter of kittens in Frankfurt.52 On a further occasion, cats even penetrate his subconscious: in his private “Dream Book” he describes an erotic dream in which a man’s genitals take on the form of a cat that scratches and bites him. Such sexual symbolism is reminiscent of the French cat, but, importantly, it does not feature in his published works.53

Perhaps most notably, the Tachtigers’ cat-obsession becomes clear in the malleability of language itself when put to the services of feline metaphors, in which the Tachtigers were adept.54 In addition to well-known cat-related idioms such as “de kat uit de boom kijken” (lit., “to stare the cat out of the tree”, equivalent to the English “wait and see which way the cat jumps”), all kinds of self-invented expressions and metaphors abounded. In the Tachtigers’ hands, cheeks can be as “soft as cat fur” (according to Herman Gorter); people may be “as pretty as a kitty” [poes-mooi] (Willem Kloos); according to Albert Verwey, Lodewijk van Deyssel’s arguments are all mixed up as if “the cat had been playing with them”.55 Jacob Israël de Haan describes his own “little letter” to van Deyssel as “just like the squeak of a pussycat”.56 Ill-advised critics, according to Kloos and Verwey, seemed like a “collection of trapped mice” who will soon “be for the cat”.57 Finally, cats represent both the world of critical reception — Willem Kloos sketches an idyllic mise-en-scène of a critic at an open window in the evening watching two cats, spellbound — and a playful way to evoke frustrated sexual arousal, again expressed only privately in a diary.58 Cats, then, represent the cerebral and playful counter-cultural scene that the Tachtigers helped define at the turn of the twentieth century. The Tachtigers eschewed the domestic-bourgeois cat that Ronner built a career on and which was especially popular in the UK, as well as the association with femininity and sexuality that remained commonplace in French cultural settings.

Legacies

The association of cats with the avantgarde which the Tachtigers had help to foster would persist in the Netherlands, and cats and their mysterious nature remained a recurring theme in literature, art, and aesthetic debates in counter-cultural circles in the twentieth century. Meanwhile, the nobility and the social elite in general lost their interest in cats and turned their attention to dogs instead. This also meant that the common cat won out over the purebred cat: the bows that had adorned the chic nineteenth-century specimens disappeared in the twentieth century, even as paintings of stately cats against the background of tasteful interiors gave way to modernist representations, the most famous being Bart van der Leck’s The Cat (1914). This does not mean, however, that the ordinary cat was not regarded as an elegant creature: she was chic by nature. The short story “Imperia” by Louis Couperus (regarded as a Tachtiger by some, as the Dutch Proust by others), published in 1910, perfectly encapsulates this development. Set against the sunny backdrop of Nice with its beautiful city palaces and gardens, “Imperia” tells the tale of the author’s eponymous street cat. A French friend of his, a femme de lettres, is amazed: “How can you,” she asks, “have such an ordinary chat-de-gouttière! You, for whom everything must be so refined!” The narrator replies that Imperia is not at all ordinary but “witty, graceful, and feline”.59 He must have understood very well what his friend meant: to her surprise, Couperus has taken a liking to a mundane alley cat instead of a beautiful long-haired Angora. Couperus rejects the distinction between these two types of cat and pretends that it was not Imperia’s breed but her individual characteristics that were the subject of conversation.

While Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis’s ideas on animal welfare were, as we have seen, not always supported by his colleagues and the electorate, a few decades later this was significantly different. In the 1920s and 30s animal welfare ranked high on the socialist agenda; the most prominent socialist advocate for animal welfare was the influential politician Henri Polak (1868–1943).60 While they were actively involved in nature conservation, within which animal protection was a key issue, other parties largely remained silent on the subject. Politically and otherwise, the members of the elite had turned their back on the cat. The nobility’s favourite pet was now the dog (in many ways the anti-cat); the bourgeois urban elite had also lost their interest in the purebreds and no longer adorned their homes with cats or cat art.

Fast-forward to the 1950s and 70s, and an endless line of renowned Dutch authors, including the most canonical — Willem Frederik Hermans, Gerard Reve, and Jan Wolkers — picked up the thread of the Tachtigers and devoted themselves to the cat. Almost every well-known Dutch author wrote a cat story or autobiographical non-fiction about or prominently featuring cats. The ultimate ode to the cat, indeed the “standard work” on the species, and a literary masterpiece, Rudy Kousbroek’s De Aaibaarheidsfactor (The Pettability Factor, 1969), contained a ranking system of some of the big hitters in the animal kingdom based on how willing they are to be petted, which featured in every new edition, including the audiobook.61 The Pettability Factor, published (complete with a soft, “pettable” cover) to immediate acclaim, described a “classification system” distinguishing animals that are untouchable because of their nature (piranhas), their substance (jellyfish), their poor understanding of the phenomenon (rodents) or poor appreciation of it (horses and dogs). There is only one animal that adores being petted and that is the cat, “the apotheosis in the evolution of pettability”.62 This classification, unsurprisingly, also reflects the fact that the cat was by far the most popular animal amongst the intellectual elite including the authors of the day. This counter-cultural preference resonated with a wider audience and found a fertile ground in a society in which the 1960s student movement had left a particularly great mark.63

De Poezenkrant [The Cat Newspaper], an example of alternative media that has been published at irregular intervals since the 1970s, also fits within this trend. Initially stemming from an experiment by graphic artist Piet Schreuders, in which a “newspaper” was launched that was designed as if cats had been in charge of the layout. De Poezenkrant, this newspaper produced by cats for cats (the address label features both the names of the cat and its owner), quickly became into a cult hit. The paper, which still exists, has no editorial policy or indeed no editorial team at all, has a partially user-created format, and shows ugly cats on the cover so as to actively discourage people from buying the newspaper.64 The impact of this continuous appropriation of the cat by alternative writers and authors is reflected in the political orientation of the cat owner, who generally lean towards the political left.65 Recent large-scale research into pet ownership in combination with voting behaviour shows that more left-wing voters own cats and that those identifying as politically right-wing are more likely to keep dogs.66 Other studies confirm this.67 Cats — contrary, stubborn, and unconforming — are almost universally associated with a tendency to disrupt, confound, and even revolt, and in the Dutch cultural imagination even more so.68

Conclusion

One hundred and fifty years after laws prohibited the chaining up of cats on the grounds that it was antithetical to their nature, that nature has once again become the focus of an international debate on the damage free-roaming cats do to their natural surroundings and the necessity of keeping them indoors. Then as now, the language used to describe the problem is anthropomorphic and accusatorial: cats used to be evil, wicked, and feminine; now they are vicious and intent on “taking over the world”. Evidently, we continue to struggle with the identity of the cat and our relationship with one of our favourite companion species.

Calls for legal action to prohibit cats from roaming freely, indiscriminately killing and eating birds and other wildlife, can also be heard in the Netherlands, particularly from the Huiskat Thuiskat foundation. Dutch opponents of the free-roaming cat face enormous opposition, however, since cats have been firmly embedded within Dutch society since the late nineteenth century, and the government has so far declined requests for a bill mandating that cats be kept indoors. If anywhere, the cat seems to have found a safe haven in the Netherlands where their eccentricities and rougher edges have consistently been cultivated and are at the very heart of the cat’s, and often also their owner’s, identity.

The ubiquitous Dutch pet cat is the ordinary house cat — not a pedigree cat — with a hint of the avantgarde and leftist politics. The key moment in the identity formation of the Dutch cat was the nineteenth century, an era characterized by the emergence of a profound affinity towards cats. From an outcast with a few wealthy ladies as its sole ally, via idiosyncratic nobles, romantics, and bourgeois families, the cat became the beloved and subversive muse of artists, writers, and other creatives. It was the cat of the countercultural movements — mainly the movement of the Tachtigers, and other free-thinkers — as well as people involved in political emancipatory movements, that persisted.

Although the twentieth century witnessed a more conventional embrace of feline representation and involvement, the avantgarde–socialist cat never went away, which is evident in literature, such as in the acclaimed and influential publications of De Poezenkrant and De Aaibaarheidsfactor, and in the voting behaviour of cat owners, which is predominantly (to a statistically significant degree) left-wing. While in the United Kingdom, the aesthetic appearance of cats garners greater attention, and in the French context the historically-rooted sexual connotations still take precedence, the Dutch perspective highlights the cat’s intrinsic autonomy. This autonomy, epitomized by the cat’s ability or agency to accept nourishment and affection from humans while at the same time retaining independence, is the fundamental attribute that resonates within the Dutch cultural context. Precisely this fundamental attribute of the cat would be impacted by rules imposing restrictions on their ability to roam free, making the implementation of such regulations unlikely in the foreseeable future.

Notes

-

The arguments in this article are based on research previously undertaken by one of the authors and published in Dutch: Ronnes and Van de Ven, “Van dakaas tot schootpoes”; Ronnes, “De subversieve huiskat”; and Ronnes “De anti-hond”.

-

See e.g. Loss et al., “Free-Ranging Domestic Cats”; Loss et al., “Review and Synthesis”; Trouwborst and Somsen, “Domestic Cats”; Marra and Santella, Cat Wars; Tucker, Lion in the Living Room.

-

See Kete, The Beast in the Boudoir, 115, 123–24, 131–33; Ritvo, The Animal Estate; Grier, Pets in America, 167–68.

-

Ronnes, “De subversieve huiskat”.

-

Aerts, “Felix als huisdier of ondier?”, 491–92,

-

Molle, “Inleiding”, 469; Prak, Dutch Republic, 250–61.

-

See for instance Jacob, “Walking the Terrain of History”.

-

See Israel, The Dutch Republic, 1019–66.

-

See Huygens, Trijntje Cornelis, act 3, scene 1; Bekker, De betoverde weereld; Ronnes and Van de Ven, “Van dakhaas tot schootpoes”, 121.

-

Tysens, Apollo’s marsdrager, 3:135.

-

Wolff and Deken, Abraham Blankaart, 10, 198.

-

Francq van Berkhey, Natuurlyke historie, 3:80.

-

Buffon, Histoire naturelle, 6:3–55.

-

Simpson, Book of the Cat, 3, 12–13; Freund and Yonan, “Cats”.

-

See Trompert-van Bavel, Belle van Zuylen en Haar Honden.

-

See, for instance, Isabelle de Charrière, letter to her brother Ditie van Tuyll, 7 Dec. 1769, Correspondence, https://charriere.huygens.knaw.nl/edition/entry/2070.

-

Rogers, The Cat and the Human Imagination, 86–88.

-

Charrière, Lettres de Mistriss Henley, 13–16.

-

Rogers, The Cat and the Human Imagination, 33.

-

See Carolien Naaktgeboren-Bos, “Aert Schouman”, Guusje & Gio (blog) 2 August 2017, https://caroliennaaktgeborenbos.nl/?p=1582.

-

Alewijn, “De roode kat van den Heer Abbing vertelt haar wedervaren aan eenige andere katten”, Amsterdam City Archives, Crommelin Family Archives, inv. no. 489.

-

Davids, “Aristocraten en juristen”, 193–94; Kluveld, Reis door de hel, 41.

-

“Het Haagsche honden- en katten-asyl”, Nieuwe Tilburgsche Courant, 27 October 1895. http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010154860:mpeg21:a0005.

-

“Verstikking van dieren”, Algemeen Handelsblad, 10 April 1896. https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010126527:mpeg21:p004.

-

Ronnes and van de Ven, “Van dakhaas tot schootpoes”, 126; “Wenken en vragen”, Algemeen Handelsblad 4 Sept. 1885, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010143464:mpeg21:p002.

-

Hillenius, “Mens, dier en ethiek”, 133–34; Everse, “Het dier als proefdier”, 91–92.

-

Cliteur, Darwin, dier en recht, 40–46, 60–72; Verdonk, Het dierloze gerecht, 68–77.

-

Koch, Abraham Kuyper; Wintle, Economic and Social History, 312–23.

-

Domela Nieuwenhuis, Familicorrespondentie, 439–40.

-

“Dierenbescherming en Menschenmishandeling,” Recht voor allen, 26 April 1884, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=MMIISG05:000089917:mpeg21:p006.

-

“Een toevluchtsoord voor onbeheerde dieren,” Algemeen Handelsblad, 23 May 1878, https://www.delpher.nl/nl/kranten/view?coll=ddd&identifier=ddd:010102443:mpeg21:p005.

-

Kluveld, Reis door de hel, 29.

-

Romein, Op het breukvlak van twee eeuwen; Kluveld, Reis door de hel, 17; De Rooy, “Een hevig gewarrel”; Koolmees, “Het doden van dieren in Nederland”; Huisman and Te Velde. “Op zoek naar nieuwe vormen”.

-

Kluveld, Reis door de hel, 44–45, 48–49.

-

“Binnenland”, De Tijd, 4 March 1875. https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010263904:mpeg21:p002.

-

“Honden en politie”, De Tijd, 4 July 1879, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010265356:mpeg21:p003.

-

Davids, Dieren en Nederlanders, 139.

-

Kraaij, Henriette Ronner-Knip, 84.

-

Greer, Obstacle Race, 86.

-

Kraaij, Henriette Ronner-Knip, 106–26.

-

Ronnes and Van de Ven, “Van dakhaas tot schootpoes”, 127.

-

Horst, Spinnende poezen, 10.

-

Kraaij, Henriette Ronner-Knip, 78–84, 106–126.

-

Morris, Cats in Art, 81–102; Rubin, Impressionist Cats and Dogs.

-

Fields, Le Chat Noir, 6–37; Rubin, 13–22.

-

Black, “Baudelaire as Dandy”, 190.

-

Tholen, letter to Witsen, 24 June 1890, Volledige briefwisseling, https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/wits009brie01_01//wits009brie01_01_0304.php.

-

Witsen, letter to Willem “Pam” Witsen Jr., 10 February 1903, Volledige briefwisseling, https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/wits009brie01_01/wits009brie01_01_1184.php.

-

Dekker, Katten, 11–14.

-

Looy, “De dood van mijn poes.”

-

Eeden, Dagboek, 3.

-

Eeden, Dagboek, 104, 225, 1186, 1329.

-

Eeden, Dromenboek, 385.

-

Endt, Het festijn van Tachtig, 29; Halsema, Vrienden & visioenen, 43–44.

-

Gorter, Mei, Een gedicht, 50; Kloos, Nieuwere literatuur-geschiedenis, 82; Deyssel and Verwey, Briefwisseling, 45.

-

Haan, Brieven.

-

Kloos and Verwey, De onbevoegdheid, 6.

-

Kloos, Nieuwere literatuur-geschiedenis, 182; Van Deyssel, “Tegen de hitte”, 22.

-

Couperus, "Imperia", 162–63.

-

Saris and Van der Windt, “De opkomst”; Deen, “Tegen het palingtrekken”.

-

Kousbroek, Aaibaarheidsfactor; Jacobs, “Poezelogie”, 81; van Eeuwen, “Hekel aan een huis vol herrie”; Van den Boogaard, “De man en zijn poes”.

-

Kousbroek, Aaibaarheidsfactor, 18–24.

-

Kennedy, Building New Babylon.

-

Schreuders, Het Grote Boek van De Poezenkrant, 15.

-

Ronnes and Van de Ven, “Van dakhaas tot schootpoes”, 136.

-

Figures from Intomart. Thanks to Tom van Dijk and Pieter van Eeden. The same has been argued for the United States (Ivanski et al., “Pets and Politics”), although other research contradicts this: Coren, “Dog Ownership”.

-

According to one study, cat owners in the Netherlands mainly live in the city and dog owners in rural areas, which is congruent with predominantly left and right voting behaviour. The north of the country, traditionally a socialist stronghold, has the highest cat density (Feiten & Cijfers, 10).

-

In the UK no correlation has been found between cat ownership and electoral geography. The purebred cat persevered, yet it is the dog that is the most popular pet. See Murray et al., “Number and Ownership” and “Most Popular Pets in the UK”, Petplan 2018, https://www.petplan.co.uk/pet-information/blog/most-popular-pets/.

Works Cited

Aerts, Erik. “Felix als huisdier of ondier? De relatie tussen mens en kat in middeleeuwen en nieuwe tijd.” Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis 125, no. 4 (2012): 488–503. https://doi.org/10.5117/TVGESCH2012.4.AERT.

Bekker, Balthasar. De betoverde weereld. Amsterdam: Daniel van den Dalen, 1691.

Black, Lynette C. “Baudelaire as Dandy: Artifice and the Search for Beauty.” Nineteenth-Century French Studies 17, no. 1/2 (1988): 186–95.

Boogaard, Raymond van den. “De man en zijn poes.” NRC 3 October 2015. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2015/10/03/de-man-en-zijn-poes-1539193-a1032162

Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de. Histoire naturelle, générale et particuliére. Avec la description du Cabinet du roi. Vol. 6. Paris: Impr. royal, 1766. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k10672421.

Charrière, Isabelle de. La Correspondence d’Isabelle de Charrière / De briefwisseling van Belle van Zuylen. Edited by Suzan van Dijk and Madeleine van Strien-Chardonneau. Amsterdam: Huygens Instituut, 2012–.https://charriere.huygens.knaw.nl/.

Charrière, Isabelle de. Lettres de Mistriss Henley, publiées par son amie. Edited by Joan Hinde Stewart and Philip Stewart. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1993.

Cliteur, Paul. Darwin, dier en recht. Amsterdam: Boom, 2001.

Coren, Stanley. “Dog Ownership Predicts Voting Behavior — Cats Do Not.” Psychology Today, 27 August 2019. https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/canine-corner/201908/dog-ownership-predicts-voting-behavior-cats-do-not.

Couperus, Louis. “Imperia.” In Korte arabesken, edited by H. T. M. van Vliet, Oege Dijkstra, Marijke Stapert-Eggen, and Karel Reijnders, 162–71. Utrecht: L. J. Veen, 1990 [1911]. https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/coup002kort02_01/coup002kort02_01_0017.php.

Davids, Karel. “Aristocraten en juristen, financiers en feministen. Het beschavingsoffensief van de dierenbeschermers in Nederland voor de Eerste Wereldoorlog.” Volkskundig Bulletin 13, no. 2 (1987): 193–94.

Davids, Karel. Dieren en Nederlanders: Zeven eeuwen lief en leed. Utrecht: Matrijs, 1989.

Dekker, Tessel. Katten: Schetsen en foto’s van George Hendrik Breitner. Amsterdam: Panchaud, 2017.

Deen, Femke. “Tegen het palingtrekken en katknuppelen.” Het historisch nieuwsblad, 3 July 2012. https://www.historischnieuwsblad.nl/tegen-het-palingtrekken-en-katknuppelen/.

Deyssel, Lodewijk van. “Tegen de hitte en den schrijfkramp in. Papieren van Levensbeheer uit de zomer van 1891.” Edited by Harry G.M. Prick. Maatstaf 28, no. 8/9 (1980): 1–26.

Deyssel, Lodewijk van, and Albert Verwey. De briefwisseling tussen Lodewijk van Deyssel en Albert Verwey. Edited by Harry G.M. Prick. 3 vols. The Hague: Nederlands Letterkundig Museum en Documentatiecentrum, 1981–1986.

Domela Nieuwenhuis, Ferdinand. “En al beschouwen alle broeders mij als den verloren broeder”: De familiecorrespondentie van en over Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis, edited by Bert Altena and Rudolf de Jong. Amsterdam: Stichting Beheer IISG, 1997.

Eeden, Frederik van. Dagboek, 1878–1923. Edited by H.W. van Tricht. Culemborg: Tjeenk Willink-Noorduyn, 1971.

Eeden, Frederik van. Dromenboek. Edited by Dick Schlüter. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 1979.

Endt, Enno. Het festijn van Tachtig: De vervulling van heel groote dingen scheen nabij. Amsterdam: Nijgh & van Ditmar, 1990.

Eeuwen, Marion van. “Hekel aan een huis vol herrie.” NRC, 20 January 2000. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2000/01/20/hekel-aan-een-huis-vol-herrie-7478983-a79242.

Everse, J. W. R. “Het dier als proefdier.” In Relaties tussen mens, dier en maatschappij, edited by A. Verweij, 91–104. Wageningen: Centrum voor Landbouwpublikaties en Landbouwdocumentatie, 1973.

Feiten & Cijfers Gezelschapsdierensector 2015. ’s-Hertogenbosch: HAS Hogeschool; Utrecht: Universiteit Utrecht, 2015. https://edepot.wur.nl/361828.

Fields, Armond. Le Chat Noir: A Montmartre Cabaret and Its Artists in the Turn-of-the-Century in Paris. Santa Barbara, CA: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1993.

Francq van Berkhey, Johannes le. Natuurlyke historie voor kinderen. 3 vols. Leiden: Frans de Does, 1781. https://books.google.com/books?id=WxwOAAAAQAAJ.

Freund, Amy, and Michael Yonan. “Cats: The Soft Underbelly of the Enlightenment.” Journal18 no. 7 (2019). https://www.journal18.org/3778.

Gorter, Herman. Mei, Een gedicht. Amsterdam: W. Versluys, 1889.

Greer, Germaine. The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work. New York: Tauris Parke, 2001.

Grier, Katherine C. Pets in America: A History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Haan, Jacob Israël de. Brieven van en aan Jacob Israël de Haan 1899–1908. Edited by Rob Delvigne and Leo Ross. DNBL: Digitale bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse letteren, 2018. https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/haan008brie02_01/index.php.

Halsema, Dick F. van. Vrienden & Visioenen. Een biografie van Tachtig. Groningen: Historische Uitgeverij, 2010.

Hillenius, D. “Mens, dier en ethiek.” In Relaties tussen mens, dier en maatschappij, edited by A. Verweij, 124–137. Wageningen: Centrum voor Landbouwpublikaties en Landbouwdocumentatie, 1973.

Horst, Han van der. Spinnende poezen en speelse katjes: Het werk van Henriëtte Ronner-Knip (1821–1909). Schiedam: Scriptum, 2015.

Huisman, Frank, and Henk te Velde “Op zoek naar nieuwe vormen in wetenschap en politiek. De ‘medische’ kleine geloven.” De Negentiende Eeuw 25, no. 3 (2001): 129–36. https://demodernetijd.nl/wp-content/uploads/DNE-2001-3a-Huisman-Velde.pdf

Huygens, Constantijn. Trijntje Cornelis. Een volkse komedie uit de Gouden Eeuw. Edited by Harrie M. Hermkens and Paul Verhuyck. Amsterdam: Prometheus / Bert Bakker, 1997. https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/huyg001trij01_01/index.php.

Ivanski, Chantelle, Ronda F. Lo, and Raymond A. Mar. “Pets and Politics: Do Liberals and Conservatives Differ in Their Preferences for Cats Versus Dogs?” Collabra: Psychology 4, January 2021. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.28391.

Israel, Jonathan. The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

Jacob, Margaret. C. “Walking the Terrain of History with a Faulty Map.” BMGN — Low Countries Historical Review 130, no. 3 (2015): 72–78. https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.10104.

Jacobs, Herman. “Poezelogie: Rudy Kousbroek.” Knack Magazine, 18 March 2009.

Kennedy, James Carleton. “Building New Babylon: Cultural Change in the Netherlands During the 1960s.” PhD diss., University of Iowa, 1995.

Kete, Kathleen. The Beast in the Boudoir: Petkeeping in Nineteenth-Century Paris. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Kloos, Willem. Nieuwere literatuur-geschiedenis. Veertien jaar literatuur-geschiedenis, 1880–1893. Amsterdam: S.L. van Looy, 1925.

Kloos, Willem, and Albert Verwey. De onbevoegdheid der Hollandsche literaire kritiek. Amsterdam: W. Versluys, 1980.

Kluveld, Amanda. Reis door de hel der onschuldigen. De expressieve politiek van de Nederlandse anti-vivisectionisten, 1890–1940. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2000.

Koch, Jeroen. Abraham Kuyper: Een Biografie. Amsterdam: Boom, 2011.

Koolmees, Peter. “Het doden van dieren in Nederland, 1860–1940: Een onbehaaglijk onderdeel van de mens–dierrelatie.” De Moderne Tijd 2, no. 3–4 (2018): 326–47. https://doi.org/10.5117/DMT2018.3-4.008.KOOL.

Kousbroek, Rudy. De aaibaarheidsfactor. Amsterdam: de Harmonie, 1969.

Kraaij, Harry J. Henriette Ronner-Knip, 1821–1909. Een virtuoos dierschilderes. Schiedam: Scriptum Art, 1998.

Looy, Jac van. “De dood van mijn poes.” De Nieuwe Gids 4, no. 2 (1889): 49–74.

Loss, Scott R., Tom Will, and Peter P. Marra. “The Impact of Free-Ranging Domestic Cats on Wildlife of the United States.” Nature Communications 4 (2013): 1396. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2380.

Loss, Scott R., Brooke Boughton, Samantha M. Cady, David W. Londe, Caleb McKinney, Timothy J. O’Connell, Georgia J. Riggs, and Ellen P. Robertson. “Review and Synthesis of the Global Literature on Domestic Cat Impacts on Wildlife.” Journal of Animal Ecology 91, no. 7 (2022): 1361–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13745.

Marra, Peter P., and Chris Santella. Cat Wars: The Devastating Consequences of a Cuddly Killer. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Molle, Leen van. “Inleiding. Een geschiedenis van mensen en (andere) dieren.” Tijdschrift voor geschiedenis 125, no. 4 (2012): 464–75. https://doi.org/10.5117/TVGESCH2012.4.MOLL.

Moore, Arden. The Cat Behavior Answer Book: Practical Insights & Proven Solutions for Your Feline Questions. North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing, 2007.

Morris, Desmond. Cats in Art. London: Reaktion Books, 2017.

Murray, Jane K., William J. Browne, Maggie A. Roberts, Alex Whitmarsh, and Timothy J. Gruffydd-Jones. “Number and Ownership Profiles of Cats and Dogs in the UK.” The Veterinary Record 166, no. 6 (2010): 163–68. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.b4712.

Prak, Maarten. The Dutch Republic in the Seventeenth Century: The Golden Age. Translated by Diane Webb. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Ritvo, Harriet. The Animal Estate. The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Rogers, Katharine M. The Cat and the Human Imagination: Feline Images from Bast to Garfield. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Romein, Jan. Op het breukvlak van twee eeuwen. Leiden: Querido, 1967.

Ronnes, Hanneke. “De anti-hond. Poezen en edellieden.” Virtus: Journal of Nobility Studies no. 29 (2022): 84–96. https://doi.org/10.21827/virtus.29.84-96.

Ronnes, Hanneke. “De subversieve huiskat. Kunstenaars en poezen in Nederland, 1885–1910.” De Moderne Tijd 2, nos. 3–4 (2018): 248–66. https://demodernetijd.nl/wp-content/uploads/DMT-2018-34d-Ronnes.pdf.

Ronnes, Hanneke, and Victor van de Ven. “Van dakhaas tot schootpoes. De opkomst van de kat als huisdier in Nederland in de negentiende eeuw.” De Negentiende Eeuw 37, no. 2 (2013): 116–36. https://demodernetijd.nl/wp-content/uploads/DNE-2013-2b-Ronnes-Ven.pdf.

Rooy, Piet de. “Een hevig gewarrel. Humanitair idealisme en socialisme in Nederland rond de eeuwwisseling.” BMGN — Low Countries Historical Review 106, no. 4 (1991): 625–40. https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.3440.

Rubin, James Henry. Impressionist Cats and Dogs: Pets in Paintings of Modern Life. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Saris, Frank, and Henny van der Windt. “De opkomst van de natuurbeschermingsbeweging tussen particulier en politiek (1880–1940).” Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis (2019): 21–31.

Schreuders, Piet. Het Grote boek van De Poezenkrant. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Rubinstein, 2004.

Simpson, Frances. The Book of the Cat. London: Cassell, 1903.

Trompert-van Bavel, Trix. Belle van Zuylen en haar honden. Groenlo: self-pub., 2014.

Trouwborst, Arie, and Han Somsen, “Domestic Cats (Felis catus) and European Nature Conservation Law — Applying the EU Birds and Habitats Directives to a Significant but Neglected Threat to Wildlife.” Journal of Environmental Law 32, no. 3 (2020): 391–415. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqz035.

Tucker, Abigail. The Lion in the Living Room: How House Cats Tamed Us and Took Over the World. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

Tysens, Gysbert. Apollo’s marsdrager, veilende allerhande scherpzinnige en vermakelyke snel, punt, schimp, en mengel-digten. Met aardige Printjes verçiert. Vol 3. Amsterdam: Henderik Bosch, 1728.

Verdonk, Dirk-Jan. Het dierloze gerecht: Een vegetarische geschiedenis van Nederland. Amsterdam: Boom, 2009.

Wintle, Michael. An Economic and Social History of the Netherlands, 1800–1920: Demographic, Economic and Social Transition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Witsen, Willem. Volledige briefwisseling, 1877–1923. Edited by Leo Jansen, Odilia Vermeulen, Irene de Groot, and Ester Wouthuysen. Groningen: Noordhoff, 1971. https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/wits009brie01_01/index.php.

Wolff, Betje, and Aagje Deken. Brieven van Abraham Blankaart. Vol. 1. The Hague: Isaac van Cleef, 1787.