Facing Extinction:

Animal Death Masks in the Post-Mortem Museum Representation of Gorillas

DOI: http://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.10933

Keywords: museums, death masks, gorilla, conservation, preservation, heritage, taxidermy

Email: burkeve@tcd.ie

Humanimalia 13.1 (Fall 2022)

Abstract

When we consider the preservation of the animal body in natural history displays, we primarily think of techniques such as taxidermy or the mounting of a skeletal anatomy. Animal death masks are, by contrast, almost completely unstudied. Although casting has been predominantly understood as a technique for preserving the human face, nonhumans have also had their faces captured by the casting of a death mask, and the resultant plaster used for a variety of purposes, from the creation of an accurate taxidermy mount, to featuring as a display object in its own right. “Animal Death Masks” examines three case studies in which death masks play an integral role, all of which feature male gorillas kept in city zoos who grew to be local celebrities and were preserved for display in their regional museum, and each of whom had a cast taken of their face after death. This article argues that animal death masks materialize the distorted boundaries present in museum primate narratives: between indexical representations and artistic portraits, endangered animals and celebrity, conservation and preservation.

One frosty morning in New York, shortly after Christmas, I had a striking encounter with a male silverback gorilla. This meeting did not take place on the city’s streets, of course, but in a darkened room of the Akeley Hall of African Mammals, in one of the western world’s most iconic museums: the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). Although hundreds of thousands of visitors have encountered the “Giant of Karisimbi” since his installation in 1936, one encounter — the first — remains the best known. The story goes like this. The institution’s taxidermist, Carl Akeley, ventured out on an expedition to what was then the Belgian Congo to collect specimens for mounting in the museum’s galleries. Encountering “a magnificent creature with the face of an amiable giant,” Akeley shot and killed the animal.1 The good-natured simian face was “molded forever from the death mask cast from his corpse,” while the body was carefully taxidermied for exhibition.2 The experience left such an impression on Akeley that he began to process the conflict between the kind of preservation undertaken in the museum diorama and the conservation of animal populations in their own habitats, eventually becoming “motivated to convince the Belgian government to make [the Kivu mountains] the first African national park to ensure sanctuary for the gorilla.”3 Much has been written about Akeley’s transformative experience with the “Giant of Karisimbi”,4 and yet little attention has been paid to a specific aspect of the transformation from living gorilla into taxidermy mount: the creation of an animal death mask. This article hopes to redress this balance, bringing new attention to the roles that gorilla death masks play in the post-mortem representation of primates in contemporary museum narratives.

Human death masks — a wax or plaster cast posthumously taken of a person’s face — were created for a number of reasons, including as reference material for a portrait, as a memorial imbued with relic-like power through contact with the absent body, and out of the desire to preserve a supposedly objective likeness of an important person. Yet as the above incident illustrates, humans are not the only animals from which funerary plasters have been produced. Nonhumans have also had their faces preserved by the casting process, and the resultant masks have been used for a variety of purposes, from the basis for an accurate taxidermy mount to functioning as display objects in their own right. As with humans, the best-known nonhuman plaster casts are usually of famous individuals, endangered megafauna who become anthropomorphized ambassadors for their species.

When “representing animals” becomes crucial to “ways of thinking about, and ultimately interacting with, animals themselves,”5 the menageries on display in museums become a vital source of analysis for the mediation of the other-than-human. Although the taxidermy and skeletal anatomies on display in natural history museums have been extensively studied, literature on the role of death masks is considerably less extensive and little research about animal death masks has been undertaken.6 The material difference of death masks from these post-mortem representations reveals additional depth to stories about nonhuman animals. This article argues that animal death masks materialize the distorted boundaries present in the post-mortem representation of primates in natural history museum narratives: between indexical representations and artistic portraits, endangered animals and celebrity, conservation and preservation.

From here, I will explore three case studies in which death masks play an integral role in an animal’s institutional afterlife. All three involve death masks taken of male gorillas kept in city zoos who grew to be local celebrities and were preserved for display in their regional museum. While these cases highlight the diversity of preservation techniques and narratives used to represent gorillas in western cultural institutions, my focus is rather on how their death masks function in a contemporary display context. First, a behind-the-scenes visit to Berlin’s Museum für Naturkunde takes us to the institution’s renowned taxidermy workshop, where Berlin Zoo’s first gorilla, Bobby, was taxidermied. This case study questions the indexical nature of the funerary plaster and the role of the death mask as a post-mortem portrait. Next, we consider the institutional afterlives of Bristol Zoo’s famous gorilla, Alfred. After his death, both the zoo and Alfred’s fans were keen to memorialize the locally famous western lowland gorilla. A death mask was taken and his body was mounted, capturing Alfred’s well-known features, while both letters and zoo ephemera in Bristol Museum’s archives and the institution’s exhibition emphasized his personality. This perspective shift from animal to celebrity is most evident in the display of his death mask, which obscures the other-than-human nature of the gorilla. Finally, we encounter the story of Milwaukee captive Samson, whose unusual post-mortem preservation figures a twenty-first century evolution of Akeley’s anxieties about the conflict between wildlife conservation and museum forms of preservation, and whose death mask’s relic-like connection to the original animal serves the purpose of authenticating other post-mortem representations. While these gorillas’ institutional afterlives share commonalities, examining the role their death masks play reveals significant variation in the construction of museum narratives about endangered primates. Before we engage with the role of the cast in the display narratives of these three case studies, however, we must consider the death mask in the cultural context of primate exhibition.

Death Masks in the Context of Primate Exhibition

Cultural historian Ole Marius Hylland’s suggestion that the act of making a death mask can be interpreted as “a stubborn, existential act of defiance, an attempt to freeze a certain point in time” envisions the face casts as a rear-guard action against loss, an effort to materialize some element of the individual for posterity.7 Plasters serve historically as “relics, general memento mori objects, practical tools for sculptors, objects of remembrance for dignitaries, study objects for medical sciences and objects of entertainment and exhibition.”8 The nonhuman death masks in this study often serve similar display purposes as the human ones, even if their historical contexts and subjects are radically different.

Taking a death mask was a complicated process, with formatori (the artisans who took the mould and made the cast) each having their own preferred techniques. Georg Kolbe, a renowned early-twentieth-century German sculptor, was also a master of the art of funerary plaster casting, using the masks as reference points for the busts he crafted. His description of creating the mould provides a sense of the processes involved:

The parts where hair is growing are painted over with a thin solution of modelling clay or with oil, so that the plaster may not adhere when it is poured over [the face.] The outline of the mask, the parts on the neck, behind the ears, and so on, are surrounded with the thinnest of damp paper […] a large bowl of plaster of the consistency of soup is ladled over the face a few millimetres in thickness; then a thread is drawn over the middle of the forehead, the bridge of the nose, the mouth and chin. A second bowl of more solid plaster is spread over the first layer like pulp (this is to provide a firm outer shell), and before it sets the thread is drawn away, dividing the whole into two halves. As soon as the outer layer has set hard, the halved mould is broken apart and carefully detached from the head; this is the most difficult step, for the mould enclosing the body was airtight. The halves thus detached are immediately fitted together again and clamped, the negative is cleaned and refilled with plaster. Roughness on the covering outer shell [is] carefully chipped away with mallet and chisel, and there we have the positive, the finished mask.9

This process is complicated by nonhuman bodies, which present different challenges to those of humans: the hair needs to be covered in oil to prevent the plaster from sticking on fur-covered mammals and feathered birds, while the positions of ears, beaks and snouts can make removing the mould without damage especially difficult. Animal death masks are usually taken of specimens as reference for an accurate taxidermy mount, but the funerary plasters taken of celebrity animals also intend to capture a known individual as much as a specimen. The formal similarities with human death masks often lead institutions to display them in contexts which anthropomorphize them and imbue the casts with anthropocentric meanings. For example, the death mask of Dolly the cloned sheep has been displayed in the National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh, which also displays artworks featuring such notables as Mary, Queen of Scots and philosopher David Hume, rather than with the taxidermy mounts in the natural history collection of the National Museum of Scotland.10 The science of cloning has commodified the original animal and transformed the copy — the clone — into an animal celebrity, while the copy of that copy — the death mask — is consequently exhibited amongst art, as a celebrity artefact.

In the case of animal death masks, gorilla plasters particularly highlight a number of intersections between specimen and celebrity, conservation and preservation, indexical representation and art. Apes, and gorillas specifically, were long considered to have been a demonstration of the ‘missing link’ between human and animal creation.11 Molecular biologists have proven our kinship with apes at a genetic level: we share 99 per cent of our DNA with apes.12 As Donna Haraway has noted, “monkeys and apes have a privileged relation to nature and culture for western people: simians occupy the border zones between those potent mythic poles.”13 Andrew Flack additionally links the popularity of simians to the physical characteristics they share with humans (“rounded outlines, hair, an often-vertical posture, flat faces with familiar expressions, and the ability to manipulate small objects”), but in particular connects the recognition of animal individuality to the way humans are trained to seek personhood by looking at the face.14 The power of forming an emotional connection through facial recognition has frequently been used in conservation purposes for the endangered gorilla.15 This simian similarity is further emphasized when it comes to celebrity zoo animals, which have often been anthropomorphized by media reportage, display narrative and zoo ephemera. Writing about Bristol Zoo, the institution in which Alfred the Gorilla lived in captivity between the years of 1930 and 1948, Flack argues that “the power of these animals to mobilize emotions at the heart of the human-animal, object-subject binaries remains today. Its practicality, however, has transformed in line with conservationist agendas.”16

As Noah Cincinnati has noted, this conservationist agenda was far from simple. In the early twentieth century, conservationists “framed the collection of threatened species as critical to preventing extinction,” yet vast numbers of gorillas were killed when resisting capture.17 Others were explicitly shot for post-mortem display, in line with the beliefs of naturalists such as William Hornaday of the New York Zoological Park (today the Bronx Zoo), who argued that the “highest function that any wild animal can serve, living and dead, is to go on exhibition, as a representative of its species, to be seen and studied by millions of serious-minded people.”18

The animal trade, zoos, and museums were all interconnected during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Western institutions benefited from their colonial connections and gorillas were traded as commodities across cultural institutions in order to be exhibited dead or alive.19 Colonial expansion “fuelled intense museological traffic in the late nineteenth century”,20 and overlapped with a drive to appeal to a mass audience that extended into the early twentieth century. The gorilla was uniquely suited to serve as both an icon of the west’s colonial power and as a crowd-pleaser. Early gorilla displays frequently fed into colonial narratives. Mounts were, for example, exhibited in an intimidating attack position so that “European museum-goers, thrilled or terrified, could soothe themselves with the thought that white hunters had overcome the fearsome monster, and with the knowledge that solid glass stood between themselves and it.”21 Other series showcased the primate’s physical similarity to humans as evidence of Darwinian evolution — for example, walking upright like man, or in ethnographic displays with other, supposedly less “evolved”, races.22 Zoo media in the early twentieth century, when the three gorillas chosen for case studies were held in captivity, further capitalized on these similarities by constructing anthropomorphized personalities to amplify an animal’s fame.

Animal celebrity is “now a basic mode of animal presentation for zoos, which employ so-called charismatic megafauna, or ‘flagship species’, to represent whole ecosystems and continents as ‘fundraising ambassadors.’”23 As Susan Nance has argued, “animal celebrities always need human mediators with the press and public, and who apply to a given animal’s behaviour a story about the animal’s awareness of his or her surroundings and motivations.”24 An unintended side effect of this celebrity status can be that when we celebrate a single individual, “we relegate the rest to a heightened obscurity.”25 In mid-twentieth century studies of wild populations by primatologists such as Dian Fossey and George Schaller, gorilla subjects were endowed with gendered pronouns, “rendering an animal no longer as an ‘it’ but rather as ‘she’ or ‘he’”.26 The act of naming, moreover, “offered the possibility of understanding individuals as not simply placeholders of animal behaviour but as subjective beings,” thereby effecting significant change in conservation policies.27

Human–simian similarities have nonetheless frequently concealed the historical commodification and endangerment of the species in their museum context, where displays foreground accuracy of representation, authenticity, and celebrity. The correlation between representations of the face, memorialization and animal personhood could be powerfully evoked by the death mask in museum narratives. Exhibiting the individual’s face can, for instance, figure as a memorial, a form of portraiture, a mirror to celebrity culture, but also as a specimen, or as a complex combination of all four. Yet in echoing the uses of human death masks, the narrative meanings present in contemporary displays of animal death masks, especially those who lived in captivity, can figure material evidence of the tensions present in representing gorillas in museum display.

“The Mona Lisa Smile of Bobby the Gorilla”

The introduction to my first case study comes by way of Ton Hermans, a general practitioner from the Netherlands who wrote a short article detailing his visit to the Masterpieces of Taxidermy gallery in the Museum für Naturkunde (MfN), Berlin. Hermans was particularly taken with “one of their masterpieces”:

Bobby, an enormous specimen of a gorilla, 1.72 meters high, and 266 kilos in body weight when he died. His position was very natural and the expression on his face touching. A sort of Mona Lisa smile caused me to wonder what was so special about this animal. Bobby was introduced in the Zoo of Berlin in 1928, as a young male, bought in Central Africa. In a short time, he became one of the most popular animals in the Zoo, the darling of the public and his keepers. He was intelligent and friendly, and never showed the unexpected episodes of bad temper, well-known and feared from gorillas. He developed into a real personality in both the Zoo and Berlin.28

On “a bad day in 1935,” Bobby took ill, and despite the best care of veterinarians, he passed away from what was later discovered to be appendicitis. Once he died, the MfN offered to “prolong his existence” by preparing his skin as a taxidermy mount. After a death mask was taken and casts were made of both hands and feet, the taxidermy mount of Bobby has been exhibited in the capital’s natural history museum ever since.29

Although Herman’s exhibition review offers us a concise introduction to Bobby and the kind of biographizing that frames “celebrity” zoo animals, it also relates a particular visual language: that Bobby looked “very natural”; that Herman had an emotional response to the “expression on his face” and a subtle paralleling of taxidermy with art in the reference to the portrait of the Mona Lisa.30 The dialogue between sculpture and specimen preservation can be traced back to the nineteenth-century trend for taxidermists to produce realistic, “lifelike” representations. The genre of realism — which intended to show nature as close to “reality” as possible — dominated taxidermy during the era in which Berlin’s gorilla was preserved.31

Death masks have been understood as highly accurate representations of the “real,” as they supposedly create an exact copy of the subject’s face. But analysing Bobby’s mask disrupts this sense of indexicality. The process of making the specimen look “real” was considered an art and had a particularly close relation to portraiture and sculpture, for which human and animal death masks alike were most frequently taken. According to late-nineteenth-century biologist Vernon L. Kellogg, taxidermy should simultaneously reveal “the peculiar characteristics of the animal species represented,” while possessing “the power of displaying the emotions and passions” and thus “appeal to the human senses just as a figure in marble or bronze may,” a sentiment which finds echoes in Herman’s response to the finished “masterpiece” of Bobby.32

Dermoplasty, a technique developed by German taxidermist Philipp Leopold Martin (1850–1885), replaced earlier “stuffed animal” approaches, with the taxidermist instead sculpting a model onto which the skin was carefully positioned. Martin’s approach to facial dermoplasty advanced taxidermic realism using the techniques of sculpture:

clay is injected towards the ears, then at the corners of the mouth towards the animal’s cheeks and face parts, whereupon, using one’s fingers or modelling tools, the intended physiognomy can easily be produced. For noses and lips, however, one must use firmer clay, which of course must be put in place with one’s fingers […]. The lips are sealed with temporary thread and this part is modelled from the outside, whereby, as the clay often stays soft for days, there is no need to hurry, and one can make improvements and adjustments as needed. — It will be clear that only in this way is it possible to achieve an animal’s correct physiognomy.33

An appearance of correct and natural physiognomy is aped through artistic intervention, which is consequently obscured through the act of naturalistic taxidermy. It is, however, exactly these texts and techniques that highlight the extent to which taxidermy and sculpture overlap.

The dermoplasty of Bobby is overtly represented as a sculpture-specimen hybrid in press coverage of the unveiling of his taxidermied body:

A large, light room behind the scenes of the Natural History Museum, half sculptor’s studio, half silent zoo. Centre stage is a something, draped in white dust sheets. The cover falls. Bobby the gorilla, just recently completed, sits lifelike before us. So true to nature, that one takes an involuntary step backwards because strong railings no longer separate us from this unearthly creature of the primeval forest, which was gazed upon for years in our zoo. For the first time in the history of animal preservation they have succeeded in preparing a gorilla perfectly. Even the dermoplasty sculptor, Karl Kaestner, Chief Taxidermist at the Natural History Museum, and Gerhard Schröder, are satisfied with their work. Bobby sits upright supported by his right hand, and his gaze appears, as in his lifetime, to glide past the masses of people around his cage.34

The “lifelike” sculpture, installed in a museum of natural history, is suggestive of the elevation of taxidermy to art and of a shift from representing Bobby solely as a specimen to serving as a portrait of an individual and as emblematic of the art of taxidermy.

A visit to the MfN’s world-renowned taxidermy workshop, down corridors lined with medals from preservation championships, provides valuable insight into the historic and contemporary production of animal death masks, as well as revealing their particular role for gorilla taxidermy. Robert Stein, one of the institution’s senior taxidermists, explained that animal death masks are usually taken as reference for the eventual taxidermy mount, with casts not uncommonly discarded after use. The Berlin workshop prefers the method of mixing clay and water and lightly coating the fur before plaster is applied, isolating the fibres from the casting solution and washing off easily to minimize fur loss on a soon-to-be taxidermied skin. Occasionally the face is subtly sculpted before a death mask is taken, with salt water solution used to plump up tissues and hold the eyes open, an intervention to make the animal look more ‘natural’.35 In the case of some species, such as gazelles, there is considered to be no need to cast a death mask from the individual body; instead, the taxidermist simply takes measurements and uses a reference mask already annexed within the museum’s vast stores. In contrast, the face and personality of a gorilla is considered highly individual; so much so that even when the deceased gorilla is not widely known to the public, the taxidermists of the Berlin workshop prefer to take a cast of both head and hands to enable a precise fit to the individual body.36

Although it is unusual for animal casts to be displayed as museum objects in their own right (with an exception made for displays about the taxidermic process, such as the MfN’s Masterpieces of Taxidermy gallery), plaster masks hang on the wall of the workshop, including a refined cast of Bobby’s face. Compared to other gorilla death masks which inevitably capture the unedited face of the animal as it was in death (such as that of Alfred discussed below), the plaster of Bobby is an incredibly detailed and recognisable portrait of the living animal. The connections with portraiture are reinforced by its display on the workshop wall, where it no longer functions as reference material but as an example of the workshop’s level of artistry. Stein reveals an unusual reason for the uncannily lifelike face: this is not the post-mortem plaster referenced by Hermans but is instead a cast taken from the animal’s face at the end of the dermoplasty process. The gorilla’s body had been soaking in a tank of paraffin preparation, which MfN taxidermist Ralf Bonke credits with the exceptional preservation of Bobby’s skin. The sculpted face was subsequently cast and gifted to multiple institutions as an example not just of gorilla anatomy but of successful preservation.

A side-by-side comparison of the two masks raises startling differences. The original cast was thought not to look “right”: the mouth was particularly pointed out as “wrong”, a value judgment which balanced the incorrect representation of the gorilla’s anatomy with the plaster’s poor aesthetic. The naturalistic expression, with closed eyes, sloped mouth and hair visibly trapped within the plaster may accurately represent the animal as he was in death and provide a sense of authentic physical proximity, but such an image could not function as a public portrait since it would disrupt the constructed character of the celebrity zoo animal. It is then the mask of the stately dermoplastic gorilla which ultimately functions as compelling evidence of how the artistry of taxidermy can make the dead look convincingly “lifelike”.

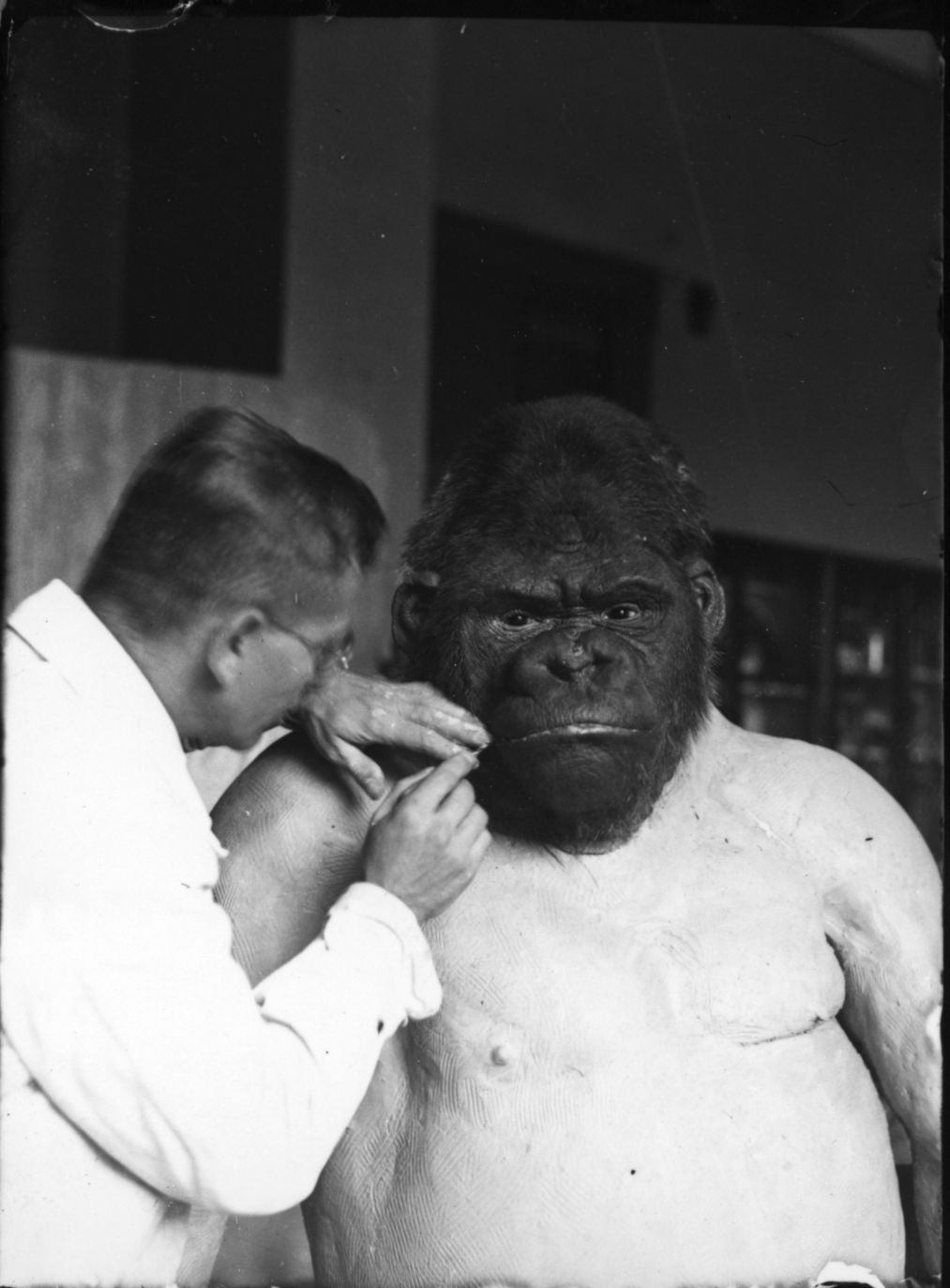

The photographic series previously displayed on the MfN’s webpage for the Masters of Taxidermy gallery reveals the fault lines between the artistic goal of realism and the extreme level of intervention this requires, underscoring how the post-mortem artefacts of Bobby relate to the tradition of art as much as to the tradition of the specimen.37 The “eye contact” of the first image reinforces how natural the mount looks, evoking a sense that this is a living animal gazing gravely into the viewer’s eyes, while the faces of the taxidermists are tellingly averted. Only after tearing our own eyes away from those of the gorilla does the wider picture come into focus, providing an uncanny realization that this face is being fixed back onto a sculpted body, fracturing the impression that the living animal is sitting for his portrait. The image in which the cast is taken from the taxidermy highlights how, despite being based on the biological body, the second death mask idealizes both the animal and the taxidermic art which can create a ‘lifelike’ face. The photos contradict the understanding that a nonhuman facial cast should serve as reference material for making taxidermy, representing instead how the plaster is taken from the taxidermy. This simultaneously imagines the animal as an idealized version — a hyper-nature which is more in accordance with expectations of what nature should ‘really’ look like — and as the apex of the taxidermic art through which this was achieved.

Figure 1: A comparison of the original death mask of Bobby the Gorilla, with the mask taken of his taxidermy, in the stores of Museum für Naturkunde.

Photograph by the author. Included by kind permission of Museum für Naturkunde staff.

Returning to the Masterpieces of Taxidermy gallery at the MfN, visitors are introduced to the uncanny dissonance between the hyper-reality of the taxidermy mount, and the revelation of the human intervention behind it. Unusually for a natural history museum, the focus of the exhibition is on the art behind animal preparation rather than on an exploration of the natural world. Visitors gather around Bobby’s mount, displayed as the product of such artistic mediation, while the surrounding exhibition underscores how this effect was created. An image from the photographic series is displayed on an exhibition board, showing the preparation of Bobby at a crucial moment of reconstruction. It is only when looking closer, however, that it becomes possible to discern that this is the moment that Bobby’s face is being reattached (see Figure 2). Close attention to Bobby’s preparation reveals that the post-mortem animal has a function beyond that of a specimen, literalizing the connection between dermoplasty and sculpture.

Figure 2: Photograph of the Präparatoren Karl Kaestner and Gerhard Schröder working on the dermoplasty of Bobby in 1936.

Reproduced with thanks from Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Historische Bild- u. Schriftgutsammlungen (MfN, HBSB) ZM B III 1404.

Figure 3:

Photograph of Kaestner carefully moulding Bobby’s face to the sculpted mount.

MfN, HBSB, ZM B III 1317.

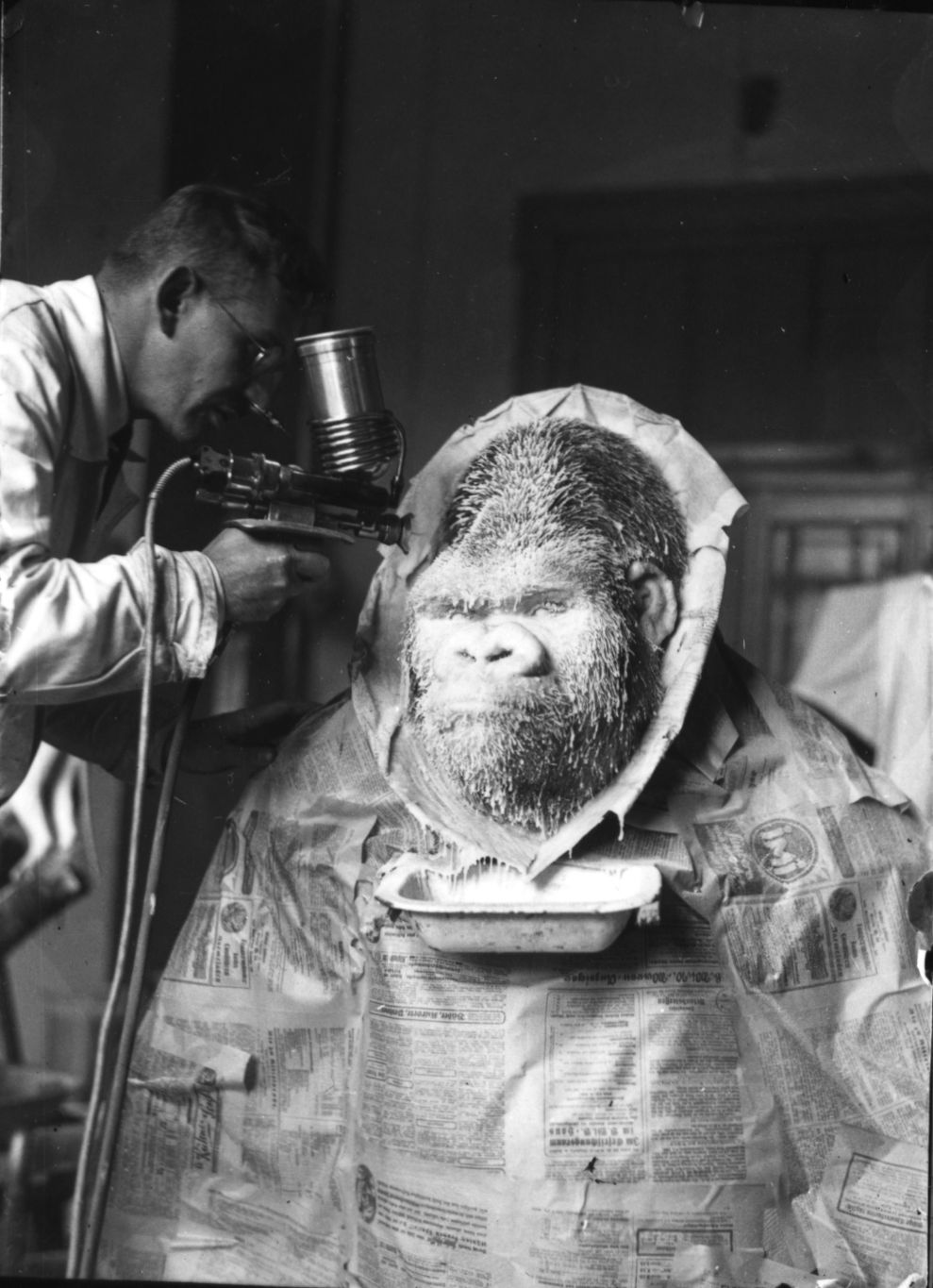

Figure 4:

Photograph of a new death mask being cast from the mounted dermoplasty of Bobby the Gorilla in 1936.

MfN, HBSB, ZM B III 1319.

The transformation of Bobby’s mask from reference material into art object can be fully realized not by visiting the mount’s final resting place, but rather by visiting the place where the gorilla spent most of his life. Artistic representations of Bobby abound at the Berlin Zoo, from an illustration of a stern-looking chiaroscuro gorilla with Bobby’s recognisable silhouette on the entrance sign, to more generalized gorilla imagery throughout the park. The best-known article of Bobby ephemera at the Berlin Zoo is German sculptor Fritz Behn’s stylized statue — sitting in the hunched position originally intended for the dermoplasty, and for which the MfN workshop still stores the plaster model used to plan the work in miniature. The statue guards the Primate House and continues to emphasize the transition from biological gorilla to art object. Within the monkey house itself, bronze sculptures of several species of primate hang spotlit on otherwise plain walls. A closer look provides an unexpected moment of recognition: the face of the gorilla is not just Bobby, but specifically the death mask cast from Bobby’s dermoplasty, while the other bronzes are cast from the corresponding death masks hanging in MfN’s taxidermy workshop. In this context, the death mask’s role as artwork becomes apparent, serving not as reference for a taxidermic portrait, but transformed into the “bronze” idealized by Kellogg. The imagery of the “Mona Lisa smile” identified by Hermans finds even stronger resonance here, for without contextualization, the death mask, which represents the apex of the art of taxidermy, passes as an art object, exhibited only feet away from actual sculptures. Just as Bobby’s unveiling allows the MfN to become “half sculptor’s studio, half silent zoo”, a critical analysis of the functions of the death mask reveals the object as a hybrid: an icon of the art of heritage preservation as well as a carefully crafted portrait of the individual face as it was brought ‘back to life’ by the taxidermy mount.

The Afterlives of Alfred

Samuel Alberti’s edited collection, The Afterlives of Animals (2011) lays out one of the founding principles of scholarship which examines museum animals. He explains that by examining an animal’s movement and meaning in life and death, and their presence in our institutional collections, we are “able to trace the shifting meanings (scientific, cultural, emotional) of singular animals and their remains.” These stories take us “from fields and rivers through zoos and menageries to museums”.38 As he points out, however, what we often discover is not the meaning of the animal, but the human-animal entanglement that the animal representations in such institutions iterate. For, even though these creatures are “nonhuman”, they are “instilled with many of our characteristics” and continue to be anthropomorphized post-mortem.39 In his landmark study of the Bristol Zoo (the erstwhile home of Alfred the Gorilla), Andrew Flack has pointed out that the duality of the object-subject perception of captive creatures is a fundamental principle of many human relationships with animals, and one which caused anxiety when humans recognized their own animal nature in the animals they observed — none more so than in the resemblance between humans and other primates.40 Flack goes so far as to single out visitor relationships with Alfred specifically as epitomizing “this intensifying sense of intimacy across the human-animal borderlands,” paralleling an “increasing concern for captive lives and a mounting anxiety about animal freedom and happiness.”41

It is the post-mortem element of this thread which I wish to take up, as Alfred’s death mask is a valuable case study through which to investigate the intersections between human and nonhuman, specimen and celebrity, and the use of these aspects after his death in institutional narratives about this famous gorilla. Encounters with the object afterlives of Alfred — specifically, the taxidermy mount in Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, the bronze bust of Alfred’s head which is displayed in Bristol Zoo’s Gorilla Island, and finally the death mask exhibited in the M Shed, a history museum focused on Bristol life — reveal how the tensions about which element of Alfred to focus on remain. One of the enduring elements of Alfred’s life and material afterlife has been his individual celebrity rather than his use as a zoological specimen.42 Alfred’s death mask adds vital framing to this interpretation for, according to art historian Jane Schuyler, in their human context, death masks were taken because of “the craving for fame.”43 While the taxidermy mount and bronze bust are partially contextualized with interpretation detailing the conservation of gorilla species, Alfred’s death mask is displayed similarly to the death masks of human dignitaries, and risks obscuring the sense of Alfred as an endangered animal.

Alfred’s anthropomorphized personality, bolstered through his proximity to humans, is the lens through which his life story is focused. The birth of the ‘Alfred’ identity is given as the date of his arrival at the zoo in 1930, rather than when he was actually born in the Belgian Congo, signifying how the gorilla’s wild identity has been replaced by his zoo “character”. Archival material indicates a continued entanglement of anthropomorphism and zoological milestones, with zoo literature and visitor testimony balancing delight at his stylish outfits — ranging from winter jumpers, hessian sacks and a handkerchief perched jauntily on his head — with his record as the oldest gorilla to survive in captivity.44 Alfred’s post-mortem life continued to centre his personality as much as zoological fact: although his bones and organs were sent to the anatomy department at Bristol University, these were never displayed. Perhaps (as with Samson, below) they were considered not representative of, or even detrimental to, the ‘character’ of Alfred constructed by zoo media.

As Flack argues, “personalities for zoo creatures were not only recognized but also intensively cultivated”, including a transformation “into honorary people”, which extends into representations of Alfred in the museum space.45 The taxidermy mount of Alfred is in the World Wildlife Gallery of Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, a darkened room displaying a historic collection of nineteenth and twentieth-century taxidermy. The mount’s face is markedly similar to the death mask, including the slightly lopsided nostrils, which suggests taxidermy company Rowland Ward made good use of the plaster. The placid expression, furthermore, sits well with the ambling gait requested by the museum’s curator, as this was how zoo visitors were accustomed to seeing him, disrupting the popular image of the animals as “terrifying apes”.46 Alfred is one of the only animals to stand alone — most are in clusters according to region or in dioramas, such as the Galapagos Giant Tortoise and a tiger hunted by King George V — and displayed without contextual habitat. The gallery interpretation indicates Alfred’s presence long before a glimpse of the mount is sighted. Numerous signs featuring cartoon renderings of the famous gorilla alert guests to his location, announcing “here I am” and situating the individual subject over the specimen object, providing an anthropomorphized and mediated sense of “who” that animal is.

Figure 5: An example of the cartoon signage pointing the way to Alfred’s taxidermy mount in Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

Photograph by the author.

Some vestiges from a recent intervention in the form of temporary exhibition Extinction Voices,47 which drew attention to endangered and extinct species within the gallery by obscuring specimens under funereal veils, remain and frame Alfred within a narrative of conservation concerns. This exhibition narrative, in which individual stories are appended to otherwise anonymous specimens, reaches its apex in the interpretation surrounding Alfred. Alfred has the most extensive signage of any animal in the gallery, but it is of a personal nature: he is overtly identified as an “icon for the city in life and death”, acknowledging his position as an important historical figure and as “more” than a wild animal. Despite the interpretation explicitly relating Alfred’s “place in Bristol’s cultural history”, the sign also argues that “Alfred’s legacy” is not just as a taxidermy object but also “a better understanding of gorillas” which has “contributed to attempts at preserving them in the wild”. However, the interpretation explicitly acknowledges that “Alfred represents many things to many people” and “can be viewed as an example of a species of an endangered mammal, an example of the taxidermist’s art or as an iconic Bristol legend,” a trifecta of endangered animal, specimen and celebrity which appears to inform display praxis surrounding the gorilla’s representation.48

Figure 6:

The taxidermy mount of Alfred the Gorilla in the World Wildlife Gallery in Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

© Bristol Culture.

The interconnected narrative between the endangered status of gorillas, the individuality of Alfred and an anthropomorphic focus on the face continues in another site strongly associated with the city’s famous western lowland gorilla. Alfred lived in captivity in Bristol Zoo for the majority of his life, and a bust of his head remains on display there to this day. The zoo’s living gorillas are connected with conservation concerns even before entering the zoo. An adult gorilla features, for instance, on signage and primate adoption schemes. The institution’s conservation programme is likewise illustrated with images of gorillas and they are advertised on the digital display screens used to entertain guests as they queue for tickets. The interpretation for Gorilla Island similarly creates a narrative that reinforces a conservationist message; while the interpretation contributes to the anthropomorphism of zoo captives by characterizing the animals as an ‘Extended Family’, correlating the gorillas’ dynamic with a nuclear human household, the signage also flags conservation issues and discusses nonhuman behaviours.

Figure 7: The bronze bust of Alfred the Gorilla as displayed in Bristol Zoo’s Gorilla Island.

Photograph by the author.

The institution’s development of the link between human visitors and the island’s other-than-human residents contextualizes the bust of Alfred, positioned unobtrusively by one of two main doors to the enclosure. The serious expression of the bronze face, gazing out from within a small enclave within the wall at adult eye height, is reminiscent of the memorial busts of well-known public figures. This impression is reinforced by the sober inscription on the base: “Alfred: Bristol Zoo’s Famous Lowland Gorilla. He arrived here on 5th September 1930 & died on 9th March 1948.” The final line continues to configure the object as memorial art, acknowledging its creation “by Roy Smith R.W.A. 1949”, an artist from Bristol’s Royal West of England Academy who completed it not long after Alfred’s demise. Although little information about the bust’s commissioning or its artist remains, the parallels between the bust and the death mask are strong. The object’s visual symmetry with the busts of human dignitaries silently anthropomorphizes Alfred; however, the bust is contextually connected with the conservation narratives developed in Gorilla Island’s interpretation.

Figure 8:

The death mask of Alfred displayed in the Bristol People Gallery of M Shed, Bristol.

Photograph by the author.

The death mask itself is displayed in Bristol’s M Shed, an institution which opened in 2011 and focuses on the city’s history and identity. Interestingly, information about Alfred is not included in the exhibition which deals with the zoo’s past. Unlike Bristol Zoo and Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, which feature Alfred-specific or gorilla-inspired branding and associated conservation narratives, the visitor’s first encounter with Alfred does not occur until the “Bristol Life” gallery on the second floor. Here the visitor is told about the theft (and eventual return) of Alfred’s body from the Bristol Museum in 1956.49 Alfred’s death mask is located in the “Bristol People” gallery in a prominent spot: the first object a visitor encounters if they turn to the right on entry, and part of a series of statues, busts and portraits which line the perimeter of the exhibition. The mask’s implicit connection to the traditions of portraiture, celebrity personhood and memorialization, and Alfred’s inclusion in the ‘Bristol People’ gallery, emphasizes Alfred’s closeness to humanity, while only minimal information about his species is provided.50

A close look at the mask reveals this to be the original copy (perhaps the sole one, as archival letters suggest the mould did not survive making the first “positive”).51 Biological material is embedded in the plaster, with the hairs that were trapped in the mould due to inefficient lubrication pulled free in the plaster of the first casting. In retaining these links to the organic body, the mask, like the taxidermy, functions as a hybrid object — simultaneously artistic impression and indexical copy, individual representative and Gorilla gorilla gorilla specimen. In doing so, his status as a member of an endangered species is obscured, extracted from his own environment in Central Africa and exhibited instead as a local celebrity in a Western cultural institution.

This obstruction is furthered by the object’s interpretation, which comes in the form of a tiny worn label, its cardboard starting to peel from the mount after years of repeated touch. Although the interpretation notes that “famous taxidermy company Rowland Ward preserved Alfred’s body which is still on display at Bristol Museum and Art Gallery,” the connection between the taxidermy and the cast’s use as reference material is left implicit. The label additionally signposts the city’s other iconic representation of Alfred, “a bronze bust […] still displayed at the entrance to the gorilla house at Bristol Zoo,” rather than any discussion of Alfred as an endangered animal. Only the object name, which classifies this item as a death mask, and half a sentence — “this plaster bust was made from his death mask” — discuss the item on display. It is relatively unusual for even human plasters to be exhibited as sole representations of their subjects; they were rarely taken with the intent to display, and tacit acknowledgement is made of this in the accompanying signage, which points to the location of preferable “portraits.” Although the letters from Rowland Ward state the urgent delivery of the death mask as soon as possible so that accurate work on the taxidermy mount could commence, the object’s own contextualization within the gallery suggests that the mask alone displays only one facet of the animal, signalling the necessity of visiting the other objects related to Alfred.

The gallery narrative serves to position the mask further along the spectrum to celebrity portrait than that of the museum or, due to its inclusion in the wider conservation narrative of Gorilla Island, than the bronze bust. In the extreme transition to “human,” signalled through the display of Alfred’s mask in the longer tradition of preserving human celebrity through funerary plasters, and its exhibition alongside other such objects, Alfred’s identity as a gorilla, rather than as an anthropomorphized celebrity, is ultimately obscured.

Remaining Samson

Death masks are imprints, material signs which, like a “dog’s footprints in the sand”, signal a body that is no longer there. As Marcia Pointon has argued, they “evoke absences and, in their fragmentary character, imply disembodiment”.

But imprints are also literally negatives. From them a positive can be made. We thus have a binary structure that permits, as we have remarked, not only one duplication but also multiplication.52

While Pointon is talking about the art of taking funerary plasters, her words could also be metaphorically applied to the attempt to increase species numbers in wildlife conservation. Our naive belief that if we can hold on to even a single member of a species, perhaps it will remain possible to multiply, to not succumb to the final loss of extinction is a hope which resonates throughout the current case study. As with Alfred and Bobby, the death mask is not the object most commonly associated with the memory of Samson, the silverback gorilla brought to Milwaukee, Wisconsin USA, in 1950. Yet, as with the two former primates, placing the death mask in context with other post-mortem representations of the animal throws light upon how these representations operate. An analysis of Samson’s material afterlife raises questions about the locus of an animal’s “essence”, highlights tensions between the conservation of animals in the wild versus museal forms of preservation and investigates which elements body-objects require to function as an emotive memorial.

Samson’s life story bears an uncanny resemblance to that of Bobby and Alfred: hailing from West Africa, Samson attracted significant crowds while in captivity, and he became a local celebrity.53 It was decided that his official birthday would be the date that he arrived at the zoo, where his anthropomorphized persona was born, and his birthday was frequently celebrated in a way similar to that of a human child’s, with soda and a cake.54 Samson was given a human name which recalled the biblical strongman and was referred to by his pronoun, and his admirers wished to see him memorialized after he passed away from myocardial fibrosis in 1981.55 As with the other case studies, Samson had a death mask taken to carefully record his features. This was used both as reference material for a taxidermy which was installed in the Milwaukee Public Museum in an exhibition titled “Samson Remembered” (overtly signalling the mount’s function as a memorial), and for a bronze statue of his head, which is positioned near the gorilla area in the Milwaukee County Zoo where he spent his days.

But Samson’s taxidermy differs from the average gorilla specimen in one crucial respect; it contains not one atom of the gorilla’s original biological body:

Samson the gorilla was another story. A 652-pound, overfed lowland gorilla from Cameroon, Samson was famous for slamming his fists against his Plexiglas window at Milwaukee County Zoo, delighting terrified visitors. One day in 1981, in front of his fans, Samson fell over and grabbed at his chest. Zoo vets could not resuscitate him; an autopsy revealed he’d had five previous heart attacks. Samson’s corpse was in the zoo’s freezer for years. When the Milwaukee Public Museum finally took possession, officials found the gorilla’s skin too damaged to mount. The museum tried putting Samson’s skeleton on display, but his bones were a weak evocation of the colourful ape. Samson wasn’t just dead, he was silenced. That troubled museum staff member Wendy Christensen […]. Christensen proposed resurrecting Samson through the taxidermy variant called a recreation — an artificial rendering of an animal that does not use the original animal or even its species. In 2006, 25 years after Samson’s death, she began fashioning the ape’s synthetic doppelgänger from scratch.56

The language of the journal article above presents Samson’s biography within a broader narrative of captive gorilla exhibition and locates Samson somewhere between living animal and embodied “story”, with a blend of zoological detail (“652-pound, overfed lowland gorilla from Cameroon,” an empiricism which carries echoes of the commodification of the nonhuman body) and storytelling whimsy (“one day in 1981”). The disintegration of Samson’s physical form is paralleled with silence, requiring a more recognizable vector than the one which the articulation of his bones can provide. The language of multiple narratives about the recreation emphasizes the transformation of the material Samson into something less tangible, namely his story. Yet visitors still require a vector for this narrative, an object which can function as a material link to the original biological animal. The taxidermist’s use of the death mask functions as a supposedly indexical connection to the organic Samson, through the need for a recognizable element of the animal: the face.

The installation of an entirely artificial Samson fits into longer traditions of museum representations of natural history; a desire to depict an animal not exactly as in life but as an idealized interpretation.57 It is an attempt to narrow the distance between human and nonhuman animals, “not necessarily to the animal itself but to the animal as imagined within a historico-cultural space”.58 While it is not unusual for a preserved animal to be composed of “only a fraction of the living specimen […] skin only or bones only,”59 nor for such taxidermy or anatomies to be composed of multiple materials, functioning as a kind of mixed media sculpture,60 (re)creating Samson with only synthetic materials and the impressions captured by plaster and film resonates with the apprehension of a final loss. The creation of a man-made body obscures both the anxieties raised by the cast of a deceased individual’s face and by the threat of extinction: “the connection between a body that is no longer there and a material thing that remains […] evok[ing] absences and, in their fragmentary character, imply[ing] disembodiment,”61 a push and pull between an intervention which prevents the final loss of Samson and the revelation that Samson is indeed gone.

The museum presentation subtly assuages these fears, for when Christensen took her masterpiece to the World Taxidermy Championships in 2009, a plaque was placed in his case to reassure visitors that this was not a permanent absence:

If you notice Samson conspicuously MIA from his usual haunts on the first floor, it’s because he is getting primped and papered [sic] for a competition! Museum Taxidermist/Artist Wendy Christensen-Senk will be taking Samson “on the road” to the World Taxidermy Championships in St. Charles, MO in May. She will compete with him in a category especially for re-creations. The World Taxidermy Championships are held every 2 years and there are around 1200 taxidermists in attendance (last time 29 different countries were represented) and over 800 mounted animals exhibited. This is the finest collection of taxidermy art ever displayed anywhere. The WTC is May 6–10. Samson will be away from the Museum from the middle of March until the middle of May. Please keep your fingers crossed and wish Wendy good luck! The competition is fierce and she and Samson will need it!62

The sign follows the trope of anthropomorphizing exhibits common to contemporary natural history museums, its language suggesting a still living individual who is being “primped and pa[m]pered” for a “road trip”. Christensen is depicted attaching synthetic hairs to the recreation, the juxtaposition of the living human face of the taxidermist and the face derived from the death mask, itself taken from the body of the original Samson, creating a sense of wonder over the artificiality of the gorilla’s body — even as the text proclaims its authentic identity as Samson. Indeed, it is from a narrative analysis of an account of the recreation’s construction as an object which successfully represents Samson that the death mask’s vital role in mediating historic tensions between wildlife conservation and museal forms of preservation can be discerned.

Investigative journalist Bryan Christy’s National Geographic article “Still Life” — covering Samson’s time at the World Taxidermy Championships (WTC) — indicates this interplay, its tagline stating that “in the taxidermist’s hands, even extinct animals can look alive. But preservation is one thing, and conservation’s another.” The article opens with an incident which emphasizes the shift in emotional reactions prompted by the artificiality of the body-object:

The incensed visitor is pointing at a mounted lowland gorilla as taxidermist Christensen teases a few hairs around the huge primate’s fingers. “I was in Rwanda,” the woman shouts, “and I know gorillas are protected!” […] Facing her accuser, she calmly explains that for three decades, Samson the gorilla was the star attraction at the Milwaukee County Zoo. The visitor apologizes, then gapes at what Christensen says next: This animal, a vessel for Samson’s story, contains no speck of real gorilla.63

The visitor’s outburst is one against which many natural history galleries attempt to undertake rear-guard action (the interpretation in the World Wildlife Gallery in which Alfred sits, for example, is at great pains to explain how collections praxis has changed and to highlight the historic nature of their collection, stating that the institution no longer accepts animals purposefully killed for taxidermy mounts). Christensen’s taxidermy occupies a liminal position, not physically composed of Samson, and yet with claims to being “more Samson” than the skeletal mount. Christy’s description of the object as an animal, a “vessel for Samson’s story” yet not a “real” gorilla figures a transubstantiation which preoccupies this article’s discussions around endangerment, preservation and conservation.

Christy situates this shift from preservation to conservation, from “real” primate to “story”, in the historical context of natural history specimen collection and construction, embedding the account of a hunting trip by the American Museum of Natural History taxidermist Carl Akeley with which this article began. Although this excursion resulted in one of Akeley’s most important works, “a mountain gorilla diorama whose figures were killed by his team in the Belgian Congo in 1921,” the trip “changed Akeley’s life,” for looking down on the silverback he had killed, Akeley declared that it required “all one’s scientific ardour to keep from feeling like a murderer.”64 This experience led to the taxidermist constructing not just a taxidermy mount, but Albert National Park sanctuary for mountain gorillas, for which he is recognized as “a forefather of gorilla conservation”.65 Akeley’s interventions are not limited to the development of a conservationist perspective. He is credited with inventing “a narrative framework for us to consider dead animals, one that continued to this day” originating in his creation of the first animal diorama at Milwaukee Public Museum in 1889, which now displays the recreation of Samson.66 Although interviewed participants at the WTC explain that “the key to taxidermy is telling the whole story,” Christy argues that “Samson the gorilla was another story,” perhaps because the recreation’s power as a relic had to be substantiated without the animal’s skin.67

All taxidermy occupies the uncanny territory of an inert object which appears almost alive, suggesting a not-quite-deadness through its physical proximity to the living animal. In the case of Samson, this physical connection is instead proffered through Christensen’s use of his death mask, troubling the authenticity of the biological animal through the supposed empirical powers of the copy:

Christensen molded a silicone face using Samson’s plaster death mask and thousands of photographs. She ordered a replica gorilla skeleton from a vendor called Bone Clones and a mix of yak and artificial hair from National Fiber Technology, the company that supplied fur for Chewbacca, of the Star Wars movies. For Samson’s hands she took molds of gorilla hands from the Philadelphia Zoo and reproduced them in silicone, right down to the fingerprints. Next, she rimmed his synthetic eyes with false eyelashes bought at Walmart.68

An immense attention is given to Samson’s face in an attempt to make it as accurate as possible, yet the skeleton is simply a ‘replica,’ with no indication as to whether this was modelled on the existing articulation of Samson’s bones. Although the primate’s fingerprints — another unique, individual and identifying aspect — have been replicated in incredible detail, they are not derived from Samson’s own fingers. As with Bobby, the use of Samson’s death mask reveals a fractured relationship to authenticity both through “the connection between the face of the dead person and the mold the mask represents to which an individual’s name is attached” and the implications, in the case of an object designed to create copies, of where originality might lie.69 Nonetheless, the plaster’s “authentic” preservation of the face and its central role in the creation of a reconstruction which holds more authenticity than the original bone mount demonstrates how Akeley’s anxiety about the tension between wildlife conservation and museum preservation remain relevant in the twenty-first century. The use of the facial plaster to authenticate the recreation also indicates our anthropomorphic attachment to a humanly recognisable element of Samson.

The recreation of Samson follows the trajectory of the death mask, an imprint which “connotes the absence” in which the original has not been cast from but “cast away”.70 “It is the corpse that has been excluded, leaving the death mask as its trace.”71 Samson’s artificial body, deemed more authentic than his skeletal mount through the death mask’s connection to the living animal’s recognisable face, signifies an individual whose story is supposed to synecdochically stand in for that of his entire species. It is important, then, that, as Christy’s tale concludes, Christensen not only triumphed over “world masters who’d brought their finest — and real — wildlife effigies,” but that “she did it without harming a single gorilla hair.”72

Beyond the Mask

As the three case studies examined in this article suggest, unlike other representations of animals, funerary plasters rarely stand by themselves as exhibit objects. As the case study of Bobby articulates, perhaps this is because, unlike taxidermy, which uses skilled artistic intervention to recall an animal to some semblance of life, casts more often inescapably capture an animal’s deadness; the popular image of Bobby has been crafted through artistry, and this is what the better-known death mask consequently conveys. This plaster functions as a representation of the level of artistry required to create a lifelike taxidermy mount, and, like the dermoplasty from which it is cast, functions as a portrait of the living animal. The original cast’s evident representation of mortality — of the post-mortem — must be contextualized by representations which conjure the life-essence of the individual in a way that a genuine death mask does not. None of the three case studies make use of the deathliness of the gorilla casts in their exhibition narratives, instead focusing on lifelike representations, despite the possibilities of such emotive objects to emotively depict loss or make visible the continued commodification of nonhuman animals.

Maybe this is because, as in the case of Alfred, the death mask has its own history connected with the preservation of human faces, a cultural heritage which draws on the traditions of portraiture, celebrity, and memorialization. Although these traditions can speak meaningfully to how we conceptualize charismatic megafauna and species ambassadors (especially when these are species visually similar to our own), the display of Alfred’s death mask reveals that such an object can be too troubling to function in an ambassadorial role. Alfred’s plaster simultaneously reveals that the formal similarities between human and nonhuman death masks play into the intense focus on the cultivated personality of the zoo celebrity and can drown out the plight of gorillas as endangered animals, moving too far over the troubled boundaries between human and nonhuman to complete a transition to celebrity artefact.

Finally, the authenticity bestowed upon the recreation taxidermy of Samson is conjured through the indexicality of the death mask on which the mount’s face is based. The story of Samson reveals that we struggle to recognize the constructed character of an animal known in life through, for example, a skeletal anatomy, requiring a face in order to read (or project) their anthropomorphized personality. In this instance, although the tradition of portraiture remains, the use of the death mask serves to retain a sense of capturing the original, authentic animal. Taxidermic preservation remains the apparent gold standard for natural history museum displays, and yet as Christy’s piece notes, Akeley’s anxieties about gorilla death, preservation and conservation still resonate with a modern-day audience: Christensen’s use of a death mask helps to authenticate the recreation by providing a connection to the biological body.

Examining animal death masks provides valuable insight into the techniques at play in natural history narratives, which use material remains to mediate stories about the other-than-human. While taxidermy, art installations and even skeletal mounts have received critical attention, death masks have remained less visible, both critically and within cultural and scientific institutions. As this analysis indicates, however, these objects can reveal vital and complex narratives about animal celebrity, the artistry of preservation, and the tensions between preservation and conservation. Death masks do not function like other imprints or animal remains; their representation of death is more overt than that of taxidermy, and in their rendering of the face, death masks are more recognisable as “characterful” to the human eye than a skeletal mount, while their display is often bound up with the cultural histories of human funerary plasters. Animal death masks could be used more frequently and more overtly to foreground historical commodification, tell conservation stories, forge an emotive connection to the individual, and confront viewers with the death of species: such objects can help us recognize the mortality of nonhuman animals, and to look them in the face.

Acknowledgements

Notes

-

Akeley, In Brightest Africa, 230.

-

Haraway, Primate Visions, 31.

-

Haraway, 31.

-

Haraway, 26–58; Kohlstedt, “Nature by Design”; Rothfels, “Preserving History”.

-

Dodd, Rader, and Thorsen, “Introduction”, 1. For more on how animals circulate meanings about and beyond the natural world, see Alberti, The Afterlives of Animals.

-

Alberti, “Introduction”; Morris, Mr Potter’s Museum; Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo; Pointon, “Artifacts”; Clymer, “Cromwell’s Head”; Barry and Burke, “Behind the Mask”. Research into animal death masks has largely been limited to exhibition catalogues, such as Near Life: the Gipsformerei — 200 Years of Casting Plaster (2019), which accompanied an exhibition that ran from August 2019 to March 2020 at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, and included the death masks of a boar, a wolf, a goat and a crocodile, as well as that of Knut, the famous polar bear of the Berlin Zoo.

-

Hylland, “Faces of Death”, 173.

-

Pointon, “Artifacts”, 172.

-

Benkard, Undying Faces, 44–45.

-

“Death mask”, National Museums Scotland. https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/collection-search-results/death-mask/673589.

-

Scott, “The ‘Missing Link’”.

-

Berger, Why Look at Animals?, 47.

-

Haraway, Primate Visions, 1.

-

Flack, The Wild Within, 120.

-

One telling example is the website findagrave.com, which allows users to upload photographs of individuals and their final resting place. The user “Gorilla Passion Project” has created 252 memorials with added photographs so that “people can see a face to match the loss of so many of these beautiful animals and just how human they are.” See https://www.findagrave.com/user/profile/48238259

-

Flack, The Wild Within, 185.

-

Cincinnati, “Too Sullen for Survival”, 169.

-

Hornaday, “The Zoological Park”, 543.

-

Scott, “Missing Link”, 2.

-

Scott, 9.

-

Nyhart, “Life after Death”, 237.

-

Scott, “Missing Link,” 6–8.

-

Nance, Animal Modernity, 83–84.

-

Nance, 24.

-

Malamud, Animals and Visual Culture, 36.

-

Shah, “Animal Life Stories”, 121.

-

Mitman, “Pachyderm Personalities”, 178.

-

Hermans, “Mona Lisa Smile”, 81. A full account of the exploitation of Bobby’s life has been reconstructed through clippings from contemporary literature in Christian Welzbacher’s Bobby: Requiem für einen Gorilla.

-

Hermans, “Mona Lisa Smile”, 81. An additional historical context for the taking of both human death and life masks was as reference material to advance racist arguments about human “types”. Such casts were often displayed in natural history museums in the second half of the nineteenth century; the same period also saw “human zoos”, such as those displaying people from Cameroon and Togo at the German Colonial Exhibition in 1896, whose body parts would be accessioned into various collections on their deaths. While this longer history is not presented in the contemporary display contexts of the death masks of Bobby, Berlin’s institutions are still grappling with the original purposes of many such plaster collections.

-

Hermans, “Mona Lisa Smile”, 81.

-

The history of taxidermy is fruitfully discussed in Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo. For an understanding of how this history overlapped with a shift in scientific representation, see Daston and Galison, Objectivity.

-

Kellogg, “Latter-day Taxidermy”, 142. Equally telling is the fact that Gerhard Schröder, one of the taxidermists who worked on the mount of Bobby, was appointed a member of the Sculptor Trade Association for his dermoplasty work. See Welzbacher, Bobby, 207–8.

-

Martin, Praxis der Naturgeschichte, 1:129.

-

Quoted in Welzbacher, Bobby, 203.

-

This is the case with bodily casts too, such as that of Knut, Berlin Zoo’s famous polar bear. Stein explains that a cast of a body also cannot be exact for the purposes of dermoplasty. In the case of Knut, he was lifted by two winches and placed into the desired position, but in death, the muscles are lax; the taxidermist cannot simply position the skin on top of the initial cast, as the fat layer has to be removed for preservation purposes, and the original skin would be too big for the cast. Instead, the muscles and fat have to be sculpted with clay, using the cast model as the base for this structure. In contrast, the body casts of amphibians and reptiles are deemed ‘better than the mount’ because the cast preserves the animal precisely as it was after death, whereas preserved organic matter is subject to degradation over time. These insights reveal value judgments about proximity to the original creature and to “nature”, at the same time as revealing the vast amount of artistic and interpretative work that goes into making this happen.

-

Such a practice is one indicator of the anthropocentrism present in natural history collections, preservation and display praxis. The human connection to the face allows us to identify the gorilla as more “individual”. Simian faces have similarities to our own, emote in an apparently legible fashion, and hold differences more readily recognizable as unique characteristics. In contrast, the gazelle face is more easily considered “other” and each individual less readily considered unique from an anthropocentric perspective.

-

“Der Gorilla Bobby”, Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, last updated 14 January 2014. Accessed via the Internet Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20140201234424/http://www.naturkundemuseum-berlin.de/ausstellungen/praeparationstechniken/gorilla-bobby/

-

Alberti, “Introduction”, 1. Dodd, Rader and Thorsen also take up this thread, stating in the introduction to their collection Animals on Display that “ways of representing animals are crucial to ways of thinking about, and ultimately interacting with, animals themselves.”

-

Alberti, “Introduction”, 9. For more on the historic links between post-mortem commodification and animal celebrity, see the chapter on “Jumbo” in Nance, Animal Modernity.

-

Flack, The Wild Within, 181.

-

Flack, 182–183.

-

Flack; Paddon, “Biological Objects”, 132–50.

-

Schuyler, “Death Masks”, 2.

-

Barnett, “The Dictator of Bristol”, 39.

-

Flack, The Wild Within, 120, 134.

-

Letter from Gerald A. Best to F.S. Wallis, 8 April 1948. Gorilla “Alfred” Collection, “Rowland Ward File”, Feb 1948. File 3023, Accession Number 29/1948.

-

The official page for the exhibition purports that to “highlight the seriousness of the wildlife extinction crisis, we have veiled Alfred the gorilla and 31 other animals in our World Wildlife gallery,” with the simian narratively both the star attraction and separate from the unnamed “other animals,” almost as a human celebrity supporting the cause. Thirty-two animals in the permanent exhibition — among them some of the gallery’s most charismatic megafauna, including the rhino, tiger, giraffe and chimpanzee — were obscured from view under funereal veils. As with the displaying of death masks, the museum’s use of visual culture commonly associated with human mourning alerted visitors to the dangers of permanent loss. The exhibition received a positive response from critics and audiences alike; the only complaint was that Alfred was hidden from view. See “Extinction Voices”, Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, https://www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/bristol-museum-and-art-gallery/whats-on/extinction-voices/

-

The issues raised by Remembrance Day for Lost Species co-founder Persephone Pearl about the Extinction Voices intervention have resulted in further decolonizing and environmental interrogation by the museum’s staff. The team are interrogating how the collection’s colonial legacies are at work in the World Wildlife Gallery’s permanent displays, and looking to new possibilities at exhibiting extinction futures. See Gladstone and Pearl, “Exhibition Voices”.

-

Morris, “Revealed”.

-

This is emphasized again by the reaction of younger visitors witnessed during this individual encounter, none of whom paid attention to other portraits or busts within the gallery. The mask of Alfred, by contrast, drew a significant amount of attention, in part perhaps because it is compellingly at eye height for children; yet, as with the artwork in Bristol Zoo, the children compared the mask (perhaps rather unflatteringly) to other humans they knew, a moment which signals a recognition of Alfred’s ability to trouble the human/nonhuman border. Such a reaction to the death mask emphasizes Paddon’s assertion that “anthropomorphic constructions connect audiences with animals” and especially that “in the societal psyche, animal celebrities such as Alfred can be placed near the center of a linear continuum between human and animal.” Paddon, “Biological Objects”, 144.

-

Letter from Best to Wallis, 8 April 1948.

-

Pointon, “Artifacts,” 178.

-

“Milwaukee’s Menagerie: Samson the Gorilla”, Milwaukee Public Library, https://www.mpl.org/blog/now/milwaukee-s-menagerie-samson-the-gorilla

-

Boyd, “Gorillas Samson and Sambo”.

-

“Samson #0021 Gorilla”, Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/141628052/samson-_0021-gorilla.

-

Christy, “Still Life”.

-

See Daston and Galison, Objectivity, 98.

-

Dodd, Rader and Thorsen, “Introduction”, 3.

-

Alberti, “Introduction”, 6.

-

For more on museum mounts as mixed media sculptures, in particular of fossil life, see Rieppel, Assembling the Dinosaur.

-

Pointon, “Artifacts”, 178.

-

Imig, “Samson the Gorilla”.

-

Christy, “Still Life”.

-

Christy, “Still Life”.

-

Christy, “Still Life”.

-

“The Man Who Made Habitat Dioramas”, AMNH, 19 May 2016, https://www.amnh.org/explore/news-blogs/news-posts/carl-akeley-dioramas

-

Christy, “Still Life”.

-

Christy, “Still Life”.

-

Pointon, “Artifacts”, 177.

-

Pointon, “Artifacts”, 178; my italics.

-

Pointon, 178.

-

Christy, “Still Life”.

Works Cited

Akeley, Carl. In Brightest Africa. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page, 1923.

Alberti, Samuel J.M.M. “Introduction: The Dead Ark.” In The Afterlives of Animals, edited by Samuel Alberti, 1–16. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011.

Barnett, Ray. “The Dictator of Bristol.” Nonesuch: The University of Bristol Magazine (Spring 1999): 38–40.

Barry, Anna Maria and Verity Burke. “Behind the Mask: Death Masks, Celebrity and the Laurence Hutton Collection.” Victoriographies 12, no.1 (2022): 10–30. https://doi.org/10.3366/vic.2022.0445.

Benkard, Ernst. Undying Faces: A Collection of Death Masks. Translated by Margaret M. Green. London: Hogarth Press, 1929.

Berger, John. Why Look at Animals? London: Penguin, 2009.

Boyd, Robert J. “Gorillas Samson and Sambo Adoptive Birthday Party.” 5 October 1955. Wisconsin Historical Society. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM49009.

Christy, Bryan. “Still Life,” National Geographic, August 2015. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/taxidermy-animal-preservation-museums.

Cincinnati, Noah. “Too Sullen for Survival: Historicizing Gorilla Extinction, 1900–1930.” In The Historical Animal, edited by Susan Nance, 166–83. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2015.

Clymer, Lorna. “Cromwell’s Head and Milton’s Hair: Corpse Theory in Spectacular Bodies of the Interregnum.” The Eighteenth Century 40, no. 2 (1999): 91–112.

Daston, Lorraine and Peter Galison. Objectivity. New York: Zone Books, 2007.

Daston, Lorraine and Gregg Mitman, eds. Thinking with Animals: New Perspectives on Anthropomorphism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

Dodd, Adam, Karen A. Rader, and Liv Emma Thorsen. “Introduction: Making Animals Visible.” In Animals on Display: The Creaturely in Museums, Zoos, and Natural History, edited by Liv Emma Thorsen, Karen A. Rader, and Adam Dodd, 1–11. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013.

Flack, Andrew. The Wild Within: Histories of a Landmark British Zoo. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2018.

Gladstone, Isla and Persephone Pearl. “Exhibition Voices, Extinction Silences: Reflecting on a Decolonial Role for Natural History Exhibits in Promoting Thinking about Global Ecological Crisis, using a Case Study from Bristol Museums”, Museum & Society 20, no. 1 (2022): 50–70. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v20i1.3806.

Haak, Christina, Miguel Helfrich, and Veronika Tocha, eds. Near Life: The Gipsformerei — 200 Years of Casting Plaster. Munich: Prestel, 2019. Ex. cat.

Haraway, Donna J. Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science. New York: Routledge, 1989.

Heise, Ursula K. Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Hermans, Ton. “The Mona Lisa Smile of Bobby the Gorilla.” European Journal of General Practice 1, no. 2 (June 1995): 81. https://doi.org/10.3109/13814789509160769.

Hornaday, William T. “The Zoological Park of Our Day.” Zoological Society Bulletin no. 35 (September 1909): 543–48.

Hylland, Ole Marius. “Faces of Death: Death Masks in the Museum.” In Museums as Cultures of Copies, edited by Brita Brenna, Hans Dam Christensen, and Olav Hamran, 172–86. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Imig, Nate. “How Samson the Gorilla Made Milwaukee Proud Years after Death.” Radio Milwaukee. 7 March 2017. https://radiomilwaukee.org/story/community-stories/samson-mpm/.

Kellogg, Vernon L. “Latter-day Taxidermy,” Science 22, no. 554 (1893): 141–2. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ns-22.554.141.b.

Kohlstedt, Sally Gregory. “Nature by Design: Masculinity and Animal Display in Nineteenth-Century America.” In Figuring It Out: Science, Gender, and Visual Culture, edited by Ann B. Shteir and Bernard Lightman, 110–40. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2006.

Malamud, Randy. An Introduction to Animals and Visual Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Martin, Philipp Leopold. Die Praxis der Naturgeschichte. Vol. 1, Taxidermie. 2nd ed. Weimar: Bernhard Friedrich Voigt, 1876. https://archive.org/details/diepraxisdernatu11mart/

Mitman, Gregg. “Pachyderm Personalities: The Media of Science, Politics, and Conservation.” In Daston and Mitman, Thinking with Animals, 175–95.

Morris, Pat. Mr Potter’s Museum of Curiosities. Trinity: Five Star Management, 1995.

Morris, Steven. “Revealed: 1950s Rag Week Students Who Stole Bristol Museum’s Stuffed Gorilla.” The Guardian, 4 March 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2010/mar/04/bristol-alfred-gorilla-theft-mystery.

Nance, Susan. Animal Modernity: Jumbo the Elephant and the Human Dilemma. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2015.

Nyhart, Lynn K. “Life after Death: The Gorilla Family of the Senckenberg Museum (Frankfurt/Main).” Endeavour 37, no. 4 (December 2013): 235–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endeavour.2013.08.001.

Paddon, Hannah. “Biological Objects and ‘Mascotism’: The Life and Times of Alfred the Gorilla.” In Alberti, The Afterlives of Animals, 132–50.

Poliquin, Rachel. The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012.

Pointon, Marcia. “Casts, Imprints, and the Deathliness of Things: Artifacts at the Edge.” The Art Bulletin 96, no. 2 (2014): 170–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2014.899146.

Rieppel, Lukas. Assembling the Dinosaur: Fossil Hunters, Tycoons, and the Making of a Spectacle. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019.