Meadowarts’ House of Beasts

Reimagining Human & Non-human Animal Relations at Attingham1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.10036

Joanna Latimer is Professor of Sociology at Cardiff University School of Social Science and the ESRC Centre for the Social and Economic Aspects of Genomics (Cesagen). She has published widely on medicine, science, the body and culture, and contributed to publications at the cutting edge of social theory, including on the art of dwelling (Space and Culture) and a special issue of The Sociological Reviewentitled “The Politics of Imagination.” Her books include Un/knowing Bodies(Wiley-Blackwell) and The Gene, The Clinic and The Family: Diagnosing Dysmorphology, Reviving Medical Dominance (Routledge) is in press. She is editor of the Sociology of Health and Illness, and is in process of editing a special issue of Theory, Culture and Society on relationalities amongst different kinds. She is currently immersed in an ethnography of ageing and biology.

Email: joanna.latimer@york.ac.uk

Humanimalia 4.1 (Fall 2012)

Introduction

The exhibition House of Beasts plays into and out of the history of people’s relationships with other animals, most particularly as they are represented by the National Trusts preservation of Attingham as an 18th/19th century dwelling. Like the building and the landscaping the exhibition helps us to see the collection at Attingham as important tools for displays of identity, particularly in terms of prestige and status, and for the enactment of both gender and class relations. But the exhibition does more than this: it helps unconceal some of the more invisible and implicit values and meanings that these human-animal relations embody. It draws our attention to how particular human-animal relations are also central to the celebration of human endeavor and to the emergence of new spheres of social, economic, and cultural life, such as science, industry, landscape architecture, technology and agriculture. In this paper I examine how some of these exhibits work through provocation to disrupt the orderings through which the National Trust’s display of Attingham as a particular world, a way of life, is presented. I suggest that we can think about what is being kept and cherished, cared for and nurtured, through how human-animal relations are dis-ordered by the exhibition. I suggest that it poses serious questions about human endeavor, and the problems of celebrating the human enhancement of Nature that occurs in the process of building without thinking, of industry and endeavor without care.

Let us now travel to Attingham and explore the kinds of human-animal relations that we can see there — the house and its collections, its landscape and its grandeur — through the eyes of the exhibition.

Animals all about us

As the Trust represents it, Attingham is usually seen as one of “Britain's greatest contributions to Western art: the country house, together with its collections and landscape setting” (The Attingham Trust).

Anne de Charmant, the curator of the exhibition, stated during her public tour of the exhibition that we are used to seeing animals in sites like Attingham in terms of decoration or emblems. The walls are adorned with paintings of elegant well-bred horses and dogs, hunting scenes, and picturesque landscapes, more animals are incorporated in wallpaper and ornaments. Animals may be there in scientific collections — cabinets of insects carefully categorized, glass domes and cabinets of curiosities displaying exotic creatures, witnesses to human travel and the expansion of knowledge. Outside, deer and exotic cattle decorate the parkland, while swans glide up and down the an elegant and picturesque turn of the river Tern, the backdrop to the giant Cedars of Lebanon, which, like the vast scale of the neo-classical front of the house itself, testify to the grandeur and magnificence of the Berwick family within, and of the architects, builders, gardeners, and landscapist, Humphrey Repton. Animals are also often present in coats of arms and other emblems of genealogy and heritage. As de Charmant noted in her presentation of the exhibition, recognizing and being able to interpret the mythic and other references in the use of animals as symbols in the decoration at Attingham was all a part of displaying social status and position in the 18th century. It was one form of showing that you were educated enough to be in the know.

Within this perspective Attingham is then a celebration of a way of life at the turn of 17th & 18th centuries: civilized, reasonable, elegant, and picturesque, in gentle pursuit of knowledge and progress. There are few intrusions of the passions of the romantic, or the mess and muddiness of the everyday life of humans and animals. There are no manure piles steaming in the stable yard, no servants cleaning the dog hairs off the carpets, no wigs being disinfested of fleas. In addition, the life of Attingham is presented as a holistic one that is ordered and orderly, in which the human is in harmony with Nature, and in which humans and animals are in their place.

The collection, the landscape, and its representations by the NT represent a way of life intimately rooted in man’s relation to nature, particularly in relations with the animal and with other animals. We feel Attingham is a dwelling with beasts within and without: a way of life in which nature and the social, human and the animal, are in intimate and orderly proximity. Our visits and walks there help us to be included momentarily in this intimacy and this orderliness. We get a sense of how Attingham would have been buzzing with the activities surrounding the estate’s role as a center for farming and the production of food, for sport, as well as a site where birds, bees, and other wild creatures thrived.

House of Beasts helps us to see how animals are all about us at Attingham. But the exhibition also helps us to see that the Attingham estate is a celebration of a form of social life on the verge of a proliferating division of labor through spheres of human endeavor that will become more and more specialized, and separated off. The production of food will become separated off from the everyday life of its consumption, and the science of farming will be undertaken far from the operations of the farm itself. The exhibition also draws our attention to, and provokes reflection on, how the form of civilization captured at Attingham rests upon the ordering of relations between human and animal.

This separation is evident not just in the division between his and hers wings, or upstairs and downstairs, or the outside and the inside, although these are important. Rather, the exhibition makes visible all the work that goes into creating a world through keeping certain things apart to maintain a particular kind of order.

A dwelling of distinction(s)

So how does the exhibition help us to see Attingham not just as a dwelling of distinction, but also as a dwelling of distinctions? I suggest that it does this through provoking moments of disconcertment. Verran explores how bodily disconcertment may be understood as an expression of discomfort that we experience when there is a disordering of the taken-for-granted underpinnings, or conditions of possibility, of how we think the world. For example, at the opening of House of Beasts I overheard one of two elderly women standing in front of one exhibit exclaim, “Oh I don’t like that! That’s not what I call art. It’s horrible.” She turned away from the exhibit to the others present, pressing them into siding with her, but then was drawn back. She didn’t walk away, but tried to make sense of it; physically she was rooted to the spot, fascinated. Something about the exhibit upset the world as she usually thought it; and because of this, because it confounded the usual ways in which things are ordered, it was, like dirt, good to think2 — and talk — about!

Our first moment of disconcertment comes when we enter the stables. Instead of traces to remind us of horses snorting and shuffling in the stalls, with a pungent smell of horse bodies and hay, we come upon a film in which horses are occupying one of the most sacred of human spaces, a cathedral. They are there for the night, filmed secretly in their private and mysterious horse world, free to roam as if they are outside, grazing the floor, spooking at invisible fears, trotting around the knave and up the steps.

Kathleen Herbert, Stable

(Reprinted with kind permission of Meadowarts)

We hear their hoofs on the beautiful old stone and their breath, as they snort, disrupting the intense silence. We feel their otherness, and their strange freedom to occupy and disorder our world. This is what so astonishes — how the horses, in a strange inversion of the usual ordering of human-animal relations, appropriate the Cathedral to make themselves at home. The juxtaposition and inversion of the usual order of things — the horses in the cathedral rather than in the fields or stables — reminds us not just of all the horses’ otherness but the work and the gift-giving that goes into their becoming a part of our world, of their becoming human.

As we move into the house there are more surprises. Many paintings in the house celebrate hunting — fox hunting, deer stalking, and hare coursing. But as we travel with House of Beasts down into the Housekeeper’s room we come across a tiny fox curled and nestled into an armchair, where we should find perhaps a cat or a small dog. And as you can see in the photograph of “Refuge,” the chair is itself in a state of collapse, the distortion intensifying the disconcertment to come with the glimpse of the fox curled into its fold.

Nina Saunders, Refuge

(Reprinted with kind permission of Meadowarts)

“Refuge” is thus a surprise, because, as anthropologist Mary Douglas suggests, the fox is “out of place.” In the usual ways of creating order at Attingham, the fox should be in the woods and parkland ready to be chased by the hounds. We know now that foxes can be kept as pets just like dogs. But for those dwelling at Attingham, the fox would never have been thought of in that way. The irony then is in the idea that such a house should give refuge to a creature usually figured as good for sport and a wily adversary.

As we enter the kitchen we are still in the downstairs of the house, and we are in for another surprise. Where there should be reminders of meat roasting over the fire, bread being kneaded and vegetables chopped on the worn and scrubbed surface of the kitchen table, game hanging in the game cupboard, all that wonderful Downton Abbey warmth and order, we are confronted with the luxuriousness and rich decorative beauty of game-bird feathers flowing in an exquisite river from one of the shining copper pots on the stove, like the magnificent and exotic tail of a peacock

Kate MccGuire, Evacuate

(Reprinted with kind permission of Meadowarts)

This beauty should be captured upstairs, in a still life with pheasant as a celebration of a particular kind of cultivated life. Or we should come across the birds as we stroll outside, as the pheasants that strut and peck in the woodlands, a feature of the managed estate, husbanded to be ready for the shooting season.

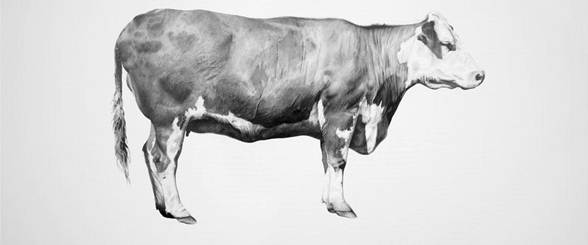

Upstairs there are more surprises: clever inversions and transgressions of the usual order of things. Amongst the portraits of prized animals, instead of a portrait of a prized bull or valued racehorse hanging over the mantelpiece, we find the portrait of the mundane, a dairy cow, “Buttercup.”

Robert Davies, Buttercup

(Reprinted with kind permission of Meadowarts)

In the exquisite civilization of the library, with its books, ornaments, fireside, and comfortable chairs, where most aspects of human animality are erased, we encounter a herd of deer crashing through the door.

Susie MacMurray, Herd

(Reprinted with kind permission of Meadowarts)

The outside crashes into the inside, disturbing the peace; power is inverted and given to the deer, customarily represented in the picturesque of the Age of Reason as, in their relations with the human, the most timid of creatures.

It is not simply a matter of valuing some animals over others by acknowledging them as companions. For example, as we walk our dogs along the pathways, we come across the sculpture of a dog made of all the comfortable clothes that the dog’s human family wears to take it on a walk – old socks, scarves, and so forth.

Des Hughes, Do You think of me often?

(Reprinted with kind permission of Meadowarts)

There are three important twists to this dog sculpture that provoke reflection. First, the dog is faceless; second, the comfortable clothes have been turned into a rusty chain mail, something that does not just protect the dog, but encases it; and third, the dog's posture. It sits like many dogs do when they have got something they are proud of, its paw resting on some doggy trophy, in triumph, but also in a kind of proud challenge. When we look closely the paw is resting not on a bone freshly redug from the garden, or even the carcass of a rotting and mouldy rabbit, but a human hand. The dog that bites (off) the hand that feeds it. Reminiscent of the film in the stables, Des Hughes’s sculpture reminds us of all that the animals that we domesticate or make our companions do to gift us their closeness. I want to thus to suggest that the exhibition helps us to see, momentarily, how non-human animals have to ‘become’ human if they are to be included in the domestic fold as companions.

However, in the exhibition it is not only the animals that break free of where they are usually placed by the humans; in House of Beasts the humans themselves morph into animals.

Marcus Coates, Red fox

(Reprinted with kind permission of Meadowarts)

In one of the corridors, a picture of a man-fox, blurred and red in a distant field at twilight — at first we think it is a fox, and only after a careful look down we realize that it is a man. A reminder for a moment of the animality in us, and all that we do to become the kind of human suggested by the order and civilization of Attingham.

By displacing, blurring and transgressing the usual distinctions that underpin how the life represented at Attingham is ordered, these witty and clever exhibits disconcert. They help us to rethink the human-animal relations, the divisions and the distinctions that a way of life rests upon and provoke us to think about our own life with animals as well those in the past. Becoming aware of these relations, particularly those that are the most taken for granted, is always a surprise.

Human endeavor: building without thinking

I want to now stress that the exhibits make incursions into the House and the parkland. These incursions bring into view the house as a representation of the emergence of modern forms of life, and the creation of a world that celebrates human endeavor. But in the form of civilization that we find at Attingham human endeavor is to some extent tempered by its connections to the nature that it enhances. Specifically, while the exhibition helps us to see the relationship between the House and the beginnings of new spheres of social, economic and cultural life — namely science, industry, landscape architecture, technology, and agriculture —, these spheres are still present and embedded in the everyday life of the Park, and in everyday human-animal relations, however ordered, they are yet to become separated off into the distant domains of industrial agriculture or laboratory science.

We experience the exhibits as gentle and strange transgressions, moments of disorder that provoke our reflection on the connections and disconnections, distinctions and divisions, that Attingham relied upon to create a particular kind of dwelling. But it is also a monument to a way of building that is deeply connected to creating a life. In particular, our own animality is not made absent, but is represented in terms of its cultivation through human endeavor: the animals are represented as cultivated, bred, discovered, placed. The way of life organized around them that is celebrated by the art, in both the pictures and the landscaping, celebrates human endeavor. When in the right place, the pheasants and the deer are ornamental, they help make up the picturesque; but when the feathers and the antlers intrude presence into the civilization of the house, as in the exhibits “Herd” and “Evacuate,” they remind us that in this world they can only be picturesque where they are in place, ordered, and managed: deer need to be culled, pheasants need to be raised, bred, shot and eaten.

The difference between building and producing in a dwelling such as Attingham Park is that the everyday workings of these spheres of life are visible, including the connections as well as the divisions and distinctions between humans and animals and between different kinds of animals. The work, the order, and the human endeavor can be seen as resting on keeping animals and humans in their places. The venison at the table were once the elegant deer adorning the park, the prize bull pictured in a portrait in the sitting room was once grazing the fields at the center of a herd of cattle, slaughtered and eaten when needed. These relations are transparent in the life at Attingham, whereas increasingly how these relations work in terms of our own life have become hardly visible to us, except as consumers or on reality TV.

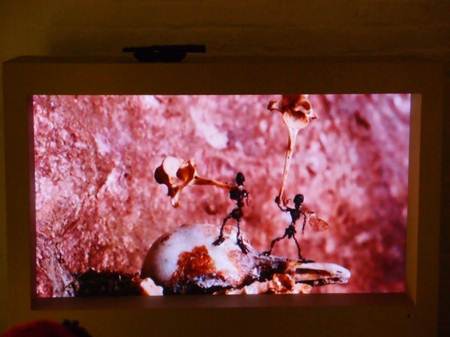

Tessa Farmer’s work offers us as an allegory of what happens when human endeavor — building — happens without thinking, when we make a place in which we cannot dwell. Tessa Farmer’s & Sean Daniel’s video installation, “Den of Iniquity,” in the silver vaults in the basement of the Attingham House offers us a vision of ourselves and of our relations to animals and to nature.

“Den of Iniquity” is a short video revealing the industrious activities of what the artist calls her fairy species. All the elements of the video — the fairies and the other creatures depicted — are made up of bits and pieces of debris and dead insects the artist has collected. The video shows the fairies dragging their latest prey, the carcass of a dead rat — back to their home, where they string it up by its feet, like any other dead carcass in an abattoir or game cupboard. The video shows the fairies’ different technologies and industries. For example, there is a honeycomb with bees trying to escape from their cells, and birds on nests laying eggs that roll down a fairy-made chute.

The Fairies’ egg laying machine

(Reproduced with kind permission of Tessa Farmer)

The fairies have weapons and tools made out of bones. For example, one fairy hammers a pin through a moth carcass using a tiny bone. Moths and butterflies are pinned to walls by the fairies for decoration. But later in the video we see the butterflies and moths pinned to the walls still flapping their wings. In this the video helps evoke an image of real cruelty.

A fairy pinning the moth to the wall

(Reproduced with kind permission of Tessa Farmer)

The fairy bashing another fairy off the honeycomb

(Reproduced with kind permission of David Kipling)

At one moment a fairy hammering bees back into their honeycomb turns to its companion in wickedness and bashes him with his bone, knocking him off the precipice.

Beauty and color come from the moths and butterflies murderously pinned with their delicate wings flapping, from birds ingenuously imprisoned on their nests as egg producers by the ribcages of other creatures that the fairies have killed, from their delicate eggs and the soft green moss. The film provokes because it shows endeavor without reflection, building without thinking a place in which it is hard to dwell, to inhabit. As the film draws to a close the color is drained out. What we see in the little black, winged fairies is an image of human industry, invention, and productivity, where what gets made is a dry and desiccated world of bones, and sand, and dust. Beauty is entrapped in modes of production: what get created are the bare bones of existence — not a place to dwell.

The fairies are wicked but they are also “us” — we know this because of how they use their hands, because of how they chatter away and exclaim to each other as they go about their work, and because of their sheer inventiveness — they make pulleys and all sorts of other technologies to do their work. What we see in the fairy species is an image of one species killing, dominating, and capturing other species in the making up of their world. The video offers an allegory of human industry and endeavor, but of a kind in which it is other creatures — bees, birds, moths and butterflies — that are being subjected by the fairies in the building of their fairy world. Because what we see is the fairies exploiting, mastering, and subjecting nature to their will, endeavor here is pictured as what the philosopher Martin Heidegger calls building without thinking. Thinking for Heidegger is when we take care, and cherish, in our building, only then do we create a place to dwell:

the manner in which we humans are on the earth, is Buan, dwelling. This word bauen, however, also means at the same time to cherish, to protect, to preserve and to care for, to till the soil and cultivate the vine. Such building only takes care… Building as dwelling, that is, as being on the earth, however, remains for man’s everyday experience that which is from the outset “habitual” — we inhabit it …. (Heidegger 349)

The vision portrayed is of invention and technology harnessed to subsume nature to our will. There is no care or cherishing here. What the “Den of Iniquity” represents is human endeavor and enterprise building upon relations with animals and with nature untrammeled by care.

Making Room for Human-Animal Relations

The exhibition helps us to see complexity over the values being expressed at Attingham Park. This is not a matter of simplistic ideologies. The provocation of the exhibition — witty and troublesome — not only upsets the usual civilized divisions and modes of ordering through which animals, and the animal in us, is portrayed by the collection. We also see the stress on a civilization that enhances the world as it finds it; we see a world that celebrates the extension of human endeavor, but with attention to what it finds in the first place. This keeping as a form of care, a kind of latter day ecology, is evident in how the river, the hill, and the parkland come into a wonderful association through the placing of the bridge. As Martin Heidegger would suggest, there is a gathering: the locale comes into being where building creates a dwelling place through cherishing nature, not simply exploiting it. Is it this that we celebrate when we visit Parks such as Attingham?

The civilization being celebrated here keeps what is there in nature and builds on it, with harmony and balance. This of course requires knowledge. But at Attingham knowledge and science are represented as still in balance with nature. For example, in the portraits of the Berwick family’s racehorses and prize cattle we see the results of an emerging science of breeding as a science that is aimed at bringing out the best in nature rather than changing its fabric in a laboratory. In contrast, the exhibit by Hugo Wilson, entitled “Modern Farm Animals,” and consisting of a box set of etchings of genetically modified animals, provokes reflection on those aspects of the Attingham collection that celebrate the new sciences of breeding by getting us to think how far we have come from their balance. Or will we in years to come celebrate Dolly the sheep in the same way as the Berwick’s celebrated their prize herd of cattle and racehorses, as testimony to the triumph of human endeavor?

House of Beasts invites us to a dialogue with our relation to nature, and to the animal, in terms of how we can balance our industry and our will to knowledge and power so that we might keep that balance and harmony with the non-human world. We get a glimpse of a vision, in which we remember how the worlds we make are co-constructed through cherishing our relationalities: an ecology of relations in which building is done with thinking, to make a place to dwell rather than merely to exist.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank all at Meadowarts.

Notes

1. Presentation to the public symposium, “Enquiries into the Human and the Animal,” The Darwin Festival, Shropshire Wildlife Trust, Shrewsbury, 18th February 2012

2. “Lord Chesterfield defined dirt as matter out of place. This implies only two conditions, a set of ordered relations and contravention of that order. Thus the idea of dirt implies a structure of ideas. For us dirt is a kind of compendium category for all events which blur, smudge, contradict, or otherwise confuse classifications. The underlying feeling is that a system of values, habitually expressed in a given arrangement of things, has been violated.” (Douglas 338)

Works Cited

The Attingham Trust (2012) http://www.attinghamtrust.org/.

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. 1966.

Heidegger, Martin. “Building, dwelling, thinking,” in D. F. Krell, ed. Basic Writings. London: Routledge, 1978.

Verran, H. “Imagining Nature Politics in the Era of Australia's Emerging Market in Environmental Services Interventions.” Special Issue: “The Politics of Imagination.” J. Latimer & B. Skeggs, eds. The Sociological Review 59.3 (2011): 411–431.