Placing Wild Animals in Botswana

Engaging Geography’s Transspecies Spatial Theory

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.10048

Andrea Bolla completed her Masters degree in Geography at the University of Guelph in 2009. Andrea lives in Botswana where she is conducting research on predator-livestock conflict.

Alice Hovorka is Associate Professor in Geography at the University of Guelph. Alice’s research focuses broadly on human-environment relations in Southern Africa; she is currently interested in the lives of animals in Botswana.

Email: eucdean@yorku.ca

Humanimalia 3.2 (Spring 2012)

Abstract

This paper engages transspecies spatial theory to illuminate the dynamics of human ‘placement’ of animals and resulting human-animal encounters through a case study of wild animals in Kasane, Botswana. It details the ways in which human conceptual imaginings and material fixing of wild animals are mutually constituted and grounded in human wonderment of and economic use value associated with nonhuman animals. Resulting interspecies minglings reinforce such placements through human’s fear-based responses and ‘problem animal’ discourses, ultimately re-placing animals into spaces where-they-belong. This paper highlights specifically geographical perspectives to further explorations of human-animal relations within the realm of critical animal studies.

Introduction

Geographers are well positioned to contribute to understanding of interspecies mingling within the realm of critical animal studies, given their grounding in spatial theory and their focus on human-environment relations as a central object of study. Animal geographers have joined the ranks of such scholars over the past two decades, and now consider nonhuman animals as beings with their own lives, needs, and even self-awareness, rather than as mere entities to be trapped, counted, mapped, and analyzed (Philo 54). More specifically, animal geographers explore how animals are “placed” by humans both conceptually and materially, invoking a transspecies spatial theory to explain and unravel the complexity of human-animal relations.

Our aim in this paper is to engage transspecies spatial theory and illuminate the dynamics of human “placement” of animals and resulting human-animal encounters through a case study of wild animals in Kasane, Botswana. First, we explore human imaginings of wild animals based on respect for and exploitation of nonhuman animals that together shape dominant conservation and tourism agendas, and fix wild animals in discrete “protected areas” across the landscape. Second, we explore the transgressions and mingling among species that emerge from such essentialist conceptual and material placements. These encounters reinforce human imaginings of wild animals by generating fear-based responses and “problem animal” discourses, which ultimately reaffirm ideas and practices associated with wild animals’ proper place as being within bounded spaces. We offer an explicit overview and engagement of animal geography theory, emphasizing human placement of animals as a key tenet to understanding human-animal relations. Further, this article features an empirical study of specifically African interspecies mingling, a topic which to date has not featured prominently in critical animal studies or animal geography scholarship.1

Transspecies spatial theory

Humans place animals in a variety of imaginary, literary, psychological, and virtual spaces, as well as in physical spaces as diverse as homes, fields, factories, zoos, and national parks. This occurs through classification schemes whereby humans neatly identify, delimit, and position animals in their proper conceptual and material space relative to themselves and to other animals (Philo and Wilbert 5-6). Such placements dictate where animals belong, where they should go, how long they should stay, how they should behave, what use they have (to humans), and how humans interact with them. In turn, these placements are necessarily spatial and have important consequences for the extent to which different animals are included and/or excluded from particular spaces (Philo 51-52). Certain types of animals are contested and excluded from human homes and neighborhoods because they are deemed wild, dangerous, or unhygienic, while others are included because they are considered tame, clean, or charismatic (Philo and Wolch 108). Many human discourses contain within them a definite imaginative geography, which serves to position “them” (animals) relative to “us” (humans) in a way that links the conceptual “othering” (setting them apart in terms of character traits) to a geographical “othering” (fixing them in world places and spaces different from those that humans tend to occupy) (Philo and Wilbert 10-11).

Space, while appearing initially unproblematic, takes on an active role in the production and reproduction of human and animal positionality. Space is never simply where things happen (Wolch and Emel xiv) or a stage for human action, innocent in its role in shaping human affairs. According to Lefebvre, “space is a social product... [T]he space thus produced also serves as a tool of thought and of action... [I]n addition to being a means of production it is also a means of control, and hence of domination, of power” (Lefebvre 26). Rather, the spatial expression of species hierarchy across the physical landscape reinforces ideas about the proper place of particular animals (and particular humans) and animals in relation to humans. Power relations between humans and animals are actively engaged through space as based on human placements (of animals) and animal transgressions (of human placements). Although conceptual and material placement of animals by humans often results in a stark, essentialized, fixed spatial expression (where humans prefer animals to remain outside the perimeter of human existence), in reality there exists a more complex imaginative geography of animals whereby human-animal encounters are varied, multi-dimensional, and frequent.

Further, the human-animal relationship is not one-directional, with only humans exerting power and agency through placement of animals; animals also exert their own power and agency through actions and potential intent. Animals often end up accepting, evading, or transgressing the places to which humans seek to allot them. Some animals can be taught which places are out of bounds, while other animals will wander in and out of the relevant human spatial orderings without necessarily knowing that they are doing this (thus ranging from transgression of to resistance to human spatial practices) (Philo and Wilbert 22). Ultimately, the extent to which animals accept, evade, or transgress the places to which humans seek to allot them reinforces or counters human placements, generating a relational negotiation of physical boundaries and discursive imaginaries. To this end, animals themselves figure in socio-spatial practices of inclusion/exclusion and are influential actors in the human-animal relationship. Whatmore describes this as a “relational effect generated by a network of heterogeneous, interacting components whose activity is constituted in the networks of which they form a part” (Whatmore 28). As such, the role and significance of animals is essentially produced and developed through encounters between people and animals whereby human spatial practices are based on economic, political, social, and cultural requirements, and animal agency comes in relation to such practices (Philo and Wilbert 24). Spatial inclusions and exclusions of particular animals by humans are bound up in the more symbolic dimensions of encounters between humans and animals, which animal geographers attempt to unravel by teasing out the numerous social, political, economic, and cultural pressures shaping these relationships (Philo and Wolch 110). On the ground, human-animal and spatial relations are scrambled and destabilized in a number of ways that makes the dual conceptual and material placements of animals both extremely interesting and difficult to decode.

Transspecies spatial theory, as detailed above, reflects foundational tenets of animal geography scholarship aimed at illuminating the place of animals in society and disrupting the assumed dichotomy between humans and animals. Since the mid-1990s, these core concepts have been applied to and extended through various case studies documenting human-animal relations. Of particular relevance to this paper are recent animal geography extensions into transspecies urban theory, which challenge the ideas that cities are the exclusive domains of humans (Wolch 726) and that animals do not live or belong in urban (human) space. Empirical studies illuminate the minglings and transgressions that occur when animals (as assumed non-urban dwellers) enter into or reside within defined “human” space of the city. Possums in Sydney, Australia, monkeys in Singapore, and chickens in Gaborone, Botswana, as well as broader commentaries on cattle in London and Chicago and attitudes towards animals in Los Angeles, USA, provide insights into the intricacies of human-animal relations despite the rigid ways in which humans define the place of animals as necessarily “outside of” cities.2 Recognizing the presence or even agency of urban animals (whether permanent or transient) is essential when detailing and explaining urban form and function, as well as daily lives of urban residents. This paper extends transspecies spatial theory beyond these urban iterations to include non-urban areas (thus considering both Kasane Township and Chobe Park in Botswana) and multifaceted interspecies mingling that occurs when animals transgress into human areas (Kasane) and humans transgress into animal areas (Chobe). It also offers an empirical study of specifically African human-animal relations, which to date has not featured prominently in animal geography scholarship or critical animal studies.

Methodology

Interpretivist in nature, this empirical investigation of wild animal placement in Botswana uses qualitative research design to facilitate inductive contextualization and “thick description,”3 capturing human perceptions, beliefs, and meanings associated with animals. It develops geographical constructs of conceptual and material placement through in-depth examination of and exposure to human-wild animal encounters, instead of entering the field with a set of given constructs or assumptions of how those encounters evolve or ultimately occur.4 It acknowledges the situated knowledge of human subjects involved in the research, recognizing that knowledge is based on social constructions of reality and mediated through the positionality of both the researcher and the researched.5 In this case, animals are represented through interpretations of human researchers and human respondents.

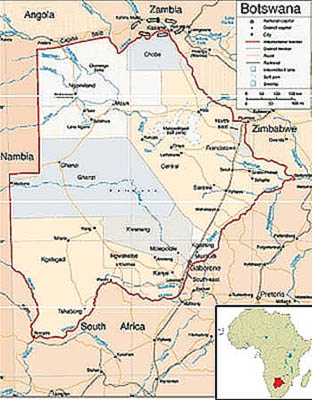

Figure 1

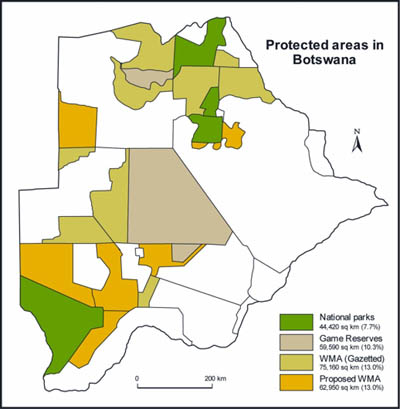

Our investigation features Botswana as a study site, a landlocked nation bordered by South Africa, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe (see Figure 1). Botswana’s human population of 2,065,398 (Government of Botswana http://www.gov.bw/en/ accessed January 26 2012). is relatively small in proportion to its vast terrain, resulting in a low mean population density of approximately three persons per square kilometer (United Nations Environmental Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Programme). Botswana’s wild animal population is extensive and diverse. Of the twenty-seven central species featured in the nation’s wildlife statistics for 2006, ranging from elephants to baboons, eland to ostrich, there is an estimated population of 454,246 wild animals (Republic of Botswana, “Botswana Environmental Statistics”). Notably, the nation is home to the largest population of African elephants, at approximately 120,000 to 150,000 in the northern region (Republic of Botswana, “Wildlife Statistics”). Eighteen percent of the country’s land is designated as protected areas, consisting of four national parks (Gemsbok, Chobe, Nxai Pan, and Makgadikgadi Pans) and three game reserves (Central Kalahari, Moremi Wildlife, and Khutse), which contain and conserve the nation’s wild animals. An additional twenty-one percent of lands are defined as Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs), which are stretches of land bordering protected areas, acting as buffer zones and migratory corridors to support the ecological functions of protected areas (Republic of Botswana, “Wildlife Statistics”) (see Figure 2). Almost ninety percent of Botswana’s human population lives along the better-watered, more fertile eastern regions along the north-south band, which follows the main road and rail routes linking South Africa, Botswana, and Zambia.6This stretch of land hosts the urban centers of Gaborone (the capital city, largest human population) and Francistown (the country’s most industrialized urban center, second largest human population), as well as other major human settlement areas, including Palapye, Serowe, and Mochudi.

Figure 2

Data collection took place from May to July 2008 and included purposive, semi-structured interviews, secondary data review, and participant observation. Interviews were conducted in English with fifty-seven people, including local citizens, natural and social scientists, researchers, representatives of local and foreign non-governmental organizations, international conservationists, tourism operators, traditional leaders, and government officials at the Ministry of Environment, Wildlife, and Tourism and the Department of Wildlife and National Parks. The broad range of respondents facilitated rich and diverse insights into environmental values, ideas about appropriate human-animal relations, and the extent of local knowledge of and experience with various types of wild animal.7 Identification of the study sample occurred through snowball sampling, whereby each respondent interviewed was asked to identify other potential respondents with the target characteristics.8 Secondary data included a review of academic literature on wild animals in Botswana from the perspectives of cultural and physical geographers, ecologists, biologists, and policy analysts; sites of public discourse, such as print media, national policies, laws and programs dealing with wild animals; media campaigns; documents supplied by government and NGOs; and written stories and folklore about wild animals. Participant observation occurred through informal conversations, direct observation, and active participation in activities that facilitated first-hand encounters (e.g. accompanying government officers on game drives, encountering wild animals in homesteads, etc). While Kasane, Chobe District, features as a case study for this paper, data collection took place in various locales in Botswana.

Data analysis was informed by literature reviews, secondary data, interview transcripts, field observations, and prior knowledge/capacity to recognize themes in the data. Primary and secondary data were analyzed by means of content analysis, a coding scheme for artifacts of social communication.9 Two separate stages of content analysis were conducted: revealing themes from semi-structured interviews and secondary data, and establishing potential links between the conceptual and material placement of wild animals in Botswana. Textual passages were examined for internal meanings, assumptions, and beliefs, and extracted passages were then organized according to emerging themes. Passages associated with each theme were examined further to create more specific, refined ones, which were organized under three chief categories: what constitutes “wildlife,” wild animals as a useful natural resource (positive perceptions), and wild animals as harmful (negative perceptions). Individual themes (sub-categories) within the latter two categories include: wild animals as economic development tools, as integral to ecological systems, as recreationally valuable, as a source of nutrition, and as symbols, which are linked to wild animals as a useful natural resource, while threats to pastoral livelihoods and human lives were identified as sub-categories for conceptualizations of wild animals as harmful. In the first stage of analysis, the three sets of themes were examined for inter-relationships and situated within the context of the broader literature review. In the second stage of analysis, data was triangulated by merging information from secondary data, interviews, and observations in order to link wild animal discourses and social constructions with material places and reveal relations between humans and wild animals in particular spaces

Placing wild animals

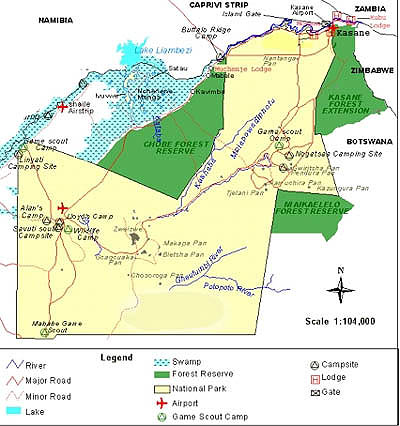

Both humans and wild animals inhabit and live in Kasane, Botswana, within a large variety of discursive and spatial settings, and meet one another through frequent and multi-faceted encounters. Wild animals are “imagined” or conceptually placed through human ideas and classifications wrapped up with both human respect for and exploitation of, in particular, charismatic fauna such as lions, leopards, elephants, buffalos, rhinos, zebras, and giraffes. Wild animals are also “fixed” or materially placed in discrete spaces across the landscape, specifically within Chobe National Park (see Figure 3), which contain animals that are the source of both human wonderment and economic use value. Yet these essentialized placements are more complex in everyday life: humans move in and out of the national park while wild animals move in and out of the human settlement of the Kasane township. Such interspecies encounters generate fear-based responses and “problem animal” discourses, which in turn reaffirm ideas of the proper place of wild animals, and justify practices that keep them contained within these discourses. The remainder of this paper details human-wild animal relations in Kasane, Botswana, through the lens of transspecies spatial theory.

Figure 3

Imagining & fixing

Imaginaries of African wildlife in popular culture evoke scenes of exotic animals running freely and exuding raw untamedness across wide-open savannahs. Indeed few scenes of nature are more breathtaking for humans than giraffes gliding gracefully through the acacia landscape or a family of elephants frolicking at a watering hole or a lion sitting majestically amongst the tall grass (see Figures 4 and 5). Human wonderment at such charismatic fauna has spurred enthusiasm for containing them, for example within national parks, conservation areas, and game reserves, in order for both gazing upon them and protecting them from humanity. In turn, the ecological valuing of wild animals, and the ethical belief that they should be sheltered from humans, have provided humans with numerous economic benefits. Wild animals as resources for and foundations of tourism activities have generated income and national pride, ultimately reinforcing protectionist paradigms in the human-animal relationship. Further, protectionism takes on a spatial expression necessarily delineating rigid boundaries and containing “us” in human settlements and “them” in protected areas.

Figure 4: Photo by Aneta Karnecka

In Botswana, the physical placement or fixing of wild animals in discrete spaces emerged largely from the contemporary international conservation agenda. Traditionally, local chiefs held ownership and responsibility for wild animals, focusing primarily on hunting activities for self-sufficiency for hundreds of years,10 with animals left to roam freely across the landscape. The British colonial government installed in 1885 a “fortress” style of conservation based on a largely state-owned and centralized resource management scheme.11 Under this scheme, wild animals were reified as exotic beings and government officials established bans, quotas, and licenses to limit indigenous hunting practices.12 To some extent wild animals were privileged over indigenous humans during the colonial period and Euro-American ideas of conservation became prominent conceptualizations with regard to the human-animal relationship based on the uniqueness of Africa’s “Eden” of wild animals.13 State preservationist policies led to the establishment of two Protected Areas during the early 1960s, namely Chobe Game Reserve (1960) and Central Kalahari Game Reserve (1961).

Figure 5: Photo by June Liversedge

At the same time, however, several aspects of colonialism in Bechuanaland (now Botswana) were exceptional in the region, whereby tribal authorities continued to hold legal rights to benefit from wildlife, and some rights of management; while game was ultimately state property, hunting concessions enhanced tribal coffers.14 Further, Bechuanaland did not have strict laws and practices of racial segregation found in other southern African nations, with many local settlers marrying Africans and with social networks exhibiting an exceptional degree of cross-cultural communication. Thus, preservationist policies in Botswana were not only the product of European conservationist ideas. They also emerged through converging views of conservation amongst disparate groups, including chiefs, hunters, white adventurers, and international organizations, all of whom came to see preservationist policies as being in their interest. Establishment of Moremi Park (1965), for example, emerged from localized practices protecting wildlife from depredations of illegal South African hunting parties and ensuring future domestic use.15 Protectionist conservation agendas in Bechuanaland, and later Botswana, therefore influenced human-animal relations through the physical (spatial) separation more so than through state political appropriation and control over wild animals.

At Independence in 1966, the Government of Botswana continued its conservationist agenda by establishing Chobe National Park (1967), Makgadikgadi Pans and Nxai Pans (1970 as game reserves, 1992 as national parks), and Khutse Game Reserve (1971). In addition to protected areas aimed at wild animal conservation, Wildlife Management Areas (established through the Tribal Grazing Land Policy of 1975) serve as corridors for migratory species between protected areas; these also act as buffer zones between human settlements and protected areas (Republic of Botswana, “Botswana Environment Statistics”). In 1989, the government decentralized its wild animal management scheme to further include local communities living close to protected areas in decision-making structures; the aim of community-based natural resource management is to allow local communities increased benefits from containment of wild animals for conservation and tourism purposes.16 This recent conservation trajectory reinforces the importance of separating wild animals from humans in order to protect the former (and possibly the latter, as is discussed later), yet reduces local human concerns regarding their lack of access to animals.17 Land allocations continue for the purposes of wild animal conservation, including Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (2000) and the Kavango-Zambezi Trans-Frontier Conservation Area (currently under development).

The physical arrangement and delineation of animals from human zones is reflected in the Kasane area of Botswana, located in the northern-most Chobe District, at the corner of the Caprivi Strip of Namibia to the north and west, Zambia to the north, and Zimbabwe to the east (Republic of Botswana, “Population and Housing”) (see again Figure 3). The primary wild animal zone is Chobe National Park. The area originally hosted a large settlement whose inhabitants were the San people (Basarwa). They were hunter-gatherers who lived by moving from one area to another in search of water, wild fruits, and animals. The San were later joined by groups of the Basubiya people and later, around 1911, by a group of Batawana led by Chief Sekgoma. When the country was divided into various land tenure systems early in the twentieth century, the larger part of the area that is now the national park was classified as crown land. The idea of creating a national park was first inspired by the desire to protect wild animals from extinction and to attract tourists. In 1932, 24,000 square kilometers in Chobe District was declared a non-hunting area. The following year, the protected area was increased to 31,000 square kilometers. A decade later, heavy tsetse fly infestations led to the project’s collapse. In 1957, a reduced area of 21,000 square kilometers was proposed as a game reserve. It was then gazetted as Chobe Game Reserve in 1960, and seven years later was declared a national park totalling 10,589 square kilometers (Republic of Botswana, “Botswana Environment Statistics”). In 1975, the large settlement based on the timber industry at Serondela gradually moved out, and Chobe National Park was finally “emptied of human occupation.” Finally, in 1980 and 1987, the boundaries were altered to increase the park to its current size (Botswana Tourism Board, “Tourism Board”). Chobe National Park is home to a variety of animal species and hosts the largest population of elephants on the African continent, with an estimated 30,348 individuals living in the park (Republic of Botswana, “Wildlife Statistics”). The riverfront also provides a vital source of water, particularly during the dry winter months, for large herds of Cape Buffalo, along with waterbuck, lechwe, puku, giraffe, kudu, roan, sable, impala, warthog, bushbuck, monkeys and baboons, together with predators such as lion, leopard, hyena, and jackal, converging upon the river to drink. The river also supports populations of hippopotamus and crocodile (Botswana Tourism Board, “Travel Companion”). The township of Kasane is the primary human settlement, situated on the south bank of the Chobe River and the north-eastern boundary of the Park (Republic of Botswana, “Chobe District”). Kasane has experienced an average growth of 5.83 percent between 1991 and 2001 with 7,638 people living in the town and village (Republic of Botswana, “Population and Housing”). Its strategic location along the main tourist sites, namely, the Okavango Delta and Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, and its recognition as an international tourist destination, have led to its recent expansion and to increased tourism-related employment opportunities for Batswana people (Republic of Botswana, “Chobe District”).

Botswana’s wild animal management strategy has long been grounded in environmental discourse that privileges “pristine nature” in ecologically demarcated zones of “wilderness.”18 While humans are established as gatekeepers of these zones, they are clearly identified by scientists, conservationists, and government officials as the “other” who does not belong. According to the Botswana Tourism Board, “Parks and Reserves have been established for the protection of the wildlife. Here, in the wilderness of Botswana, it is you who are the intruder and your presence is a privilege” (Botswana Tourism Board, “Botswana Tourism Board”). Hence, socially constructed “wildlife places” exist beyond the realm of human occupation, intervention, and control, where humans are necessarily and literally out of place. These spaces are reserved as sites of quiet observation based on the belief that, as one local tourist operator put it, “animals are not to be disturbed [by people] in their territory.” Further, wild animals and their designated spaces are viewed as key components in broader environmental models of harmony and sustainability.19 As noted by a senior game reserve staff member: “Wildlife is necessary to maintaining an ecological balance. Without wildlife everything [would be] out of kilter.” A volunteer at Cheetah Conservation Botswana echoes this sentiment saying, “[Wildlife is] part of the ecology, part of the system.... So, how can it not be there? It doesn’t make sense.” Finally, Botswana’s wild animal management strategy is grounded in ethical discourse recognizing the intrinsic value of animals, well beyond their utility to humans.20 Local conservation agencies frequently engage this ethical principle in campaigns soliciting support and funds. Cheetah Conservation Botswana, for example, highlights the cheetahs’ unique physiology, specifically its ability to achieve “breathtaking acceleration” and speed, as a means of urging people to commit to its protection (Cheetah Conservation Botswana).

Through the conservation agenda, humans imagine wild animals in Botswana as part of pristine nature and as ecologically valuable beings with intrinsic value. The spatial implications of this agenda emerge from human containment of wild animals into fixed spatial boundaries of protected areas essentially “for their own good.” Yet the containment of animals in a fishbowl is also “good for humans,” given the income generated from tourism founded upon the viewing of (or hunting and killing of) animals. Hence, human wonderment at wild animals, the catalyst in part for the conservation agenda, has met up with an objectification of “them” for economic gain. As such, human ecological imaginings of wild animals are necessarily wrapped up with socio-economic valuing of them. According to a DWNP staff member, “wildlife conservation is very important in Botswana because without wildlife our economy would suffer,” or, as a local citizen noted, “we have to protect [wild] animals because they give us employment. People have jobs because people come from all over the world to see the animals we have.”

The Government of Botswana is actively promoting wild animal-based tourism as an alternative engine of growth to strengthen and diversify the economy (Republic of Botswana, “Botswana Environment Statistics”). The sector currently stands as the second largest contributor to Gross Domestic Product (9.5 percent), generating US$1.6 billion per annum, second only to the profitable diamond mining industry (World Travel Tourism Council). Approximately 15,000 people are directly employed in this sector with an additional 58,783 people employed indirectly, representing 10.6 percent of total employment (Botswana Tourism Board, “Tourism Industry”). It is projected that by 2018, tourism’s GDP contribution is expected to rise to 11.9 percent of GDP or approximately US$2.4 million and to employ 13.2 percent of the human population (World Travel Tourism Council). In Kasane, wild animal tourism directly employs forty percent of the people (World Travel Tourism Council; Atlhopeng, et al.) and provides employment indirectly to industries such as art galleries, internet cafes, and souvenir shops. Wild animals are encountered through game drives, guided walks, boat cruises, elephant-back safaris, a crocodile farm, a snake park, and walks with meerkats. The tourism board urges visitors to “feel the rush of adrenalin as a lion seeks its prey in Savuti or elephants in the Chobe feed just beside your vehicle” (Botswana Tourism Board, “Bajanala”). As one Kasane resident explained, “It’s nice to have animals because it brings tourists. We are working here because of tourists; we are paid because of them. If they are not coming, it means there will be no business. That’s why I think it is important to have [wild animals].” Furthermore, the economic contribution of wild animals extends to community and household levels by way of CBNRM programs where local trusts and individual households benefit directly from locally organized viewings or hunts of particular species.21 As of 2002, community-based organizations involved in CBNRM generated approximately 84.5 million Pula (approximately USD13 million) (Republic of Botswana, “Wildlife Statistics”).

In sum, wild animals are imagined as exotic beings and as representatives of pristine nature that must be conserved and protected for their own good, as well as for humans’ moral satisfaction and personal enjoyment. That wild animals, through their containment in protected areas, bring economic gains to human citizens of Botswana further reinforces and justifies their place in discrete spaces across the landscape, separate from human settlements. Hence human conceptual and material placements of wild animals are mutually constituted and grounded in human wonderment at and economic use value associated with these nonhuman animals.

Transgressing & mingling

Both humans and wild animals move across the physical boundaries of Chobe National Park and Kasane Township, thus transgressing the essentialized placements as detailed above. Humans move in and out of the national park to gaze at wild animals, while wild animals move in and out of the human settlement to explore and forage. The resulting interspecies mingling is dynamic and multi-faceted, and reflects more complexity of human-animal encounters than human practices of placement suggest.

On the one hand, humans use and inhabit Chobe National Park through numerous tourism and conservation activities. For example, camping is permitted in designated areas, albeit in limited numbers, and Chobe Game Lodge offers more luxurious accommodation for safari tourists; game drive trucks and boats comb the landscape continuously during operation hours. Other activities revolve around conservation and protection of wild animals: the Department of Wildlife and National Parks maintains park infrastructure, and the Anti-Poaching Unit patrols the area to deter illegal hunting. Researchers and scientists also maintain a presence in Chobe National Park, conducting aerial and ground population surveys, or in-depth biological studies, such as those of lion or elephant populations around Savute Camp. Given this human presence, wild animals have become habituated to people, their vehicles, and their machinations (see Figure 6). It is not uncommon to observe numerous safari vehicles converge on a particular place to ensure tourists come away with authentic safari experiences. This was the case during field research in 2008, when tour operators spotted two lions eating an impala along the riverbank; within moments, five vehicles and three boats surrounded the scene, yet the lions seem undeterred by the audience. These scenes are commonplace within the park boundaries. Wild animals nevertheless become agitated by humans: for example, elephants often “mock charge” vehicles deemed too close. Safari operators are mandated to keep respectful distance, however, to avoid such provocations. Ultimately, these encounters of wild animals by humans within Chobe National Park reaffirm human wonderment at animals, justifying rationales for containing them for their own protection and generating tourist dollars through their viewing.

Figure 6: Photo by Andrea K. Bolla

On the other hand, wild animals use and inhabit Kasane Township despite official efforts to keep them within park boundaries. Warthogs, for example, have become regular town residents, frequenting grocery stores and roadsides, and humans have become habituated to their presence and familiar with their behaviors. Warthogs have integrated themselves into the form and rhythm of Kasane; humans refer to them as “only warthogs” living around and with them, and express mild annoyance when the warthogs unexpectedly wander into traffic. Larger animals, such as elephants, also frequent Kasane streets or riverbank areas, as evidenced by the billboard in Kasane shown in Figure 7; hippopotami, hyenas, buffalo, leopards, and lions often come during hours of darkness to scope out food and water sources. Wild animal transgressions into human spaces may be attributed to a variety of motivations. For example, animals may be searching for food sources (e.g. warthogs seeking out garbage piles or elephants seeking out tree foliage) that are easy to attain or simply available, given “overcrowding” in Chobe Park as found in a recent wildlife survey commissioned by the Government of Botswana (elephantswithoutborders.org). Transgressions may also be attributed as a consequence of the natural habitat range of key species who necessarily traverse the landscape beyond park boundaries.

Figure 7: Photo by Andrea K. Bolla

Some Kasane residents see animals as a part of their daily experience that they enjoy. As one participant explained, “It’s nice to have animals because it’s entertaining. Because where there [are] no animals, it’s like boring.... Let me take a walk and see something,” and “The elephant and buffalo, they are just behind my house because where I am staying, it’s at the end; it’s the bush and in the evening they start walking, elephants and buffalo. You start hearing hyena and lions.... It’s nice.” Humans are at times empathetic for such transgressions, noting animals “getting lost” and ending up in the town. At times people are annoyed at their presence, such as one resident who remarked: “Elephants are very dangerous. They will just come right up near the house where the children are and eat the food I grow for my family. They have enough food out there and should not be coming here to eat.” The majority of human Kasane residents, however, fear wild animals transgressing national park boundaries, viewing them as harmful, dangerous, and threatening. Stories abound of wild animals inflicting injury or death on humans. Numerous participants recalled media reports to illustrate the need to keep animals within the park. One resident stated: “[Elephants] attack some of the people; I can’t remember how many, but more than five. [Elephants are] dangerous.” Another participant spoke of a story she had heard in the community: “[A] taxi driver says that Zimbabwean ladies were attacked by elephants. Now I am afraid of animals.” Human residents discuss strategies to manage fearful encounters. One noted, “[We] ask [each other] how to tackle this animal because they are all over. They say if you see a hyena you have to take something like a log and put it on top of your head; it won’t attack you.” Others had individualistic strategies: “If I come across a certain animal I can just walk away without disturbing it. May be dangerous if you come up very close, but if you are a distance away it will not harass you. If very far, you can just walk. If it is where you are going, go back. Do not proceed. Go back.” Kasane residents take measures to avoid wild animal encounters by, for example, not traveling by foot after dark. Fear of wild animals is closely connected not only with bodily harm and fear of encounter, but also with threat to human livelihood, especially damage to crops and livestock, given increased competition for space and food amongst various animal species.22 In Kasane, the lack of molapo farming (crops produced on arable flood plains), which is common in other settlements found along the river, is largely attributed to destruction by wild animals of crops and livestock (Republic of Botswana, “Chobe District”). Parry and Campbell conducted studies in the Chobe Enclave and Mababe Depression, which revealed that 78 percent of crop farmers and 59 percent of livestock owners complained of crop raiding by wild animals. Schiess-Meier, et al., examined the impact of wild animal predation on livestock in the Kweneng District, claiming that 0.34 percent of the livestock in the region (or 2.2 percent per farmer) were being depredated annually (1269-1270).

In sum, while human transgressions into Chobe National Park generate interspecies minglings that reaffirm wonderment at wild animals, animal transgressions into Kasane Township generate minglings that largely inspire fear. This in turn has major implications for further human conceptual and material placements of wild animals, as discussed below.

Re-Placing

Interspecies encounters primarily generate fear amongst human Kasane residents and thus facilitate and justify numerous practices that serve to re-establish wild animals in their “proper” place. This re-placement occurs through everyday activities physically to keep wild animals away from humans, and through broader discourses highlighting “problem animals” to reaffirm the need to do so. First, DWNP staff regularly patrol Kasane Township, and coax or chase wild animals back to Chobe National Park using scaring techniques, such as gunshots or thunder flashes, to remove them and deter them from returning. Government encourages preventative techniques in addition to these reactive ones, encouraging farmers to practice proper husbandry methods (e.g. kraaling domestic animals at night) or natural means (e.g. chili pepper for elephants) to deter wild animals (Republic of Botswana, “Botswana Environment Statistics”; Republic of Botswana, “Wildlife Statistics”). Recent infrastructural developments in Kasane include electrified game fences to keep wild animals within the park boundaries. This has decreased available corridors and physical spaces for animals, and increased conflicts among wild animal species. Stand-offs between elephants and baboons, for example, occur with increasing frequency as both groups try to access Chobe River. Other practices involve translocation of individual animals by government or by human citizens; tranquillizers and cages are used to subdue the animals in question and they are whisked away to areas some distance from human zones. Outright killing of wild animals is prohibited, save for the most extreme cases. Anecdotal evidence, however, points to the increasing frequency of animal death at the hands of, in particular, local farmers.

Second, these human practices to keep wild animals contained within Chobe National Park are both justified and reinforced by broad discourses of “problem animals” expressed through both tourism and government agendas. Tourism brochures, for example, state:

Approach big game with caution; don’t make any unnecessary movements or noise, and be prepared to drive on quickly if warning signs appear (if, for instance, an elephant turns head-on to you and flaps its ears). Keep down-wind if possible; remember that just about any wild creature can be dangerous if startled, irritated or, most importantly, cornered. Do not under any circumstances cut off an animal's line of retreat. (Botswana Tourism Board, “Tourism Board”)

These instructions reaffirm separation of humans from wild animals and establish proper behavior of humans when in national park areas. Further, problem-animal discourse is a major fear mechanism through which humans imagine and fix wild animals into national parks. The government recognizes the challenges of interspecies mingling, particularly outside of park boundaries, given that wild animals can negatively impact humans; it identifies particular “problem animals” as those posing a threat to human property, lives, and livelihoods, and those difficult for humans to defend themselves against (Republic of Botswana, “Wildlife Statistics”). Those labeled problematic for 2003 include lions, leopards, elephants, hyenas, wild dogs, and cheetahs at the top of the list. Other species with numerous recorded human ”incidents” include kudus, jackals, crocodiles, pythons, hippopotami, baboons, steenboks, porcupines, buffalo, caracals, and duikers (Republic of Botswana, “Wildlife Statistics” [67]). In Chobe District, a total of 304 “problem animal incidents” took place with mortality culminating in the killing of 30 lions, 84 leopards, 5 hippopotami, 42 elephants, 4 cheetahs, and 2 each of buffalo, crocodiles and wild dogs (Republic of Botswana, “Wildlife Statistics” [69-70]). In June 2010, two young problem elephants were killed when they entered the yard of a Kasane resident. Such incidents and general conflict between humans and wild animals is escalating, given animal transgressions into Kasane Township, as well as with the expansion of human activities into areas previously dominated by wild animals (Republic of Botswana, “Wildlife Statistics”).

Conclusion

This paper illuminates human placement of and encounters with wild animals in Kasane, Botswana. Human imaginings of wild animals based on both respect for and exploitation of nonhuman animals together shape dominant conservation and tourism agendas, and fix wild animals into discrete protected areas across the landscape. Yet humans and wild animals transgress their designated spaces and mingle with one another in Chobe National Park, as well as in Kasane Township. These interspecies encounters are dynamic and multifaceted; they generate both wonderment (for human tourists within the park) and fear (because of wild animal presence in and around the town). Such encounters reinforce and justify human imaginings and fixings of wild animals, prompting fear-based responses and “problem animal” discourses, and re-placing animals into where they belong.

This explicit engagement of transspecies spatial theory highlights human conceptual and material placement of animals as a key tenet to understanding human-animal relations. It also brings to the fore geographical perspectives within critical animal studies in order to further explore the ways in which humans position themselves relative to animals and how these dynamics play themselves out in daily lives and particular contexts. Looking at both humans and animals in and out of place extends the lens with which we consider how essentialized human spaces (e.g. urban settlements) and animal spaces (e.g. national parks) create conceptual and physical boundaries that are transgressed by numerous species, both human and nonhuman. Human ideas about animals are produced and reproduced through voluntary encounters, such as those experienced by tourists within Chobe Park, as well as through involuntary encounters, such as those experienced by Kasane shoppers surprised by warthogs. Human choice and control of animal-based encounters necessarily shape whether these are positive or negative, as premised upon notions of who belongs and does not belong in a particular place. Recognizing that space, and indeed context, matter in terms of resulting ideas (about animals) and actions that occur (towards animals) provides us with insights into how particular space-based scenarios and placements may generate particular human-animal encounters. We can use such insights to think further about (un)intended outcomes of spatial planning arising from human realms that create such spatial arrangements in the first place and shape human-animal relations as a result.

We would like to thank all those who participated in the research and those who provided in-kind assistance, including the Department of Environmental Science at the University of Botswana, staff at the Department of Wildlife and National Parks, and officials at the Ministry of Environment, Wildlife, and Tourism. Thank you to René Véron, Anne Milne, and David Burnes for their insights and support. Funding was generously provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Photo and Map Credits

Figure 1: Map of Botswana adapted from the Botswana Tourism Board “Botswana Tourism”; The World Bank Group.

Figure 2: Map of National Parks, Game Reserves and WMAs, CSO, “Wildlife Statistics.”

Figure 3: Map of Kasane, Chobe National Park and surrounding areas, CSO, “Wildlife Statistics.”

Figure 4: Giraffe in Tall Grass. Photograph by Aneta Karnecka. National Geographic: Photo of the Day. National Geographic, 15 Feb. 2010. Web. 30 Nov. 2010. <http://photography.nationalgeographic.com/photography/photo-of-the-day/giraffe-tall-grass/#caption>.

Figure 5: Black-maned Kalahari Lion. Photograph by June Liversedge. Roar: Lions of the Kalahari. National Geographic. Web. 30 Nov. 2010. <http://www.nationalgeographic.com/roar/photogallery/photo2.html>.

Figure 6: Elephants and vehicle in Chobe National Park, Botswana. Photograph by Andrea K. Bolla. 2008.

Figure 7: Elephant Billboard at the Kasane Entrance, Botswana. Photograph by Abdrea K. Bolla. 2010.

Notes

1. Exceptions in geography include Hovorka, “Transspecies Theory”; Whatmore and Thorne, “Elephants on the move”; Whatmore and Thorne, “Wild(er)ness.”

2. On Australian possums, see Power; on Singaporean monkeys, see Yeo and Neo; on chickens in Gaborone, see Hovorka, “Transspecies Urban Theory”; on urban cattle, see Philo; on Los Angeles animals, see Wolch, Brownlow and Lassiter.

4. See Orlikowski and Baroudi; Walsham.

6. See Department of Town and Regional Planning; Joyce.

7. See Gullo, Lassiter, and Wolc.

8. See Hoggart, Lees, and Davies.

12. See Mbaiwa, Parry, and Campbell; Twyman, “Livelihood Opportunity”; Twyman, “Natural Resource Use.”

16. See Arntzen, “Main Findings.”

19. See Arntzen, “Economic View on Wildlife.”

22. See Carlsson; Hemson; Mbaiwa; Verlinden; Verlinden, et al.

Works Cited

Adams, Jonathan S., and Thomas O. McShane. The Myth of Wild Africa: Conservation without Illusion. Berkeley: U of California P, 1992.

Adams, William M. Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in the Third World. Second ed. London: Routledge, 2001.

Arntzen, Jaap W. “An economic view on wildlife management areas in Botswana.” CBNRM Support Programme Occasional Paper (No. 10). Gaborone: Printing and Publishing Company Botswana, 2003.

Arntzen, Jaap W., D.L. Molokomme, E.M. Terry, N. Moleele, O. Tshosa, and D. Mazambani. “Main Findings of the Review of Community-Based Natural Resource Management Projects in Botswana.” CBNRM Support Programme Paper, IUCN/SNV and CAR, 2003.

Atlhopeng, Julius, Chadzimula Molebatsi, Elisha Toteng, and Otlogetswe Totolo. Environmental Issues in Botswana – A Handbook. Gaborone: Light Books, 1998.

Berg, Bruce L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2001.

Blaikie, Piers. “Is Small Really Beautiful? Community-Based Natural Resource Management in Malawi and Botswana.” World Development 34.11 (2006): 1942-1957.

Bolaane, Maitseo. “Chiefs, Hunters and Adventurers: The Foundation of the Okavango/Moremi National Park, Botswana.” Journal of Historical Geography 31.2 (2005): 241-259.

Boggs, L. “Community Power, Participation, Conflict and Development Choice: Community Wildlife Conservation in the Okavango Region of Northern Botswana.” Evaluating Eden Series Discussion Paper No. 17. IIED. International Institute for Environment and Development, London, 2000.

Botswana Tourism Board. “Botswana’s Tourism Industry.” Bajanala n.d.

Botswana Tourism Board.“Botswana Tourism Board.” Botswana Tourism Board 11 July 2010. <http://www.botswanatourism.co.bw/>.

Botswana Tourism Board.Travel Companion: Northern Botswana. Gaborone: Botswana Tourism Board, 2008.

Carlsson, Karin. Mammal communities in the southern Kalahari: Differences between land use types and seasons. MSc Thesis. Uppsala University, 2005. Cheetah Conservation Botswana. “Cheetah Conservation Botswana.” Cheetah Conservation Botswana 20 June 2010. <http:// www.cheetahbotswana.com>.

Cullis, Adrian, and Cathy Watson. “Winners and Losers: Privatising the Commons in Botswana.” Securing the Commons Series No. 9. IIED. International Institute for Environment and Development, London, 2005.

Department of Town and Regional Planning. National Settlement Policy. Gaborone: Government Printer, 1998.

Geertz, Clifford. “Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture.” The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. Ed. Clifford Geertz. New York: Basic Books, 1973. 3-30.

Gullo, Andrea, Unna Lassiter, and Jennifer Wolch. “The Cougar’s Tale.” Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature-Culture Borderlands. Eds. Jennifer Wolch and Jody Emel. London: Verso, 1998. 139-161.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Ed. Donna J. Haraway. New York: Routledge, 1991. 183-201.

Hemson, Graham. The Ecology and Conservation of Lions: Human-Wildlife Conflict in Semi-Arid Botswana. Diss. University of Oxford, 2003.

Hoggart, Keith, Loretta Lees, and Anna Davies. Researching Human Geography. New York: Oxford UP, 2002.

Hovorka, Alice. “Entrepreneurial Opportunities in Botswana: (Re)shaping Urban Agriculture Discourse.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 22.3 (2004): 367-388.

Hovorka, Alice.“Transspecies Urban Theory: Chickens in an African City.” Cultural Geographies 15.1 (2008): 95-117.

Joyce, Peter. This is Botswana. London: New Holland, 2005.

Lefebvre, Henri. Space. Trans. Donald Nicholson. Oxford: Blackwell, 1984.

Mbaiwa, Joseph E. “Wildlife Resource Utilization at Moremi Game Reserve and Khwai Community Area in the Okavango Delta, Botswana.” Journal of Environmental Management 77.1 (2005): 144-156.

McNeely, Jeffrey A., and Kenton R. Miller. “National Parks, Conservation and Development.” Proceedings of the World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1982.

Ministry of Finance and Development Planning. National Development Plan 9. Gaborone: Government Printer, 2003.

Mokolodi Nature Reserve. “Mokolodi Nature Reserve.” Mokolodi Nature Reserve 10 September 2008. <http://www.mokolodi.com>.

Orlikowski, Wanda, and Jack Baroudi. “Studying Information Technology in Organizations: Research Approaches and Assumptions.” Information Systems Research 2.1 (1991): 1–28.

Parry, David, and Bruce Campbell. “Attitudes of Rural Communities to Animal Wildlife and its Utilization in Chobe Enclave and Mababe Depression, Botswana.” Environmental Conservation 19.3 (1992): 245-252.

Philo, Chris. “Animals, Geography, and the City: Notes on Inclusions and Exclusions.” Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature-Culture Borderlands. Ed. Jennifer Wolch and Jody Emel. London: Verso, 1998. 51-71.

Philo, Chris, and Chris Wilbert. “Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: An Introduction.” Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations. Ed. Chris Philo and Chris Wilbert. New York: Routledge, 2000. 1-34.

Philo, Chris, and Jennifer Wolch. “Through the Geographical Looking Glass, Space, Place, and Society-Animal Relations.” Society and Animals 6.2 (1998): 103-118.

Phuthego, T.C., and R. Chanda. “Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Community-Based Natural Resource Management: Lessons from a Botswana Wildlife Management Area.” Applied Geography 24 (2004): 57-76.

Power, Emma R. “Border-processes and homemaking: encounters with possums in suburban Australian homes.” Cultural Geographies 16 (2009): 29-54.

Republic of Botswana. Botswana Demographic Survey. Gaborone: Central Statistics Office, 2009.

Republic of Botswana.Chobe District Development Plan 6: 2003-2009. Gaborone: Government Printer, 2003.

Republic of Botswana. Central Statistics Office. Population and Housing Census. 28 September 2008 <http://www.cos.gov.bw>.

Republic of Botswana.Botswana Environment Statistics. Gaborone: Central Statistics Office, 2008.

Republic of Botswana.Wildlife Statistics 2004. Gaborone: Central Statistics Office, 2005.

Schiess-Meier, Monika, Sandra Ramsauer, Tefo Gabanapelo, and Barbara Konig. “Livestock Predation—Insights from Problem Animal Control Registers in Botswana.” Journal of Wildlife Management 71.4 (2007): 1267-1274.

Twyman, Chasca. “Livelihood Opportunity and Diversity in Kalahari Wildlife Management Areas, Botswana: Rethinking Community Resource Management.” Journal of Southern African Studies 26.4 (2000): 783-806.

Twyman, Chasca.“Natural Resource Use and Livelihoods in Botswana’s Wildlife Management Areas.” Applied Geography 21.1 (2001): 45-68.

United Nations Environmental Programme—World Conservation Monitoring Programme. “World Database on Protected Areas.” United Nations Environmental Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Programme 1 November 2007. <http://sea.unep-wcmc.org/wdpa/>.

Verlinden, Alex. “Human Settlements and Wildlife Distribution in the Southern Kalahari of Botswana.” Biological Conservation 82.2 (1997): 129-136.

Verlinden, Alex, Jeremy S. Perkins, Mark Murray, and Gaseitsiwe Masunga. “How are People Affecting the Distribution of Less Migratory Wildlife in the Southern Kalahari of Botswana? A Spatial Analysis.” Journal of Arid Environments 38.1 (1998): 129-141.

Walsham, Geoff. Interpreting Information Systems in Organizations. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, 1993.

Whatmore, Sarah, and Lorraine Thorne. “Elephants on the Move: Spatial Formations of Wildlife Exchange.” Environmental Planning D: Society and Space 18.2 (2000): 185-203.

Whatmore, Sarah, and Lorraine Thorne. “Wild(er)ness: Reconfiguring the Geographies of Wildlife.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 23 (1998): 435-454.

Willis, Jerry W. Foundations of Qualitative Research: Interpretive and Critical Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2007.

Wolch, Jennifer R. “anima urbis.” Progress in Human Geography 26.6 (2002): 721-742.

Wolch, Jennifer R., Kathleen West, and Thomas E. Gaines. “Transspecies Urban Theory.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 13.6 (1995): 735-760.

Wolch, Jennifer, Alec Brownlow, and Unna Lassiter. “Constructing the Animal Worlds of Inner-City Los Angeles.” Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations. Ed. Chris Philo and Chris Wilbert. New York: Routledge, 2000. 71-97.

Wolch, Jennifer, and Jody Emel. “Witnessing the animal moment.” Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature-Culture Borderlands. Ed. Jennifer Wolch and Jody Emel. London: Verso, 1998. xi-26.

World Travel and Tourism Council. “WTTC Highlights Botswana travel & tourism potential.” World Travel and Tourism Council 3 January 2009. <http://www.wttc.org/>.

Yeo, Jun-Han, and Harvey Neo. “Monkey business: human-animal conflicts in urban Singapore.” Social & Cultural Geographies 11.7 (2010): 681-699.